Madras was born in 1636, when East India Company official Francis Day signed a treaty with the Nayaka ruler to acquire three square kilometers of land, bounded by the Adyar river and the Buckingham canal in the south and north respectively, on the beach overlooking the Bay of Bengal.

Madras was an odd choice for a city because it had no existing port for trade, and cargo had to be transported from ships to the shore in small boats. Some sources suggest that Day was so enamored of his Tamilian mistress that he chose to settle the EIC where he could be near her and visit her frequently.

Nearly four centuries later, the EIC site and the surrounding villages have merged into one of the four “megalopolises” of India: Chennai city. Today, Chennai’s landscape reflects a number of European influences. The architecture of empire is still reflected in the architecture of prominent buildings throughout the city.

Perhaps the most obvious sign of this colonial influence in Chennai is Fort St George, the first British fortification in India. Built by the EIC in 1644, Fort St. George was the administrative and military hub of the British presence in south India. It continues to house most of the bureaucratic and administrative departments of the government of modern day Tamil Nadu state, including its Legislative Assembly. It is also home to the Fort St George Museum, a repository of mostly British-era paraphernalia, including enormous floor-to-ceiling portraits of various Governors and their wives.

The Fort St George Museum.

The EIC had a contentious relationship with missionaries, and forbade them to enter India, fearing that interference with local religious practices would lead to the destabilization of trade relations. In 1813, however, when the financially-strapped EIC needed loans from London, the British Crown insisted that in return for financial aid the Company would allow missionaries to proselytize freely in India. The legacy of this in Madras is clear: Churches of numerous denominations can be found across the city.

One of the earliest Churches was an unusual one – the Armenian Church, established in 1712 by traders all the way from Armenia.

Closer to Egmore Station is a more familiar edifice: the St Andrew’s Church. Originally intended for the benefit of the numerous Scotsmen in the Madras colonial army, this Church is more popularly known as “the Kirk”, reflecting its Scottish Presbyterian roots. The Kirk was consecrated in 1821.

The Armenian Church, established in 1712 (left), and the St Andrew’s Church (right).

Perhaps the main justification for British colonialism in India was the ostensible concern about the low status of women in Indian society. Both British administrators and elite Hindu men agreed that improving the status of women in Indian society was vital to the project of moving towards a less “backward” and more “modern” society and culture.

One of the ways in which women could be brought into the public sphere was through education. While other colleges had admitted women students a couple of decades earlier, Queen Mary’s College was one of the first three women’s colleges opened in India in 1914.

Queen Mary’s College, opened in 1914.

While students in men’s colleges were studying mathematics, history, and the sciences; women at QMC were taught subjects intended to make them better homemakers and mothers, such as home economics. However, after their time in QMC, a number of women also made their way into professional colleges for teaching and medicine – usually at the Lady Willingdon College of Education (established in 1922) and the Madras Medical College (opened to women in 1875) respectively.

Lady Willingdon College of Education.

Though Presidency College was the first education institution established in Madras, the Madras University was the first institution of higher education in the Presidency (an administrative division of the British empire in India). Established in 1857, the University oversaw English education in the ever-increasing territory of the Presidency. Pictured here is the Senate House, the administrative and bureaucratic center of the University. Senate House is an exemplar of the Indo-Saracenic style of architecture, and was conceived of and executed by one of its leading exponents, Robert Chisholm, in 1879.

The Senate House at the University of Madras.

One of the hallmarks of the colonial encounter in India was the development of an extensive network of railways lines. The purpose of this remarkable railway network was to transport goods to promote British-controlled trade, and to move troops in order to subdue any nationalist uprising after the upheaval of the Revolt of 1857.

Built on the estate of a Portuguese merchant, Chennai Central Railway Station was constructed in 1873. It grew to be one the most important stations when it was made the headquarters of the Madras Railway Company in 1907. With its tall towers, Chennai Central is one of the most prominent examples of the Gothic style of architecture, which characterizes a number of colonial-era buildings in Madras.

The Chennai Central Railway Station.

Chennai Central is the hub of the Southern Railway, but it is not the only “central” railways station in Madras. Egmore Station, which handles all the south-bound train traffic, was completed in 1908. Initially, officials wanted to name this station after Robert Clive, better known in England as “Clive of India.” After much public debate, it was called Egmore after the locality in which it was built.

The Egmore Railway Station.

In addition to the railways, the most useful tool of communication for the East India Company, and later the British Crown, was the telegraph and postal system. After the revolt in 1857, British authorities took quick and efficient communication very seriously. Though there had been a fledgling postal system in India in the eighteenth century – after all, visitors to the Raj were keen to write home - the latter half of the nineteenth century saw rapid expansion telegraph services. The General Post Office in Madras was established in 1786, just outside the Fort. In 1884, it was shifted to its new home (pictured here) constructed in the Gothic style.

The General Post Office in Madras.

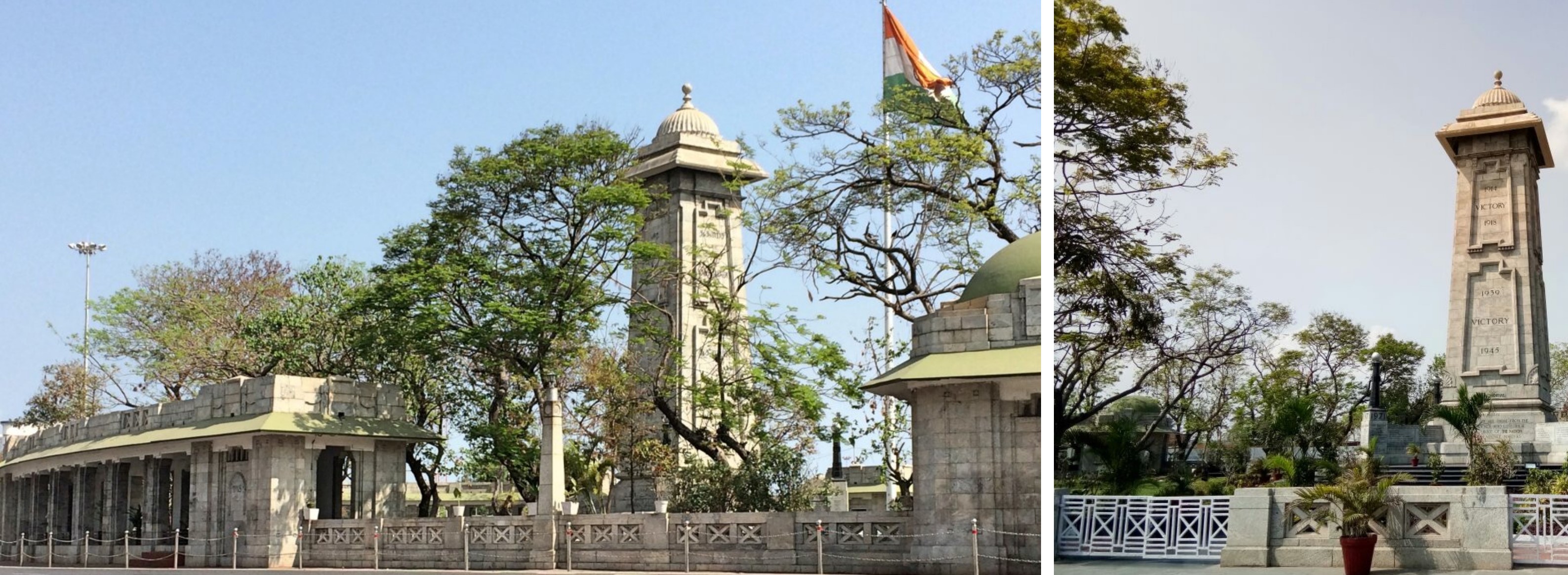

After the imposition of Crown Rule in 1858, when England went to war, so did her colonies. Indian soldiers became an integral part of the Allied war effort in both World Wars. Pictured below is one of the War Memorials in Madras. Although not as impressive as the India Gate in New Delhi, the War Memorial (earlier called “Cupid’s Bow”) was built after World War I to commemorate the allied victory. The building was added to after World War II, the Indo-Chinese War in 1962, and various Indo-Pak wars. Today, the War Memorial is squarely in the middle of one of Chennai’s busiest roads, with no pedestrian crossing to reach it! Taking a photo of the War Memorial therefore involves a swift and confident passage across a crowded road whilst adeptly dodging passing vehicles.

World War I War Memorial commemorating the allied victory.

Easier to access is the Emden memorial, which is simply a stone inscription tucked away into a wall of the High Court. It seems that people from Madras did not have to travel to Europe or North Africa to get embroiled into World War I – it was right in their backyard. On 22nd September, 1914, the German cruiser Emden sailed into the Bay of Bengal and shelled the city. Within minutes, two oil tankers exploded into flames. The shelling continued for thirty minutes, and the city was thrown into chaos for days. Thousands of people rushed to leave the city, and roads and railways were absolutely choked.

The Emden Memorial, in the wall of the High Court.

While the heart of “old Madras” in north Chennai remains stubbornly British – at least architecturally – Chennai is now an amalgam of this colonial heritage and influences from the villages surrounding the Fort, which were swallowed up by the city as it expanded.

[All photos by author]