The National Veterans Memorial and Museum (NVMM) in Columbus, Ohio is the first national memorial or museum dedicated to honor all United States veterans, regardless of branch of service or if they served during war or peace.

The National Veterans Museum and Memorial in Columbus, Ohio.

The museum, as its mission statement explains, exists to fill “the pressing need to honor the legacy of the courageous men and women who answered the call for our country. We must carefully preserve not only the names, dates, and battles but the intimate memories, personal belongings and painful losses of our nation’s Veterans.”

The idea of building a veterans' museum originated with the late Ohio Senator John Glenn. Construction on the “Veterans Memorial Museum” began in 2015, and in June 2018, an act of Congress designated the unopened museum as the National Veterans Memorial and Museum. The NVMM is the first national museum to receive this distinction without first opening its doors to the public.

By the time the NVMM opened on 27 October 2018, Architectural Digest had already hailed it as one of the most anticipated buildings of 2018. The museum's impressive circular design spirals up from the ground, creating harmony between the structure's elevation and its surrounding topography.

The museum's circular design continues in its interior.

Beyond the building itself lies a 2.5 acre Memorial Grove, containing many varieties of trees, a water feature, memorial wall, and monuments for fallen service members. Located behind the building, the grove is isolated from the nearby road and sounds of the city, and serves as a place for quiet reflection.

For all the praise for its design, however, the layout poses real difficulties for elderly visitors and veterans who cannot walk well. Guests have to walk around the outside of the building to enter the museum at the top of the hill—an obstacle for many who want to visit, even with the benches placed on the path as rest stations. The building is beautiful, to be sure, but the planners and architect seem to have forgotten their potential audience.

Inside, the museum distinguishes itself from a traditional war museum's straightforward narrative of America’s wars. Instead, the NVMM tells visitors about the experiences of America's veterans by presenting the stories of 25 individuals.

The NVMM's exhibits chronicle the stages of a veteran's experience.

Chosen with the help of a veterans advisory committee from a pool of 250 potential candidates, the 25 people at the center of the museum's exhibits are representative of a larger collective and shared veterans’ experience. All of their stories follow a similar path: beginning with the individual's motivations for joining the military, the museum recounts the training each individual received at boot camp and the details of their service prior to being discharged—the moment when they each became a veteran.

Despite its “national” designation, much of the NVMM's content currently reflects its original mission as an Ohio-centric museum and memorial. Several of the veterans are from Ohio, and the majority of the artifacts currently on display are on loan from the Motts Military Museum (Groveport, Ohio), Ohio History Connection (Columbus, Ohio), and Ohio State University Libraries (Columbus, Ohio). The museum is planning to add to the artifacts on display through the development of its own collection.

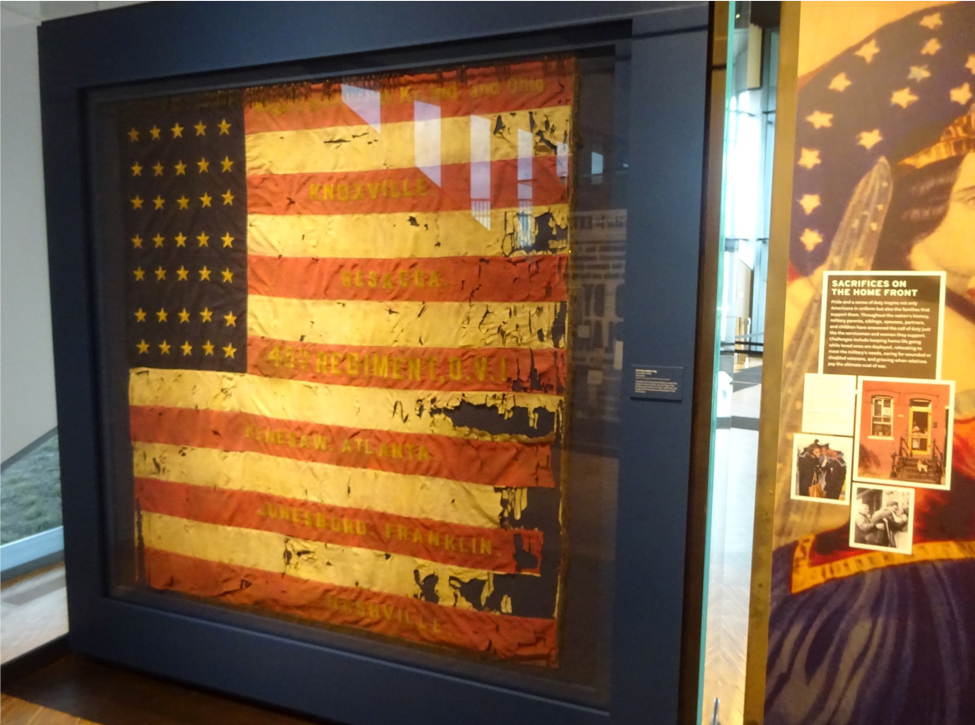

A Civil War flag from the 44th Ohio Voluntary Infantry Regiment on display at the museum.

The museum loosely defines a veteran as an individual who took an oath and served in the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, Air Force, or Coast Guard. What it doesn't explore in any depth, however, is the question of what really distinguishes a veteran from a civilian in America.

The differences between a civilian and an active-duty soldier or sailor are easy to point out, but what makes a veteran’s post-service life meaningfully different than someone who hasn’t served? And what are the shared experiences of all veterans that make them into a distinct group?

A multimedia display showing the wide variety of professions within the military.

The majority of the collection focuses on telling the story of America at war, rather than telling the story of life after war—or after service—for veterans.

The museum's timeline starts in 1775 and ends with the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. It also features individual panels honoring distinguished veterans like John Glenn and John McCain.

Notably missing from the timeline are the creation of the Marine Corps, Coast Guard, and Air Force and battles like Okinawa. The timeline also stops after 1975 and resumes in 1990. This excludes an important period for the U.S. military with peacekeeping operations in the Sinai and deployment to Panama.

This curatorial decision contradicts the museum’s stated mission of being inclusive to all veterans regardless of length or era of service and whether they served during peace times.

Despite its shortcomings, the NVMM is still a profound and eloquent space, especially for the veterans who visit it.

One museum volunteer relayed to me how a veteran took them aside to say that his coming home story mirrored that of one highlighted veteran: changing out of his military uniform to avoid unwanted attention as he coped with his transition to civilian life. Despite the amount of time that had passed since then, the veteran said, the museum’s movies and narration were so touching that the memory made him break down and cry.

Another volunteer discussed the difficulty of sending a child off to war with an older visitor. The visitor, who had gone through the same experience, understood her feelings all too well.

The museum’s ability to connect visitors regardless of status as a volunteers, civilian, active service members, or veterans is proof that the NVMM fills a valuable and consequential niche in our history and culture.

To plan a visit, start with the museum’s excellent website.

The entrance to the National Veterans Museum and Memorial.

All photos by the author.