"We have to do with the past only as we can make it useful to the present and the future."

LA 92 The Past is a Prologue opens with this quote from Frederick Douglass and its message drives the documentary. Oscar-winning directors Dan Lindsay and TJ Martin endeavored to create a film that explored Los Angeles in the spring of 1992 from multiple perspectives with the hope of providing fresh insight on six days of civil disobedience that brought Los Angeles, California to a standstill in April 1992.

They do this by relying primarily on archival news footage that captured immediate reactions around the city. This footage includes interviews with protestors, business owners, and other concerned citizens. The filmmakers seek to highlight connections between the past and present by juxtaposing footage from urban protests in the 1960s, 1990s, and in 2015. The film ends by incorporating images from contemporary urban protests next to the coverage of clean-up efforts in L.A.

Lindsay and Martin begin the film by looking back thirty years to the Watts Rebellion that took place in August 1965. From there, the documentary creates a portrait of the racial and ethnic diversity as well as the class and political divisions that polarized Los Angeles leading up to the explosion of civil unrest from April 29th through May 4th, 1992.

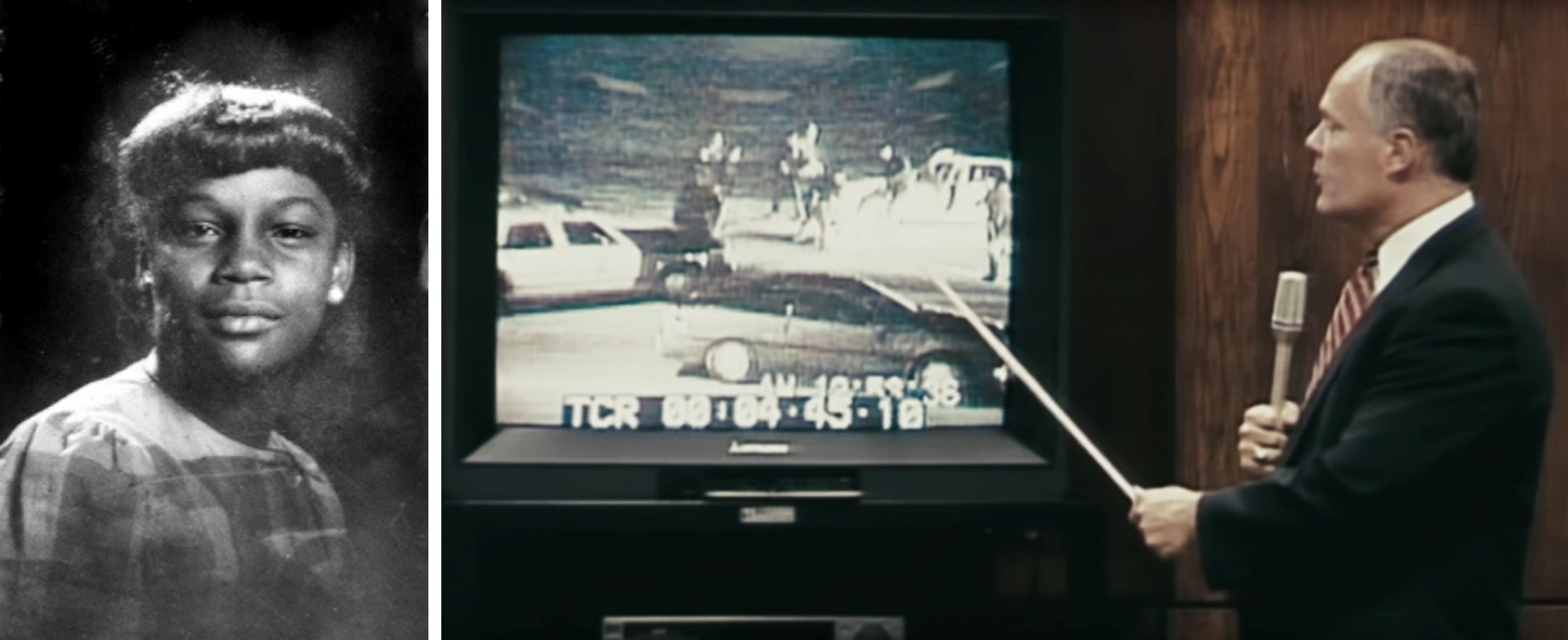

The film identifies two court decisions as catalysts for the events. One is Judge Joyce Karlin’s minor sentence, which included no jail time, handed down to Soon Ja Du, who was caught on tape shooting Black teenager Latasha Harlins. The second, and better remembered, was the not-guilty verdicts in the trials of the four police officers who were videotaped viciously beating Rodney King.

Slain teenager Latasha Harlins; the film’s treatment of property versus human life left something to be desired (left); a scene from the trial of police officers who beat Rodney King (right).

The directors succeed in capturing a multitude of reactions to the trial verdicts and subsequent outbreaks of civil disobedience. The archival footage catalogues Los Angeles’s economic and racial diversity. But, the documentary shows that it was not always possible to anticipate an individual’s response to the events solely based on racial identity. Class, age, and property ownership also shaped how people responded to what was happening around them.

The choice to place footage of distraught business owners next to coverage of families and communities reeling from extrajudicial violence runs dangerously close to equating property damage with human bodily suffering or loss of life. While one may empathize with small business owners who watched their life’s work burn, it simply cannot compare with grief felt for a slain teenager.

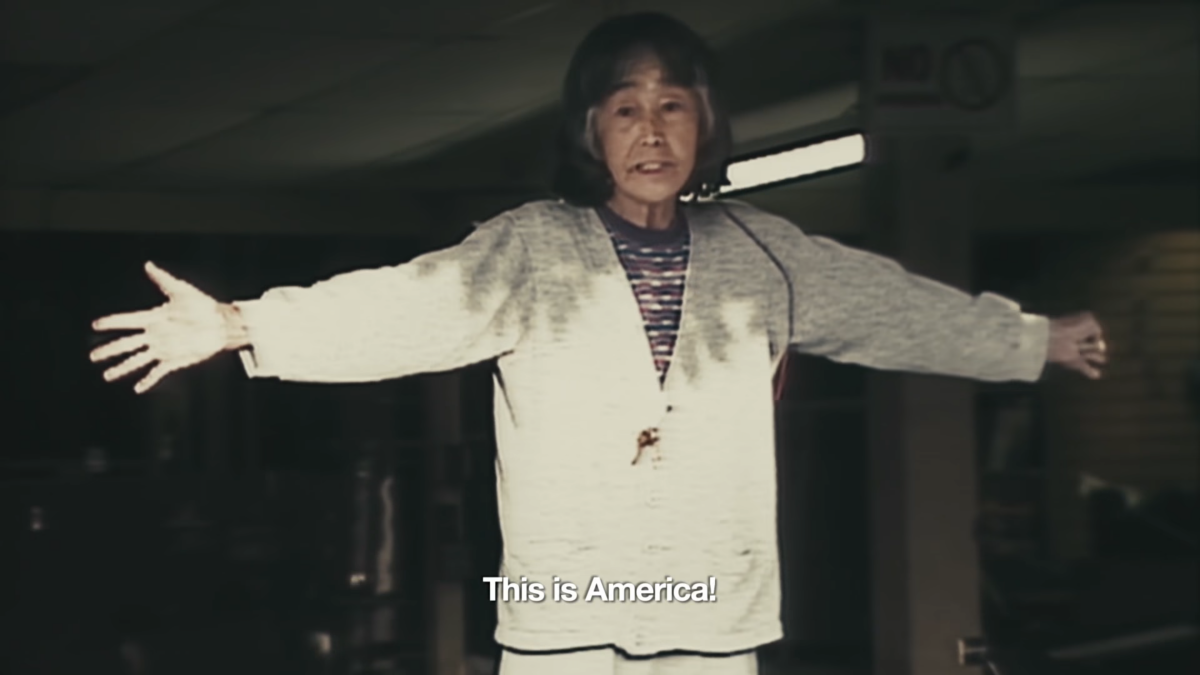

Viewers react to the Rodney King trial verdict.

LA 92 is not a sophisticated analysis of U.S. race relations. However, the filmmakers' attention to the perspective of Asian, especially Korean and Chinese, communities, as well as Latino Angelenos effectively pushes the memory of these protests beyond the black-white binary that often defines the story of race in America.

Protests during the 1992 Los Angeles riots.

A highpoint of the film is the inclusion of Congresswoman Maxine Water’s speech at a Congressional Black Caucasus press conference in 1992 amidst the urban rebellion. Congresswoman Waters explained, “I am angry and I have a right to that anger and the people out there have a right to that anger.” Here the filmmakers characterize protest participants as people determined to assert their humanity rather than solely as violent, irrational looters and criminals.

There are some missed opportunities. For example, the directors might have utilized images of black manhood as they examined the verdicts of the police officers who attacked Rodney King. Did ideas about Black hyper-masculinity color public perception about whether officers used excessive force against Rodney King?

Police approach a man on the ground during the Los Angeles riots.

Adapted from the famous line in Shakespeare’s Tempest, the documentary is subtitled “The Past is a Prologue.” By borrowing it, the directors signal their desire to show that contemporary racial conflicts have deep historical roots. The film succeeds in some measure. But, by replaying scenes of black people being brutalized it raises another troubling question: at what point do visualizations of black suffering become another form of dehumanization?

LA 92 successfully documents the Los Angeles uprising from multiple perspectives, but should also encourage us to reconsider the usefulness and limitations of looping videotaped Black trauma.

[Unless otherwise noted, images are screencaps from LA 92 trailer.]