Tirana is Albania’s capital and, with a population of nearly 1 million, over one-third of Albania’s inhabitants call the city home. What is now a bustling metropolis was until quite recently a grim Soviet-style city. In fact, the city is recovering from a difficult past that began under the oppressive rule of Enver Hoxha and continued into the post-socialist era with political corruption and failed pyramid schemes.

The cityscape is still dotted with reminders of this past, but the residents welcome visitors with true Albanian hospitality and intend to show the world that they are putting that history behind them.

Tirana sign in Taiwan Square. (Photo by Aleksej Demjanski)

A view of Tirana from Mt. Dajti.

Although the Tirana Valley has been continuously inhabited since the Bronze Age, it was not officially established as a town until 1614, when a mosque, bazaar, and Turkish baths were built at what is today’s city center. The city remained small during Ottoman rule, with a population of under 10,000 at the turn of the 20th century.

After Albania gained independence in 1912, Tirana became the new national capital in 1920, replacing Vlora in the country’s still-turbulent south. In 1939 the city succumbed to fascist forces and became the center of Italian and German occupation.

During World War II, the country saw the creation of the Communist Party of Albania, and after an intense battle in the capital against the occupying Nazi forces, the communists successfully seized power and Enver Hoxha emerged as Albania’s leader in 1944.

Communist Partisans in Tirana during the city's liberation in 1944.

Tirana under Communism

Following the example of the Soviet state, and with little regard for the historical sites of the city, Hoxha began a massive building campaign in which numerous Stalinist style apartments were constructed throughout the city, the Turkish baths and bazaar were demolished at Skanderbeg Square (city center) to make way for government buildings, and statues of Lenin and Hoxha himself were erected.

Aerial image of Skanderbeg Square in 1988.

Life under Hoxha is remembered by many as oppressive and the country became one of the most isolated in the world. The population of Tirana grew exponentially, but car ownership and religious practices were banned. Individuals suspected of conspiring against the state or those who tried to flee Albania were often shot on the spot. Foreigners were not allowed to enter Albania, nor could Albanians travel abroad.

As relations with Yugoslavia and the Soviets deteriorated, Hoxha’s paranoia drove him to construct thousands of bunkers, many of which still dot the countryside today. After a 40-year rule, Hoxha died in 1985.

With the revolutions of 1989 and the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the Democratic Party took power in 1992, and students demonstrating in Skanderbeg Square toppled the Hoxha statue.

An example of one of the many abandoned bunkers around Albania.

Tirana Today

Like many countries that emerged from behind the iron curtain, Albania’s transition to a capitalist economy was anything but smooth. By the late 1990s Albania was on the verge of bankruptcy and a series of pyramid schemes resulted in complete economic collapse and social unrest, draining wealth from families, and resulting in a large exodus of Albanians to Western Europe and the U.S.

In 2004, ten eastern European countries were admitted to the European Union. This sent a message to the Albanian people that it was possible for them to be incorporated into the larger European community and remove the country from the “periphery.” The Albanian people elected officials who promised reform and change. After 2004, Tirana began to transform into a vibrant European capital.

Rather than demolish the reminders of a communist past, the then Mayor of Tirana, Eddie Rama (now the country’s prime minister), began a campaign of refurbishment. The grey concrete buildings of the city were painted in vivid colors to reflect the bright outlook of the future. Empty spaces were turned into parks and complexes were filled with boutique stores and restaurants that fuse traditional cuisine with popular dishes from other European countries.

A characteristic example of the colorful buildings painted after the end of the communist era in Tirana.

The colorful buildings of Tirana, viewed from the steps of the National Museum.

An example of new construction and modern architecture in Tirana.

Although the baths and bazaar were demolished, Skanderbeg Square, in the heart of the city, is now flanked by the National Museum, government buildings, an Ottoman era mosque and clock tower, and a giant monument of Skanderbeg—the Albanian nobleman who led successful revolts against the Ottomans and Venetians in the 15th century and became the national hero after the creation of the nation-state.

The square is always full of life with children playing in the water features and crowds of people listening to free concerts, watching movie screenings, and enjoying firework displays.

Visitors to the National Museum begin their tour in the Neolithic period and follow the country’s history chronologically until finishing in a room that has a tribute to the hundreds of Albanians who lost their lives trying to escape the oppressive rule of Hoxha. It’s a somber experience to see in person, as bloodstained clothes, diary pages, and personal effects decorate the room, reminding the visitor of a not-so-distant past.

The National Museum in Tirana, Albania.

A monument dedicated to the 15th century Albanian nobleman Skanderbeg in Tirana's Skanderbeg square.

The Ottoman-era mosque in Skanderbeg Square.

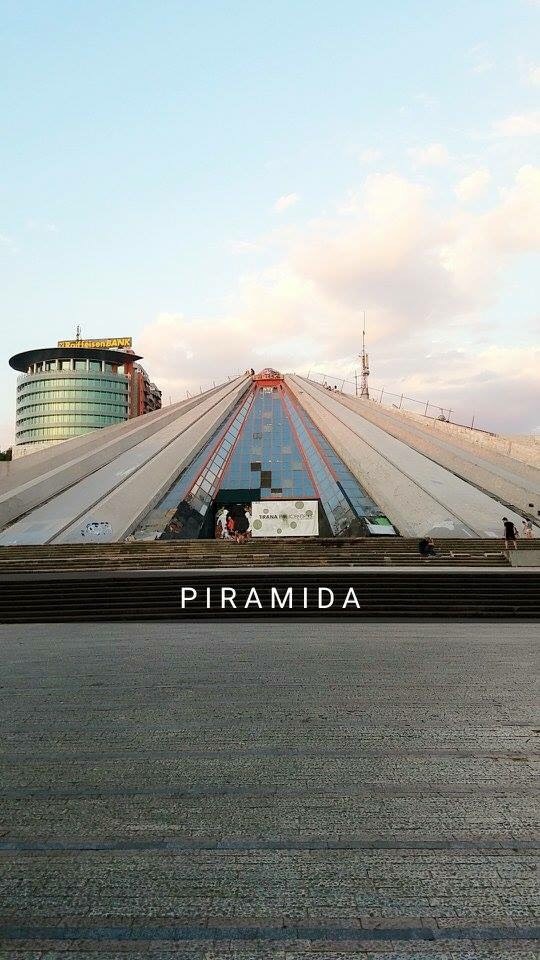

A popular spot and must-see for anyone visiting Tirana is “the Pyramid.” The Pyramid was originally a museum built for Enver Hoxha, but now sits abandoned. Covered in graffiti, it has become a spot for people to climb and take selfies.

To some the pyramid might be perceived as an eyesore, but many Tiranians do not feel this way. When I asked a local why the city has not torn down the abandoned building, his response was: “To destroy it would be to destroy our past. We see this building as a symbol of what we have overcome, and we climb it to show that we conquered the bad times.”

As Albanians conquer their past, Tirana has emerged as a beautiful city that attracts a growing number of European tourists.

"The Pyramid" in Tirana, a former museum for Enver Hoxha that is now abandoned. (Photo by Aleksej Demjanski)

[All photos by author unless noted]