The COVID-19 pandemic has devastated the United States—and the world—in ways that hearken back to the Great Depression of the 1930s. In this country, in 1933, 25 percent of the workforce was unemployed, another 25 percent underemployed. We haven’t reached those figures yet, but there’s a very real possibility we may arrive there soon.

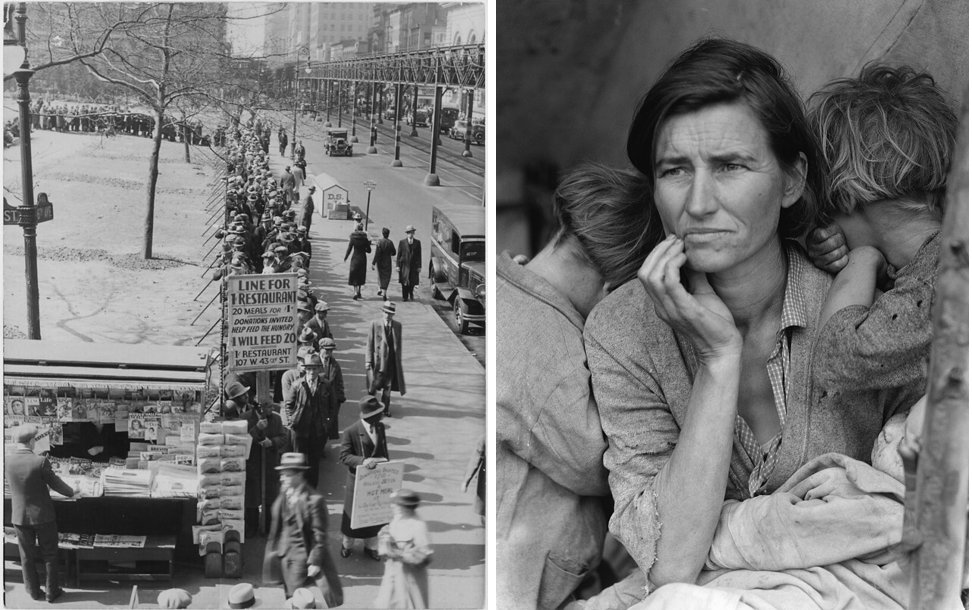

The images are haunting. We’ve all seen photos of the breadlines in the 1930s, when hundreds of unemployed workers stood in line seeing a handout. We’ve seen pictures like Dorothea Lange’s powerful photograph of a “Migrant Mother,” wondering how to care for her children. We’ve read about an unemployed family living in a cave in Central Park, in New York City.

Bread lines in New York City, 1932 (left). The famous portrait of Florence Thompson taken by Dorothea Lange in 1936 (right).

The images today are somewhat different, but the message is the same. Conditions are awful, and recently, as the number of COVID deaths surpassed 100,000, the New York Times ran a front-page story consisting solely of the names and brief obituary information of people who had died.

The New Deal of Franklin D. Roosevelt, elected in 1933, had to confront that crisis, and his response holds lessons we might well heed.

FDR won an overwhelming victory because his predecessor Herbert Hoover had been singularly unsuccessful in dealing with the ravages of the Depression.

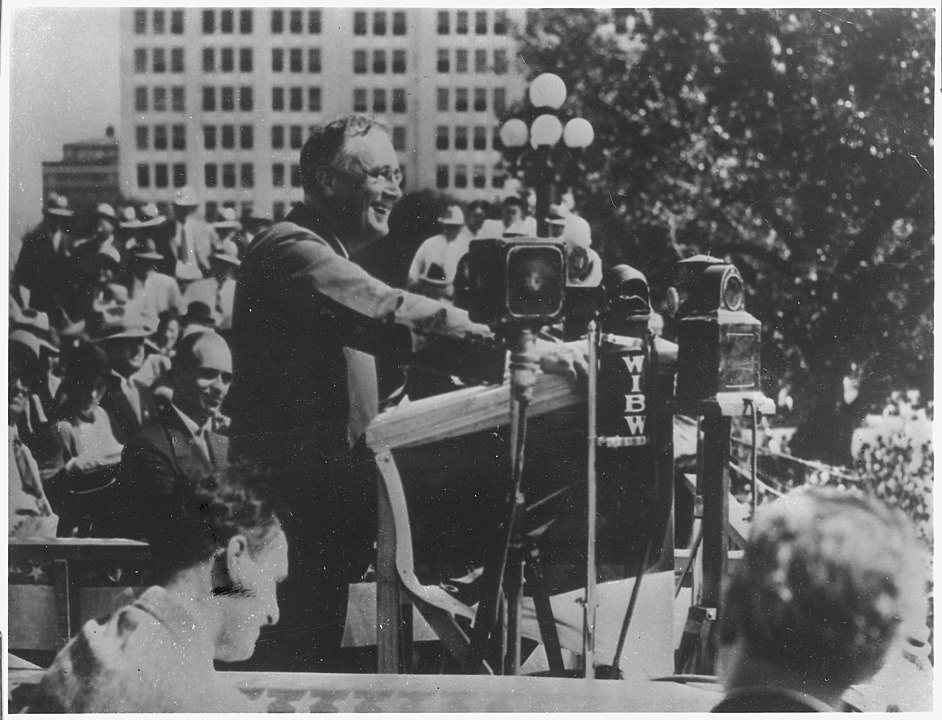

President Franklin D. Roosevelt and outgoing President Herbert Hoover on Inauguration Day in 1933.

Not everyone thought Roosevelt was up to the task. Political commentator Walter Lippmann called him “a kind of amiable boy scout” during the campaign, and on another occasion remarked, “Franklin Roosevelt is not tribune of the people. He is no enemy of entrenched privilege. He is a pleasant man who, without any important qualifications for the office, would very much like to be president.”

Such reservations notwithstanding, Roosevelt had the temperament, and the inclination, to more aggressively to address the crisis. He understood, above all, the need to convey a sense of trust to a desperate nation.

And so, in his First Inaugural, he told the suffering public not to worry. With his marvelously resonant voice, which in itself conveyed a sense of confidence, he declared, “The only thing we have to fear – is fear itself,” as he pledged to do whatever was necessary to alleviate suffering. And he did.

In his first hundred days, he saw 15 major pieces of legislation through to passage. There was a law calling for a bank holiday, to get the banking structure to function once again. There were a number of relief measures. There was the Civilian Conservation Corps, to put people back to work and do important environmental reconstruction at the same time. There were efforts to find a way to promote recovery, to get the system moving once again.

CCC workers constructing a road in what is now the Cuyahoga Valley National Park.

In this time of crisis, no one understood the new theories of economist John Maynard Keynes, who said that the key to recovery from a depression was deliberate, sustained, countercyclical government spending. Cutting taxes, Keynes said, was one way to put money into people’s pockets. But it would also work to have one group of people bury a pile of money, and another group dig it up, to get it into circulation, as a way of promoting financial liquidity.

During the 1930s, Keynes met briefly with FDR, but neither man understood the other. Roosevelt wrote to Felix Frankfurter, an adviser who taught at the Harvard Law School, “I saw your friend Keynes. He left a whole rigaramole of figures. He must be a mathematician rather than a political scientist.” Keynes, in turn, remarked that he had “supposed the President was more literate, economically speaking.”

Still, as a result of New Deal initiatives, conditions did improve. People went back to work thanks to a variety of New Deal programs. The nation built bridges and public buildings, and in the process chipped away at unemployment. Even if the effects of the Depression lingered on the legacy of those efforts remain all around us. Later, when the United States began massive spending, first for defense, then for war, the economic crisis vanished almost overnight.

So what might we learn from that experience?

First, confidence in our nation’s leadership is all important. A vast majority of the country believed in Roosevelt, and that allowed him to move ahead. Though FDR was himself a patrician, who came from a moneyed family, he had a sense of empathy for working people.

As one worker commented, “Mr. Roosevelt is the only man we have ever had in the White House who would understand that my boss is a son-of-a-bitch.” Comic Will Rogers noted, “The whole country is with him. Even if what he does is wrong they are with him. Just so he does something. If he burned down the Capitol, we would cheer and say, ‘Well, he at least got a fire started, anyhow.’” That kind of confidence is absolutely crucial in the current crisis.

Franklin D. Roosevelt in Topeka, Kansas, 1932.

Second, a sense that our leaders are eager to act to help people and not simply to score political points, is essential.

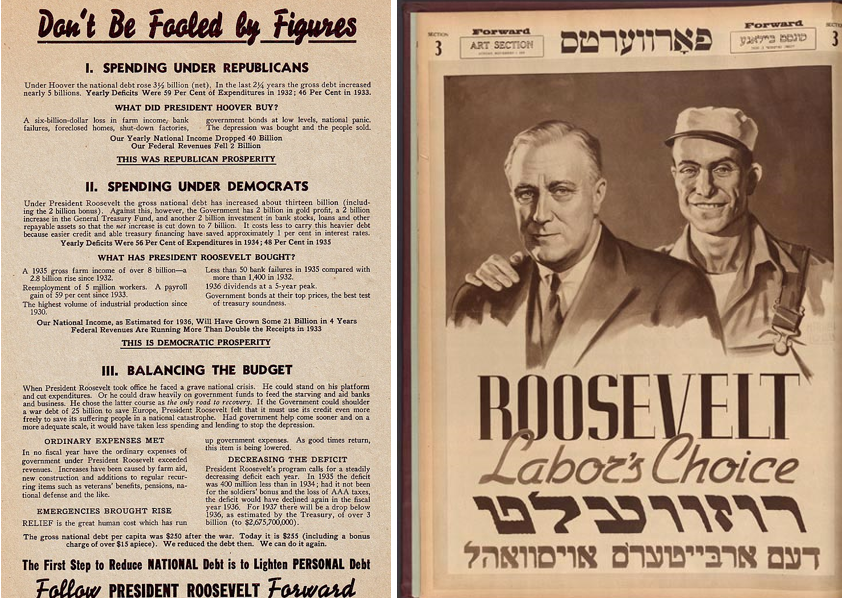

Roosevelt was a masterful politician to be sure. He understood the dynamics of the political process. In his reelection campaign of 1936, he proclaimed of the business community, “Never before in all our history have these forces been so unanimous in their hate for me—and I welcome their hatred.” Yet even as he said that, an overwhelming proportion of the public understood that he had their interests at heart.

A re-election campaign handbill for FDR issued by the DNC for the 1936 election (left). The cover of the Yiddish socialist daily "Forward," endorsing FDR as "Labor's Choice" (right).

Finally, a reliance on experts, in a pattern dating back to the Progressive era in the early years of the 20th century, helped during the New Deal and is essential today. The New Deal produced studies and reports on all manner of the nation’s problems with the belief that policy depended on finding accurate facts, and acting accordingly. It was as important then as it is now.

With good faith, and good luck, we can use these lessons from the past to create a better, and a healthier, present.