Over the last year or so, the world of sport in the United States has focused on the phenomenon of pregame protests by professional athletes, sparked by the decision of (former) San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick to kneel for the national anthem during the 2016 season. That gesture, which has now spread throughout the NFL (and to other sports, even abroad), is by no means the first time athletes have used the field or court to voice political opinions.

1. “Drawing the Color Line” in the Late 19th Century

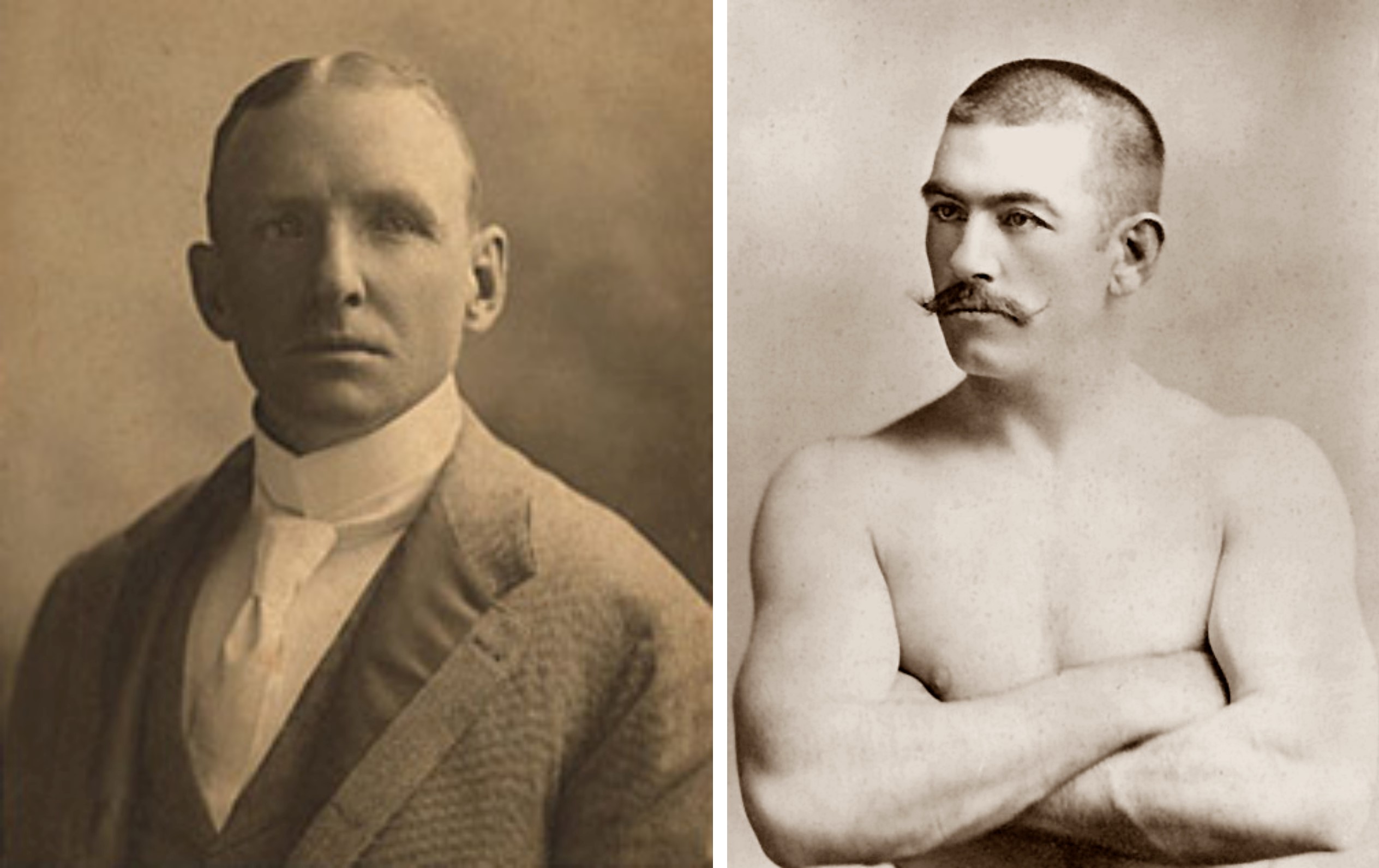

Chicago White Stockings baseman Adrian "Cap" Anson (left), and heavyweight boxer John L. Sullivan (right).

The use of protest and boycott techniques in sport has not always been politically progressive. Many of the earliest identifiable boycott or protest actions in American sport involved white athletes refusing to compete against or alongside African-Americans. On at least four occasions between 1883 and 1888, Chicago White Stocking baseball teams led by Adrian “Cap” Anson refused to play scheduled exhibitions against minor league teams featuring at least one black player. In 1887, eight members of the St. Louis Browns forced cancellation of an exhibition game between the Browns and the all-black Cuban Giants by declining to play. John L. Sullivan, heavyweight boxing champion from 1882 to 1892, repeatedly refused to defend his title against black opponents. The “color line” in American sport was not a product of drift or negligence; it was drawn.

2. The 1936 Summer Olympics

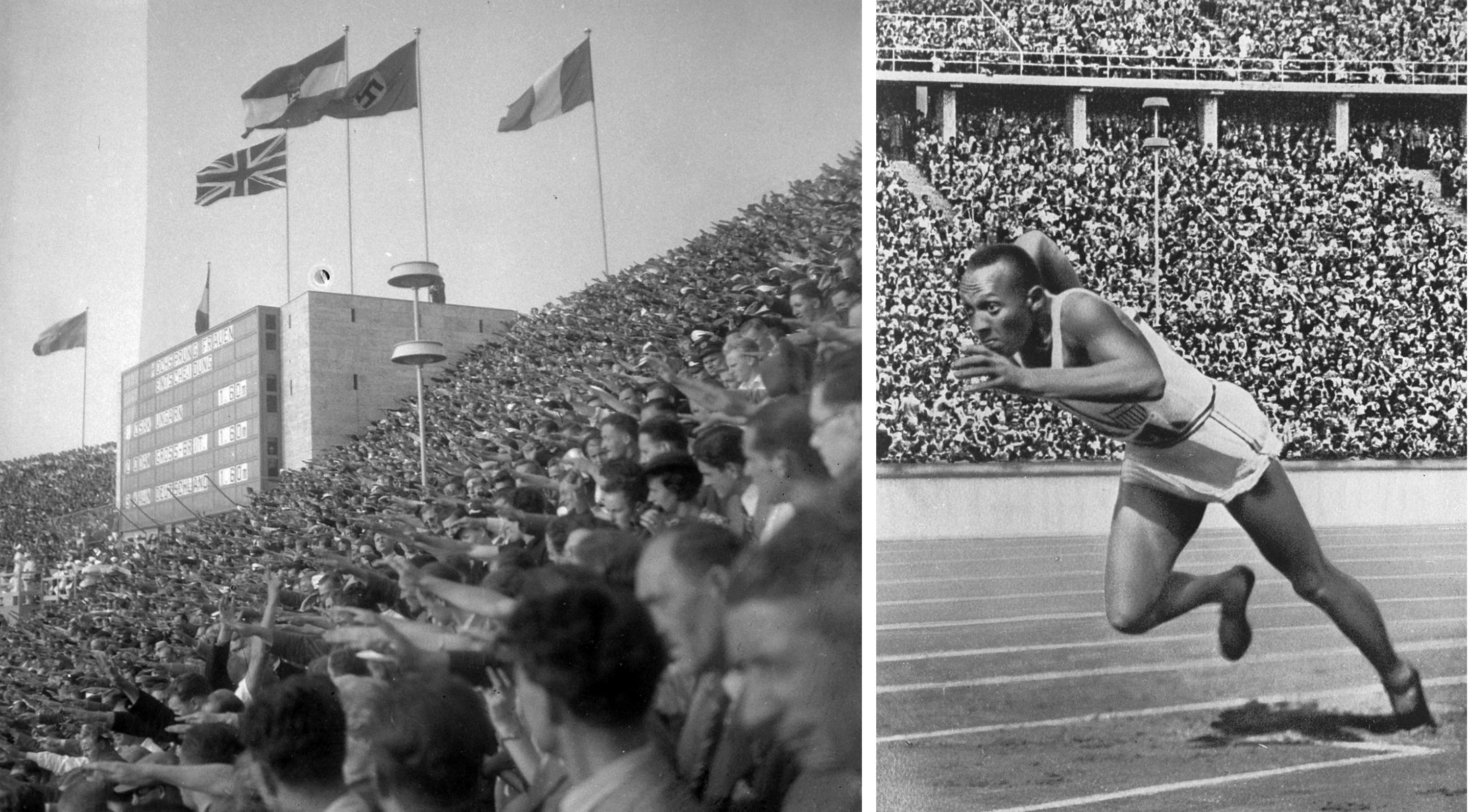

Spectators giving the Nazi salute at a medal ceremony in Berlin, Germany during the 1936 Summer Olympics (left), and U.S. sprinter Jesse Owens, who won four gold medals during the games (right).

The 1936 Olympics were awarded to Berlin in 1931, well before the Nazis took power in Germany. Once under Nazi control, however, the ’36 Olympics were programmed and presented as an explicit statement of Nazi racial ideology. They therefore also emerged as a potential target of antifascist protest. Efforts by American opponents of Nazism to pressure Germany not to discriminate against Jewish athletes, to force the IOC to move the Games, or convince American athletes to boycott them began as early as 1933, and accelerated as a result of surging anti-Jewish violence over the course of 1935.

Among the people or organizations calling for a boycott were the American Jewish Congress, New York mayor Fiorello La Guardia, New York governor Al Smith, AAU president Jeremiah Mahoney, and American Olympic Committee member Gus Kirby, who publicly denounced German discrimination against Jewish athletes at a 1934 rally in Madison Square Garden.

Some African-American athletes were torn between opposing Nazi racial ideology by boycotting the Games and the prospect of medaling at them thus disproving Nazi racial ideology. Ultimately, the American boycott movement was successfully suppressed by AOC president Avery Brundage, and coverage of the Games in the U.S. was dominated by the four-gold-medal performance of African-American sprinter Jesse Owens.

3. NYU “Bates Seven,” 1940-41

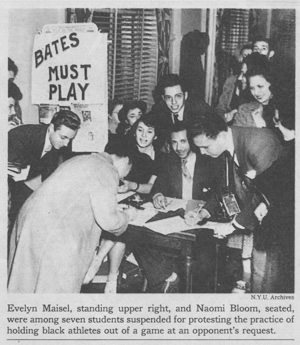

Unlike professional baseball, intercollegiate athletics outside the south were not uniformly segregated before World War II. They were, however, often subject to so-called “gentleman’s agreements,” whereby teams featuring black athletes might be asked to hold those players back when playing road games against segregated southern schools, or when playing in bowl games played in southern states. In the fall of 1940, the University of Missouri asked New York University (NYU)’s football team to hold back black starting fullback Leonard Bates from their upcoming game in Columbia, Missouri. NYU ordinarily respected such requests; Bates, in fact, had been informed of the possibility when he joined the team.

Once made public, however, the request led to a series of campus protests demanding that Bates be permitted to play. About two thousand protesters picketed the NYU administration building on October 18, wielding signs such as “Bates Must Play” and “No Missouri Compromise.” The protests didn’t end with the Missouri game – from which Bates was indeed held back – and continued on into 1941, as NYU continued to respect the “gentleman’s agreement” in other sports as well. Ultimately, seven NYU students at the forefront of the protest received three-month suspensions for circulating a petition without permission. “Gentleman’s agreements” began to fade after the war, though college athletics in the former Confederacy were among the very last institutions in the nation to desegregate in the wake of the civil rights movement.

4. The 1964 NBA All-Star Game Flash Boycott

Boston Celtics player Tom Heinsohn, a key figure in the 1964 NBA All-Star game flash boycott, 1962.

After World War II, professional athletes in a number of sports began to seek collective bargaining rights, focused especially on issues such as retirement pensions, per diems, and other workplace considerations. Owners and commissioners fought them. The National Basketball Players Association (NBPA) won its first concessions from league management as a result of an impromptu boycott threat mounted at the 1964 NBA All-Star game.

For the first time, the All-Star game was scheduled to be broadcast live in prime time. NBPA president and East All-Star Tom Heinsohn convinced other players to sign a petition threatening to boycott the game – and ruin the league’s prime-time broadcast window – unless the league agreed on the spot to bargain with the NBPA and institute a pension program. Despite efforts by several league owners to crash the locker room and talk players out of it, the boycott threat succeeded, and the league agreed to Heinsohn’s terms in order to get the game on air. Tip-off was delayed by several minutes.

5. Muhammad Ali

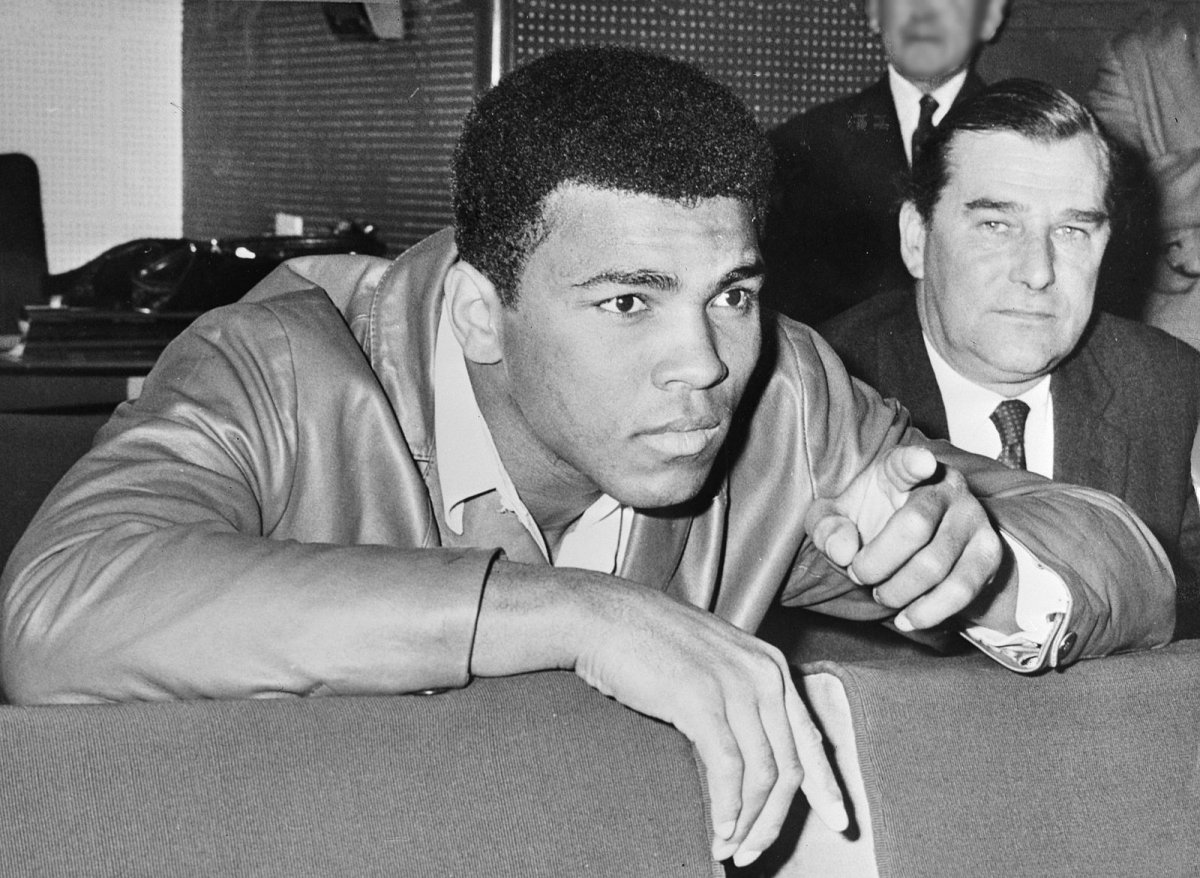

Muhammad Ali in 1966, the year he refused induction into the United States draft.

The most famous politicized athlete in American history is certainly Muhammad Ali, who risked jail time and lost several years of his career at the peak of his career due to his refusal to be drafted into the Army during the Vietnam War. Because Ali has subsequently been lionized as the platonic ideal of the political celebrity, it is easy to forget how polarizing a figure he was at the time. First known to fight fans as an entertaining braggadocio – complete with his own diss-track album on Columbia Records – he announced his membership in the Nation of Islam immediately upon becoming heavyweight champion in 1964 and was, for much of the 1960s, the world’s most famous black nationalist.

In the long run, his blunt opposition to the Vietnam War likely made him a more appealing public figure to Americans across divides of race, class, and culture, as opposition to American involvement in Vietnam was gradually accorded greater respect in the culture of the 1970s and 1980s. No other man has headlined both a national convention of the Nation of Islam and an episode of the Dean Martin Celebrity Roast.

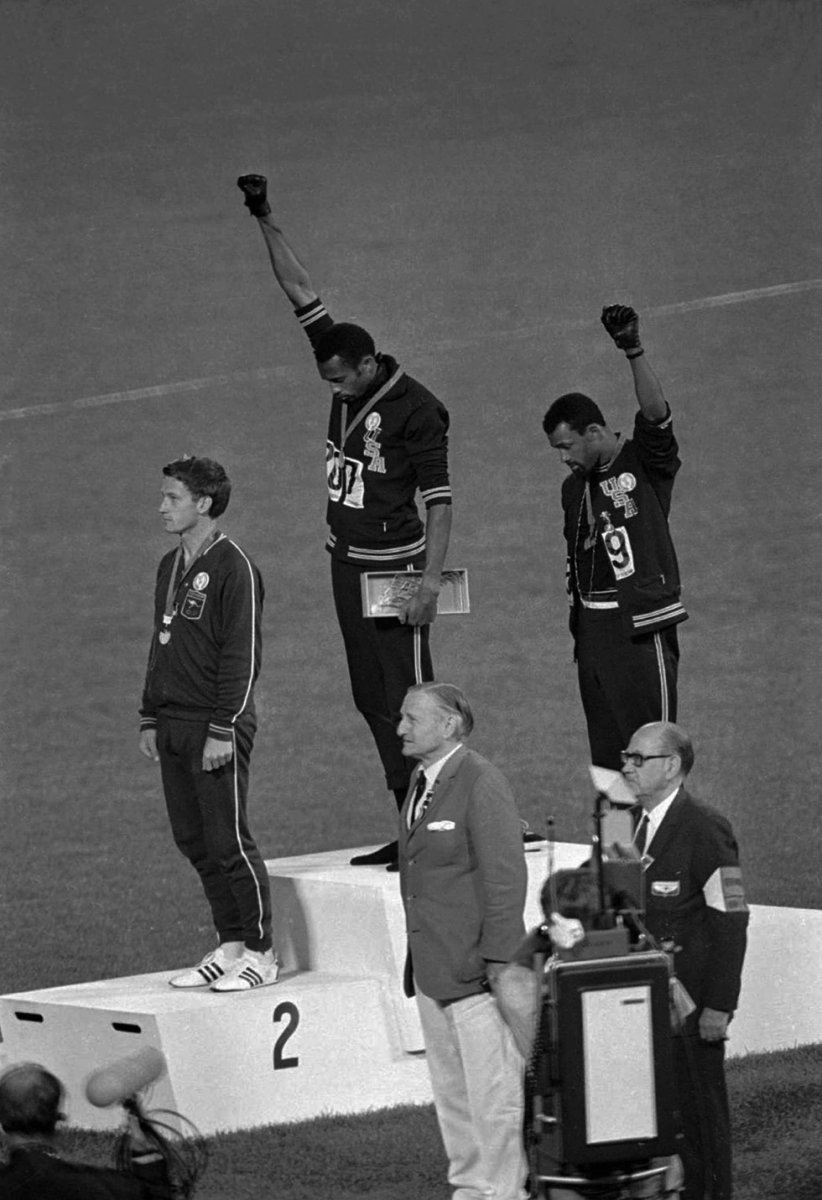

6. The 1968 Olympic 200m Final

Tommie Smith and John Carlos protesting at the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City.

After winning gold and bronze, respectively, in the 1968 200m dash at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City, American runners Tommie Smith and John Carlos each raised a single gloved fist as they stood on the winners’ podium during the playing of the national anthem. The Black Power fists were part of a larger set of symbolic gestures the two made on the podium, including removing their shoes in a gesture toward black poverty and wearing beads symbolic of the nation’s history of lynching. As with Ali, their protest was accorded less respect at the time than it has received subsequently. Both athletes were booed in the moment, kicked out of the Olympic village, and suspended from U.S. track and field.

Their actions were the outgrowth of what had been a larger attempt, led by athlete and activist Harry Edwards, to convince African-American athletes to boycott the ’68 Games altogether. Edwards’ “Olympic Project for Human Rights” advocated an Olympic boycott by black athletes unless a number of conditions were met, including increased hiring of black assistant coaches in U.S. track and field, the resignation of Avery Brundage as IOC president, and the return of the heavyweight title to Muhammad Ali. The boycott did not materialize, but Smith and Carlos each also wore OPHR patches on their track suits on the podium, as did white Australian silver medalist Peter Norman, who was sanctioned and vilified upon his return home.

7. 1969 College Football Protests

News clipping of Fred Milton, linebacker for Oregon State University.

A number of protests roiled the 1969 college football season, mostly centered on demands for political expression and/or personal respect made by black athletes. In February, Oregon State linebacker Fred Milton was suspended for violating team rules regarding facial hair. Milton’s choice of a neat Van Dyke – worn in the off season, no less – triggered a campus crisis featuring accusations of racism levelled by the OSU Black Student Union, campus boycotts, competing rallies for and against Milton’s right to choose his own style of grooming, and, ultimately, the exodus of 2/3 of OSU’s black students from campus.

At Wyoming, 14 black players were suspended over their decision to wear black armbands in connection with an upcoming game against BYU, as a protest against Mormon racial doctrines. Campus turmoil followed in Laramie as well. Similar incidents played out at Indiana and the University of Washington. In each case, public opinion in the short term tended to favor the right of coaches to impose traditional concepts of discipline and authority.

The biggest game of the season that year was the so-called “Game of the Century,” featuring the Texas Longhorns (9-0, #1 AP) against the Arkansas Razorbacks (9-0, #2 AP) in a nationally televised game presented by ABC as a sort of de facto national championship. President Richard Nixon was in attendance, as was Texas congressman George H.W. Bush and a number of other prominent politicians. Neither football program had yet fielded a black player, making it perhaps the last major de jure segregated event in the nation’s history.

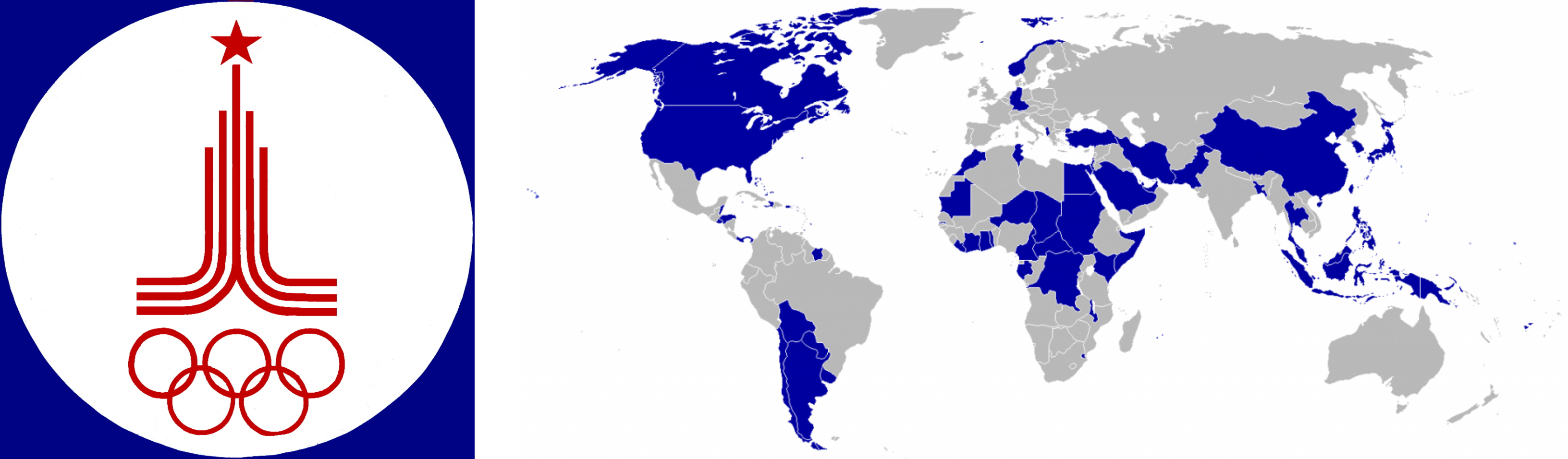

8. The 1980 Olympics

Logo of the 1980 Olympics in Moscow, USSR (left), and a map of countries boycotting the games in blue (right).

The 1980 Olympics in Moscow were the first awarded to a Communist nation. During the Cold War, the Soviet Union invested significant material and cultural resources into international athletic success, and as a result the Olympics evolved into a quadrennial Cold War soap opera of sorts for American TV viewers. After the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in late 1979, however, the Carter Administration sought a number of ways to protest the invasion, including an embargo of grain exports to the U.S.S.R. and the effort to convince other nations to join it in an embargo of the 1980 Games.

In the end, 65 countries declined to participate in the Games (though not all did so at the behest of the U.S.), and a number of other American allies such as Great Britain, France, and Australia sent athletes but protested in other ways, such as by avoiding the opening ceremonies or competing under a flag other than their national flag. The Soviets retaliated four years later by organizing an Eastern Bloc boycott of the 1984 Games in Los Angeles. The U.S. and Soviet Union did not compete again in the same summer Olympics until 1988 in Seoul, at which time Soviet troops were still stationed in Afghanistan.

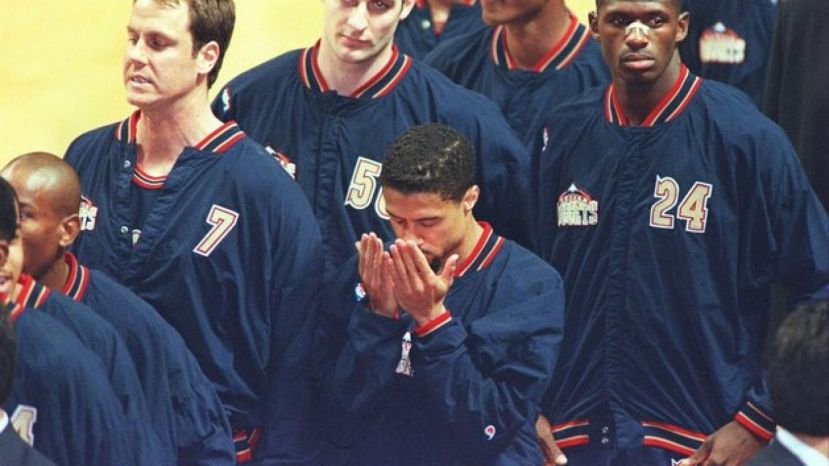

9. Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf and the National Anthem, 1995-96

Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf in prayer during the National Anthem, 1996.

Colin Kaepernick is not the first athlete to focus protest on the pregame rituals of flag and anthem. During the 1995-96 NBA season, Denver Nuggets guard Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf began forgoing the ritual of standing at attention for the anthem before games. Abdul-Rauf did not initially package this behavior as anything more than a private choice; for most of the season, in fact, he seems to have done so without anyone much noticing. He would stay in the locker room, or do extra pregame stretches rather than standing, or otherwise occupy himself on the floor without calling attention to himself.

Only in March was he asked about it by a reporter, at which time he explained that he viewed the flag as a symbol of racism and oppression and regarded standing for the anthem in conflict with his Muslim faith. At this point he was fined and suspended by the league. A few days later, with the support of the players’ union, Abdul-Rauf reached a compromise with the league whereby he agreed to stand during the anthem but not address the flag, choosing instead to pray downward silently. He did so for the rest of his time in the NBA.

10. WNBA, 2016 Onward

Members of the Minnesota Lynx wearing shirts protesting racism and police brutality.

While it hasn’t received the same level of media attention as protests in the NFL or NBA, players across the WNBA have engaged in a running series of demonstrations and protests connected to the Black Lives Matter movement, white supremacists in Charlottesville, Va., and/or the right of protest itself since at least July of 2016. These include a series of protests over the course of the recently concluded WNBA Finals. Unlike Kaepernick, who has yet to find another team, the vast majority of WNBA protesters remain employed as professional athletes.