Seventy-five years ago, in late summer 1943, famed war correspondent Ernie Pyle sat above a newly constructed port in Sicily—the island near Italy's toe that Anglo-American forces had invaded in early July—taking in the scene below. Pyle had sailed with Allied troops across the Mediterranean from North Africa.

Before D-day in Normandy eleven months later, the Sicily campaign—Operation Husky—was the largest seaborne invasion in history, involving an astonishing armada of nearly 3,000 ships. “There is no way of conveying the enormous size of that fleet,” wrote Pyle. "On the horizon it resembled a distant city. It covered half the skyline....Even to be part of it was frightening."

U.S. tanks in Tunisia in July 1943 prior to Operation Husky.

Those ships delivered 180,000 soldiers onshore but also 14,000 vehicles, 600 tanks, and 1,800 large guns—half of this huge quantity during the attack's first 48 hours. Many landing craft carried not people but supplies; 20 carried water alone. In subsequent days, other supplies would follow: food, fuel, ammunition, spare parts, medicine, maps, cigarettes, tents, radios and telephones, and much, much more—everything that a modern army needed, and modern armies needed a lot.

“We kept pouring men and machines into Sicily,” Pyle observed, “as though it were a giant hopper.”

American abundance of natural resources—and the ability to mobilize and focus them—gave the Allied soldiers, sailors, and airmen a tremendous advantage.

An assembly line near Niagara Falls, NY producing fighter planes for the American war effort.

Watching the mountain of supplies on Sicily’s shores grow higher and higher, an idea dawned on Pyle: “Suddenly I realized what all this was. It was America’s long-awaited power of production finally rolling into the far places where it had to go.”

That power of production helped win the war. “To a large degree, the improvement in the military situation [in 1943],” historians Robert Coakley and Richard Leighton have written, “was a result of the huge outpouring of munitions from American factories and of ships from American yards.”

World War II was a war of thousands of guns, tanks, and planes—a “gross national product war” according to one historian. It was a total war—a mobilization of nearly all human and natural resources.

Tanks rolling off a German assembly line in 1943.

That meant it was also a war that shaped and was shaped by nature. “When we send an expedition to Sicily, where does it begin?” observed President Franklin Roosevelt two weeks into the campaign. “Well it begins at two places practically. It begins on the farms of this country, and in the mines of this country.”

Wars can be understood many ways—strategically, politically, economically, socially, personally. But also environmentally.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt understood the importance of supply lines, and knew that America's farms and mines were vital to the war effort.

In World War II, geography and weather shaped battles, and battles re-made landscapes, often dramatically. The war also remade landscapes far from battlefields—through extraction, transport, processing, and pollution, but also through new technologies, organizational strategies, and ideas.

“Obviously the areas where war is actually being fought are violently injured,” the conservationist Fairfield Osborn wrote in 1948, “Yet the injury is not local but leaves its mark even in continents far removed from the conflict because of the compelling demand that war creates for forest and agricultural products. These are in truth poured into the furnace of war.”

Fuelling the furnace of war in the mid 1940s reconfigured American relations with the natural world in long lasting ways.

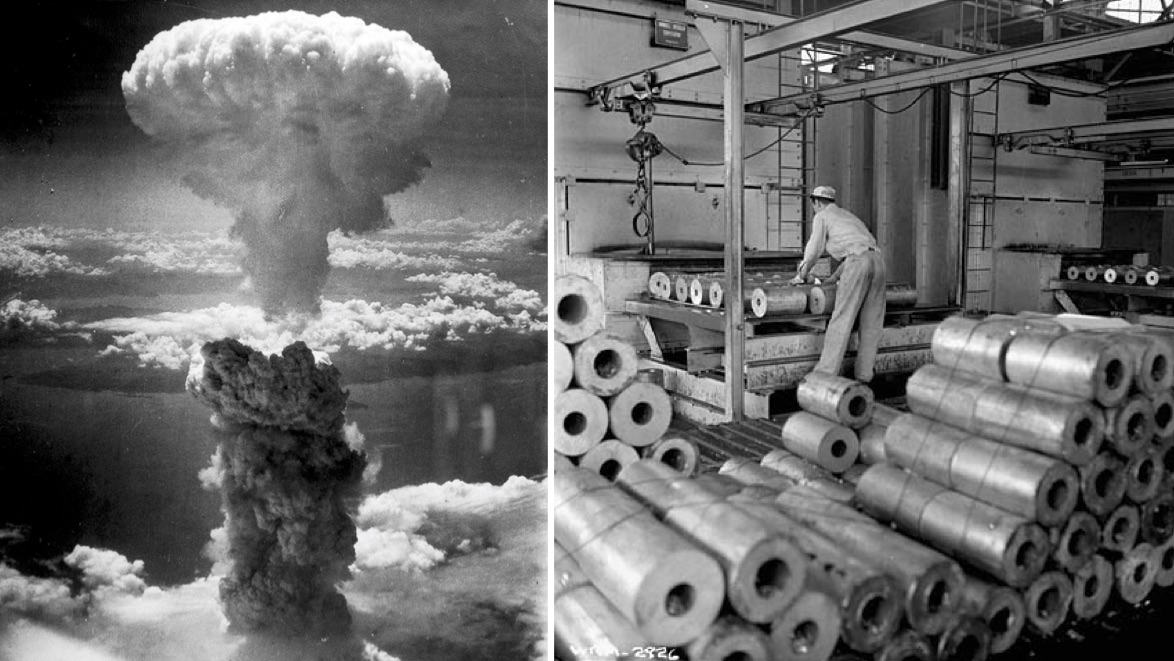

World War II ushered in an age of new techology, such as atomic weapons, seen here being used on Nagasaki in 1945, and aluminum, like the rolls this worker is manufacturing.

To begin with, great changes flowed from the nation’s vastly expanded productive capacity, which grew by 50% from 1940 to 1945, as well as from the extraction of materials from farms and mines needed to fuel it.

New tools invented or vastly transformed and popularized by the war also reshaped American relations with nature—atomic weapons, synthetics like plastic and nylon, new metal alloys such as aluminum, drugs like penicillin, DDT, insecticides and herbicides, bulldozers (what Pyle called the “magic instruments” of the war), airplane technology including jet engines, sonar, assembly-line house construction, and the first computers. New “machines of wizardry,” David Lilienthal gushed in 1944, spun out “the stuff of a way of life new to this world.”

New technologies also came with downsides, such as pollution, seen here in a smog-covered Los Angeles.

Combined with vastly expanded production, these new technologies dirtied the nation’s air and water in new ways and on a new scale. Because of skies darkened by smoke, steel towns like Pittsburgh had to turn the lights on during the day. Smog smothered Los Angeles. Michigan’s Willow Run, Seattle’s Boeing Plant 2, and hundreds of other military-industrial sites spewed the noxious pollutants that would eventually make many of them Superfund Sites.

In 1941, Hooker Chemical, a defense contractor, began dumping the toxic substances into Love Canal that decades later would seep into the basements of unsuspecting families, causing a national scandal.

The 1941 dumping of toxic substances into Love Canal turned into a national scandal in the 1970s after unsuspecting citizens were exposed to its effects.

Wartime imperatives also created a new military-industrial geography of extraction sites; chemical, munitions, and aviation factories; and hundreds of military bases linked by rail and new road, shipping, and air systems.

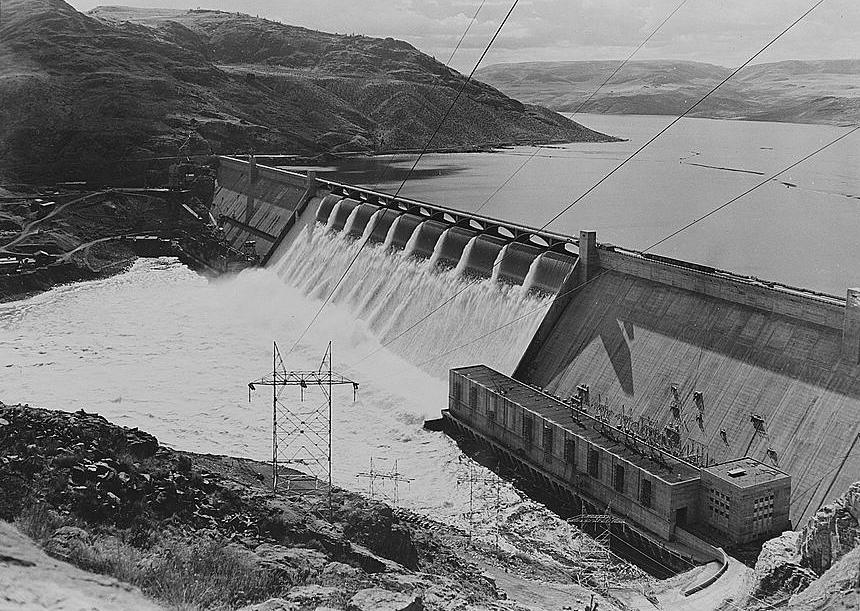

Speed took on new urgency. So did cheap, plentiful energy. Electricity generated by New Deal dams powered new wartime industrial corridors in the Pacific Northwest and Tennessee Valley. Cheap oil and its infrastructure remade the Gulf Coast. In the search for new energy, physicists blazed new trails in America’s sub-atomic landscape.

Washington state's Grand Coulee Dam, constructed between 1933-1942, helped to power new industrial corridors in the Pacific Northwest.

In the process, the war engineered a military material culture that would shape daily life for decades.

To the extent that we live in northern cities or the Sunbelt, work at defense industries or companies that support them, eat processed food from fertilizer-fed fields (and cover left-overs in saran wrap), smoke cigarettes (subsidized for soldiers), travel by airplane, wear and use petroleum-based clothes and products, use aluminum and a host of alloys, and rely upon antibiotics when we get sick, we are following patterns of life pioneered and popularized during World War II.

New ideas also sprang up.

The destruction new technology wrought at Hiroshima and Nagasaki helped fuel a growing skepticism of its uses.

Depression era restraint gave way to no-limits optimism. Keynesian ideas of a consumption-driven “growth” economy took root. Guns and butter seemed newly possible. A “can do” techno-optimism—the motto of the Seabees—suggested that no natural hurdle was too high for American “know how.”

A counter response also sprouted. Deep skepticism of technology emerged, even before Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Ecological views of environmental degradation and resource limits took hold. Awareness of pollution grew. The global conflagration transformed the thinking of Aldo Leopold, William Vogt, Rachel Carson, David Brower and other architects of the postwar environmental movement.

As awareness of pollution grew, so too did the burgeoning environmental movement.

In sum, the war forged the world we live in—not just the political and economic order but also the built environment, material culture, and intellectual topography, not to mention American landscapes near and far. The need to supply Allied troops—to create the “might of material” that Ernie Pyle observed arriving in Sicily 75 summers ago—spurred many of these changes.