Anyone unfortunate enough to have watched more than a modest portion of cable news in the past two years might be forgiven for believing that we live in the land of "Sarah." Talking heads dutifully dissect the details of her troupe's lives, whether Iditarod Todd's hounding of an Alaskan political ally for failure to reciprocate on camera the benevolence that Sarah bestowed upon him on Facebook; Bristol's future or lack thereof on "Dancing with the Stars"; or former-son-in-law-to-be Levi's path to greatness through the Wasilla mayor's office and the pages of Playgirl.

The incumbent mayor of Wasilla, asked about the potential of facing a challenge from Levi, noted that it would be "wise for him to get a high school diploma and keep his clothes on. The voters like that!"1 And maybe they do. But voters are viewers, and—if cable news content is any indicator—viewers seem to have found a place in their thoughts for Levi.

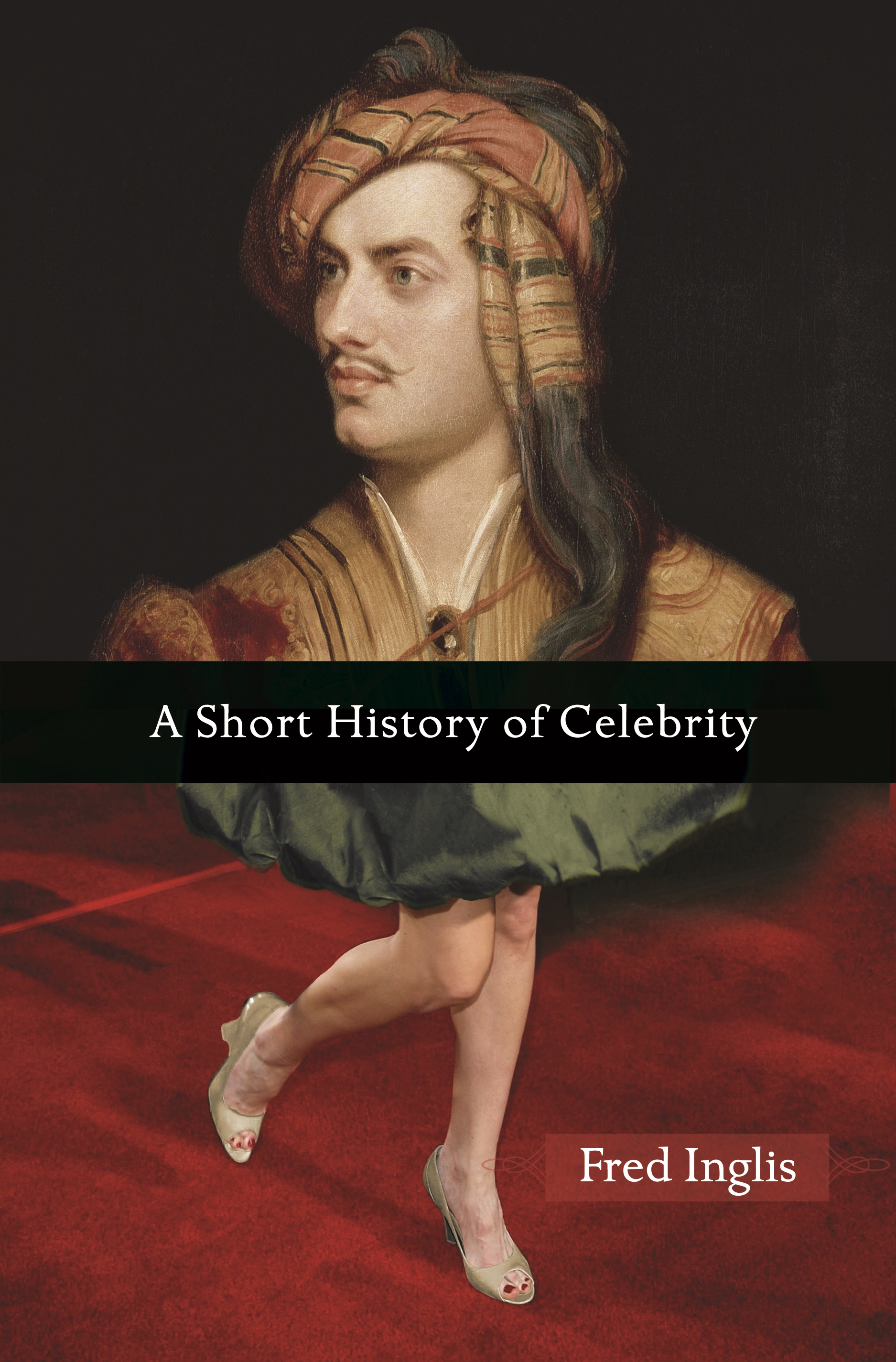

Anyone mystified and incensed by all of the above and its ilk cannot but hope to find some perspective in a book that carries the title A Short History of Celebrity. Fred Inglis, Emeritus Professor of Cultural Studies at the University of Sheffield, is the author of more than twenty books on a broad range of topics—sport, the holiday, media theory, and Clifford Geertz among them—and he draws on decades of reading (and watching, following, and listening) to provide a reflective and rambling excursion into the sources and meanings of modern celebrity.

His basic points are two.

The first—also his "most pointed moral"—is simply that celebrity has a history. Inglis is thoroughly appalled by many of modern celebrity's incarnations, and particularly that "desperate boringness of the people hanging out in the unreality of reality television." Yet, he insists, modern celebrity was not "thought up by the hellhounds of publicity a decade ago," but has rather been in the making for more than two centuries. This circumstance, as he sees it, should offer some solace and perspective to today's hand-wringers (3, 18).

Celebrity, Inglis claims, was a child of the eighteenth century. Unlike "fame"—the reward for achievement or tribute paid to wealth, power, and privilege—celebrity was conferred by "the mere fact of a person's being popularly acknowledged, familiarly recognized, attended to, selected as a topic for gossip, speculation, emulation envy, groundless affection" and so on (57). Three cities were central to its development. In eighteenth-century London, city displaced court as the preferred site of the social scene, while new money engendered a social mobility that challenged old aristocratic ties. The "consumer society" that emerged invented new forms of urban leisure in its theatres, pleasure gardens, coffee houses, novels, and journalism, and Londoners increasingly busied themselves with the pursuit of their actors' and writers' intimate stories. Mid-Nineteenth-century Paris and its grand department stores placed appearance and dress—fashion—at celebrity's core. Gilded-age New York City, in turn, helped to glamourize money and institutionalize the gossip column.

It was not until the twentieth century, however, that celebrity became a defining feature in the lives of the masses. During and after the world wars, Hollywood and new forms of mass media—film, radio, television—helped, in Inglis' words, "to restore immediacy and intimacy to human narrative at just the moment when mass modernity made everything in city life seem so anonymous and fragmentary." It was in this mix that the star, "sacred infant of the century," was born. Politicians the world over sought to make themselves stars and tap into what is, for Inglis, celebrity's potent paradox: the coupling of intense familiarity with distance. This is the "compound" that makes the celebrity sacred in modern society: mass media brings the star into the home, yet simultaneously invests her/him with the "remoteness of the supernatural" (10-11, 156).

Inglis' narrative of the history of celebrity is engaging, but it does not always hold together well. This is particularly true of his coverage of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, which lacks the focus on medium that ties the later chapters together. The book as a whole often reads like a collection of disparate stories—Lord Byron this, Baudelaire that, Adolph Hitler this, Marilyn Monroe that—rather than a coherent narrative or analysis. This difficulty is compounded by Inglis' garrulous writing style. He holds little back, and his editors seem not to have not to have intervened, even though, as he admits at the start, he "wrote the thing headlong" (ix).

Inglis' second point—that celebrities provide "stars to steer by"—is better served by his tendency toward free-ranging commentary. The best celebrities, he insists, are "one of the adhesives which, at a time when the realms of public politics, civil society, and private domestic life are increasingly fractured and enclosed into separate enclaves, serves to pull those separate entities together and to do its bit toward maintaining social cohesion and common values." Inglis is emphatic about this positive role of celebrity in modern life. The stories of celebrities "must and should grip us; fastidious distaste will not do," for "these people have things to tell us about the meaning of our lives." A great celebrity, he maintains, helps people see beyond the harsh realities of everyday life, offers meaning through her/his stories, and provides respite to grateful fans (3-4, 104).

Inglis' emphasis on celebrity's positive role in society is compelling on one level, but it is countermanded on another by his repeated (and more profound) commentary that suggests that, in the final analysis, things today are just as awful and unprecedented as the hand-wringers fear. He laments, for example, that celebrity is increasingly a vocation "to which few are called but far too many are chosen" (216). The popularity of reality TV—Inglis' own greatest bogeyman—makes this a particularly nasty problem. He also writes about the decline of mass politics, and notes that, in modern society, experience is everywhere replaced by spectacle. In the "spectacular society," he writes, it is the star who "has been appointed to perform significant actions for us" (231).

Here it is worth quoting Inglis at some length on the topic of television, both to offer a sample of his distinctive style and to show the pivotal role television plays in his understanding of his topic:

Often it remains unswitched off, unignorable, omnipresent, repeated in several rooms of the house and then, when people are gathered round in attention to its garish fairground effects and costume, its revelation of intimacy, of the bodies and spirits of those it pictures, it serves to mimic significance and action merely be being there. The audience then comes to suppose that the dream of successful action is best, even only, realized on television. To be on TV is the pure form of the successful, fully realized individual (32).

And later:

As the richest economies stretched to breaking point the old ties of neighborhood and community, as the comradely, dangerous connections of the old heavy industries (steel, coal, railroad, shipbuilding, docks) dislimned and reappeared in the Far East, television stories of news and soap were raided by the people in order to fill the empty spaces in their crowded, lonely streets (248-49).

Passages like these leave the reader comparatively unmoved by Inglis' valid enough point that celebrity's "sewerish manifestations" were "there in the nineteenth century, and they are here now" (33). It is his discussion of what is most novel in the history of celebrity—its growing interpenetration of all levels of society in particular—that remains most absorbing. His broadest theme—that "the fresco of celebrities tells us many different stories about ourselves, some unsettling, some bracing, some beautiful, some ugly" (271)—is on the mark, and his book is worth reading for its many arresting thoughts, often beautifully expressed, about the nature of modern society. But if you are thinking about picking up A Short History of Celebrity in hopes of finding some perspective on the gamut of problems that the saga of "Sarah" suggests about the relationship between stardom and democracy, you will not put it down feeling consoled.

1 http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2010/08/10/levi-johnston-mayor-campa_n_677569.html