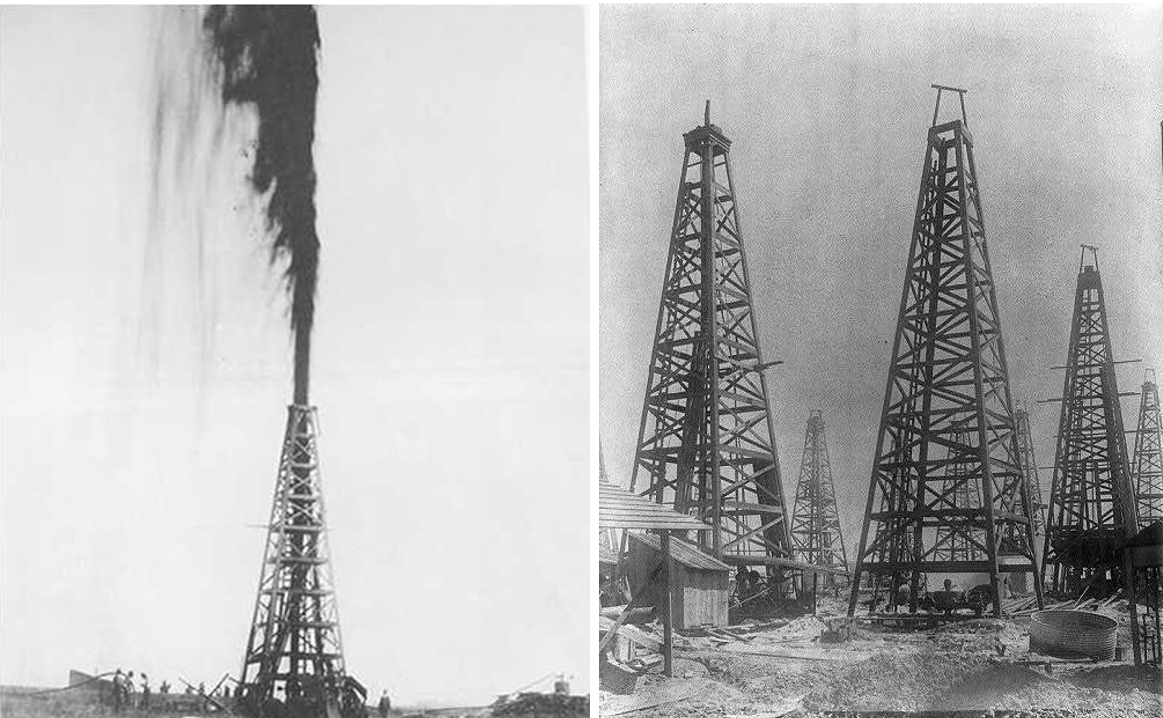

Think about some of the iconic images that you would choose to represent Texas – ten-gallon hats, longhorn cattle, armadillos and the Alamo would surely all make the cut. But certainly, many would add a “nodding donkey” – as oil derricks are sometimes called – to that list. Texas and energy have been tied together since the start of the twentieth century, when oil was discovered close to Houston in Spindletop.

The Lucas Gusher at Spindletop Hill in Texas, 1901 (left). Oil well field near Port Arthur, Texas, 1901 (right).

In February 2021, though, Americans were stunned by dramatic images from Texas of a severe cold snap that left icicles hanging off ceiling fans and stories of families going days without power as the Lone Star State’s electricity system faltered in the middle of the emergency.

Adding insult to injury, sky-high power bills greeted Texans as the market logic of supply and demand kicked in. The cognitive dissonance of the lights going out in Texas was as big as the state itself. How could this be possible in the country’s undisputed energy capital?

Of course, there were many factors at work in the Texas energy crisis – climate change chief among them. However, at least some of the blame can go to the now-disgraced energy company, Enron, and its misuse of long-held American attitudes towards corporate power.

Ken Lay in his 2004 mugshot (left). The logo of Enron (right).

Nowadays, the mention of Enron and its leader, Ken Lay, conjures images of the financial slight of hand that ruined the company in 2001. But before that point, both Ken Lay and Enron were at the vanguard of promoting energy deregulation around the country.

If you were an Enron employee and opened up an issue of the employee magazine, Enron Business, in, say, 1996, you would find articles touting the promise of electricity deregulation. As Enron put it, the company was working to “bring competition to the U.S. retail market for electricity, one of the last great monopolies.”

In a letter to the company’s shareholders that same year, the company predicted that with the electricity deregulation it was pursuing around the country, “monopolies” would be “broken up” and markets would be “liberated.” With such rhetoric, Enron’s government affairs and marketing teams were tapping into a deep current in American culture.

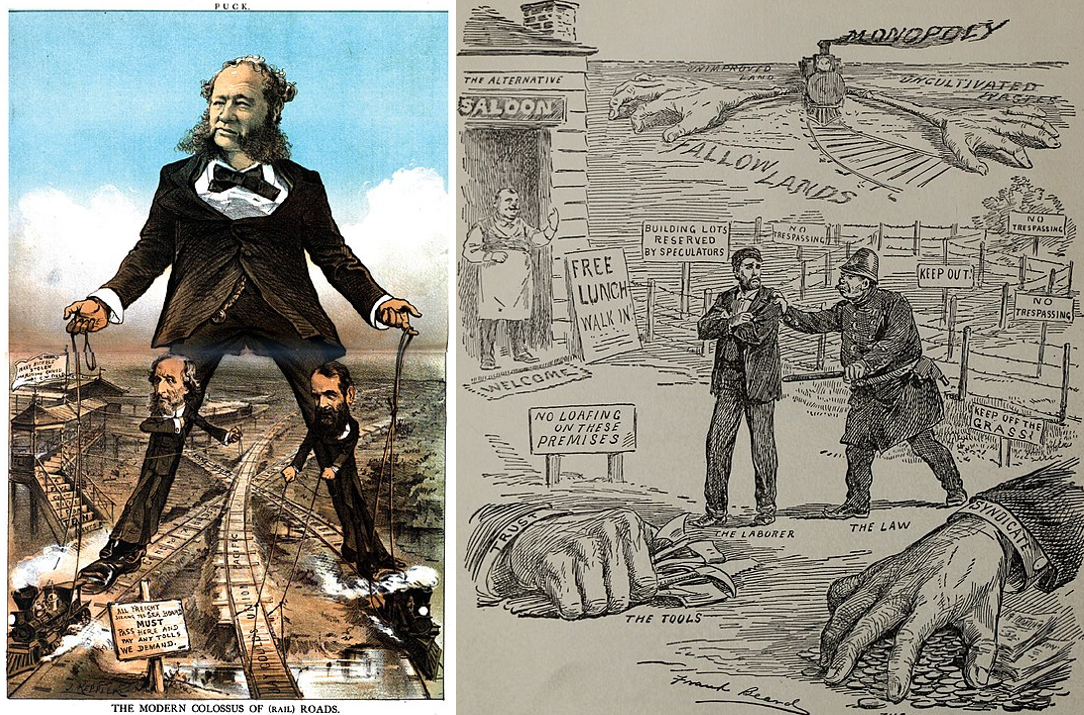

As the historian Richard White tells us, monopoly was the “key word in the reform vocabulary” in the late nineteenth century’s Gilded Age. After all, these decades produced powerful corporations like Standard Oil and Carnegie Steel that dominated their respective industries, threatening both smaller businesses and consumers.

An 1879 cartoon from Puck magazine depicts powerful businessmen controlling the railroad system under a monopoly (left). A 1902 anti-monopoly cartoon showing the challenges that monopolies may create for workers (right).

Since that time, Americans have regarded the word “monopoly” as a stand-in for just about every corporate ill. The word’s staying power suggests that Americans remain wary of an undemocratic concentration of power in the hands of private interests.

But Enron’s use of the word at the end of the twentieth century is more complicated. In fact, the system that Lay and others at Enron denounced had actually been put in place to prevent the further concentration of economic power that Gilded Age monopolies represented.

To combat the “Power Trust” – vertically integrated monopolies that characterized energy companies in the 1920s – President Franklin Roosevelt signed the Public Utilities Holding Company Act (PUHCA) in 1935. PUCHA split the power business into different – and heavily regulated – segments.

In the decades that followed, local monopolies supplied power for individual American households. While these companies did not face the pressures of a competitive market, they were kept in government control, which determined the rates companies could charge.

President George H. W. Bush signs the Energy Policy Act of 1992.

However, regulatory frameworks aren’t set in stone, and in the 1970s and 1980s, economists, activists, and politicians all began to explore deregulation in a number of different industries, including energy. When President George H.W. Bush signed the Energy Policy Act into law in 1992, this ethos of deregulation was well established across the American economy.

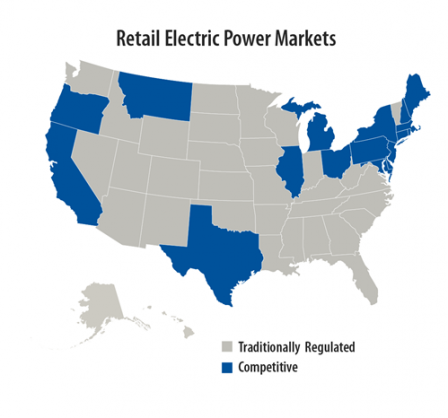

Among its provisions, the law directed the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) to look into the possibility of allowing “open access” to power transmission lines. The system that PUHCA created, in other words, was now up for grabs. Still, electricity deregulation was not going to happen all at once. Instead, interested parties were going to pursue this state-by-state.

For example, Enron’s government affairs team considered changes to Ohio’s electricity industry to be another victory, since it was as the “third largest energy consuming state.” It was, to hear the company tell it, another victory over “monopolistic power.” “Ohio’s monopoly electric utilities,” an Enron Business article claimed, “had exerted so much influence” that they had threatened to keep companies like Enron out of the state for years.

A map of the United States showing where the energy market is deregulated as of 2020 in blue.

Texas, though, was perhaps Enron’s biggest prize in this campaign.

Throughout the 1990s, Enron’s leader, Ken Lay, leaned into the effort, drawing on his personal ties with the George W. Bush, who was then the Lone Star State’s governor. In letter after letter, Lay tried to convince Bush to sign pending legislation to open the state’s power grid to deregulation.

Enron executives considered it a big win when Bush finally signed Senate Bill 7 on June 18, 1999. Noting that Texas was just the latest state to push for deregulation, one Enron Business story crowed, “Governor Bush’s action was one more step on the march to pry open an industry that has been protected from competition for over a century.”

What’s more, Texas clearly played a special roll in this push for deregulation. As one Enron executive put it, not only was Texas the company’s “home state,” but “more electrons” were “sold” there than anywhere else in the country.

In Texas, electricity deregulation swapped PUHCA’s system for retail competition among investor-owned utilities to begin in 2002. This new system – supposedly rid of untrustworthy monopolies – set the stage for those outrageous power bills that Texans had to deal with in February 2021.

Two satellite images of Houston, Texas on February 7 (left) before the winter storm and on Feb 16 (right) after the storm. The dark patches in the latter image show the areas experiencing power outages.

Reactions to the mess have varied.

Rick Perry, the state’s former governor, declared that “Texans would be without electricity for longer than three days to keep the federal government out of their business.” Others have offered more thoughtful reflections, and the wisdom of electricity deregulation is getting another look.

As we search for lessons from this episode, we should remember Enron’s role and the problematic ways that companies can use words like “monopoly” to pursue their own self-interests.