February 3, 2018 marked 75 years since the conclusion of the Battle of Stalingrad. After almost six months of vicious street-to-street fighting, Stalingrad’s Soviet defenders repelled their German opponents—albeit at the cost of almost a million Soviet lives. The victory marked a significant turning point in World War II. After facing almost certain defeat before Stalingrad, the Soviets advanced (with a few setbacks) from Stalingrad all the way to Berlin.

Newspapers during the Battle of Stalingrad were filled with reports, poems, stories and photographs. The front page of 3 February 1943’s Pravda celebrates Stalin’s role in achieving victory (left) (from author's collection); and the Medal “For the Defense of Stalingrad,” awarded to all participants in the defense effort (right).

Stalingrad was hailed in February 3’s Pravda (Truth) newspaper as “the greatest battle in history” and “a catastrophe of titanic proportions” for the German invaders. These claims were more than propagandistic hyperbole.

For eyewitnesses like the writer Vasily Grossman, who spent several months at the Stalingrad front as a journalist, the victory was a testament to “the glory of our people, the glory of their bravery, patience, and their capacity for self-sacrifice.” Time and again, Soviet writers, filmmakers and ordinary citizens—especially those who had witnessed Stalingrad—celebrated the battle’s enormous cultural and historical significance.

Memory of the battle presented in hundreds of novels, memoirs, films, poems, and monuments, gave Soviet citizens a means to imagine their nation as the savior of European civilization against the genocidal German invaders.

The post-war reconstruction of the Soviet Union was closely linked to a rebirth of the nation that occurred at Stalingrad. The native Stalingrader, journalist and author Vasily Koroteev explained that after February 1943, “the entire Soviet nation rose up to resurrect Stalingrad from ashes and ruins” by rebuilding the city. Stalingrad was not just a strategic victory, nor was it defined solely by the staggering loss of huge numbers of troops and civilians in horrific fighting. Stalingrad was a resurrection: of the city itself, of national unity and spirit, and of hope for the future.

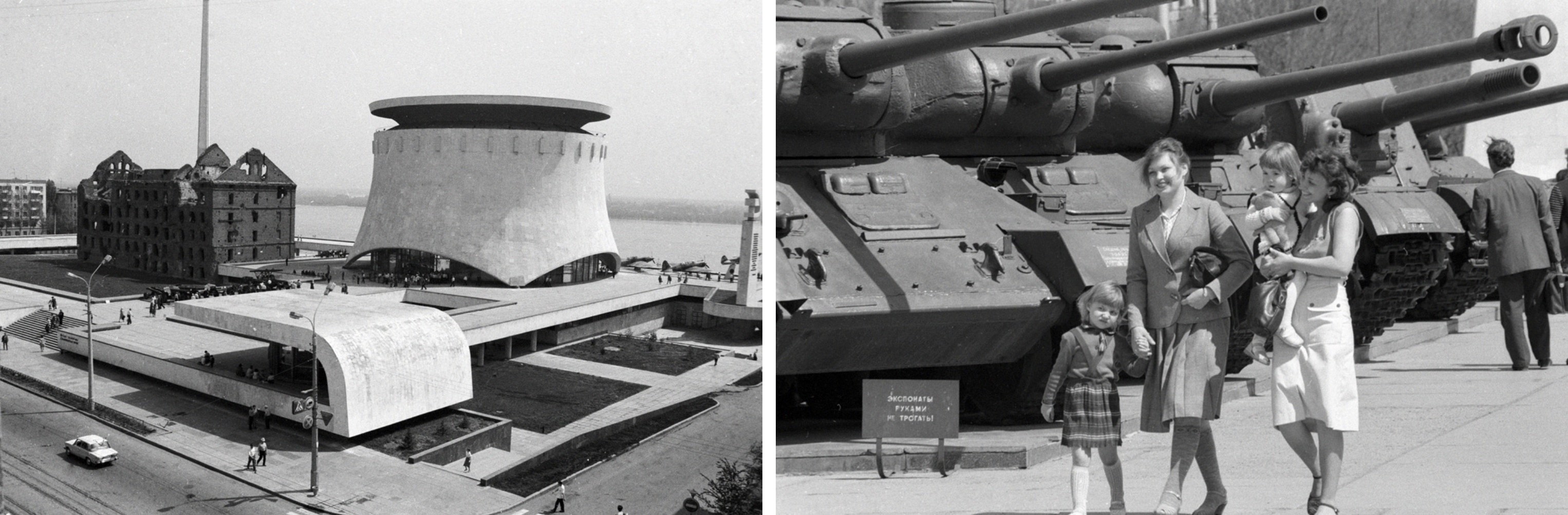

The building of the Memorial Museum-Panorama "The Battle of Stalingrad" in 1985 (left), and visitors passing by armored vehicles outside the museum (right).

In the twenty-first century, memory of the Second World War, and especially of Stalingrad, continues to exert a great hold over Russia’s population.

Russians’ interaction with this past is clearly evident in the city of Volgograd—the name given to Stalingrad after the collapse of the Soviet Union—where the memory of Stalingrad is inescapable. The 85-metre Soviet statue The Motherland Calls, sited on a hill that saw some of the fiercest fighting in 1942, towers over the city. The Pavlov House, a building held for several weeks by a handful of Soviet defenders under the command of the eponymous Lieutenant Pavlov, is partially preserved as one side of a 1950s residential building.

The Motherland Calls statue at the Mamayev Hill War Memorial in Volgograd (left), and veterans of the Great Patriotic War and their relatives visiting the memorial in 1983 (right).

Pavlov's House in 1943, following the Battle of Stalingrad (left), and the Pavlov House memorial today (right). The red-brick wall is what remains of the Pavlov House in downtown Volgograd. It is built into the side of a post-war residential building, occupied by ordinary Volgograders.

Volgograders—or Stalingraders, as many older residents still call themselves—go about their daily lives in a city that is equal parts 1950s Stalinist reconstruction, ruin, memorial complex, and post-Soviet steel and glass edifice.

Children examine a cannon in the square in front of the “Battle of Stalingrad” panoramic museum and a mill destroyed during the battle (left), and the Monument to Komsomol Defenders of Stalingrad (right).

Stalingrad’s influence in the present extends well beyond visible remnants of the battlefield and monuments to the fallen. Russians still use memory of the battle as a way to reimagine national and individual identities, just as Grossman and Koroteev had done in the Soviet period.

Whenever the battle is mentioned in popular culture, audiences flock to new films and books about Stalingrad. Usually, fierce debates break out around historical authenticity and the loss of Soviet power and morality during the 1990s. Fedor Bondarchuk’s 2013 film Stalingrad, for example, smashed box office records for a domestic production.

Russians’ desire to connect Stalingrad’s status as a moment of historical resurrection with the creation of new life today is widely expressed in a desire literally to relive the past.

In dozens of pulpy science fiction and alternative history novels churned out by major Moscow publishers, unremarkable characters from the 21st century travel through time to fight at Stalingrad or Soviet soldiers visit the future to fight off German or Western “aliens” at Stalingrad (sadly, none of these works exist in English translation). These characters are able to become heroic in a way impossible in the present by “winning” at Stalingrad all over again.

The front cover of Yury Stukalin and Mikhail Parfenov's 2013 novel Snipers from Space: 22nd Century Stalingrad depicts a Soviet soldier who has travelled from the Stalingrad of 1942 to the future to defend the Earth from a genocidal alien regime (left), and an advertisement for Fedor Bondarchuk’s 2013 film, Stalingrad (right).

Russians see the sacrifices made at Stalingrad—or in a “new Stalingrad,” as the 2014 battle for Donetsk airport in Ukraine was termed online and in nationalist media—as a way to reinvigorate the future.

Thus when we look to the extensive 75th anniversary celebrations planned by the Putin government for 2018, we can see the deeper cultural meaning of what could otherwise be interpreted as a series of soulless rituals laid on by out-of-touch bureaucrats and politicians. Memorial exhibits in museums in Moscow and Volgograd, parades, extensive coverage in mass media, wreath laying, veterans’ visits to schools, concerts, educational programs at universities—even an all-Moscow school sports tournament and a senior-youth chess tournament—are a reminder of the continuing importance of history in daily life.

One school principal’s claim that the anniversary would be the “highlight of the school year” at a school in Kamyshin, a small town a few kilometers from Volgograd, is not jingoistic hubris. It was fed by the certainty that, as the principal explained, “the [battle’s] heroes are alive so long as we remember them.”

By remembering Stalingrad through the extensive array of events planned by the state and by citizens, or by visiting physical memorials, Russians are reminded that, just as at Stalingrad in 1942, improbable victories and national utopias might occur at any moment in the near future thanks to acts of patriotic remembrance.

Read more on Stalingrad:

Vasily Grossman, Life and Fate, trans. Robert Chandler (London: Vintage, 2017)

Vasily Koroteev, Komsomol’tsy Stalingrada / The Komsomol of Stalingrad (Moscow: Molodaia gvardiia, 1949, in Russian)

Konstantin Simonov, Days and Nights: A Novel, trans. J. Fineberg (London: Hutchinson, 1953)

Yury Stukalin and Mikhail Parfenov, Zvezdnye snaipery: Stalingrad XXII veka / Snipers from Space: 22nd Century Stalingrad (Moscow: Eksmo, 2013, in Russian)