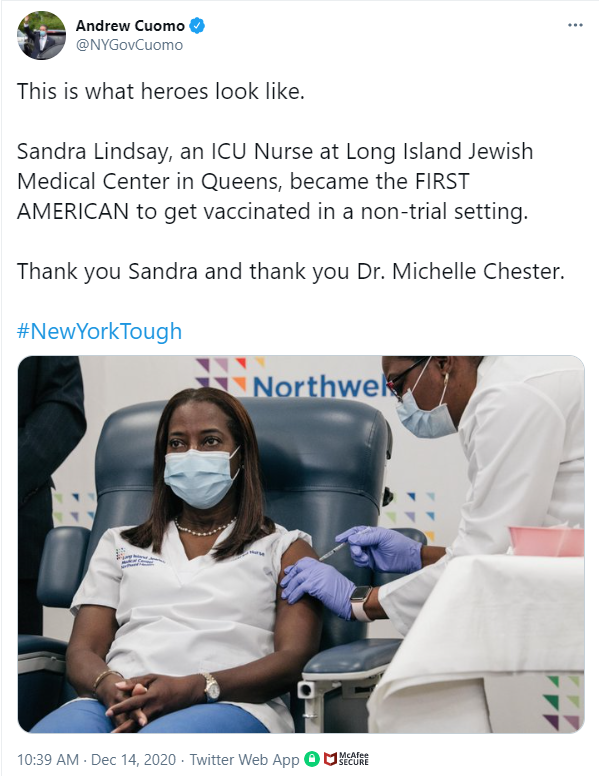

Sandra Lindsay, a Black, Jamaican intensive care nurse at Long Island Jewish Medical Center in New York became the first person in New York City, and in most news reports, the United States, to be inoculated with the COVID-19 vaccine on December 14, 2020. Lindsay’s vaccine shot was administered by a Black physician, Dr. Michelle Chester.

Given the virtual absence of Black medical personnel in the U.S. healthcare system, especially nurses, the mass circulation of this image and the optics of the two Black female health care workers appeared orchestrated. Governor Andrew Cuomo and the medical community praised Lindsay. She was a healthcare hero.

Lindsay was also a reminder of the ways in which ideas of race and the practice of medicine have a troubled history, with serious medical outcomes for the Black community.

The effects of racism on health are apparent in the roll-out of the COVID-19 vaccine. The racial disparities in access to the vaccine are stark, while there also exists a distrust of vaccinations among the Black community.

It is easy to pathologize Black peoples’ fears regarding COVID-19 vaccination as cultural, as many analysts are doing today. Given the history of medical atrocities perpetuated against Black people, however, it is more than likely that it is the people and medical establishment behind the vaccine, as opposed to the vaccine itself, that Black people are afraid of.

Nurse Eunice Rivers talks with test subjects of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, c. 1953.

For some members of the Black community, Lindsay conjured up recollections of Eunice Rivers, the public health nurse who acted as the intermediary between the Black men who participated in the Tuskegee Study (1932-1972) and the U.S. Public Health Service. The purpose of this infamous experiment was to study “untreated syphilis in the male Negro.”

A Black Twitter user asked, “Wasn’t it a nurse, a sister at that… that help[ed] gather [patients] for the Tuskegee Experiment”? Another intoned, “Eunice strikes again. But this time, many of us are aware what’s going on.”

The twitter users are correct. Rivers’ involvement in the Tuskegee experiment was extensive and, without her, it would not have been successful. She found subjects for the study and went as far as to drive them to Tuskegee for examinations. She assisted with assessments and some medical procedures and completed follow-up paperwork. When the men died, Rivers encouraged their families to allow Tuskegee Hospital to perform autopsies.

Eunice Rivers takes a blood sample from a test subject of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, c. 1953.

Rivers was not the only Black person involved (Dr. Robert Russo Morton, Tuskegee’s Institute’s principal and Dr. Eugene Dibble, medical director, for example) and other health care professionals “signed off” on the “experiment.” Still, she is often the face, and has borne the brunt, of the attention in relation to the experiment. Evoking Rivers’ complicated role in the Tuskegee experience in response to Lindsay is understandable.

Historically, across the African diaspora, Black women were instrumental in the provision of health care. Black health care workers, whether formally or informally trained, were trusted by members of Black communities.

Nurse Rivers was no exception. She developed amicable relationships with the men and their families, captured in the Emmy award winning television movie “Miss Evers’ Boys”. Sadly, the Tuskegee experiment is one of several examples that has led to Black people’s distrust of the medical establishment.

To understand this distrust, one must focus on the historical mistreatment of Black people. One cannot argue that it is some sort of shared cultural trait and ignore the racist structures that have continually dehumanized Black people.

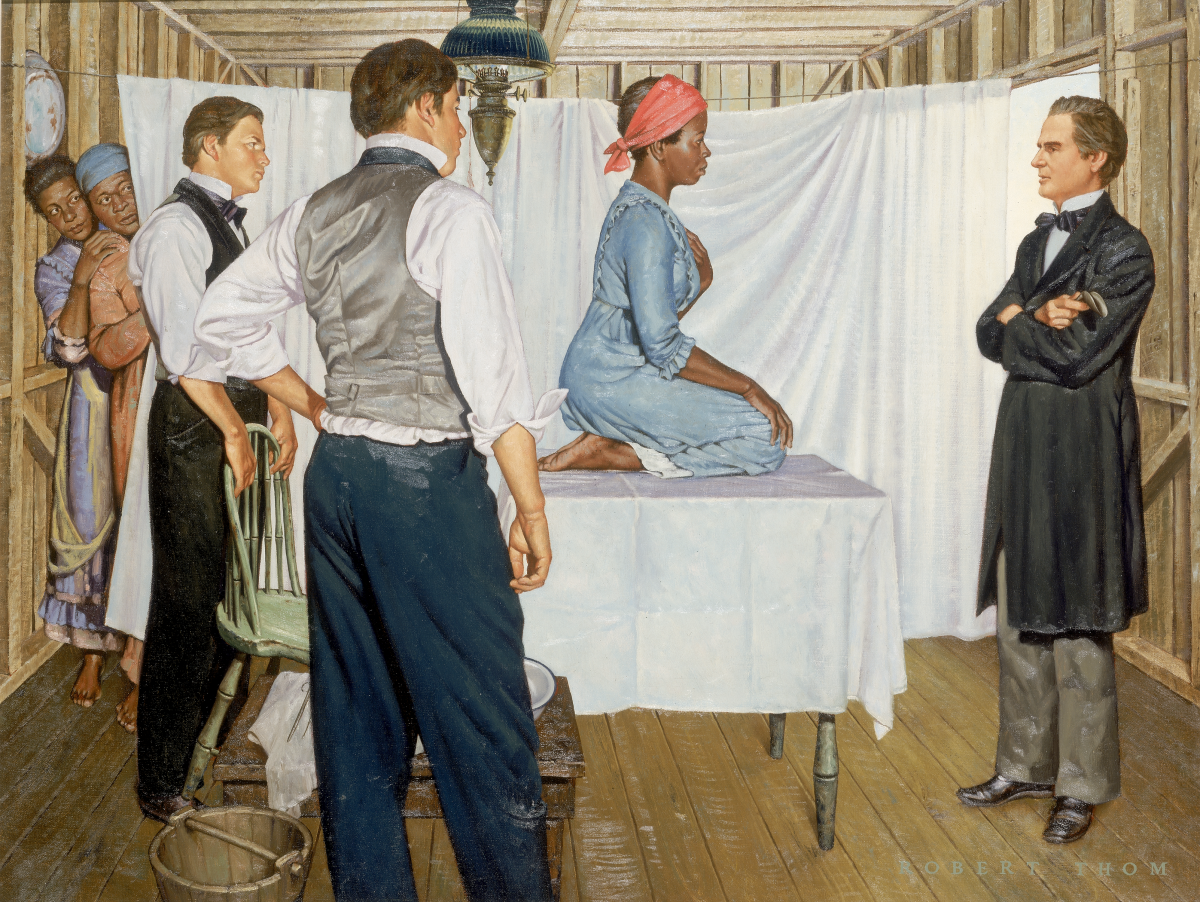

For example, Anarcha, Besty, and Lucy are the names of enslaved women whom Marion Sims, the father of gynecology, experimented on. He performed surgeries without anesthesia because of a widely held belief that Blacks had a higher tolerance for pain.

Then there is Henrietta Lacks, whose cancer cells (known as HeLa cells) were taken without her consent and studied in laboratories, and the forced sterilization of Black women and teenagers in North Carolina at roughly the same time as the Tuskegee experiment. These are a few examples of the liberties that the medical establishment has taken with Black bodies.

But we should not believe that health inequities are a now a thing of the past. Research has shown that graduating medical students hold views similar to Sims regarding Black people and pain.

And it isn’t primarily poor people who are affected by racism, as many people assume. Race, gender, and class intersect on the persistent health inequities experienced by middle-class Black women and their encounters with physicians.

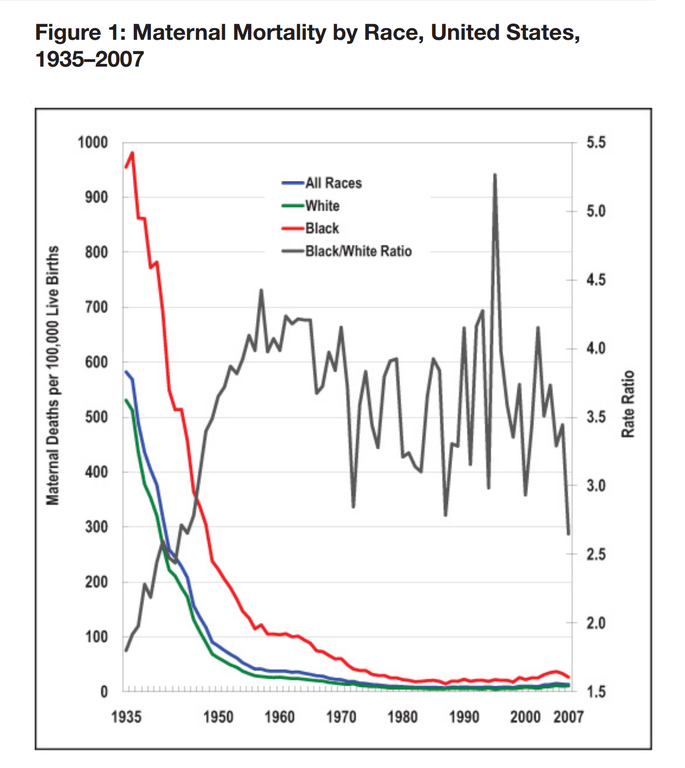

A graph showing maternal mortality by race in the United States from 1935 to 2007.

Black women, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “are two to three times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than white women.” Compared to white women with a high school education, Black women with college degrees have higher infant mortality rates.

The very rich and famous are not exempted either. Tennis player, Serena Williams, has written about her horrifying birthing experience. Williams’ history of blood clots and other health issues resulted in her spending six weeks in the hospital following the birth of her daughter. Her traumatic experience became a high-profile testament to a medical system that is designed to fail Black women. Fortunately, Williams had the resources to avoid becoming another statistic.

The unequal experience that Black people have experienced during the COVID pandemic was given a face late in 2020 when a video made by Dr. Susan Moore went viral.

A physician and a COVID-19 patient, Moore, posted a Facebook video where she described the racist mistreatment she experienced at the hands of medical personnel at an Indiana Hospital. Moore knew well that the system has little regard for Black lives. “This is how Black people get killed when you send them home and they don’t know how to fight for themselves,” she stated.

Moore was fighting for herself, but her complaints of pain were dismissed by the physician. According to Moore, he made her feel as if she “was a drug addict,” adding, “if I was white, I wouldn’t have to go through that.” Within a few days after being discharged from the hospital, Moore died from COVID complications. Her death is a stark and painful reminder of the disposability of Black lives and serves as additional evidence of medical racism.

The mistreatment and exploitation experienced by African Americans in the name of scientific research helps account for their refusal to be inoculated for COVID-19, but we should also not disregard how history is being made in the present.

We need more than cursory acknowledgment to histories of abuse and neglect. As Black people continue to die disproportionately from the coronavirus, Sandra Lindsay and other Black medical personnel cannot be the panacea.

The burden of undoing decades of racism and inequality, which has been and continues to be embedded in the American medical system, must be a shared one.