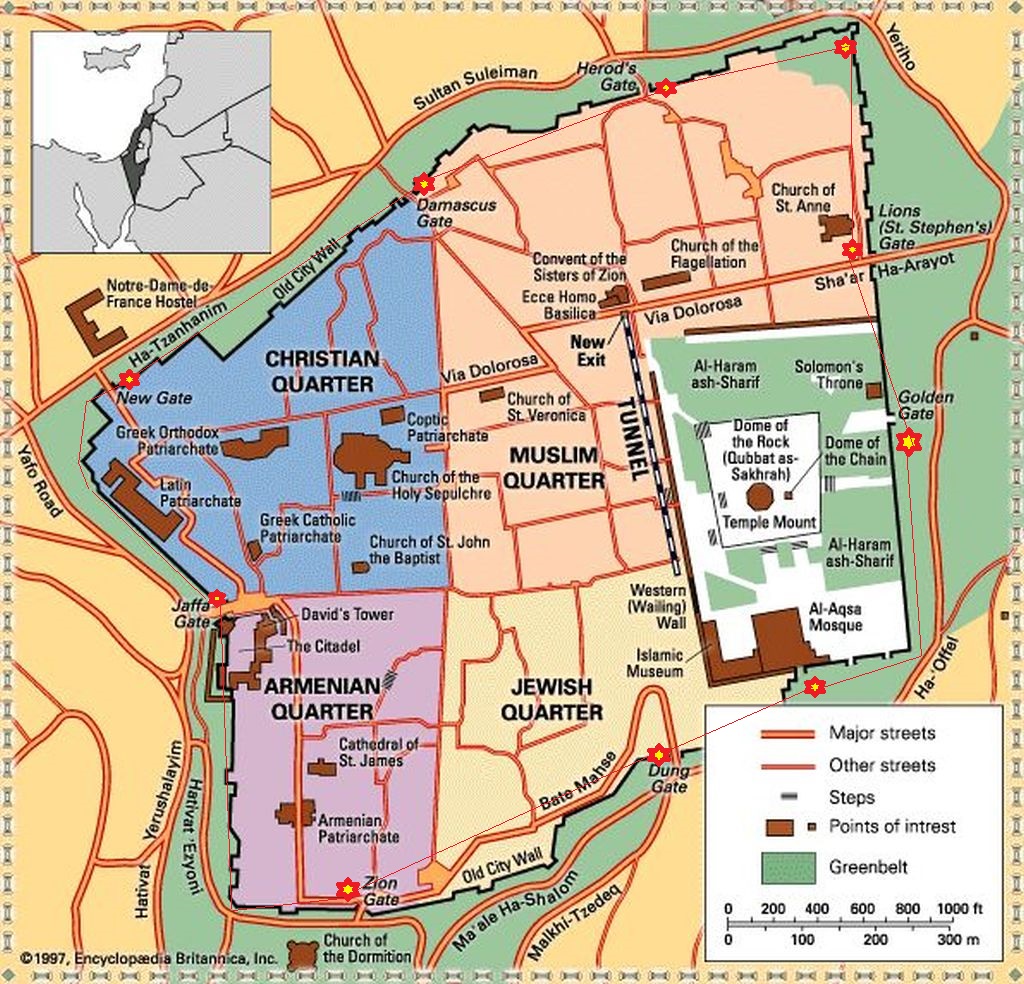

Map of the Old City in Jersualem.

As it has for thousands of years, Jerusalem remains a place of where many religions, cultures, and languages coexist, albeit not always peacefully. Inherent tensions continue today and are arguably exacerbated by current political forces. Jerusalem has made headlines recently because of President Trump’s announcement that he will move the United States Embassy in Israel to Jerusalem.

Condemned by leaders around the world, the move recognizes Jerusalem as the capital of the Jewish state implies that Jerusalem is only for Jews. This idea contrasts the long history of Abrahamic faiths mingling in their shared holy city, although with spurts of religious violence. Only time will tell if truly peaceful coexistence will ever be a reality.

Entering Old Jerusalem through the Cardo: Connecting Abrahamic Faiths

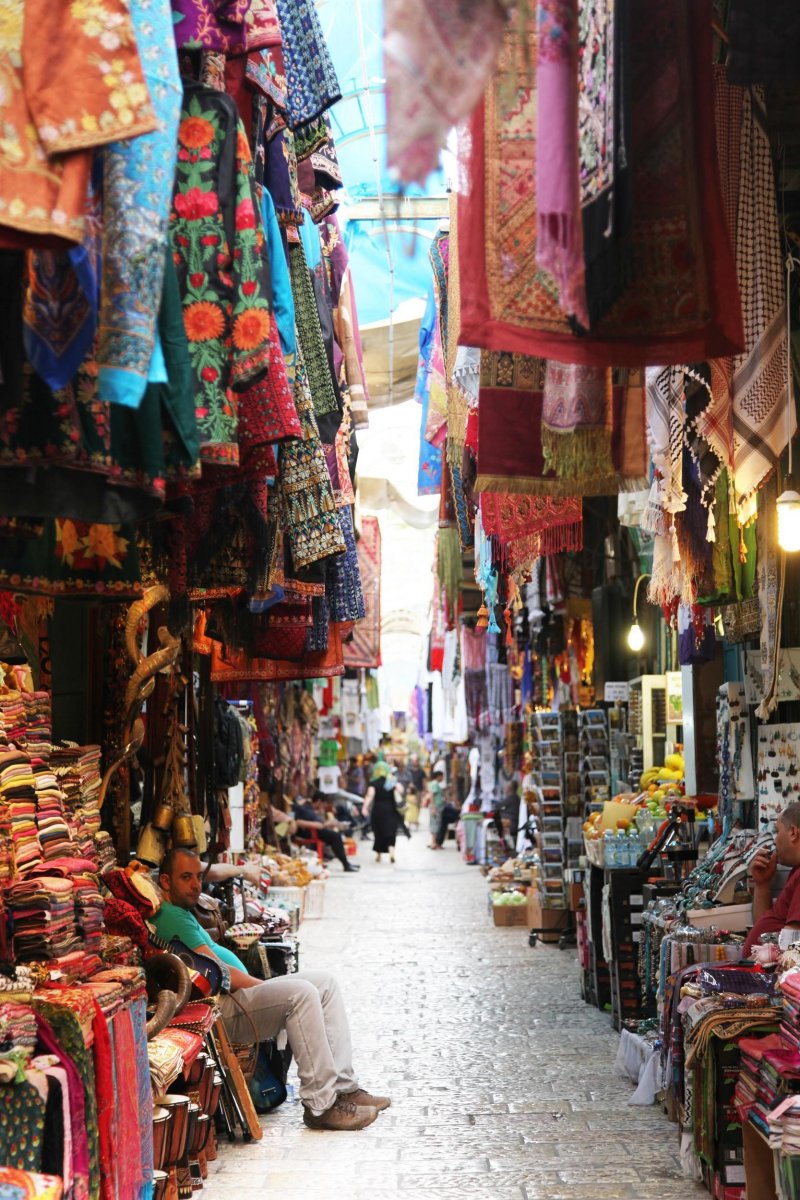

A shopkeeper sits outside his store in the Cardo waiting for tourists and residents to stop in.

“The Cardo,” Jerusalem’s ancient main street, runs north-south, typical of ancient Roman cities, and now traverses all areas claimed by Muslims, Christians and Jews. Since the 6th century CE, the Cardo has witnessed continuous trading among merchants and peddlers, and been used by travelers and residents as they walk between the Damascus and Zion Gates.

Jesus Christ’s Final Journey

Christian pilgrims kneel to pray where it is said that the body of Jesus Christ was anointed before burial.

The New Testament not only narrates Jesus Christ’s childhood in Jerusalem, but also describes his walk up a path now named Via Dolorosa (Way of Sorrow) for his crucifixion. Christians believe that his crucifixion and tomb lay near the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. Built in 335 CE and rebuilt in 1048 CE after a demolition by a Fatimid Caliphate ruler in 1009 CE, the church serves as one of many major pilgrimage points. The interior of the Church has been split as different denominations claimed worship spaces. Syrian, Ethiopian, and Armenian Christians, Roman Catholics, and Greek Orthodox now each have a section. Visitors can observe processions of monks, priests, nuns, and pilgrims of different denominations walk by one another mostly in peace, though with occasional conflict.

Ethiopian Christians

Ethiopian monks relax in the courtyard of Dier Es-Sultan monastery.

A narrow stairway leads to Dier Es-Sultan, a contentious site atop the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. It now houses an Ethiopian monastery but it was not always this way. Ethiopians have lived in Jerusalem since 4th century CE. Then, in the 18th century, an Egyptian Coptic monk with his eight slaves came to take the site. In 1852, the Ottoman Empire made Dier Es-Sultan one of nine holy sites under the Status Quo, forcing Jews, Christians, and Muslims to share ownership of various sites with agreement to “leave things as they are.” At that time, the Copts wielded more power on that site than the small Ethiopian population and claimed that site as theirs. In April 1970, when the Coptic monks departed the site for Easter worship, the Ethiopians staked a majority claim with the help of the Israeli government.

Christian Armenians

A poster and the Armenian flag hang outside a restaurant to remind passersby of the Armenian genocide.

Nestled in the southwest quarter of the Old City, the Armenian Quarter has been inhabited since the 4th century when Armenians adopted Christianity and monks came to settle. Informally, they consider their quarter to be part of the larger Christian quarter but their language and culture separate them from their Latin, Greek, and Russian counterparts. Stores, schools, shops and other facets of Armenian life cluster around St. James Church.

The quarter also acknowledges more recent history: the genocide of 1915-1917. After the genocide, Jerusalem experienced an influx of Armenian refugees. Posters line its main street and Jerusalem-born residents tell their families' stories. One shopkeeper said that his grandfather came to Jerusalem as a toddler when his family fled from their homeland. Another shopkeeper told of his family’s arrival in the 1920s from western Armenia (now part of Turkey). Recently, this shopkeeper observed, Armenians have been emigrating not to Israel but to Australia, Canada, and elsewhere. With only 2,000 residents left in Jerusalem, he still hoped that Armenians will continue to claim their presence in this small quarter.

A Glimpse into the Muslim World

Elderly women sell produce near the Damascus Gate entrance.

Through the Damascus Gate, one descends the steps with hordes of tourists and residents to the lively Muslim Quarter’s bazaars, the Dome of the Rock, and the Al-Aqsa mosque. In the eyes of Islam, Prophet Muhammad journeyed to here and prayed before ascending to heaven from a stone in the Dome of the Rock, making this site the third holiest in the world after Mecca and Medina.

Palestinians Inside the Old City

Shopkeeper and his shirts, including an Ohio State one!

Right where Via Dolorosa meets El-Wad ha-Gai Street sits a shop owned by a Palestinian. Standing by his favorite shirt, he explains that it has been a “challenge” economically and politically to live in Jerusalem because of his Palestinian identity. Yet, he stresses that living in Jerusalem for many Palestinians like him provides a reason to be alive: to see the return of his homeland to Palestinian hands. His family has lived in the Old City for generations: where else could they go if not Jerusalem, their home?

Silwan: From Ancient Village to Endangered Neighborhood

Residents of Silwan gather for a celebration at their community center.

This is the same question the Palestinian residents of Silwan ask themselves in East Jerusalem. The community members gathered one evening for a celebration at their community center, which houses activities for kids ranging from art to computers. Giant plates of rice, salad, and meat were passed around. Children danced dabke, a Palestinian dance, for their guests. Music blared from one large speaker upstairs. “Our existence here is a form of resistance,” Zuhair, the community center’s founder said. From the upstairs of the center, you could see the walls of the City of David, an archeological site revered by Jews. This close proximity creates a threat to their neighborhood.

The Struggling Remnants and Revival of the Jewish Presence

Orthodox men pray at the Western Wall on the Jewish holiday of Shavuot, which marks both the wheat harvest and commemorates the day God gave the Torah to the Jews.

Jews have lived in Jerusalem since the rule of King David in 10th century BCE. While many Jews fled Jerusalem after the Romans’ destruction of the Second Temple in 72 CE, a small population remained in this quarter and survived under many occupations. For Jews, the “Western Wall,” one of many walls of the Temple Mount (Dome of the Rock) has served as a holy site for prayers. Muslims continue to control the property on the other side of the wall, including the Dome of the Rock.

The Residents of Mea Shearim

An ultra-Orthodox mother pushes her child while an ultra-Orthodox man walks by on his phone on Mea Shearim Street.

Nestled one kilometer from the Old City sits the second oldest Jewish neighborhood, Mea Shearim. When the first settlers arrived here in 1874, they read Genesis 26:12 where Isaac reaped hundredfold and God blessed him. Today men dress in black frocks of the Polish nobility from the 16th century and women don dark, modest outfits. The residents strictly adhere to the laws of the Torah. Two young women responded “Because of Ha-Shem (God)” when asked why they chose to live here. Their community desires to be close to Mount of Olives, where the Torah proclaims that the Messiah will rise. These Jews hope that their chosen lifestyle will permit them to be among the first to greet the Messiah. Despite their cultural outlook, they can be found chatting away on their smartphones alongside secular Jews on the streets.

The “Other” Jews at the First Train Station

A glimpse into the renovations at the First Station with tracks still preserved.

Further south from Mea Shearim is Jerusalem’s first train station, built in 1892, now transformed into an entertainment space. On Shabbat, the holy day of rest in Judaism, secular Jews come to play and eat at one of several cafes, some of the few opened in the city on that day.

Machane Yehuda Market

Jewish women pay for their produce at the Shuk.

In the heart of West Jerusalem sits Machane Yehuda Market, also known as the shuk in Hebrew. Locals and tourists shop for produce, tea, spices meat, and baked goods and bright clothes, especially on Fridays, the day before Shabbat. Vendors yell bargains while yellow posters promote Chabad, an Orthodox movement, as people sample dried fruits, nuts, and halva, a sesame cake.

Like the Cardo in the Old City, the shuk has witnessed transformations. Founded in late 1800s by Arab merchants, the market expanded under the Ottomans. Then during the British Mandate (1917-1947) the authorities cleared the market and built permanent stalls and the market was named “Mehane Yehuda,” a reference to its neighborhood. In the 1930s, Iraqi Jews began to sell produce there; this specific section of the market is now referred to as the Iraqi Market.

The shuk has not always witnessed peaceful gatherings: it suffered from two terrorist attacks, one in 1997 and another in 2002. As tourists shied away in fear, renovations arrived. Cafes and bars now sit alongside vendors, making the market still a wonderful place to people-watch, day and night.

[All photos by authors]