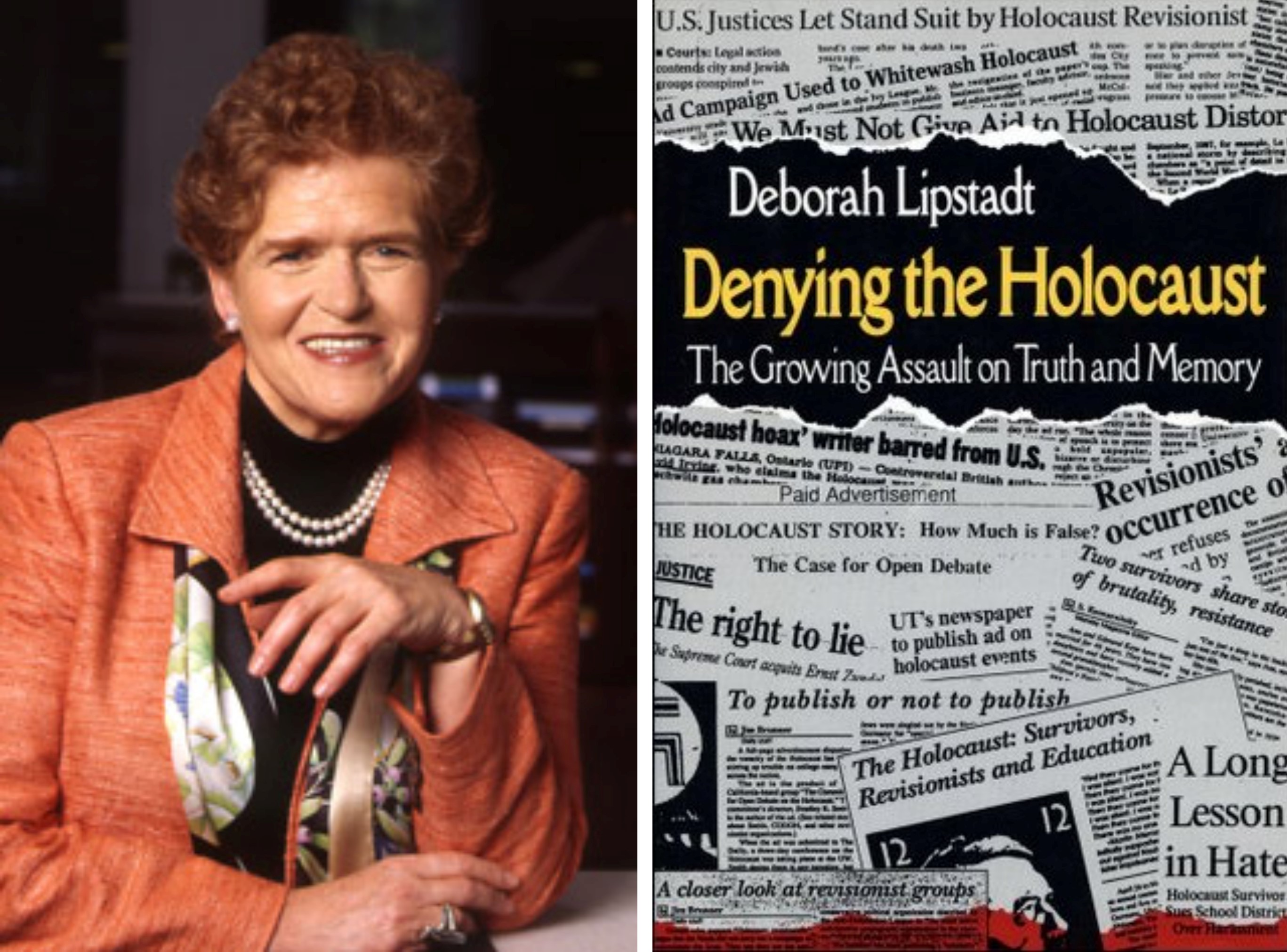

Historian Deborah Lipstadt begins her 1994 book, Denying the Holocaust: The Growing Assault on Truth and Memory with a methodological chapter she entitles, “Canaries in the Mine: Holocaust Denial and the Limited Power of Reason.” She worries about the 20% of Americans who, when surveyed about whether the Holocaust happened, answer in the negative.

I might rather emphasize the full third of Americans who deny the scientific validity of the theory of evolution as an earlier canary also on life support, but her point is well-taken: the dwindling importance of facts and learning in anti-intellectual American culture is reaching a critical mass from which we might not be able to return.

As I write in mid-November 2016, slightly less than half of Americans who voted in the national election selected Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton, a deliberate choice eschewing policy proposals based on data in lieu of a populist social media demagogue who speaks in simplistic, abusive platitudes.

In her chapter, Lipstadt places part of the blame for the rise of Holocaust denial on relativist postmodern philosophy of the sort espoused by Richard Rorty. The maneuver is a common one from the perspective of positivism. In The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark (1995), Carl Sagan similarly dismisses the post-modernists as irrationalists who reject the rightness of scientific understandings of the world.

Lipstadt is a more sophisticated thinker than Sagan, at least worrying about the limitations of positivism. She begins the chapter with a pessimistic epigram from German classicist Theodor Mommsen: “You are mistaken if you believe that anything at all can be achieved by reason. In years past I thought so myself and kept protesting against the monstrous infamy that is antisemitism. But it is useless, completely useless.” However, Lipstadt stops short of rejecting the positivism deeply defended by academic historians.

Deborah Lipstadt (left), and her 1994 book Denying the Holocaust: The Growing Assault on Truth and Memory (right).

I find this lamentable, because Lipstadt comes very close to finding the middle-ground solution between rightfully critiquing an anti-intellectual culture that devalues facts, but at the same time acknowledging that our access to such facts is woefully crippled by ideological filters far beyond our ability to identify and control against.

Such a position is readily available. Sociologist John Wilson labels such as third intellectual space (between positivism and relativism) as historical realism or materialism. In this theoretical position, our access to the truth of the external world is not easily provided (as in positivism), but nor is it meaningless (as in relativism). Instead, in the realist position, our access to truth is forever shrouded by ideological filters, such that the best we can do is build rhetorical arguments that overlap with one another to give us a reliable sense of what is and is not close to the truth.

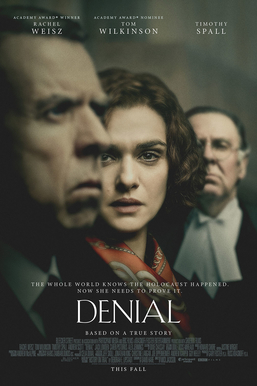

I build critical realism as a position pointed toward but not embraced by Lipstadt’s book because it seems a productive way of understanding the new fiction film, Denial (2016), Mick Jackson’s adaptation of her later book, History on Trial: My Day in Court with a Holocaust Denier (2005).

British Holocaust denier David Irving, 2003.

On the one hand, the film is a standard courtroom melodrama about the charge of libel brought against Lipstadt by a British Holocaust denier, David Irving. As a melodrama, the film utterly fails to address the complex theoretical crisis engaged by the opening chapter of Denying the Holocaust.

Instead, this generic tradition enforces the most simplistic forms of positivism. Lipstadt is clearly correct, and Irving is clearly a racist, so that when she rightfully wins at the end, she and her lawyers celebrate the triumph of reason. When her lawyer, Richard Rampton (Tom Wilkinson) refuses to shake the congratulatory hand of David Irving (Timothy Spall), we are meant to thrill with the righteousness of it all. However, when the triumphant Donald Trump visited Barack Obama in the White House after the election, shaking the recent winner’s hand was the only option for a sitting President interested in defending the future functioning of the government. In the real world, Hollywood gestures of moral purity are most often not available.

And yet, Denial is a terrific film. When read outside of the genre of the courtroom melodrama, the film represents the best of what we have available to us to represent the historical past. Filmmakers can put before us the most engaging artistic manifestations of the frailties of human behavior, knowing they cannot carry the burden of the “Truth,” but nonetheless contribute to an overall flux of understanding that leads us toward the truth.

Rachel Weisz as Deborah Lipstadt in a scene from the movie Denial, 2016.

The career of Mick Jackson has led him in this direction. He began by directing episodes of James Burke’s Connections (1978), one of the great television science documentaries that eschewed positivism for critical realism. Burke would take his viewers on wild flights of fancy, pushing at connections between scientific discoveries and larger social and cultural developments.

Afterwards, Jackson became a Hollywood fiction filmmaker, but one equally devoted to the pressuring of classical storytelling toward complex understandings of the world. In L.A. Story (1991), he critiques the superficial nature of Los Angeles by invoking a wide array of works by William Shakespeare, from Hamlet to The Tempest.

Timothy Spall as David Irving in Denial, 2016.

The casting of Denial furthers its complexity of characterization. Deborah Lipstadt is not just an overly aggressive, lonely academic who must learn the importance of teamwork, she is rendered more complex by the casting of Rachel Weisz. Much like her role as Hypatia in Spanish director Alejandro Amenabar’s Agora (2009), Weisz again plays a powerful woman at the center of defending the truth from abusive forces (in Agora, protecting ancient mathematics and reason from the Christianizing Roman Empire).

Jackson surrounds Weisz with a gallery of great British character actors. Timothy Spall, one of the primary villains of the Harry Potter films, plays Irving with appropriate unctuous menace. Andrew Scott and Mark Gatiss, both prominent actors in the Sherlock BBC juggernaut play members of Lipstadt’s defense team, often at odds with her arrogant belief she always knows best.

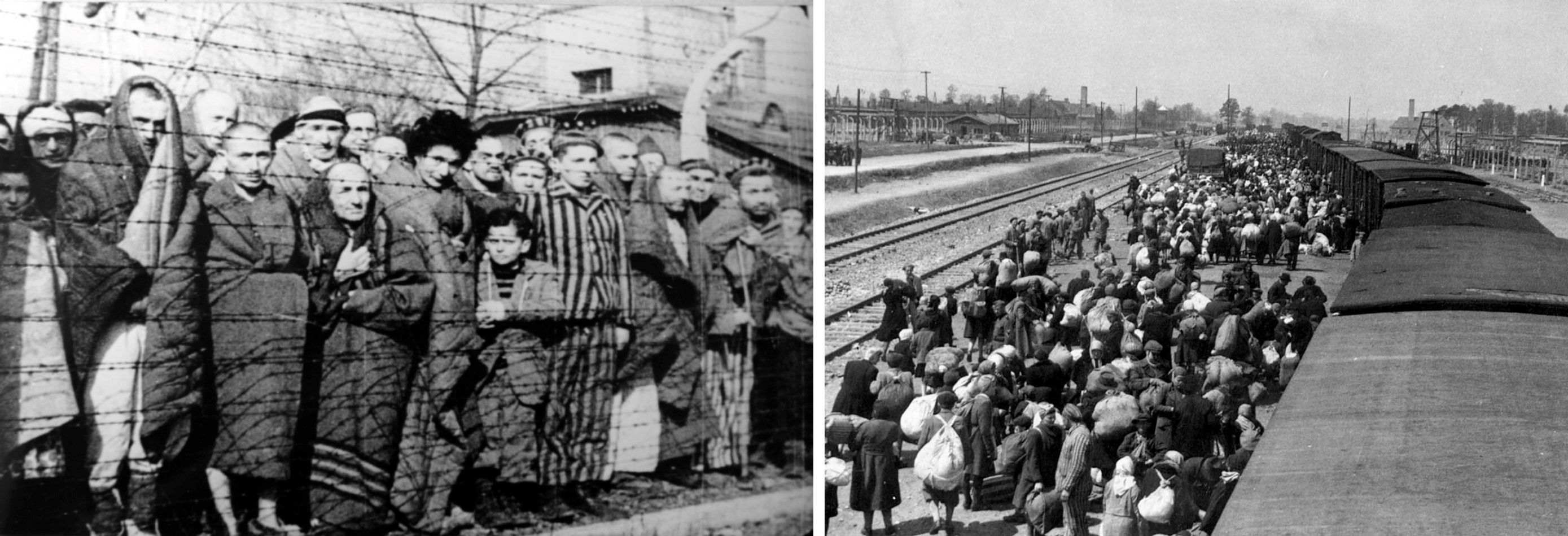

However, it is as a Holocaust film that Denial finds its most compelling voice.

Early on, the team has to go to Auschwitz to prepare their defense. Jackson’s camera lingers on water droplets falling off barbed wire as Lipstadt becomes infuriated at what she falsely sees as her lawyer Richard Rampton’s callousness. For his part, Rampton is off walking the perimeter of the compound, calculating distances which will prove in the trial one of the final nails in the coffin of Irving’s case.

Entrance gate of Auschwitz Concentration Camp, "Work Sets You Free," 2013.

The moments in Denial at Auschwitz most recall Claude Lanzmann’s documentary, Shoah (1985), a massive film that begins with a survivor brought back to a concentration camp to experience the sacred space anew. Lanzmann uses such “b-roll” to sculpt the shape of his ten-hour film, which is mostly otherwise devoted to interview footage of the survivors telling us directly about their experiences in the camps.

The refusal of Lipstadt’s defense team to allow survivors to testify (because Irving will be able to abuse them on the witness stand) is a point of contention in Denial. By echoing Shoah in its sequences at Auschwitz, Denial brilliantly engages the question of survivor testimony at a meta-cinematic, rather than merely at a plot, level.

Prisoners at Auschwitz-Birkenau at liberation, 1945 (left), and Jews arriving at the camps, 1944 (right).

But it is Denial’s final shot that firmly cements it in the position of critical realism.

Lipstadt wins the case, and goes out running, as has been her mechanism for stress relief through the film. As she runs past a sandwich board advertising a newspaper’s summation of the verdict—“he lied”—Lipstadt stops in front of a statue of Boadicea, a Celtic queen who led her people in an uprising against the Roman Empire. Here, the film seems to deliver its final pronouncement, one of positivist victory over the lies told by the irrationialist Irving. And indeed, the film does just that, with a triumphant crane into the air, and melodramatic music by Howard Shore.

Interior of the crematorium at Auschwitz I at the museum, 2012.

However, the film does not end there. Instead, Jackson cuts back to snow beginning to cover the ruins of the shower complex at Auschwitz. The defense team had earlier in the film stood there, examining what the Nazis had detonated, a crass attempt to hide their atrocities. Indeed, the outcome of the trial partly hinges upon this destroyed structure, as one of Irving’s denial claims is about the architecture.

As Jackson’s camera lingers on the rubble of the complex, his film invokes the ending of Alain Resnais’ Night and Fog (1955), a modernist half-hour documentary about the Holocaust. Most of Night and Fog is black and white compilation footage of the Shoah, but even a mere decade after the liberation of the camps, the modernist Resnais is already worrying about the diminishable power of the footage which comprises his film. To grapple with this crisis, he bookends the film with color footage shot in the present, among the ruins of the camps.

With stunning modernist music by Hans Eisler and poetic voice-over narration worrying about who was responsible for the atrocities if not those on trial at Nuremberg, and who will keep such brutality for recurring, Resnais’ film voices the critical realist position. Photographic evidence will not be enough; positivism will fail us.

Instead, we must marshal our full aesthetic capabilities to keep interrogating the past for its relevance on the present, again and again without cessation.

Memorial at the reconstructed gassing chambers Auschwitz, 2012.

As a sophisticated film referencing other Holocaust cinema, Jackson’s Denial pushes beyond Lipstadt’s own work, finding a critical realist solution to the limitations of positivist reason. In a world in which Donald Trump will soon lead the most powerful nation on Earth, whose critiques of political correctness directly echo the bile spewed by David Irving, the need for such sophisticated cinema has never been greater.