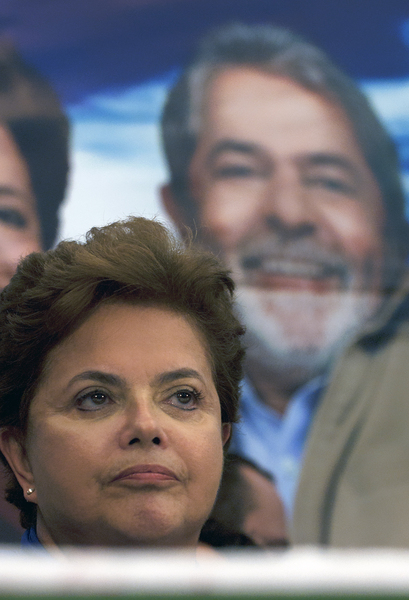

Brazil's President-elect Dilma Rousseff stands before an image of her mentor, President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva (Lula). The immensely popular Lula has held the Presidency since 2002 and his endorsement helped propel her to victory in the October 2010 elections. Breaking with its long and painful history of political and economic troubles, Brazil has moved dramatically over the last two decades toward greater stability and growing global ascendancy. (Agencia Brasil photo)

Eight years ago, the prospect of a victory by the leftist Workers' Party candidate Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in Brazil's 2002 presidential election sent shockwaves through international financial markets, prompting the IMF to step in with an emergency loan to steady the nerves of investors fearing default by a Lula government. This year, things could not be more different. President Lula da Silva is completing his second term with an 80% popularity rating and is barred by the constitution from seeking a third consecutive term. Nevertheless, his presence has been heavily felt in the election as the two leading presidential candidates battled to assure voters that they would carry on Lula's legacy. Meanwhile, Brazil has paid off its foreign currency-denominated debt; has become a net creditor to the IMF; and is enjoying strong growth with heavy inflows of investment. With the recent discovery of vast reserves of deep sea oil, and having won the chance host both the 2016 Summer Olympics and 2014 World Cup in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil seems poised to fulfill its perennial promise of becoming the 'country of the future,' despite many challenges ahead.

On the history of current events in Latin America and Brazil, readers may also be interested in Populism and Anti-Americanism in Modern Latin America and Between Black and White: The Complexity of Brazilian Race Relations.

On October 31st more than 135 million voters went to the polls in Brazil to elect their next president. They chose a career technocrat named Dilma Rousseff of the leftist Worker's Party (PT), who was the hand-picked successor of Brazil's current president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (known as Lula).

The vote was a run-off between Rousseff and José Serra of the centrist Brazilian Social Democratic Party (PSDB), who were the top two vote-getters in Brazil's October 3rd general election. And Rousseff won decisively in the second round, claiming 56 million votes—fully 12 million more than her opponent.

The general election also included contests for all 513 members of Brazil's Chamber of Deputies, two-thirds of the Federal Senate seats, as well as governors and representatives in all 26 state legislatures and the Federal District.

It was thus a big election, and an historic one. Brazilians elected not only their first female president, but they did so at a time of strong growth and prosperity, with little of the economic volatility that has until recently surrounded presidential elections in Brazil. At the same time, the elections indicate that peaceful, civilian democracy—which returned to Brazil only in 1985 after long stretches of political unrest and military rule in the 19th and 20th centuries—is hopefully here to stay.

The direction in which Brazil's new president takes her country is deeply consequential not only for that nation of 190 million, but also for global geopolitics. In a matter of just two decades, Brazil has gone from long being a perennial economic laggard—mired in high inflation and slow growth that won it the moniker of Latin America's "sleeping giant" for its vast unrealized potential—to now being the eighth largest economy in the world, a major exporter of oil to the United States, and an ever more important player in hemispheric and global politics.

Recent years have seen Brazil take on an ever bolder international profile, a trend that is unlikely to change under the next administration. Brazil currently holds a two-year nonpermanent seat on the United Nations Security Council and is lobbying vigorously to assume a permanent seat.

Brazil is also poised to bypass Venezuela as the hemisphere's major oil exporter; and with an economy larger than those of India and Russia, and with nearly two times the per-capita income of China, Brazil is on track to become a major force in the global economy.

How Things Change

One of the most striking features of Brazil's 2010 election is the economic stability and strong growth that surrounded it. The Brazilian economy is expected to grow at a rate of 7% this year, and it was among the first emerging market economies to recover from the global recession.

As recently as the early 1990s, however, Brazil remained engulfed in decades-long economic tumult with prices rising at a rate of 80% per month. At that rate, a sandwich that cost $1 in January would cost $1,000 by year's end. Inflation had long cast a heavy pall over Brazil's economy, dampening private investment and deepening poverty and inequality.

It was only in 1994 that Brazil's so-called "inflationary disease" was finally cured by a team of academic economists who introduced a new currency, the Real, which achieved the long-elusive goal of stability and credibility.

The quelling of inflation did not solve all of Brazil's economic problems, however, for the country remained heavily indebted and dependent on foreign inflows of capital – vulnerabilities that were laid bare in the run-up to the 2002 general election.

That election pitted José Serra of the Brazilian Social Democratic Party (PSDB) against Lula of the PT, in his fourth attempt to win the presidency. Lula's campaign was bolstered by a sense of exhaustion after eight years of difficult structural reform in Brazil's economy.

As Lula took the lead in opinion polls, however, the prospect of his victory sent shockwaves through international markets, elevating Brazil's sovereign risk rating, which pushed up the price at which the government could borrow on international markets. By September 2002, when a Lula victory seemed likely, fears of default left the benchmark Brazilian government bond trading at a face value of just 49 cents to the dollar. The country's hard-won economic stability seemed to be imperiled by the prospect of a Lula victory.

Much of investors' concern came from the candidate's fiery rhetoric during his three earlier presidential campaigns, which had included calls for the renegotiation of Brazil's foreign debt and for meaningful redistribution of Brazil's highly unequal income and land. Investors also feared that the former metalworker and union leader would place little value on fiscal and monetary discipline.

But Lula's 2002 campaign was different; and so was Lula. Having tamped down the heated rhetoric and replaced his more casual attire with sharp business suits, Lula hired a high-power marketing firm to run his campaign advertising. The firm used focus groups to craft an image of Lula as moderate and friendly, including by adopting the motto "Lula peace and love."

Even as Lula made gains to win over the domestic electorate, international capital markets remained skeptical. In the month before the 2002 election as markets continued to gyrate and outflows of capital from Brazil reached $60 billion, the IMF stepped in with $30.4 billion stand-by credit.

In an unprecedented move, the IMF agreement was signed not just by then President Fernando Henrique Cardoso (elected President in 1994 and 1998), but also by Lula and the other two front-running candidates. They all committed to maintaining a primary fiscal surplus (the budget balance before interest payments on outstanding debt) of 3.75% of GDP in the next government.

After his decisive second-round victory, Lula took further measures to bolster market confidence in his government. He appointed Henrique Meirelles, a former executive of BankBoston, to head the central bank, and selected a market-friendly Finance Minister, Antonio Palocci.

Lula also pledged to maintain an even larger primary surplus (4.25% of GDP) than was dictated by the IMF loan. In effect, in order to persuade investors that he was not a risk to the country's stability, Lula became even more economically orthodox than his predecessor—whose market-friendly policies he had long subjected to withering criticism.

Lula's Government: Continuity and Change

Those early choices presaged the more pragmatic, rather than strictly ideological, course of Lula's government. Despite Lula's explicitly anti-Cardoso campaign rhetoric, his governance has been characterized by a striking continuity, rather than departure from Cardoso.

For instance, one of the most difficult political battles of the Cardoso presidency was his effort to reform Brazil's regressive and deficit-ridden social security system. Lula's Workers' Party fought bitterly against Cardoso's social security reform every step of the way, as their core constituents—the public sector workers—are a main beneficiary of the system's largess.

Yet, shortly after taking office, Lula stunned his base by picking up the reform battle where Cardoso left off. In his first year in office, he passed a constitutional amendment to reform the public sector pension system. That effort, which addressed an important source of Brazil's budget deficit, sent a powerful signal of credibility to international markets and won the government strong praise from investors. But it came at a high political cost, prompting a rupture within the Worker's Party and the disillusionment of one of the PT's strongest allies, the civil servants.

Lula's antipoverty policies also bear the heavy imprint of his predecessor. The centerpiece of Lula's social policy agenda is a conditional cash transfer program called Bolsa Familia (Family Grant), which offers monthly stipends to mothers as long as children remain in school and meet certain health care criteria.

Although the program is closely associated with Lula in the public mind, it was launched at the national level by the Cardoso government under the name Bolsa Escola (School Grant). Lula greatly expanded the program coverage to reach 11 million families, and merged it with other social benefit programs under the umbrella of a broader social welfare program called Fome Zero (Zero Hunger).

Lula's economic policy parted company from that of Cardoso, however, on the issue of the state's role in the economy (and it is expected that Rousseff will follow Lula's course here). Lula promoted an expanded state role in several sectors of the economy, such as in credit allocation. He did so by using the state development bank (BNDES) to extend hundreds of billions of dollars worth of loans to private companies to spur domestic, and international, investment.

Lula also promoted a broader role of the state in the petroleum sector, which is dominated by the government-controlled oil company Petroleo Brasileiro SA, known as Petrobras. President Cardoso had partially privatized Petrobras in the 1990s.

However, the discovery of immense new oil reserves—estimated at 80 billion barrels—in Brazil's offshore "pre-salt" oil fields has led to a reversal of this trend. It has also positioned Petrobras to become a global leader in the petroleum industry and within the near future, a regional leader in petroleum exports (Brazil is currently second to Venezuela in its proven reserves of oil and production).

The discovery has prompted the Brazilian government to move to claim a greater role in the development of these oil fields and the vast resources they hold. In September 2010, for instance, the Brazilian government effected a $67 billion offering of Petrobras shares, in which the government expanded its holding from 40 to 48% (and from 57.5 to 64% of voting shares). The government is also preparing legislation to expand Petrobras' role in the future operation and development of the deep-water oil fields, which also represents a shift from Cardoso's effort to broaden the role of the private sector in oil production.

Lula also charted a foreign policy course that has been increasingly independent and assertive on the international stage—a break from Brazil's "unwritten alliance" with the United States that began early in the twentieth century. This shift included strengthening ties with Fidel Castro of Cuba and Mahmoud Ahmadinejad of Iran, and an unsuccessful effort along with Turkey to sidestep the United States-led negotiations with United Nations Security Council and broker a deal over Iran's nuclear program.

Lula asserted Brazil's economic weight in global economic forums such as the Group of 20 and the World Trade Organization, and took the lead in global negotiations over climate change, food security and the international financial architecture.

He sought to strengthen Brazil's regional leadership by forming the Union of South American Nations and re-launching Mercosur, the South American free trade zone. Lula has campaigned to win a permanent seat for Brazil on the United Nations Security Council and Brazil has won the claim to host the 2016 Summer Olympics and the 2014 World Cup. [Read here for more on the Olympics and the World Cup.]

Whether or not President-elect Rousseff follows the bold international diplomacy course set by Lula, the country will find itself directly before the global spotlight during the next presidency.

Lula's Shadow in 2010

The social, economic and political circumstances surrounding Brazil's election of 2010 could scarcely be more different than they were just eight years ago when President Lula da Silva was first elected.

Not only has Brazil paid off its foreign currency-denominated debt, but it has also shifted from being a debtor to a creditor to the IMF, having recently provided it a $10 billion loan.

Brazil's economic growth has averaged a steady 4% in recent years despite the global economic crisis, which is fully double the country's average growth rate of the previous decade. And unemployment is at the lowest level recorded by the nation's statistical agency, IBGE.

A considerable part of Brazil's economic boom owes to favorable international economic conditions, including strong demand—particularly from Asia—for commodities such as iron ore, petroleum and soy beans that Brazil exports.

At the same time, high international liquidity has spurred heavy flows of investment to developing nations. Indeed, developing nations as a whole are enjoying the best terms on which to borrow on international capital markets in decades.

These trends have not only fueled domestic growth, but they have also offered Brazil's government the fiscal leeway to finance the expansion of antipoverty social programs and the sharp increases in the minimum wage, which has seen its value in recent years increase 50% above inflation.

Together, these factors have brought a decline in poverty in Brazil from 34% of the population in 2002, to 22.6% in 2010. And inequality has fallen sharply with 29 million Brazilians joining the middle class between 2003 and 2009. It has been remarkably swift social transformation.

Also in sharp contrast to 2002, international markets have largely greeted this election with a shrug. Even though the two leading candidates differed on policies such as the pace of debt reduction and interest rates, both were viewed by market actors as relatively "safe" and both have pledged to continue the general course of the Lula government. This perception is striking in part because of the strong negative reaction of global investors to the leftist Workers' Party earlier this decade.

Evidence of investors' confidence in the leftist party and candidate can be found in the heavy inflows of capital to Brazil in September and October 2010, which were so strong that the government took measures to prevent excessive exchange rate appreciation. For a country such as Brazil that relies on exports, currency appreciation raises the cost of the nation's goods on international markets, dampening their competitiveness. Such measures included intervention in capital markets to restrict the effects of capital inflows on the domestic economy, and a doubling of a tax on foreign purchases of bonds in Brazil, which aimed to reduce upward pressure on the country's currency.

This election was also the first presidential contest since Brazil's return to democracy in 1985 in which the name Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva was not on the ballot. Nevertheless, Lula's presence was powerfully felt in this election.

Indeed, the victory by Dilma Rousseff, his hand-picked successor, offers a powerful signal of the country's satisfaction with the status quo and with the economic course charted by the Lula government. Not only has Rousseff never held elected office, instead having long toiled behind the scenes as a technocrat, but as recently as January she was also battling lymphatic cancer.

For some analysts, the expansion of prosperity and of economic security is a principal reason why the outgoing president could hand-pick a relatively unknown technocrat to be his successor. Despite corruption scandals in his party and cabinet, Lula enjoys a colossal 80% approval rating, prompting President Obama recently to call him "the most popular politician on earth."

Throughout much of the campaign, the two top candidates—Serra and Rousseff—jockeyed fiercely to establish themselves as the one more likely to carry on the work of the Lula government.

Serra claimed an early lead in the election in large part due to the lack of name recognition by Rousseff. Polls moved sharply in her favor, however, after Rousseff officially declared her candidacy and began to campaign in earnest with Lula closely at her side. As Lula sought to transfer his enormous popularity to Rousseff, he was more than once found in breach of electoral laws for using his official position to campaign, for which he faced nominal fines.

In the final months of the election, Rousseff seemed to be on course to win a majority of votes in the first round of the election, with a clear double-digit lead over her closest rival. A late surge of support for the Green Party candidate (Marina Silva) denied Rousseff outright victory in the first round. Nonetheless, Rousseff held her lead in the October 31 run-off and won a decisive 56.05%, compared to 43.95% for José Serra.

The Changing Face of Brazilian Politics

For a country with an average income just a quarter that of the United States, and with only a recent history of democratic competition, the sophistication and seamlessness of Brazil's electoral process is nothing short of remarkable.

This is particularly so given that the 2010 election was just the sixth presidential contest since Brazil's 1985 transition to civilian democracy after 21 years of dictatorship. Prior to the 1964 coup d'état that ushered in two decades of military rule, moreover, Brazil had experienced just two decades of democratic politics in the nation's 500 year history—and at that, with only a limited franchise. Indeed, it was only in 1988 that voting became truly universal with the inclusion of illiterate voters in the electorate.

Today, the voting system in Brazil is nearly all electronic (exceptions are made only for the remotest areas). No names appear on the ballot, and electors type in numbers representing the specific code for each candidate. Turnout at elections is high, but voting is mandatory and the failure to vote without justification is punishable by a fine. Voter apathy or displeasure thus is channeled in ways that included the submission of blank or null ballots, or through protest votes.

In addition to the new sophistication of Brazil's elections, the very fact of Lula's presidency, leaving aside his immense popularity, marks an historic shift in Brazilian politics, which had been long dominated by elites.

Lula was born in dire poverty in the rural interior of Brazil's northeastern state of Pernambuco, one of 8 surviving children of a poor rural family. His family migrated to the industrial Southeast state of São Paulo when he was a child. Having only completed schooling to the fourth grade, Lula found work on the streets as a shoe-shine boy and eventually landed an industrial job as a lathe operator where he lost his finger in a workplace accident.

He rose in the metalworkers' union hierarchy, taking a leadership position in the labor movement as it confronted Brazil's military dictatorship in the 1970s, holding strikes and public marches demanding a return to democracy. In 1980 Lula became a founding member of the Workers' Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores, or PT), which gradually rose from a minor presence in Brazil's National Congress to be one of the largest in the legislature.

Such a rise from dire poverty to the highest office in the nation has allowed Lula to connect to the masses of poor Brazilians who have become his electoral base.

By contrast, Dilma Rousseff lacks both the compelling life story and her own broad connections to an electoral base. Born in a middle-class family of a Bulgarian immigrant, Rousseff came of age under the military dictatorship in Brazil and joined other college students in left-wing armed resistance. She was arrested and is said to have endured torture at the hands of the military during her two years of detention.

After her release, Rousseff returned to college and studied economics, and began a career in government service. Rousseff was not a member of the Worker's Party throughout her early career; indeed, she only joined the PT in 2000. Instead, she was linked to the Party of Brazilian Workers (PTB) in which she rose through the bureaucratic ranks as a skillful technocrat.

After joining the PT, Rousseff moved on to national level politics and was appointed Lula's energy minister in 2003. After a corruption scandal in 2005 forced the resignation of José Dirceu, Lula's Chief of Staff (Chefe da Casa Civil), Rousseff was appointed to that position and became the president's chief minister and close advisor.

A New Brazil

Despite the tremendous strides the country has made in recent decades, many challenges remain for the new president. Among them are still-high levels of poverty and inequality, an uneven educational system, and alarming rates of violence.

Not only do vast segments of the Brazilian population remain in conditions of deep poverty, but many have difficulty accessing the social benefits enjoyed by the more affluent, including high quality education and social services.

In the realm of education, Brazil spends approximately the same share of GDP on education as the most affluent countries, but it inverts the typical spending priority, lavishing the lion's share of spending on higher education, which is accessible to just a few, who are generally the more affluent segment of the population.

The next president will also have to confront the problem of violence and weak rule of law. With plans underway for the Olympic games in Rio de Janeiro, the city's high rates of violence—much of it at the hands of drug gangs and informal militias—have drawn international concern.

Homicide rates in Brazil are among the highest in the world, averaging 25.2 for every 100,000 people (compared to 5 for every 100,000 people in the United States). Such violence had doubled between 1980 and 2002, making homicide the leading cause of death for Brazilians age 15-44 earlier this decade.

Yet, like many things in Brazil, violence is quite unevenly distributed, and is improving for some. Whereas the largest metropolitan areas have made great strides in combating violence—the city of São Paulo has experienced a 70% drop in the homicide rate between 1999 and 2008, reaching a rate of 11.23 homicides per 100,000 people in 2009—violence has grown dramatically in smaller cities of the interior, which have seen a 37% rise in the homicide rate in the past decade.

Women and children are also frequently victimized by social violence. A study issued this year found that more than 41,000 women in Brazil were killed in acts of domestic violence between 1997 and 2007—a rate of ten per day. With more than 150 people killed each day in 2005, Brazil's murder rate has compared to some low-intensity war zones.

For many people, moreover, the police offer little security or protection from such violence, and are even perpetrators of it, often with impunity. For many of the poorest citizens, justice thus seems to be reserved for the most affluent.

As she takes over the Presidency, Rousseff thus faces a difficult challenge in quelling such high rates of violence and strengthening the rule of law. These will be crucial for the continuation of Brazil's remarkable achievements in political and economic development.

Fernando Henrique Cardoso. The Accidental President of Brazil: A Memoir. Public Affairs (2007)

Thomas Skidmore. Brazil: Five Centuries of Change, 2nd edition. Oxford University Press (2009)

Robert M. Levine and John Crocitti (Editors). The Brazil Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Duke University Press Books (1999)

Larry Rohter. Brazil on the Rise: The Story of a Country Transformed. Palgrave Macmillan (2010)

Peter Kingstone and Timothy J. Power (Editor).Democratic Brazil Revisited. University of Pittsburgh Press (2008)

Werner Baer. Brazilian Economy: Growth and Development, 6th Edition. Lynne Rienner Publishers (2007)

Richard Bourne.Lula of Brazil: The Story So Far. University of California Press (2009)

Riordan Roett. The New Brazil. Brookings Institution Press (2010)

Websites

Governments on the WWW: Brazil

Latin American Network Information Center: Brazil

Jornal do Brasil (newspaper, in Portuguese)