More than any other event of the eighteenth century, the French Revolution, which began in 1789, changed the face of modern politics across Europe and the world.

It overturned the longstanding French system of monarchical government and introduced the ideas of liberty, equality, fraternity, and human and civil rights to modern political practice. It also helped to usher in modern nationalism and nation-states. And it became a model of revolutionary political change that was followed throughout the world from Europe, to Haiti, Latin America, Russia, and East Asia.

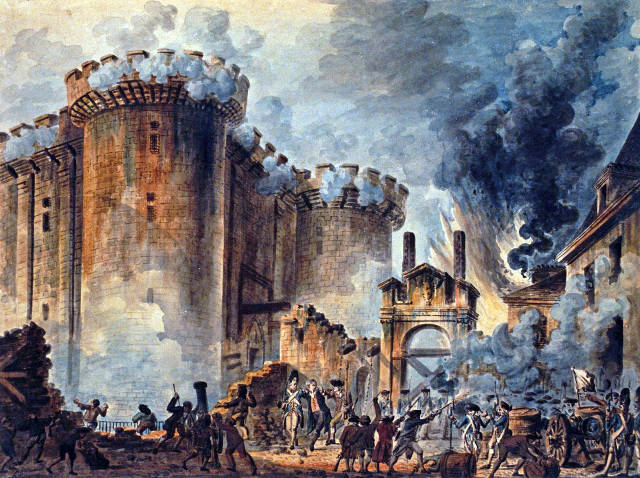

And it all began one July day when the people of Paris captured a fourteenth-century gothic prison known as the Bastille.

In the summer of 1789, Paris was at a boil. The people had been suffering from food shortages and the weight of taxes used to pay King Louis XVI’s vast debts. And they found themselves in the midst of unprecedented political turmoil caused by the opening of the Estates General, France’s Parliament, for the first time in more than one hundred years. Many Parisians were also angered by the dismissal of the popular minister Jacques Necker on 11 July. But what really stirred them was the fact that, since the beginning of June 1789, Louis XVI had concentrated troops around Paris.

The sense of menace that the militarization of the city caused provoked a march to the Hôtel des Invalides, where they looted approximately 3,000 firearms and five canons. The weapons, however, required gunpowder, which was stored in the Bastille.

After arriving at the prison and negotiating with its governor, marchers burst into an outer courtyard and a pitch battle erupted. By the time it was over, the people of Paris had freed the prisoners held in the Bastille and taken the governor captive (the governor and three of his officers would soon be killed and then beheaded by an infuriated crowd, their heads paraded through the streets atop pikes). The cost was steep: nearly one hundred citizens and eight prison guards were killed.

All of this happened on July 14, which has been known in France and all over the world as “Bastille Day” ever since. Hearing that the Bastille had fallen, Louis XVI asked the duke de La Rochefoucauld: “So, is there a rebellion?” To which the duke retorted: “No, Sire, a revolution!”

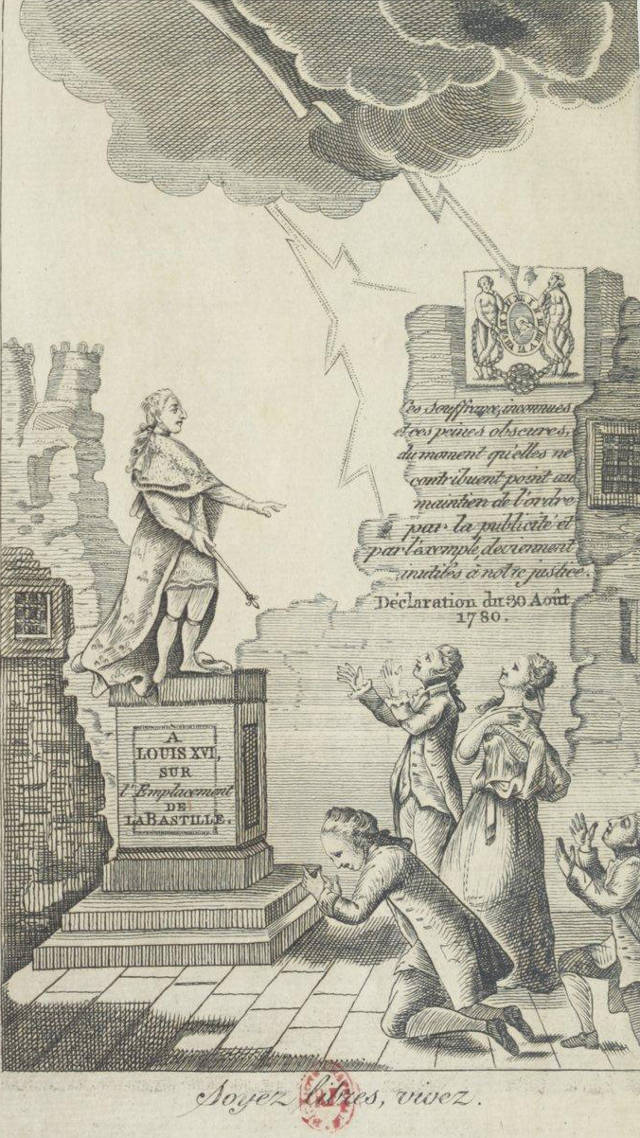

Like many other iconic revolutionary acts, the storming of the Bastille was not intended as such. Yet, it was a pivotal moment in the unfolding of the French Revolution—the spark that forced the King to begin concessions and emboldened the people’s movement to overthrow him (and later to behead both him and his wife in the hope of burying monarchy forever).

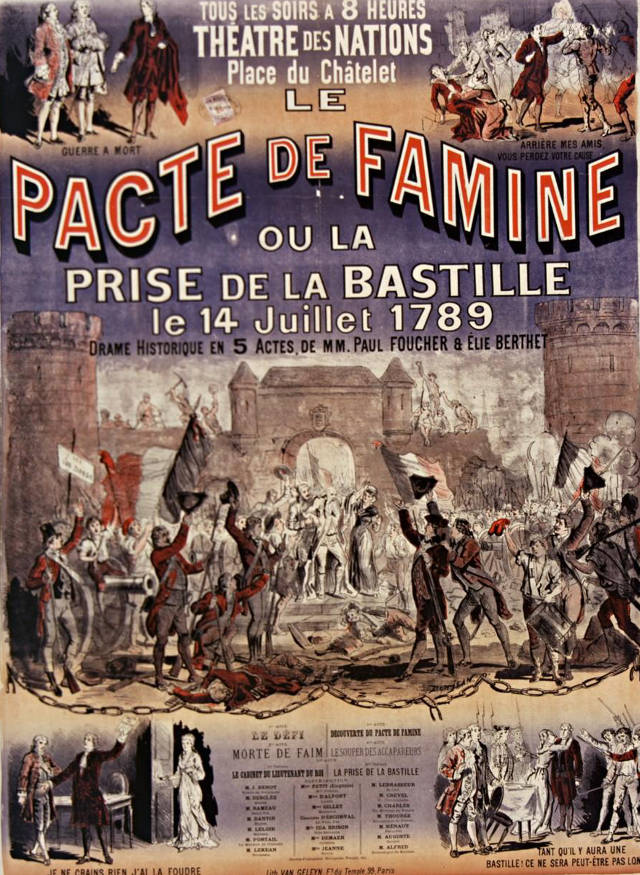

Throughout the nineteenth century, the fall of the Bastille was chronicled by historians, depicted by artists and celebrated by common people.

In 1880, the French chose to make the Storming of the Bastille their national holiday. Through all the upheavals of France’s century of revolutions (1789-1871), the events of July 14 retained their power as the most powerful symbol of the people bringing down a despotic government and putting an end to arbitrary rule.

Today, in times of deterritorialized terror, outsourced prisons, bitcoins, and subcontracted state and military arbitrariness, the Storming of the Bastille might look like a quaint scene from an old-fashioned opera. Yet, the world in recent years has had its own share of Bastilles, from Tahrir Square in Cairo to Independence Square in Kyiv (not to mention the recent commemorations of the 1989 Tiananmen Square Movement).

The taking of the Bastille also reminds us that on the long, bumpy road toward representative democracy—that is, on the road toward the rule with the consent and for the benefit of the people—it is sometimes easier to strike down the visible signs of authoritarian power than to deal with the complicated, often shadowy sources of that power. And, after it took the French the better part of a century to embed the democratic ideals of 1789, the Bastille prompts us to remember just how hard it is for the voices of the people to be transformed into the enduring instructions of democratic governance and the rule of law.

The storming of the Bastille also reminds us that modern citizens were not only born out of acts of valor or cruelty, but also out of the act of remembering and out of the strong desire for justice.

The fall of the Bastille was one of the moments in the eruption of the modern popular historical consciousness and the power of history and historical consciousness to the proper functioning of a democratic society.

In 1789, the Bastille was not just a prison but also served as an archive holding the documents of the Parlement de Paris, of the King’s household, and of the Parisian police. Pillaged, scattered and burned during and after the fall of the fortress, large parts of the archive were recovered by Beaumarchais and by the Russian diplomat and bibliophile Pierre Dubrowsky.

Realizing the importance of the Bastille archives, the Commune de Paris appealed to the citizens to return any documents they might have in their possession in order to help document the future trial of royal despotism. The citizens of Paris answered promptly and 600,000 pieces were returned. Today, together with a copy of the documents saved by Dubrowsky, they constitute the Archives de la Bastille found at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

On July 14, 1789, the people of Paris seized not only a prison, but also control over their own historical memory, too. It is this sudden blooming of subjects into citizens, willing and able not only to change history, but also to contribute to its writing, which set the precedent for all the revolutions of the modern age.

It is a privilege which we should strive not to lose.