You may not like getting your flu shot, but you should. On January 28, 2017 the U.S. Centers for Disease Control declared that seasonal influenza had reached an epidemic level and the number of cases of flu has continued to rise since. So far, during of the 2016-2017 influenza “season,” the CDC has collected reports of 444,748 total cases of influenza across the United States and Puerto Rico with a mortality rate exceeding 7.5%. The number of influenza cases in 2016-2017 has been unusually high but it is an important reminder of the long and harmful history of human interaction with the influenza virus. As the flu epidemic grows, Origins offers Top Ten historical “flu facts.”

1. The Etymology of “Influenza”

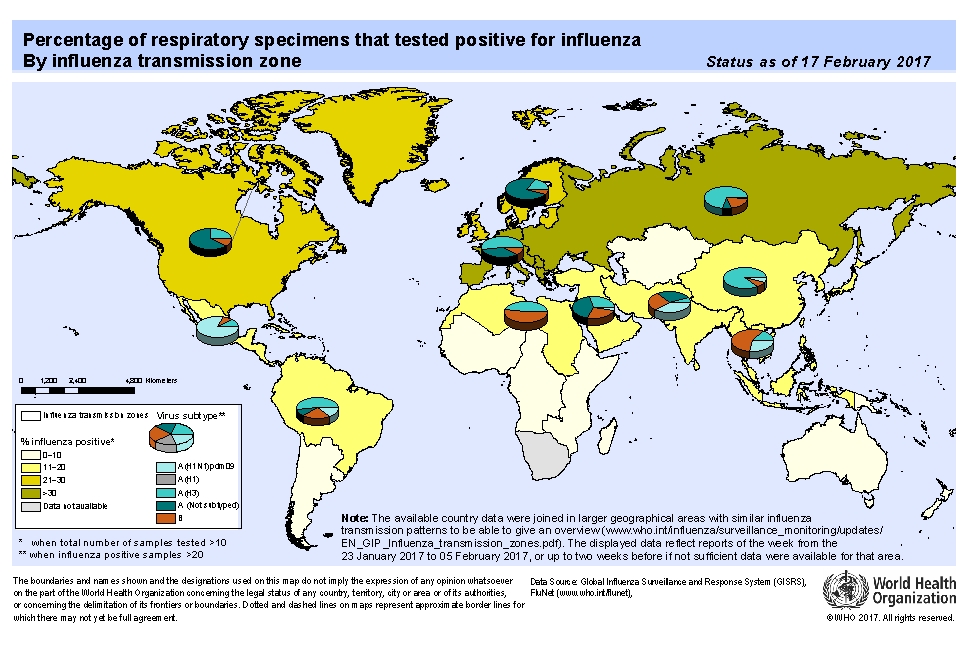

Map of the current influenza epidemic, reported by the World Health Organization.

The word influenza is derived from the medieval Italian word for “influence” (influentia) and referred to the perceived causes of the disease. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the causes or “influences” of the disease were first believed to be astrological, but over time, the explanation changed to “influence of the cold” (influenza del freddo). In 1703, in his graduation thesis, De Catarrho epidemio, vel Influenza, prout in India occidentali sese ostendit,J. Hugger of the University of Edinburgh first used the term in English, but “influenza” was not a commonly used term in England until the 1782 pandemic.

2. The First Pandemic (1580)

Influenza (H1N1) under the microscope.

Scholars have found records of what appears to be epidemic influenza dating at least as far back as 1173 C.E., but the first confirmed influenza pandemic occurred in 1580. The pandemic began in Asia during the summer months, spread quickly to Africa and then into Europe along trade routes from Asia Minor and Northern Africa. Then, over the course of the next six months, the pandemic spread across Europe and the Atlantic to America. Mortality rates were staggeringly high for the time. Scholars estimate 9,000 deaths occurred in Rome alone. Other reports indicate the near eradication of the entire population of several Spanish cities.

3. Influenza in the 18th Century and 19th Centuries

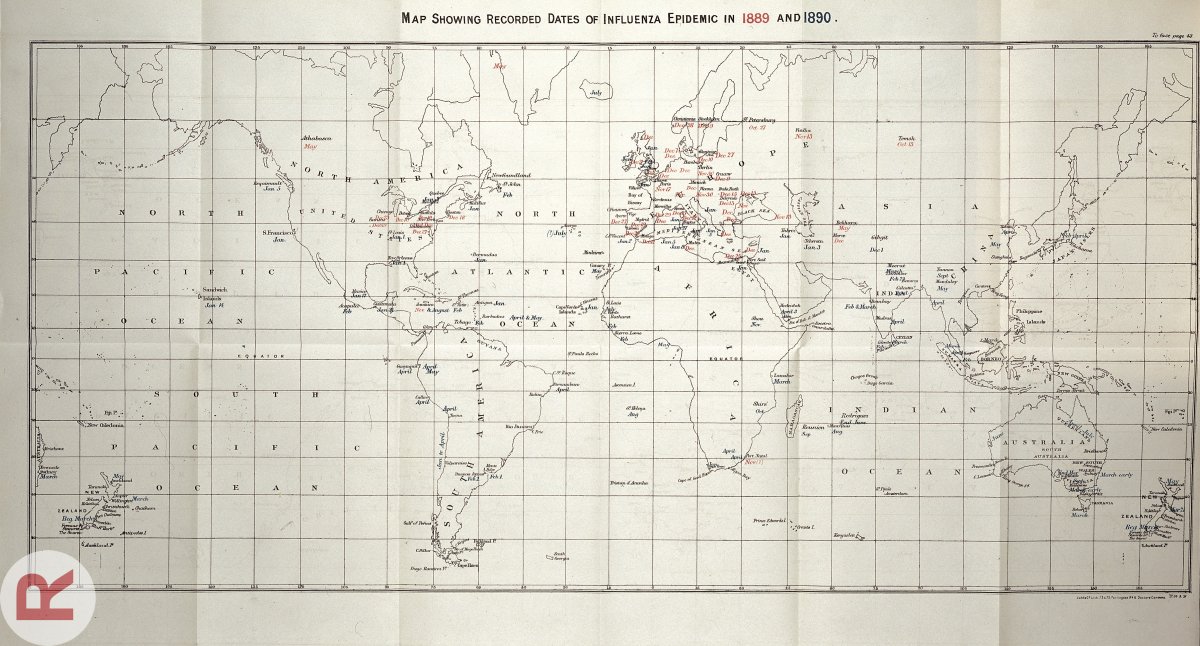

Map of influenza cases worldwide, 1889-1890.

More recent medical records (since 1700) provide much concrete evidence of a series of epidemics and pandemics of what we are almost certain to have been influenza. In spring 1729 an outbreak of influenza began in Russia and over the course of six months spread westward across Europe and eventually all over the known world during the course of a three-year pandemic. In 1781, another major pandemic broke out in China in the autumn, before spreading to Russia and then on across Europe over the course of an eight-month pandemic. Reports indicate that, at the peak of the pandemic, 30,000 fell ill each day in St. Petersburg and that two-thirds of the population of Rome and three-quarters of that Munich succumbed to the disease. Influenza continued its pandemic rampage throughout the course of the nineteenth century, in 1800-1802, 1830-33, 1847-1848, 1857-1858 and 1880-1890.

4. False Findings: An Etiological Error

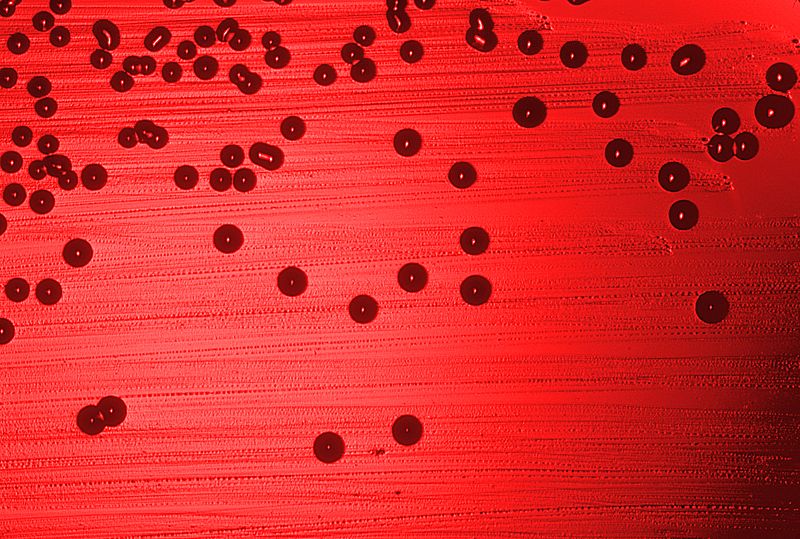

A culture of Haemophilus influenza.

During the 1880-1890 influenza pandemic, while upwards of half of all German town-dwellers contracted at least a mild case of influenza, a German physician named Richard Pfeiffer began to take samples of nasal discharge from his patients. From these samples he cultured a bacterium, which he named Bacillus influenza (or as it more commonly came to be called, Pfeiffer’s bacillus), in 1892. Pfeiffer believed that this bacterium, which we know now as Haemophilus influenza, was the cause of pandemic influenza.

In fact, Haemophilus influenza was not responsible for influenza, which is a viral disease. But the bacteria was responsible for causing opportunistic local infections only possible in an already compromised immune system, such as an influenza patient. Because of the recent discovery of the anthrax, cholera, and tuberculosis bacteria, and lacking a microscope powerful enough to observe much smaller viruses, few of his contemporaries contested Pfeiffer’s findings and his bacterial etiology was accepted as the cause of pandemic influenza for decades to come.

5. The 1918-1919 Pandemic: A History by the Numbers

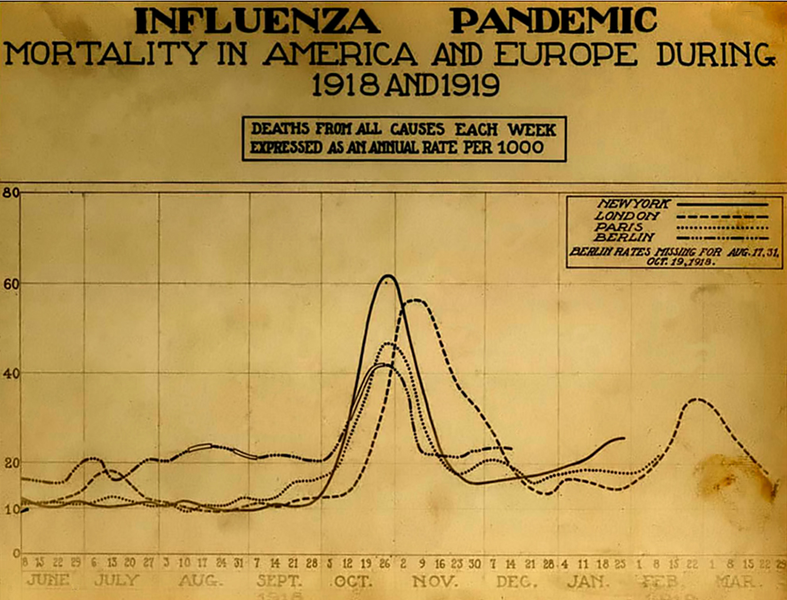

1918-1919 influenza mortality in the U.S. and Europe.

The twentieth century endured the two most important case studies in the history of infectious disease: the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic and the late twentieth century HIV/AIDS global crisis. Influenza made its historical mark during the relentless 1918-1919 pandemic. It struck on the heels of the First World War, which, conservatively, cost the lives of 10 million soldiers from 1914-1918. A recent estimate suggests that influenza cost the lives of more than 30 million people around the world—and in a much shorter time span than the war itself! During the pandemic, more people died of influenza in a single year than during the entire peak of the Black Death (1347-1351), which eradicated between 30-60% of the entire population of Europe. In Britain alone, more than 225,000 people lost their lives to influenza in 1918-1919.

6. Why “Spanish Flu”?

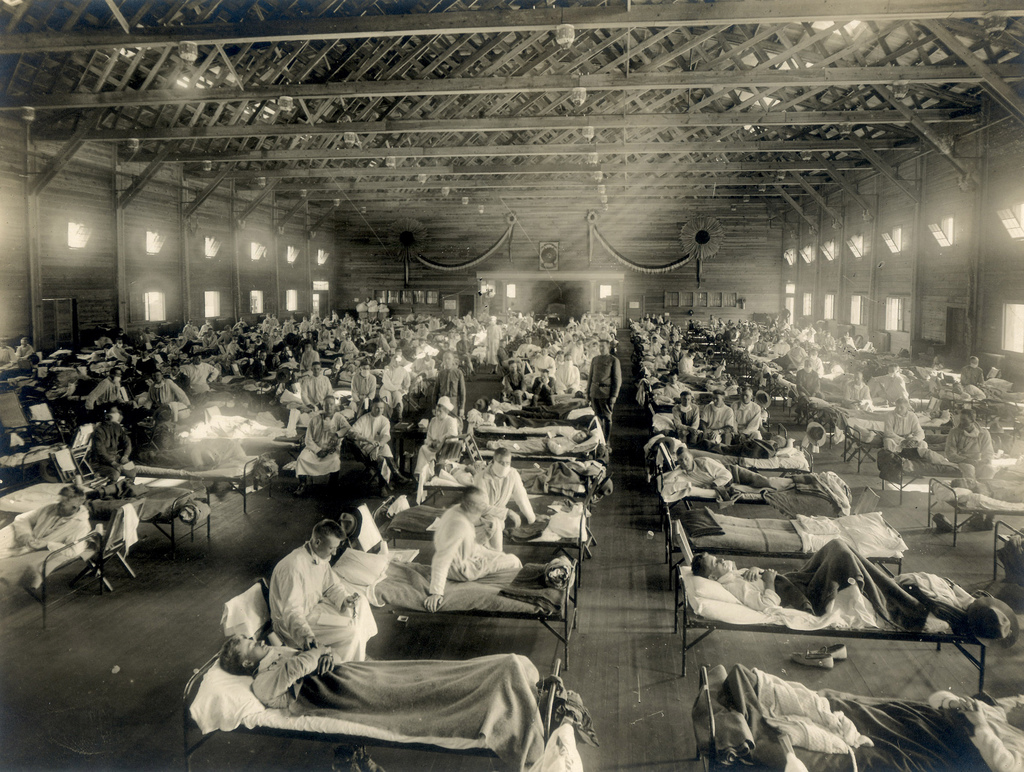

A makeshift influenza hospital at Camp Funston, 1918.

We often hear the 1918-1919 flu pandemic labelled “The Spanish Flu.” However, the first cases of influenza occurred far away from neutral Spain at the military base, Fort Riley, in Kansas. On March 4, 1918 company cook Albert Gitchell reported sick with a fever of 40º C at Camp Funston at Fort Riley. Within days, 522 men reported sick and by the end of the month, 1,100 soldiers were admitted to hospital with influenza. Among them, 237 developed pneumonia and 38 died (approximately 20 percent of those hospitalized). So if the pandemic started in Kansas, why was it called the “Spanish Flu”? Historians still debate this misnomer, but the most likely explanation is due to the early affliction and large mortalities in Spain where it allegedly killed 8 million people in May 1918.

7. 1918-1919 as a Public Health Crisis

The 1918-1919 pandemic quickly circled the globe, and most of humanity felt the effects of the flu as it followed trade routes and shipping lines. The Great War, in its twilight years and during demobilization, exacerbated the rapid diffusion of the pandemic. Outbreaks swept through North America, Europe, Asia, Africa, Brazil and the South Pacific. A shortage of physicians, especially in the civilian sector, was a common phenomenon as many had been lost for service with the military.

In late August 1918, the pandemic virus mutated, and a new more virulent form of influenza broke out almost simultaneously in Brest, France (August 22); Freetown, Sierra Leone (August 24); and Boston, Massachusetts (August 27). The death tolls peaked late fall 1918. Those who were lucky enough to avoid infection had to deal with the public health ordinances to restrain the spread of the disease: public departments distributed gauze masks to be worn in public; stores could not hold sales; funerals were limited to 15 minutes. Some towns required a signed certificate to enter and railroads would not accept passengers without them. Those who ignored the flu ordinances had to pay steep fines.

8. Finding the Viral Cause

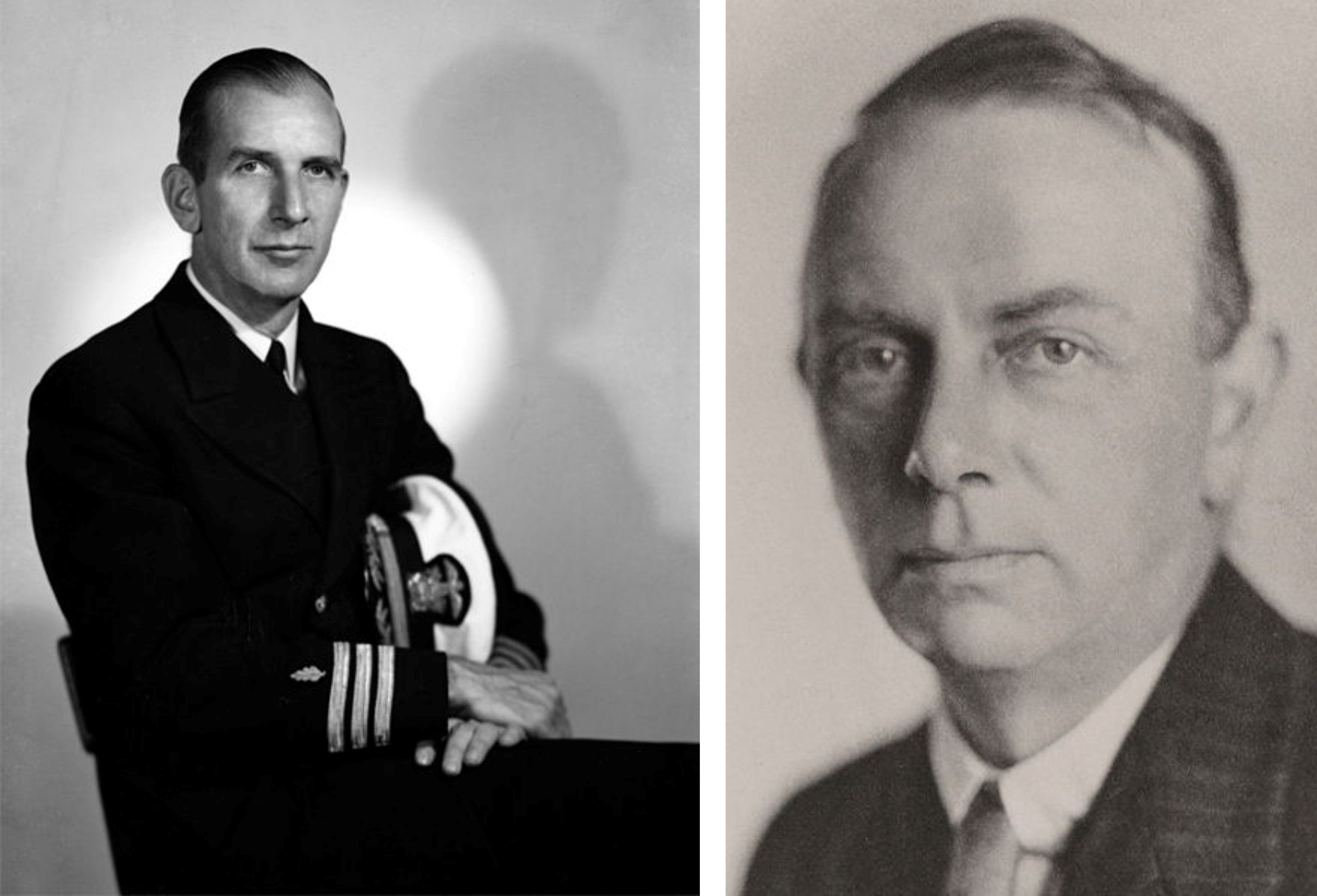

Dr. Edwin Shope (left) and Dr. Patrick Laidlaw (right).

During the 1918-1919 pandemic, scientists assumed that the cause was a new strain of Pfeiffer’s bacillus, but test results found samples of the bacillus in only a small percentage of patient-cases. In the aftermath of the pandemic, scientists re-opened the investigation into the etiology of influenza. In 1931 Richard Shope, an American virologist, made a landmark discovery: a strain of the influenza A virus in pigs. Two years later, Patrick Laidlaw at the Medical Research Council of the U.K. cultured the same virus in humans. Together, in in 1935-1936, the Shope and Laidlaw laboratories correctly identified the H1N1 strain of the influenza A virus, which was the actual cause of the 1918-1919 pandemic.

9. The Quest for a Vaccine

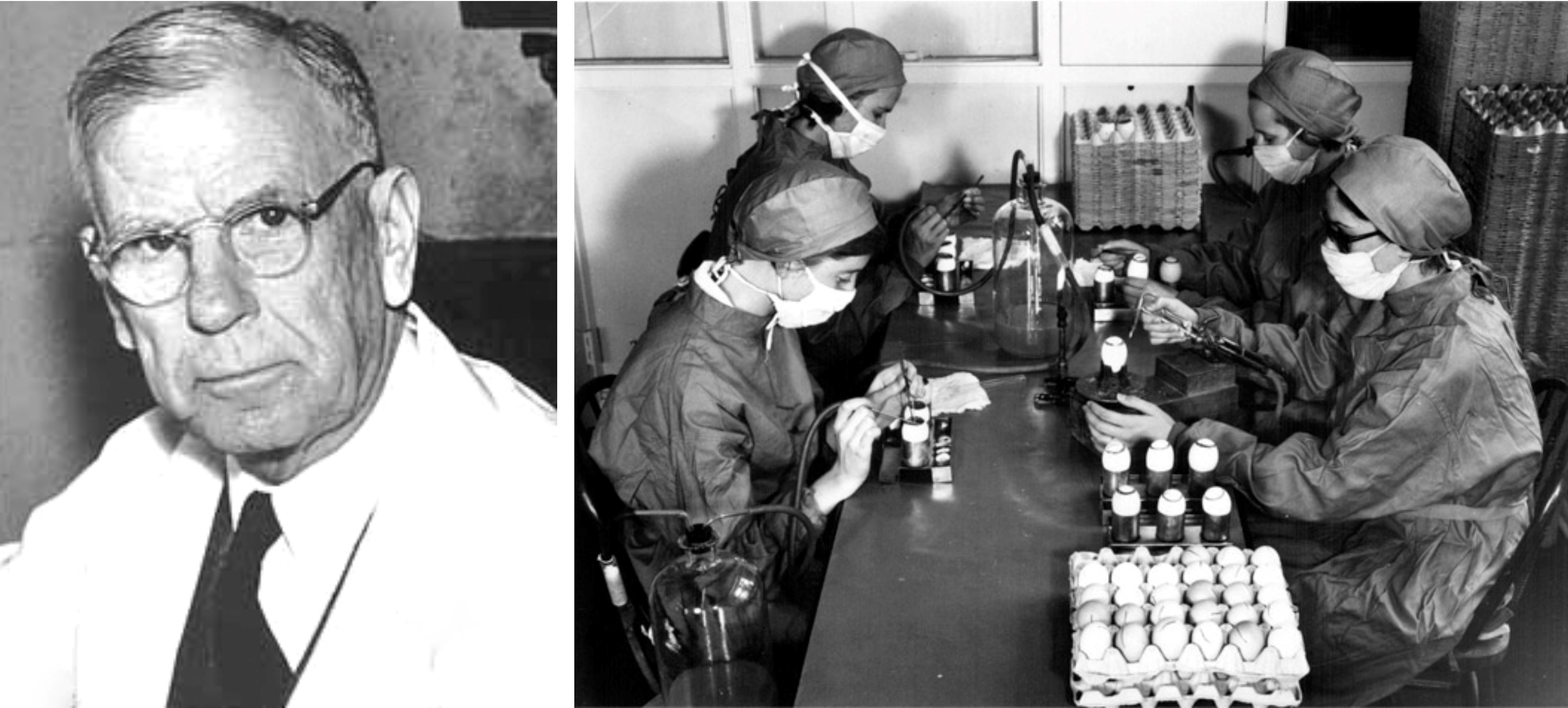

Dr. Ernest Goodpasture (left), and preparation of influenza vaccine in Connaught Laboratories in Canada, 1957 (right).

In 1919, doctors attempted to vaccinate patients against influenza, by developing a vaccine for Pfeiffer’s bacillus, but this proved completely ineffective against the wrong cause. In light of Shope and Laidlaw’s discovery of the viral nature of influenza, scientists almost immediately went to work on a new influenza vaccine. In 1931 Ernest Goodpasture, professor of pathology at Vanderbilt University, began to culture the virus in hen eggs, a technique that proved vital to developing the first experimental flu vaccines. Flu vaccines were first used by the United States military during the Second World War, and were first used publicly as early as the 1950s. While the egg-culture technology is still in some use today, as of 2012 the FDA approved growing the virus in cell cultures as well.

10. Swine Flu, or Why You Should get a Flu Shot

Former President Barack Obama vaccinated against H1N1, 2009.

In spring 2009, a new strain of the H1N1 virus emerged in Mexico and spread quickly around the globe. It affected millions of patient-cases, but the mortality rates remained lower than even seasonal influenza. Nevertheless, this seems to be a variant strain of the same virus that caused the great pandemic of 1918-1919 and cost so many millions of lives. Fortunately, scientists have been able to very quickly culture the viral strain. As a result, your annual flu shot also provides protection from the H1N1 strain of flu as well. As doctors worry about the possibility for a new pandemic, make sure you go get your flu shot.