The juxtaposition of laughter and tragedy in the Charlie Hebdo shootings earlier this month has sparked a feverish search for answers to how the gunmen came to be so angered by the cartoonists’ drawings that they decided to take up arms to stop the satire.

What many analysts have missed, however, is that the January 7th attack was by no means the first time that extremists have murdered humorists for their art.

|

| Algiers during Algerian Civil War |

Instead, for the last few decades in Algeria and elsewhere, radical organizations spurred on by political goals and a zealous reading of religious texts have been levelling their ire with deadly consequences at comedians whose work they have deemed to be blasphemous or opposed to their objectives.

During Algeria’s dark decade of civil war in the 1990s—which took more than 200,000 lives—militants from various armed groups claiming to represent a truer form of Islam killed three humorists—Saïd Mekbel, a satirical editorialist, Brahim Guerroui, a cartoonist, and Mohamed Dorbane, a columnist and caricaturist—and threatened numerous others comedians.

|

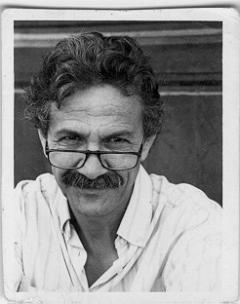

| Saïd Mekbel |

Perhaps the most well-known and beloved was the editorial writer Saïd Mekbel. His rapier sharp wit spared no one as he doled it out daily in the popular newspapers Alger Républicain and Le Matin. The “ghoul” and “J’ha’s nail,” as Mekbel signed, used his pen to pinpoint and exploit the absurdity of the country’s problems, especially its political system.

Islamists served as the butts of several of his jokes. Mekbel also made fun of the terrorist organizations claiming to represent the Islamic Salvation Front, the country’s largest then-defunct Islamist group that the military had kept from taking power in January 1992. He underscored as well what he viewed to be the rapacious and self-serving motivations of the Islamic Salvation Front’s leader, Abassi Madani. Mekbel joked that he had come to save Algeria as Zorro had rescued Mexico only that, unlike the cowled hero, Abassi put himself front and center at public events to garner more attention.

Mekbel even used his comicality to ridicule the violence against himself and his colleagues, depicting journalists as having to act like common criminals, scaling the walls of their own homes due to the threats that the rebels had made against them. The day after composing this essay in December 1994, Mekbel went out to lunch with a friend in a local neighborhood. Like many other journalists still in Algeria at the time, he had the habit of sitting facing the front door in the event that an attacker entered, a reflex that some media workers retain to this day. On that fateful afternoon, the gunman came in through the kitchen.

The essay that he had written about the pitiful existence of journalists living under terrorism appeared in newspapers that day only hours before his death. It would be republished in numerous Algerian papers over the next few days as devastated colleagues prepared for his funeral.

Guerroui was kidnapped and murdered in September 1995, while Dorbane died when a bomb that militants had placed near the offices of his newspaper exploded on February 11, 1996

Even for those Algerian comedians who survived what writer Mustapha Benfodil has termed “an intellectocide,” a killing spree that left hundreds of Algeria’s intelligentsia dead, fear of assaults against themselves and their families caused immeasurable suffering and insecurity, inciting many to seek refuge abroad.

| Ali Dilem |

But not only did the rebelling armies target humorists for assassination, surviving death lists that the militants had created in the mid-1990s show that they occasionally prioritized condemning humorists. The satirical writer Mekbel and his colleague Ali Dilem, a caricaturist, appeared frequently on these “hit parades,” the ironic name that those targeted gave the lists. At times, the rebel groups even marked Mekbel and Dilem as the numbers one and two to be murdered.

Their crime? Why kill the humorists?

According to propaganda tracts that the armed rebels printed, journalists including Dilem and Mekbel deserved to die for producing cartoons and writings they believed not only defied God and sowed discord among Muslims but supported an illegitimate and impious military regime in Algeria. Leaders of one major organization in the war responsible for killing intellectuals reportedly stated “Those who combat us with the pen will die by the sword.”

Yet, if the rebels were concerned about journalists collaborating with the Algerian state, it was investigative journalists rather than caricaturists and columnists who were the ones covering major events and therefore the most capable of manipulating security information for the state (which is, of course, not to say that they did such a thing or that they deserved to be murdered even if they had).

The placement of two comedic artists at the top of their killing lists makes clear that the insurgents prioritized attacking artists whose work resonated with the population and who, in their opinion, symbolically challenged their cause.

Algerian readers faithfully devoured Mekbel’s column and Dilem’s cartoons, with their playful way of ridiculing Islamist partisans, the armed insurgents, and other political figures.

What can these cases of threatened and murdered artists and writers in Algeria reveal for the post-January 7th, 2015 world?

There is no reason to believe that another country will soon experience the systematic terrorism against intellectuals that Algeria endured in the 1990s. Yet, the Charlie Hebdo attack along with the July 2012 murder of popular Somalian comedian Abdi Jeylani Malaq Marshale by al-Shabab fighters indicate that extremists may keep finding satirists a nuisance that they are willing to kill to get rid of.

Al-Shabab militants gunned down the noted Somalian radio personality and comic as he left work one night. Marshale had ridiculed the group in his routines and had received death threats on numerous occasions prior to his murder.

In the future, humorists and especially cartoonists might prove more likely than other media workers outside of combat zones to find themselves in terrorists’ sights.

As the cases of Mekbel, Guerroui, and Dorbane demonstrate, the murder of humorists by extremists is not a new phenomenon born in the 2000s at the moment when European caricaturists started drawing the Prophet Muhammad.

Indeed, these attacks against humorists have a long history and were not simply conditioned by cultural differences. In the Algerian case, the humorists were locals—not westerners—killed over their drawings and their jokes.