Today’s national political conventions are mostly infomercials. The nominee has long since been determined by state primaries and caucuses, and his or her running mate has already been selected. Weird things still happen from time to time, but for the most part conventions now function primarily as speech delivery vectors.

But presidential nominating conventions of the past were once dispositive—nominees were determined at the convention by the delegates, and not always smoothly. Here are between nine and twelve Presidential nominating conventions (depending on how you score the Democrats in 1860) at which the outcome wasn’t clear at the outset.

Anti-Masons 1831

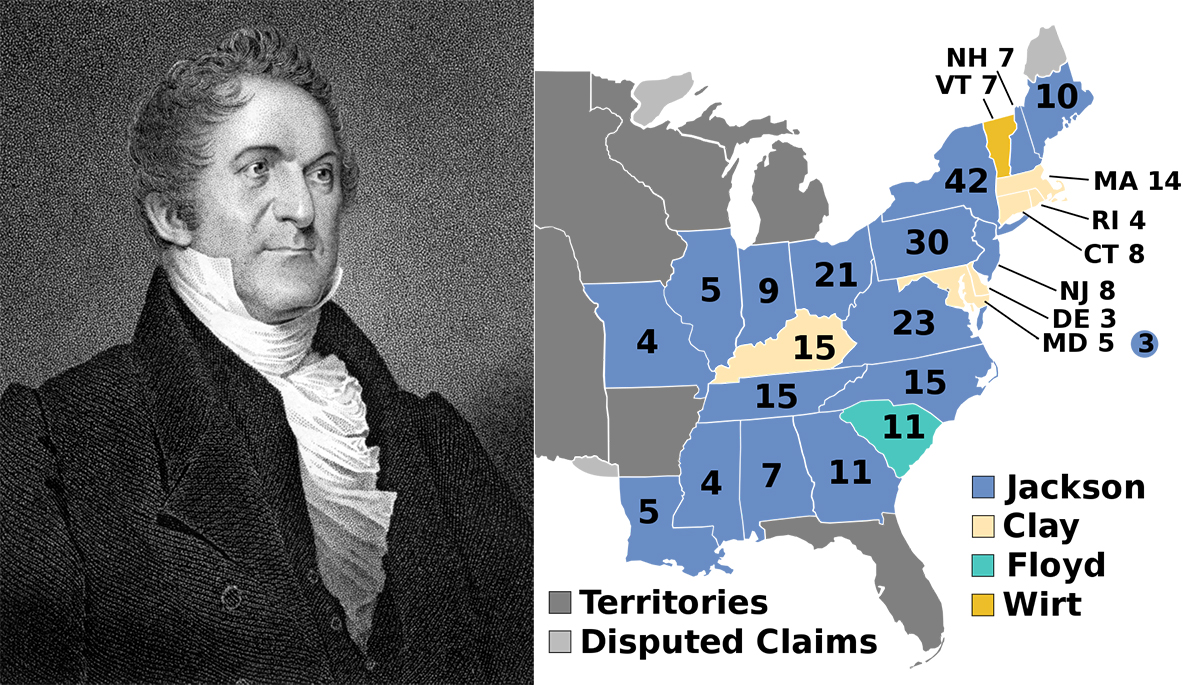

William Wirt, the Anti-Masonic presidential candidate in 1832 (left); map of the results of the presidential election of 1832, showing the seven electoral votes won by Wirt (right).

Political conventions began appearing at the state level in the early 1800s, but the first American political party to select a Presidential nominee by convening openly was the Anti-Masonic Party in 1831. The Anti-Masons were a so-called “third party” rooted in upstate New York and parts of New England. In the late 1820s and early 1830s, they sought to spin opposition to allegedly conspiratorial Freemasonry into a broader anti-Jacksonian political movement.

They had a problem: many plausible national opponents of President Jackson were themselves current or former Freemasons, including the man they ultimately nominated, William Wirt. “I have, indeed, thought very little about it for thirty years,” said Wirt of Freemasonry in his acceptance letter to the convention, “…. and so little consequence did I attach to it, that whenever Masonry has been occasionally introduced as a subject of conversation, I have felt more disposed to smile than to frown.” Wirt nevertheless won seven electoral votes.

Democrats 1844

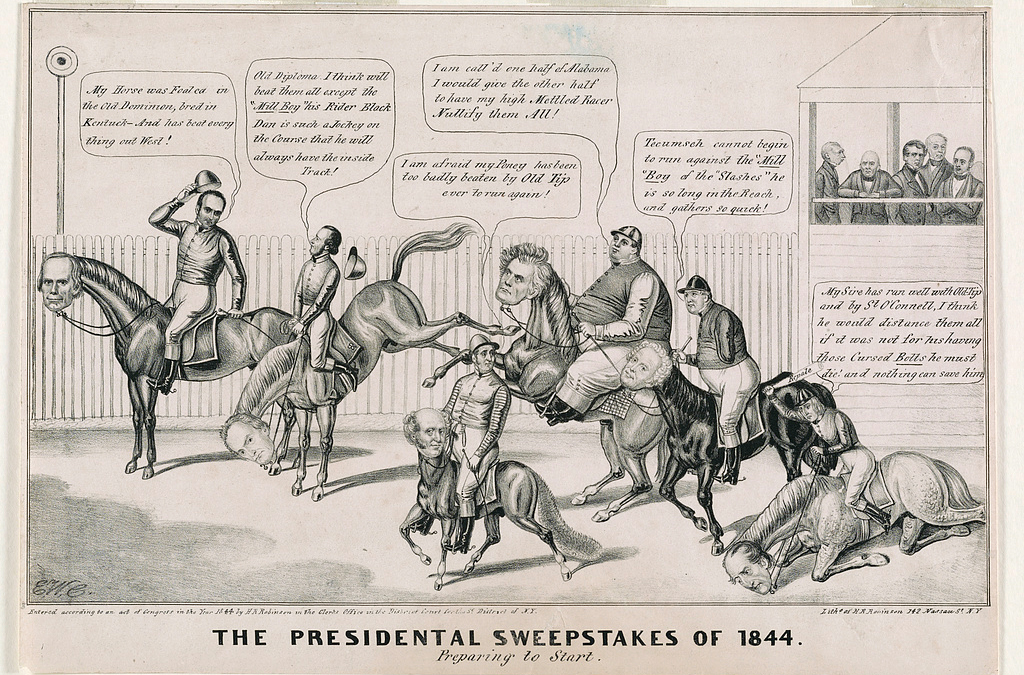

Most observers expected former President Martin Van Buren to earn the Democratic nomination in 1844, as he had in 1836 and 1840. A majority of delegates to the convention in Baltimore, in fact, had already pledged to vote for him before arriving.

His longstanding opposition to the annexation of Texas, however, made him unacceptable to many southerners and expansionists. They managed to stop him by passing a convention rule requiring the nominee get two-thirds of the vote rather than a simple majority. Though he held his majority on the first ballot, Van Buren could not reach two-thirds; for seven more ballots neither could anyone else.

The convention eventually settled on former Speaker of the House and Tennessee governor James K. Polk, the first-ever “dark horse” candidate: unheralded before the convention began, acceptable to all factions of the party without thrilling any.

Polk solved the party’s Texas problem by offering regionally balanced belligerence: a maximalist policy on Texas annexation, combined with a maximalist policy on expansion into the Pacific Northwest. He won the Presidency in part by threatening war with Great Britain over the boundary of Oregon Country. Once elected, Polk’s Texas policy triggered a war which led to American annexation of half of Mexico. Meanwhile, he cut a sensible deal on Oregon. The two-thirds rule remained in effect at Democratic conventions until 1936, often functioning as a sectional veto.

Democrats, Plural, 1860

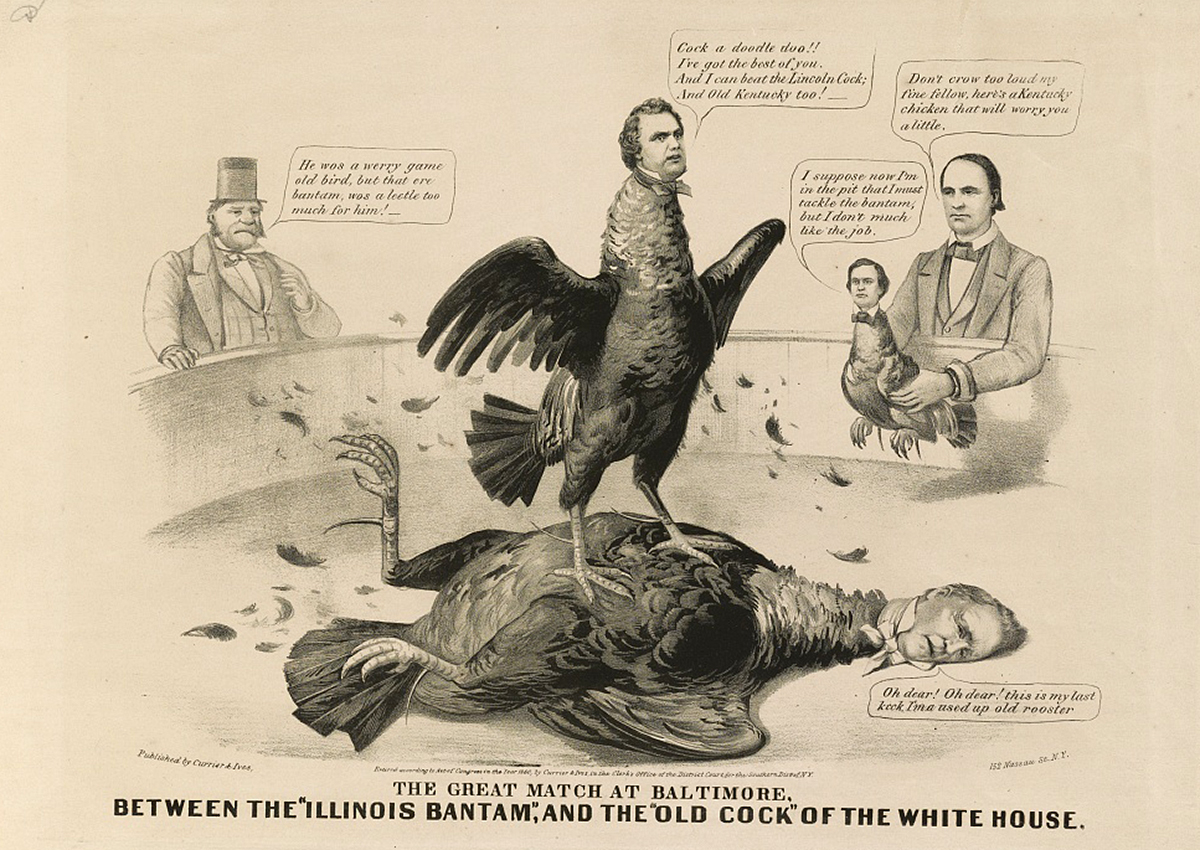

As, for example, it did in 1860. The continental expansion spurred by Polk and his successors had only intensified the sectional crisis, as national institutions of all kinds began cracking over the question of slavery in newly annexed territories. Stephen Douglas of Illinois emerged as one of the most successful national politicians of the 1850s by staking out a compromise position on the issue: “popular sovereignty.” Permit territorial settlers, sometime in the future, to determine the status of slavery themselves.

By 1860, however, this was insufficient for southern Democrats, who demanded pro-slavery positions in all situations. At the initial Democratic convention in Charleston, SC, 50 pro-slavery delegates walked out of the convention after failing to stop a popular sovereignty plank. The remaining delegates repeatedly gave Douglas a majority but could not, after 57 ballots, muster 2/3. The convention adjourned without a nominee.

A second attempt to convene in Baltimore six weeks later also broke down, resulting in regional schism: a mostly northern rump convention nominated Douglas, and a southern one nominated John Breckenridge. The split permitted Abraham Lincoln to win a majority of the Electoral College in a four-way race by winning all of the free state electoral votes and no slave state electoral votes. Secession followed.

Democrats 1896

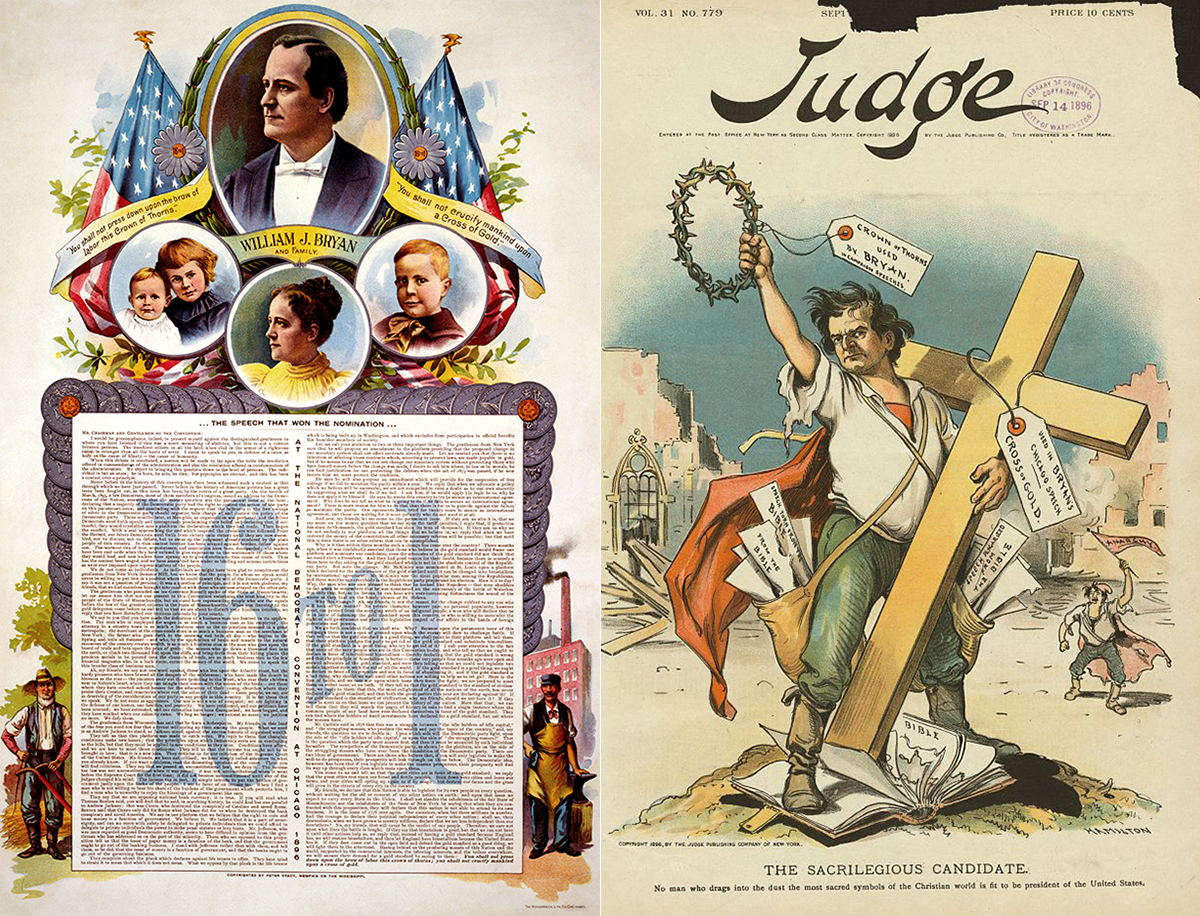

An 1896 campaign poster for William Jennings Bryan showing the full text of his "Cross of Gold" speech (left); the September 14th, 1896 cover of Judge Magazine, which assailed Bryan as "the sacrilegious candidate." (right).

People often overestimate the importance of speechmaking to political success, but in 1896 William Jennings Bryan really did gain a lifetime of influence over the Democratic Party by delivering one electrifying address at the party's convention: the legendary “Cross of Gold” speech.

Democrats in 1896 were riven over the issue of whether the value of American money should be pegged solely to gold, or gold and silver jointly. Bryan at the time was a 36-year old former Congressman from Nebraska with no particularly obvious path to higher office. He nevertheless thrilled the convention by comparing the gold standard to the Crucifixion: “You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns,” he exclaimed, miming its placement on his own head. “You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold!”

Bryan won the nomination on the fifth ballot, and remains the youngest person ever nominated President by a major party. He won the nomination twice more, in fact, in 1900 and 1908, and played kingmaker at several other Democratic conventions, despite never holding any elective office at any level after 1895.

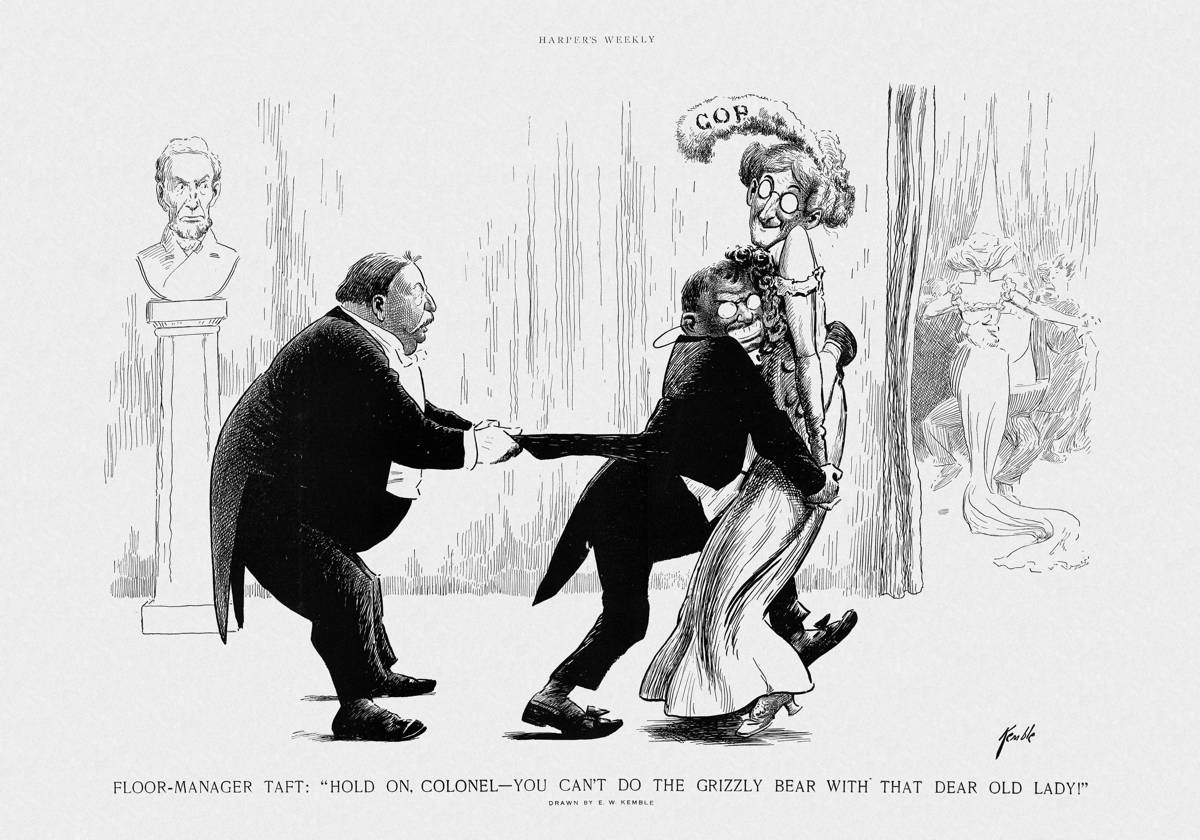

Republicans 1912

The outcome of some conventions depended more on how delegates were chosen than on whom the delegates chose. In 1912, former President Theodore Roosevelt attempted to take the Republican nomination away from his own hand-picked successor, William Howard Taft. For the first time that year, delegates from some states were chosen in open primaries rather than by state-level conventions, giving Roosevelt the opportunity to prove his popularity with rank-and-file Republican voters. Roosevelt won 290 delegates in the fourteen primaries, compared to 124 for Taft.

Taft nevertheless approached the convention with a presumptive nominating majority due to his control over delegate selection in non-primary states. Roosevelt’s only chance was to challenge the delegates themselves. In the run-up to the convention, the Republican National Committee adjudicated disputes over the legitimacy of 254 presumptive seats at the convention, most of them Taft delegates challenged by pro-Roosevelt forces.

But Taft controlled that process, too, and only 19 of the disputed seats were awarded to Roosevelt partisans. Roosevelt made one last effort to shake delegates loose on the floor of the convention by appearing in person and delivering an impassioned speech in favor of a series of progressive reforms, but despite the uproar this caused, Taft was nominated on the first ballot. Roosevelt responded by mounting a third-party campaign in which he managed to come in second, making Taft the worst-performing re-nominated incumbent in Presidential history.

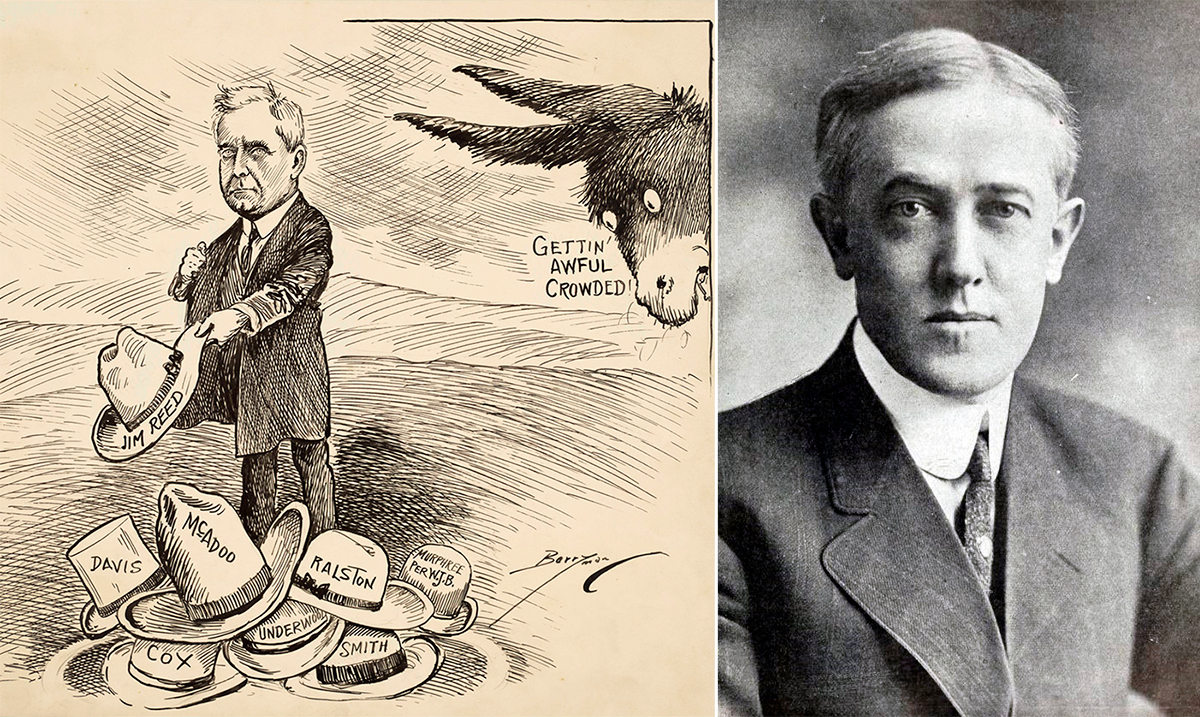

Democrats 1924

A 1924 political cartoon showing another Democratic Presidential candidate "throwing his hat in the ring" as a donkey comments worriedly on the size of the field (left); John W. Davis, the eventual Democratic nominee (right).

Most party platform debates go unremembered, but such was not the case in 1924, the first year the national conventions were broadcast live on radio.

The Democrats were deeply divided on a host of cultural issues symbolized by the emergence of the second Ku Klux Klan. The party’s urban wing was ethnically diverse, heavily Catholic, and anti-Prohibitionist; its rural and Southern delegates were overwhelmingly nativist, chauvinistically Protestant, and supported Prohibition. It therefore took them over five hours of pandemonium-inducing debate, all of it broadcast live on radio on a Saturday night, to determine whether the party platform should denounce the Klan. Anti-Klan forces lost, by a single vote.

The Klan vote presaged deadlock on the nomination itself. Prohibitionist and pro-Klan delegates mostly favored California Senator and former Secretary of the Treasury William McAdoo. Anti-Klan forces supported Al Smith, the Irish Catholic governor of New York. For 99 ballots, these two candidates finished first and second without either of them breaking 50%, never mind the 2/3 actually needed to win.

Each roll call began the same way, with Alabama governor William Brandon announcing in a thick Southern drawl, “Alabama casts 24 votes for Oscar W. Underwood!” By the second week of balloting, the entire convention—and much of the nation listening on the radio—joined in unison each time. Not until ballot 103 did both Smith and McAdoo stand down, permitting the nomination of John W. Davis of West Virginia. Fifty-eight different candidates received at least one vote at some point during the balloting.

Republicans 1940

Wendell Willkie in 1940 (left); a 1940 campaign button opposing President Franklin D. Roosevelt's third term (right).

During the 1940 primary season, the three highest-polling Republican candidates—Robert Taft of Ohio, Thomas Dewey of New York, and Arthur Vandenberg of Michigan—all opposed American intervention in European affairs. Then, between the end of the primaries in May and the beginning of the convention on June 24, Paris fell to the Nazis and party leaders became determined to find an internationalist nominee.

They had to reach well outside the usual pool of Republican candidates to find one, all the way to Wendell Willkie, a power company executive who had never run for office at any level and had been registered as a Democrat as late as the fall of 1939. But he had long been critical of the New Deal’s reorganization of the utility industry and he had long supported American aid to the Allies, and that was enough for Republican internationalists determined to prevent the nomination of Taft.

This convention was also the first broadcast live on television, though there were as yet only a few thousand TVs within range of the three stations broadcasting.

Democrats 1968

Television had a much larger impact on the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago, a year during which televised social chaos spread around the world. Delegates arrived in Chicago riven by divisions over the Vietnam War, civil rights, and how to respond to the widespread unrest triggered by the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy (who had been running for the nomination and gained 393.5 pledged delegates before his death).

Antiwar protesters also arrived in Chicago determined to publicize their cause through a combination of peaceful protest and satirical political spectacle, knowing full well that the Chicago police were likely to respond to protests with violence.

The chaos peaked on the third night of the convention, as television viewers watched riot police attempt to clear protesters from Grant Park with truncheons and tear gas as Connecticut Senator Abraham Ribicoff placed Senator George McGovern’s name in nomination: “And with George McGovern as President of the United States, we wouldn’t have to have Gestapo tactics in the streets of Chicago!”

The chaos figured prominently in Richard Nixon’s successful TV advertising against eventual nominee Hubert Humphrey.

Democrats 1972

While the top-line result was never really in question—George McGovern won on the first ballot after a procedural attempt to deny him the necessary delegates failed—the 1972 Democratic convention in Miami was nevertheless chaotic in effect, and probably the last major political convention for which the question “How can we make this an effective television program in support of the party?” was not the focal point.

After the debacle in 1968, the party significantly altered its delegate selection rules in an effort to make the process more transparent and more responsive to grassroots concerns. The result not only made open primaries the main form of delegate selection, it also empowered new party constituencies focused on new issues and disempowered more traditional constituencies like labor unions and urban political machines.

This led to marathon platform debates on issues like gay rights, reproductive freedom, gender equity, and personal identity, issues which today seem like normal political fodder but at the time had never been addressed so directly by a major political party.

McGovern had difficulty selecting a running mate. At least four major party figures turned him down; by the time he settled on Thomas Eagleton, rank-and-file delegates were so disheartened that they turned what should have been the procedural formality of nominating Eagleton into a marathon spectacle during which seven other candidates were formally nominated and dozens more received at least one vote, including dead people, fictional characters, and the chairman of the Chinese Communist Party.

These shenanigans pushed McGovern’s acceptance speech to nearly 3 a.m. EST, well past television’s prime time. Eagleton was removed from the ticket (replaced by Sargent Shriver) less than three weeks later when it emerged he had received electroshock therapy for depression.