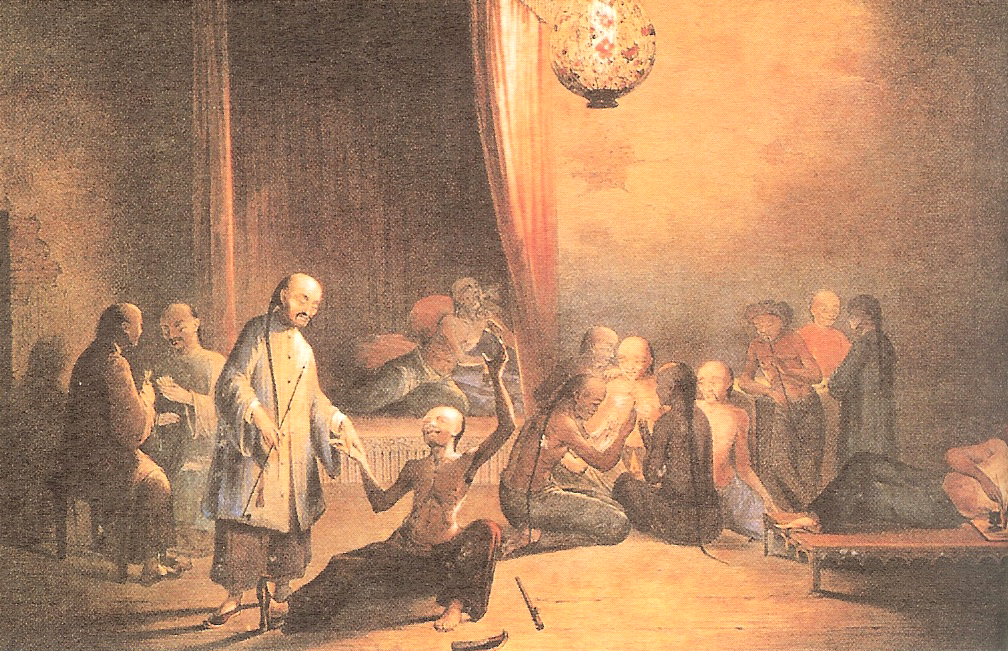

The Opium Wars (1839-42; 1856-60) are generally seen as symbolic of Chinese defeat in the face of British imperial power and commercial interests.

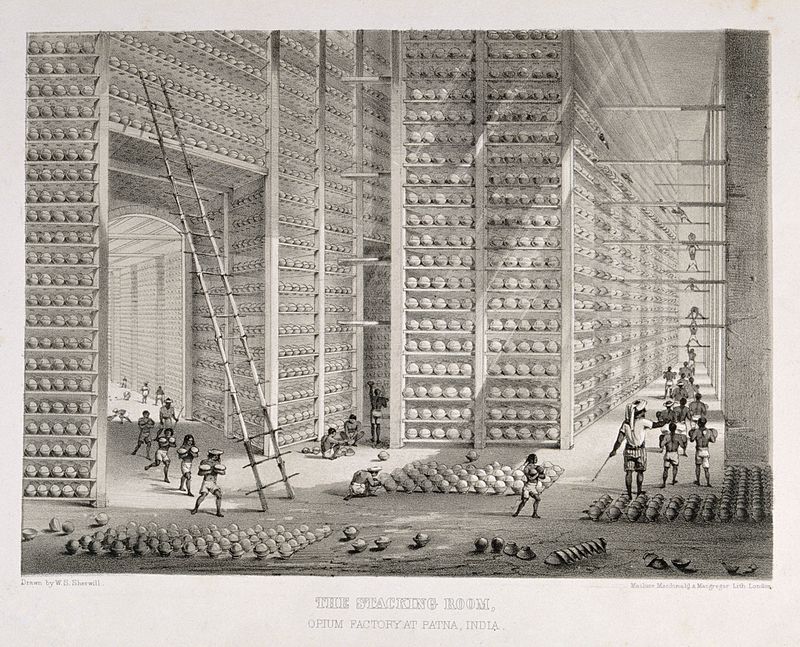

China wanted to stem the flow of opium into China from British India. The Chinese wanted to protect their people from opium addiction. The British defended the principle of “free trade” in pursuit of vast profits. China lost the battle and opium continued to flow.

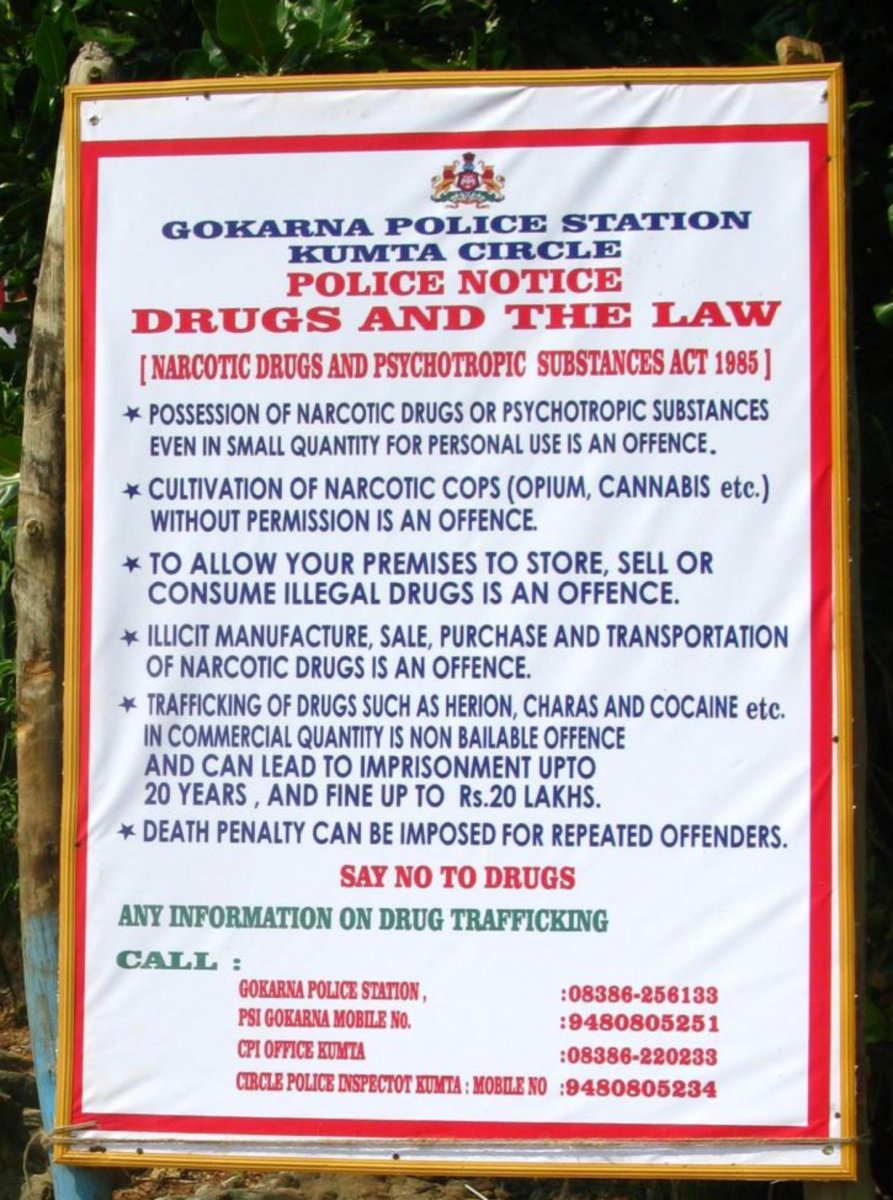

But by the First World War (1914-18), the idea that a nation was justified to go to war to protect trade in drugs had been discredited. When the League of Nations came into being in 1920, nations and empires began to prioritize anti-drug trafficking laws as an important component of their activities.

In his aptly named Opium’s Long Shadow: From Asian Revolt to Global Drug Control, Steffen Rimner examines how this revision of international thinking came to be.

The shift, as Rimner charts it, came not from governments themselves but from what we might call civil society groups and non-governmental organizations. They created an international movement against the opium trade. By broadening the scope of his analysis beyond empires and nations, Rimner demonstrates that there were many more forces at play in the anti-opium movement.

Rimner argues that while an early protest was made by Prince Gong, the Qing Chief Secretary, in 1869, his words far outlived his initial campaign. His rhetoric influenced anti-opium advocates in Great Britain, the United States, Japan, India and Australia. It transcended the realm of international diplomacy and made its way into non-governmental channels. Thus was Britain’s Society for the Suppression of the Opium Trade (SSOT) founded in 1874. Though it was based in England, the group operated beyond imperial boundaries.

Rimner considers actors as diverse as the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and the Sharada Saran (a school for girls in Bombay started by Indian social reformer Pandita Ramabai), as well as popular travelers and thinkers such as Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore. These highly mobile people and organizations became the backbone of the anti-opium movement as they translated and circulated Prince Gong’s words of resistance globally, adapting it along the way to serve their various purposes.

It was only in response to transnational pressure from bodies such as SSOT that the British government set up a Royal Commission in 1895 to launch an inquiry into the evils of the opium trade. After an extensive and bureaucratic inquiry the Commission (happily for British traders) reported that a ban on the trade of opium would be contrary to the spirit of free trade, and that opium was no more harmful than alcohol.

Various non-state groups were outraged by the report. They rallied together to provide examples of regions and states where bans on opium had proven effective without a loss of revenue (such as Burma and Japan). These groups also changed public opinion and Rimner demonstrates how that, in turn, played a powerful role in pushing governments to take legal action against the drug trade.

By highlighting this globalism in the anti-opium movement, Rimner argues that transnationalism was not a byproduct of the movement, but essential to its effectiveness.

A vital aspect of using a transnational framework to study world history is the acknowledgement that information, ideas, and people move in all directions, not simply from the “West” to the “East.” Rimner skillfully weaves together national politics with international events in order to build a narrative that pushes against a Eurocentric understanding of the anti-opium movement in particular, and drug control broadly.

Noting that SSOT was inspired by Prince Gong’s declaration, Rimner reveals that the organization did not understand itself as engaging in a "civilizing mission" to eradicate opium from China.

Instead, they sought advice from Qing officials on what would be the most useful way to approach opium control. In addition, by centering discussions around the opium trade between India, China, Burma, Japan, and Singapore, Rimner makes a strong case for a heretofore unacknowledged “Asian” resistance to opium and, by extension, to exploitative British policy.

The strength of this book lies in the way Rimner puts these transnational non-governmental forces at the center of his story. Rimner’s transnational lens encourages us to think beyond opium as an exclusively Sino-British problem. Instead, he turns our attention to what was a truly global phenomenon.

By using a transnational lens, Rimner is able to explain how states and empires came to adopt drug control laws after the First World War—the very same laws that they had resisted in the 19th century.

Opium’s Long Shadow also encourages us to rethink traditional understandings of international relations as unfolding between nation-states. Instead, as the anti-opium movement clearly demonstrates, individuals and non-official groups can (and have) been the vanguards of legal change even in the face of governmental and imperial opposition.