As you ride the Number 22 bus towards Ocean Terminal, you watch the city of Edinburgh fade away as its port neighborhood of Leith replaces it. The wealthy Georgian facades of New Town transform into charity shops, pubs, Indian restaurants, and the occasional Tesco Express. When you reach the end of the long Leith Walk, you are greeted by Queen Victoria proudly watching over a small pedestrian square that includes a Poundland and Boots.

The Shore, the main street of Leith, next to the Water of Leith.

The bus then turns off the Walk and onto Henderson Street, a road that barely fits a large double-decker bus. On your right, you will encounter the upscale whiskey house, complete with nineteenth-century stone walls that feature the beautifully carved Porter’s Stone, which immortalizes Leith’s warehouse roots.

Yet, if you look to the left, you’re met with the surprising sight of the Banana Flats, a brutalist-style building named for the strange curved nature of its façade (officially known as Cables Wynd House). Forty years ago, these flats were known for harboring opioid users. Today, they are a Category A listed historic monument that still houses hundreds of residents.

Cables Wynd House, better known as the Banana Flats.

There is a sense of irony in the decision to list the building. The Banana Flats once embodied everything that Edinburgh felt was wrong with Leith. They were overcrowded, riddled with drugs, and a significant eyesore. With their place on Scotland’s list of historic sites, they now embody what Edinburgh wishes to remember about Leith.

Situated on the Firth of Forth and acting as Edinburgh’s outlet to the North Sea, Leith is a neighborhood of juxtapositions and harsh realities that has stood as the symbolic and literal entrance into Edinburgh for hundreds of years.

The first evidence of maritime industry comes from the 12th century but it gained notoriety throughout the 14th and 15th centuries as a port in the Hanseatic League. As Edinburgh’s port, it saw many royal figures pass through its gates. Mary, Queen of Scots, Charles I, and George VI all entered the capital city through Leith during their reigns.

The Porter’s Stone, a reproduction of which now hangs in its original location in Leith (left); The Merchant Navy Memorial on the old dry dock commemorating Leith’s maritime history (right).

Despite its royal connections, Leith has always been a place of laborers. From the port itself, to the shipbuilding industry, whaling, and warehouses, the culture of the neighborhood is steeped in its labor roots. Today, the memory of that history is told through public art, historic preservation, and a vibrant community.

The most significant change for Leith, and what many see as the beginning of its decline, came in 1920 when Edinburgh absorbed the once autonomous city into its jurisdiction. Edinburgh relied on Leith as one of its leading economic and industrial centers after the merger. It was the port that expedited economic flow into Edinburgh and connected the city with the world.

The old railroad bridge that ran parallel to Leith’s docks, a lasting symbol of Leith’s industrial past.

The merger came with significant opposition from the citizens of Leith who voted 26,810 to 4,340 against the amalgamation. This decision is still felt profoundly in Leith, and the neighborhood continues to assert its independent spirit, namely through t-shirts that proudly display “The People’s Republic of Leith” across the chest.

Leith also became the entrance for substances that would plague Scotland to this day. The first recorded opioids in Scotland came through Leith in the late 17th century. They persisted in the culture of the middle class through the 19th century and remained a mainstay of Leith in the twentieth century.

Whaling harpoon on the Water of Leith: another reminder of Leith’s industrial past.

The post-World War II era brought more trouble to Leith as most of the docks closed. So did the shipbuilding yards in the early 1980s, all of which left thousands out of work. As heroin became the drug of choice for many former dock workers and shipbuilders, the rapid decline of manufacturing and high unemployment earned Leith its rough reputation among the neighborhoods of Edinburgh.

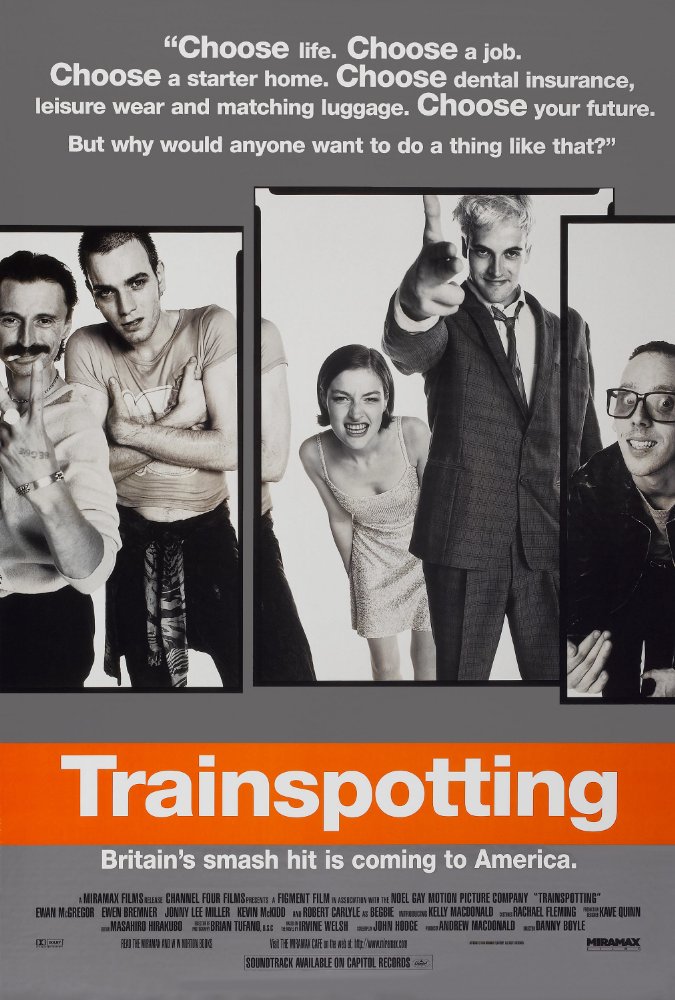

This painful part of Leith’s history was immortalized in Irvine Welsh’s 1993 book Trainspotting (and later in the 1996 movie starring Ewan McGregor). This portion of Leith’s past is not entirely gone, however.

Scotland still has the highest drug-related death rate in Europe. According to the National Records of Scotland, 1,187 people in Scotland died from drug-related causes in 2018 alone. In a population of just 5.4 million, that is a significant number. Most of the deaths are from those 35 years and older, or what is called the “Trainspotting Generation.”

Between 1981 and 1986, Edinburgh’s City Council stepped in to implement the “Leith Project.” It sought to clean up The Shore (the main street of Leith), build affordable housing to alleviate overcrowding, and promote small businesses in the many empty storefronts.

Ironically, Edinburgh had undertaken a similar project 20 years earlier when the City Council built the Banana Flats. They were meant to alleviate overcrowding and promote a new vision of Leith, but the Flats ended up as the symbolic epicenter of Leith’s troubles.

While the Leith Project was successful in its goals, it had the inadvertent effect of promoting gentrification. Today one can find Michelin-starred restaurants, swanky pubs, tourist attractions such as the Royal Yacht Britannia, and a massive shopping mall. The Scottish Government also built a large bloc of administrative offices to bring civil service jobs to the area.

The other side of The Shore, depicting the Maritime House, third from the left. The former headquarters of the National Seamen’s Union are now flats.

Although this project diversified the economy and took care of the overcrowding problem, it pushed house values up and made way for financially unattainable options in the neighborhood. Between 1985 and 1990, the years immediately after the Leith Project, housing prices rose 40%. Today you can expect to spend around £200,000 on a one-bedroom flat in Leith, compared to the £45,000 you would have paid in 2001.

While Leith has a distinct maritime, industrial, and working-class culture, when you visit the neighborhood today, the only reminders of that period are large ships in the distance and occasional memorials for workers or seafarers. Sometimes you can spot a wrought-iron ship, Leith’s symbol, on windows or doors.

The ship, Leith’s symbol, is found throughout the neighborhood on windows, doors, and other facades.

Some organizations seek to highlight Leith’s time as a working port and shipbuilding area. LeithLate, a grassroots visual arts organization supported by the City Council, sponsors public art in the way of murals. These murals feature local artists and their interpretations of the neighborhood’s past.

Historic Environment Scotland (HES) has also turned its attention to preserving Leith’s distinct history by placing industrial sites and housing units on their historic sites list. The latest of these include the Banana Flats, which received status in 2017.

Teuchters Landing Freehouse, a restaurant in the old Edinburgh-Aberdeen Ferry waiting room and a popular hangout amongst Leith dwellers.

Anyone visiting Edinburgh should make a note of the contrasts found along the streets. These tell a story of labor, the sea, gentrification, and of hardships and Edinburgh’s vision for the future. While you walk along the Water of Leith, pull up “Sunshine on Leith” by The Proclaimers and dwell on what this neighborhood means to the past of Scotland’s capital.

[All photos by author, unless otherwise indicated]