On November 2, 2018, President Trump tweeted out a movie-style poster announcing, “SANCTIONS ARE COMING.” Two minutes later the White House’s official Twitter account clarified the president’s tweet referred to renewed sanctions on Iran.

The appeal of imposing economic sanctions is obvious enough. They promise to achieve diplomatic and foreign policy objectives without the use of military force—a peaceful alternative to bloodshed and destruction. And recently, no nation has been more active in imposing sanctions than the United States. This month, historian Benjamin Coates traces the history of economic sanctions and warns that, whatever their promise, the overuse of unilateral sanctions threatens to reduce their effectiveness and even their legitimacy.

When confronted with foreign challenges, President Donald Trump has preferred one response above all others: economic sanctions.

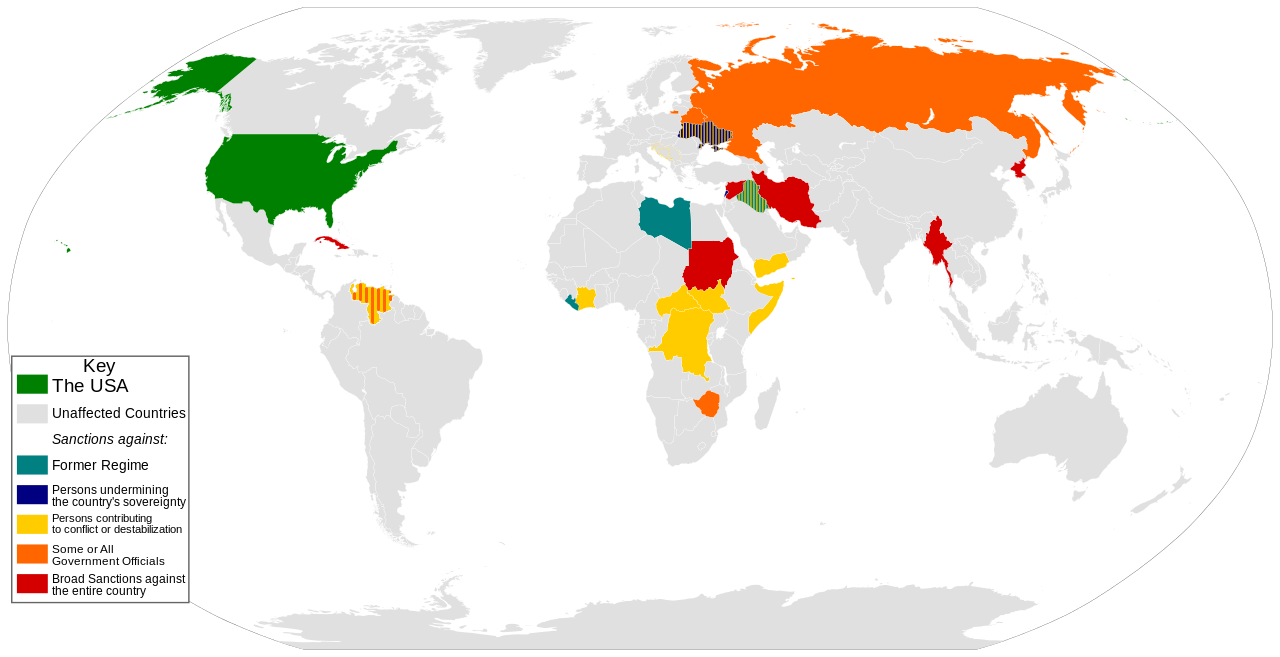

Trump has tightened embargoes on North Korea and Iran, frozen the assets of Venezuelan leaders, and targeted officials in Cuba, Russia, and Syria. His administration has added more than 1,000 individuals and companies to sanctions lists. The president has gloried in his seemingly awesome powers. Trump threatened to “totally destroy and obliterate the Economy of Turkey (I’ve done before!)” in October 2019, responding to Turkish threats against Syrian Kurds.

To an unprecedented degree, severing foreigners from trade networks and the global financial system has become Washington’s foreign policy tool of choice. Indeed, the few cases wherein the administration has held back on sanctions—as in Russia—have themselves generated controversy.

How did economic sanctions become so vital to America’s relationship with the rest of the world? The immediate answer lies in recent developments in global economics and American law that have enabled Washington to leverage its immense financial influence against all comers.

But a deeper answer requires understanding how the idea and practice of sanctions developed over the past century. Historically, sanctions have served as both the idealist’s dream and the realist’s cudgel. They have promised to the powerless a world free of war and discrimination while giving the powerful tools for domination. The legitimacy and appeal of sanctions rest on blurring the lines between these two outcomes; the more Washington turns to unilateral sanctions, the less legitimacy the practice may have.

Countries or individuals sanctioned by the United States in 2015.

The Rise of Sanctions

Economic statecraft—the use of financial or trade pressures to achieve political ends—is likely as old as trade itself. But not until the 20th century did modern concepts of international sanctions—a collective denial of economic access designed to enforce global order—become prominent.

Diplomats and military men saw economic interdependence in a different light: as a tool to supplement war. The British navy planned to defeat Germany by leveraging Britain’s dominance in merchant shipping and the dependence of global trade on London’s financial markets. Here was a plan for using economic warfare not as a way to avoid violence but as a means to intensify it, to “make war damnable to the whole mass of your enemy’s population,” as a British admiral put it.

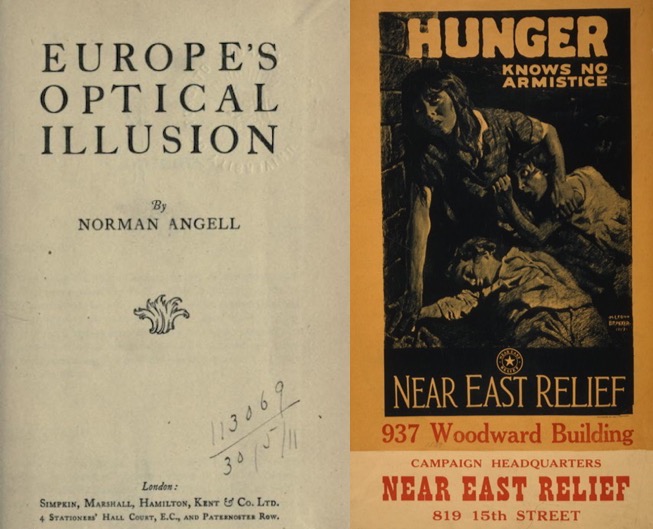

On the eve of World War I, new technologies of steam and telegraphy had made the world’s nations economically interdependent. For anti-war writers like Norman Angell, whose The Great Illusion sold more than 2 million copies between 1910 and 1913, this fact proved the folly and even impossibility of war. Any major conflict would be so costly that even the winner would fail to profit.

First published in the United Kingdom in 1909, Europe’s Optical Illusion by Norman Angell was republished a year later under the title The Great Illusion (left). The Near East Relief organization raised funds and awareness across America in response to Armenian and Assyrian genocides during World War I (right).

The British blockade took on a different meaning after the war. Britain’s throttling of German trade contributed to malnutrition that caused, by some estimates, hundreds of thousands of civilian deaths. In 1919, as the world’s leaders met in Paris to design a new postwar system of global security, they saw the “economic weapon” as a potent tool to bring aggressors to heel.

Article 16 of the League of Nations Covenant mandated an automatic and collective embargo against any nation that started an aggressive war. This would be a “terrible remedy,” said U.S. President Woodrow Wilson. Facing the cutoff of “all financial, commercial, or personal intercourse,” the argument went, nations would think twice before menacing their neighbors.

Sanctions thus served as the centerpiece of the multilateral enforcement mechanism of world peace.

The League’s Failure

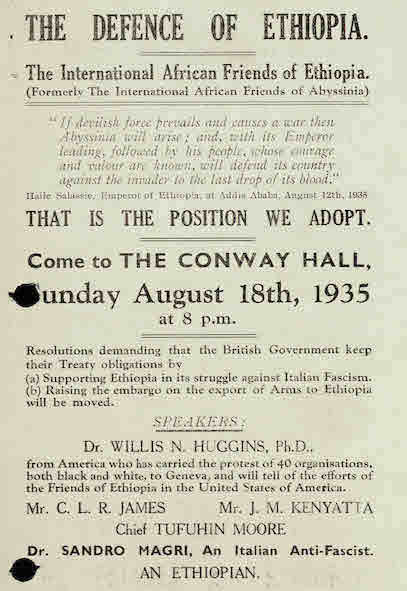

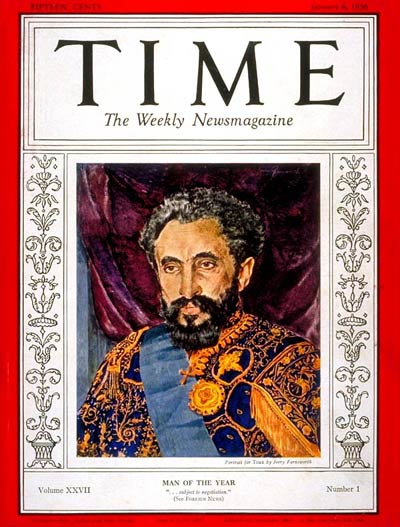

In the early 1920s, the threat of economic sanctions successfully deterred some smaller states from menacing their neighbors. But the League’s highest profile sanctions were an utter failure. In 1935 Italy invaded Ethiopia, a member of the League and one of the few African nations to have escaped previous European colonization. Ethiopian leader Haile Selassie appealed to the League for assistance.

The League voted 50-4 to impose sanctions on Italy. It banned loans and Italian imports, and it forbade exports of a range of materials including arms and metallic ores but not, crucially, oil. Since Italy lacked petroleum resources of its own, a ban on oil might have crippled its ability to wage war. But though Britain and France supported sanctions, they feared that a total embargo would drive Italy’s fascist leader, Benito Mussolini, into the arms of Nazi Germany.

Selassie condemned “the abandonment of Ethiopian independence to the greed of the Italian Government,” but to no avail. In 1936 Italian troops completed their conquest. The League’s failure reflected the difficulty of imposing sanctions, rather than the limitations of sanctions per se. But it severely damaged faith in the power of the economic weapon to prevent aggression.

Interwar Developments

Despite the League’s failures, in hindsight the interwar period proved a fertile moment for the development of sanctions.

First, the struggle on behalf of Ethiopia created an international movement committed to mobilizing opinion and economic power against racism and imperialism. Strikes and marches broke out in New York, Ghana, and India, among other places. Intellectuals penned odes to solidarity and collective action. A few Americans volunteered to fight with Ethiopian forces. Activists lobbied national governments and the League of Nations. Journalist Roi Ottley said Ethiopia’s plight had “stirred the rank and file” of black Americans more than any other event he could recall.

Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie was Time magazine’s Man of the Year in 1936.

Though these efforts failed to protect Ethiopia, they helped build durable transnational networks and popularized the notion that economic action could be a weapon of the weak—an idea further pushed by Communist organizers who supported many of these movements. As a key resolution of the 1945 Pan-African Congress in Manchester, UK, reminded workers: “Your weapons—the Strike and the Boycott—are invincible.”

The American government also transformed during this period, with the executive branch gaining new powers to unilaterally practice economic warfare during times of peace. During World War I, Congress passed the Trading with the Enemy Act (TWEA) that not only prevented trade with Germany but also authorized the seizure of German property in the United States.

Future attorney general A. Mitchell Palmer served as the Alien Property Custodian charged with managing these assets. The New YorkTimes marveled at the extent of his powers; his office served simultaneously as “the biggest trust institution in the world, a director of vast business enterprises of varied nature, a detective agency, and a court of equity.”

Alien Property Custodian executive staff in 1918.

The U.S. government asserted many new powers during the war, including control over the nation’s railroads and the power to raise an army through conscription, but these acts were intended as wartime measures and most were rescinded after the end of the war in 1918.

A provision of the Trading with the Enemy Act remained on the books, however. Section 5(b) allowed the president to “investigate, regulate, and prohibit” all financial transactions involving foreign nations. Its anodyne language belied a powerful grant of authority.

During the Great Depression, government lawyers rediscovered the Trading with the Enemy Act while combing through old wartime laws in search of presidential authority to combat the economic crisis.

In 1933, Franklin D. Roosevelt cited section 5(b) when he declared a “Bank Holiday” and temporarily banned all banking transactions. Congress then passed legislation that blessed the president’s action and amended section 5(b) to clarify that it could be invoked “during time of war or during any other period of national emergency declared by the President.” The implications of this broad authority became clear once World War II broke out in Europe.

After Nazi Germany invaded Denmark and Norway in 1940, FDR issued an executive order freezing Danish and Norwegian assets in the United States. As Nazi conquests expanded, so too did the American freeze; by 1941 it covered most of continental Europe. These actions, coordinated by a new office of Foreign Funds Control in the Treasury Department, kept millions of dollars out of Nazi hands.

They also created an important precedent: using the authority of the Trading with the Enemy Act, the president could—without Congressional approval—freeze foreign assets at a time when the United States was still at peace.

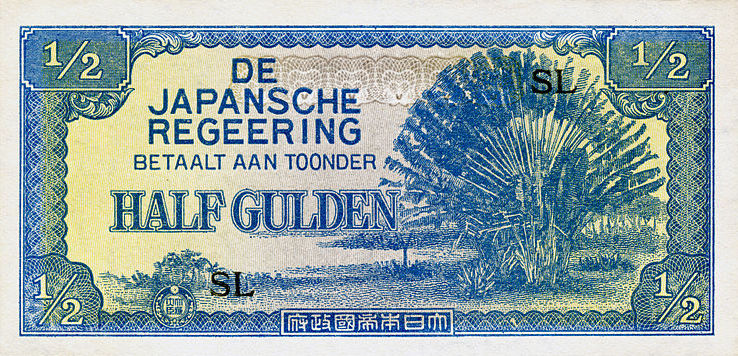

Japanese occupation currency used in the Dutch East Indies in 1942.

In July 1941, after Japan invaded Indonesia, Japanese assets in the United States were frozen, making it impossible for Japan to use its gold reserves to purchase oil and other strategic necessities. This move helped Japanese hardliners persuade the government to launch its attack on Pearl Harbor. Though FDR defended his actions as a defense against threats to freedom, the Japanese interpreted the asset freeze as an aggressive use of American power.

Sanctions to Fight the Cold War

During the Cold War, Congress passed legislation enhancing the president’s ability to use emergency provisions to impose sanctions on an array of Cold War rivals.

The logo of the U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control.

The 1949 Export Control Act provided further authority to control U.S. trade with its enemies. Washington convinced Western Europe to cooperate in limiting the exports of strategic goods to the Soviet bloc in the ultimately unfulfilled hope of constraining the Soviet arms buildup. North Korea and China faced nearly complete trade embargoes. Fearing smuggling through third countries, during the 1950s all “Chinese-type” imports—including goods like soy sauce and lychee fruit—faced scrutiny from U.S. trade officials.

A new bureaucratic apparatus, the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), emerged to administer these sanctions. Legal authorizations mounted over time, often outliving the initial reasons for their creation.

When Harry Truman declared a “national emergency” after the outbreak of the Korean War in order to activate the Trading with the Enemy Act, the emergency remained in place for a quarter century, giving Truman’s successors legal authority to expand sanctions against Vietnam, Cambodia, and Cuba.

A 2005 billboard across the street from the U.S. Interests Section offices in Havana, Cuba. The Cuban soldier calls out to the aggressive Uncle Sam, “Imperialist Sirs, we have absolutely no fear of you!” (top). President Bill Clinton visiting Hanoi in 2000 after normalization of relations between the U.S. and Vietnam (bottom).

Some sanctions—such as those aimed at Cuba—are still in place today. Imposed unilaterally or with the aid of allies, not collectively by the United Nations, these sanctions programs pursued American strategic interests.

Sanctions for Self-Determination

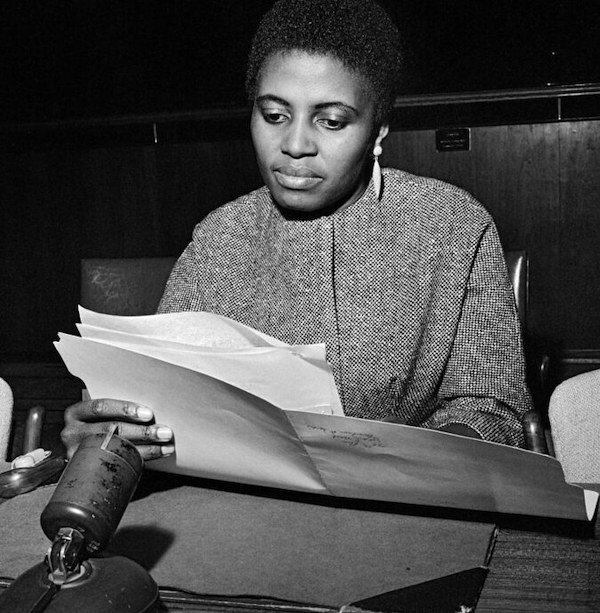

The hope of using sanctions to promote global norms reappeared in the 1960s. With the end of European empires in Africa and Asia, dozens of new nations took seats in the United Nations General Assembly. They used their growing influence to push for racial equality and self-determination.

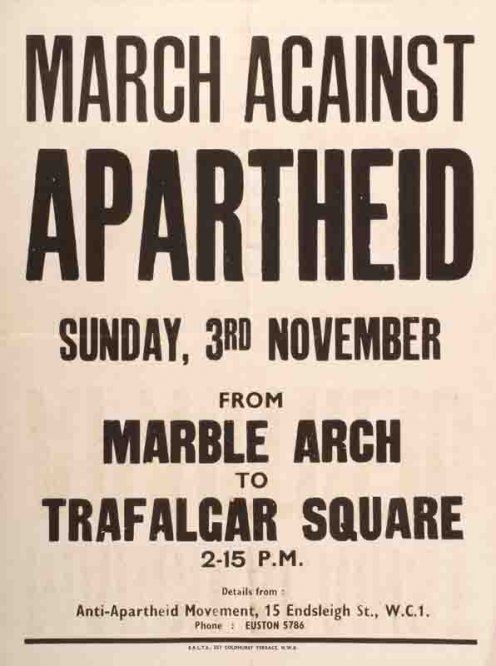

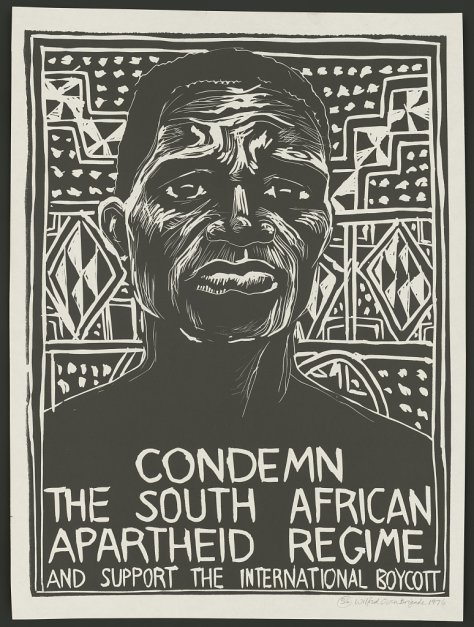

The apartheid policy of the white minority government of South Africa became an early target. For a transnational movement combining the African diaspora, white liberals, and trade unions, sanctions seemed to offer a nonviolent way to force change. An end to apartheid, said African National Congress president Albert Lutuli, would “never come willingly from the whites. Even so, it could be made to come peacefully.” In 1962, the General Assembly voted overwhelmingly to recommend an economic embargo against South Africa.

Under Article 41, the UN could impose “complete or partial interruption of economic relations and of rail, sea, air, postal, telegraphic, radio, and other means of communication, and the severance of diplomatic relations.” However only the Security Council could mandate sanctions that would be binding on all members of the UN, and without its blessing the General Assembly’s call for sanctions would remain voluntary.

The problem, for anti-apartheid activists, was that both the United Kingdom and the United States—two of the five veto-wielding members of the Security Council—opposed sanctions.

Britain fretted that sanctioning an important trade partner would damage its own economy. U.S. motivations were more complicated. In the midst of a competition with the Soviet Union for the allegiance of the third world, Washington feared alienating African governments. Yet the Kennedy and Johnson administrations also sought to placate U.S. civil rights leaders who lobbied for sanctions. And the United States was reluctant to use its veto power—it had never done so—for fear of undermining the legitimacy of international institutions.

Yet Britain was a vital Cold War ally, and to endorse the principle that a nation’s domestic policies constituted enough of a threat to international peace to warrant sanctions struck many officials as dangerous. By endorsing voluntary arms embargoes and shunting debates to commissions and study groups, Britain and the United States prevented sanctions on South Africa from coming to a vote in the Security Council.

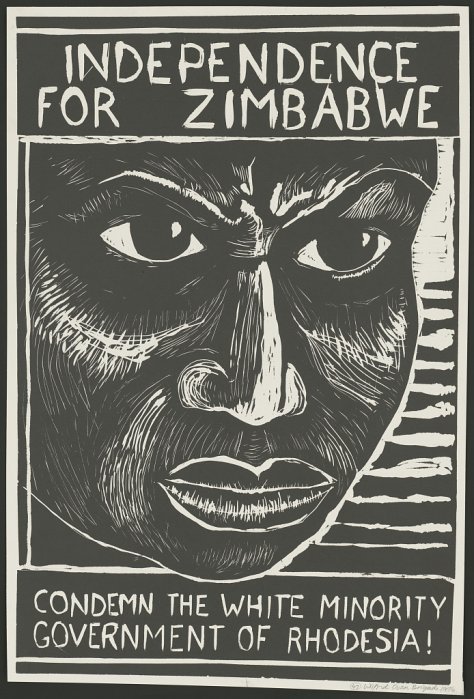

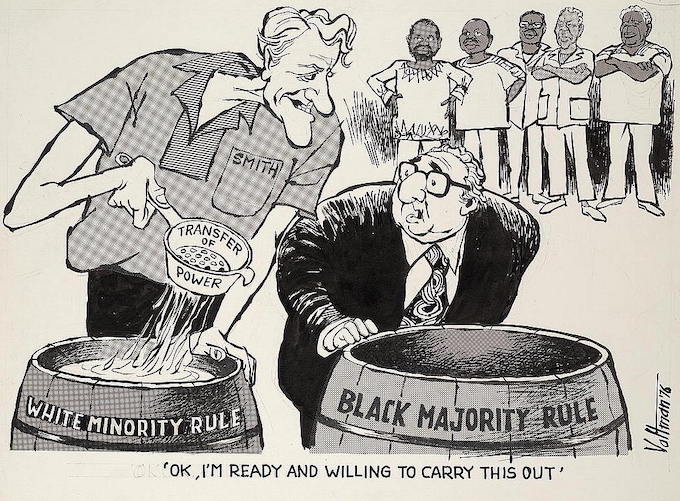

A few years later, the UN finally imposed mandatory economic sanctions for the first time. In 1965, the British colony of Southern Rhodesia declared independence from the UK. Led by Ian Smith, roughly 200,000 white Rhodesians ruled over the 4 million black majority. Rhodesian laws ensured that the white minority monopolized suffrage and property.

A 1976 poster reads, “Independence for Zimbabwe. Condemn the white minority government of Rhodesia!”

This time Britain took the lead at the UN. It had refused to grant independence to Rhodesia until the colony worked out a plan for majority rule. Incensed by Smith’s unilateral declaration of independence, British Prime Minister Harold Wilson led the UN to impose a variety of punishments culminating in mandatory economic sanctions in late 1966. Some scholars believe that Wilson pushed for sanctions mainly to head off calls for more decisive action; many African states hoped for a British military intervention.

Despite doubts that sanctions would work—sanctions “have historically (Ethiopia and Cuba) proved ineffective,” wrote one U.S. official—Washington backed its British ally. Supporting sanctions against Rhodesia was vital to maintaining America’s prestige in developing nations. “Rhodesia itself isn’t very important to us,” summarized National Security Council official Robert Komer. “But the point is that it’s critical to all the other Africans.”

Like the League of Nations before it, the UN’s first experiment with sanctions was a failure. They damaged the Rhodesian economy and isolated its government, but Smith remained in office. Extensive smuggling, especially through South Africa, undercut sanctions.

U.S. efforts wavered, especially after Richard Nixon took office. In 1970, the United Stated used its UN veto for the first time, stopping a proposal to toughen sanctions on Rhodesia. In 1971, Congress passed the Byrd Amendment allowing for the importation of strategic materials from Rhodesia—chrome, most importantly. Frustrated by the UN’s failures, opposition groups in South Africa and Rhodesia turned increasingly to armed struggle.

Expanding Unilateral Sanctions

U.S. presidents continued to sanction American adversaries. After the Iranian Revolution in 1979, when the new government of the Islamic Republic took 52 Americans hostage, President Jimmy Carter froze Iranian assets in U.S. banks to little avail.

In 1981, after the communist government of Poland cracked down on civil society groups, the Reagan Administration punished the Soviet Union by applying sanctions to prevent the construction of a gas pipeline from Siberia to Western Europe. When European companies with contracts for the work refused to comply, Washington extended the sanctions to include foreign subsidies of U.S. firms and even European companies that produced equipment under U.S. licenses. This sparked intense opposition from America’s Western European allies, forcing Reagan to lift the sanctions.

Social scientists began to question whether sanctions were even worth it. Did they create pressure on targets to change their ways, or merely generate a “rally around the flag” effect that encouraged resistance? By the early 1980s, one scholar compared sanctions to “a tiger without teeth or claws” able only to “growl a little.”

Sanctions’ inefficacy detracted little from presidents’ willingness to impose them, however. Executive power in the realm of economic warfare remained robust despite congressional attempts to crack down on presidential authority after Watergate and Vietnam.

After passing the War Powers of Act of 1973 limiting the president’s power to deploy military force abroad and the National Emergency Act of 1976 ending Truman’s 1950 declaration of emergency, Congress turned to the president’s sanctioning powers. Under the 1977 International Economic Emergency Powers Act (IEEPA), the president could no longer invoke the Trading with the Enemy Act during peacetime. The IEEPA conveyed most of the TWEA’s powers, but the president would have to declare a new emergency each time he wanted to invoke it, and Congress would have the ability to overturn these declarations through majority vote.

Reformers hoped to end the president’s ability to impose sanctions whenever he desired without explanation. However, within a decade a series of Supreme Court decisions had undermined most of the law’s limits on presidential authority, turning the IEEPA into what it was designed to prevent: a grant of virtually unlimited sanctioning power.

This power persists: in August 2019, Donald Trump explained that those questioning his authority to force American companies to stop manufacturing in China should “try looking at the Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977. Case closed!”

President Donald Trump’s August 2019 tweet about the International Economic Emergency Powers Act.

The Sanctions Decade

The end of the Cold War unlocked new possibilities for sanctions. The collapse of the Soviet Union fueled assertions that democratic capitalism represented the only successful way to organize modern society. Practically speaking, the end of the Soviet veto on the UN Security Council made it possible to use UN sanctions as a tool to enforce humanitarian projects.

The image of sanctions also got a boost when South Africa finally held free elections in 1994 after a decades-long campaign of economic pressure. Though stymied in the UN, the anti-apartheid movement had successfully convinced companies and nations to cut ties with South Africa, and while scholars still debate the precise role that sanctions played in promoting the democratic transition, advocates of sanctions felt vindicated.

Thus the 1990s became the “sanctions decade.” The UN Security Council imposed sanctions a dozen times (compared to only twice in the previous four decades—once against Rhodesia, as we have seen, and an arms embargo against South Africa in 1977).

Targets included human rights abuses in Yugoslavia, Rwanda, and Angola; Iraq’s illegal invasion of Kuwait; and support for terrorism by governments in Sudan, Libya, and Afghanistan. Sanctions once again appeared to offer hope for enforcing global norms. Yet by the end of the decade experts had come to doubt the efficacy of most of these programs.

Indeed, critics now began to highlight the costs of sanctions. In throttling economic activity, sanctions frayed alliances and hurt the most vulnerable. U.S. exporters complained about the proliferation of unilateral U.S. sanctions that closed markets to them, while allies criticized the expansion of so-called secondary sanctions, which targeted foreign firms that undermined sanctions against Cuba, Iran, and Libya.

A 1999 USA*Engage sponsored billboard meant to capture the attention of campaigning presidential candidates in Des Moines, Iowa. The image features Uncle Sam throwing a boomerang, with the caption “Unilateral Sanctions Hurting Iowa Hurting U.S.”

In Foreign Affairs, national security official Richard Haass condemned what he saw as “sanctions madness.” Frustrated U.S. exporters created a new lobbying group, USA*Engage, which sponsored a “Sanctions Reform Act” that would have limited the president’s ability to impose unilateral sanctions.

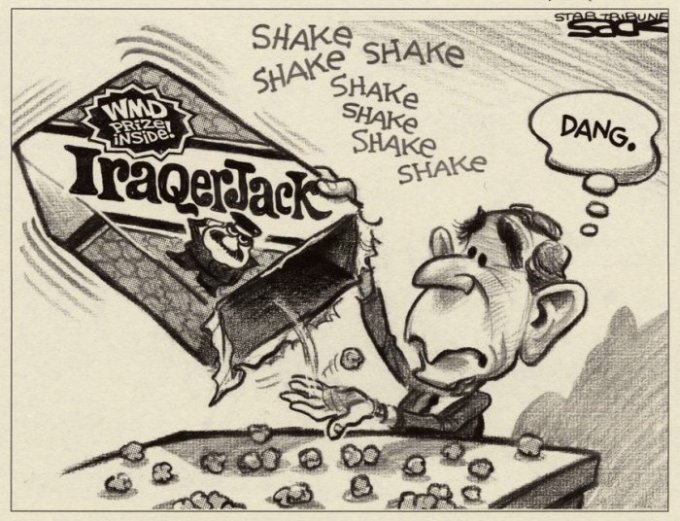

Sanctions against Iraq proved most controversial.

After the Gulf War drove Iraqi forces from Kuwait but left Saddam Hussein in power, UN sanctions programs imposed dramatic limitations on Iraq’s ability to sell oil and import goods. Designed to prevent Hussein from building an arsenal of chemical, nuclear, and biological weapons, the sanctions contributed to shortages of food and medicine for Iraqi citizens.

Critics blamed them for the deaths of half a million children. (The true number was likely smaller though still horrifying.) In response, both the UN and the United States turned to so-called “smart sanctions” that targeted the bank accounts and travel privileges of elites. Smart sanctions promised less damage to civilians, but it was unclear whether they carried enough potency to compel cooperation.

Financial Sanctions and American Power

Then came the attacks of September 11, 2001.

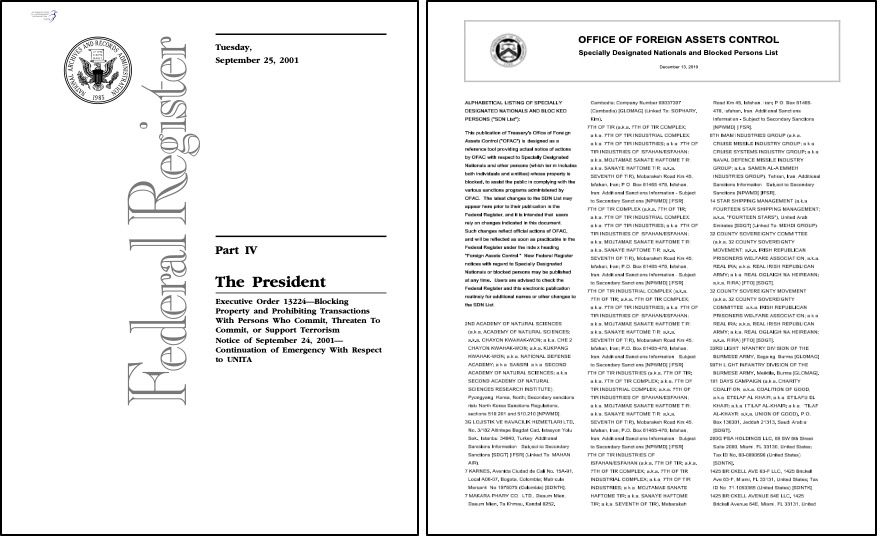

In their wake the U.S. government developed powerful new financial sanctions. Unlike traditional sanctions, which work by preventing the transit of goods and freezing accounts, financial sanctions turn private actors into enforcers. Relying on new legislation and executive orders, the Treasury Department drew up increasingly lengthy lists of “Specially Designated Nationals” (SDNs) and institutions “of primary money laundering concern.”

Executive Order 13224 - Blocking Property and Prohibiting Transactions With Persons Who Commit, Threaten to Commit, or Support Terrorism (left). Specially Designated Nationals list (right).

Being on one of these lists amounted to an economic death sentence. Not only were Americans banned from economic relationships with designated entities, but foreign firms and banks also shied away for fear of being listed themselves.

A unilateral action based on domestic U.S. law thus had global implications because the vast majority of world trade and finance is conducted in dollars and therefore passes through institutions subject to Washington’s oversight. Financial sanctions functioned, according to CIA director Michael Hayden, like “a twenty-first-century precision-guided munition.”

As the power of these new tools became apparent, the Bush, Obama, and Trump Administrations increasingly relied on them. In 2005, simply by accusing it of money laundering, the Treasury Department caused the collapse of a Macau-based bank that had been holding North Korean assets.

Iran had been under various U.S. sanctions since 1979, but after 2011 the combination of new financial sanctions and the cooperation of European allies created enough pressure to bring it to the bargaining table and promise to cease work on its nuclear weapons program in exchange for a relaxation of the sanctions.

The full power of U.S. financial sanctions became clear when president Trump withdrew from the Iran nuclear agreement in 2018 despite European protests. Not only were Iranian firms sanctioned, but any European companies doing business with them would also face financial blacklisting. Europeans grumbled—French finance minister Bruno Le Maire said it was “not acceptable” for the United States to be the “economic policeman of the planet”—but complied. Iran’s oil exports fell by more than half.

Meanwhile the SDN list continued to grow. By October 2019 it ran to 1,340 pages of names. Given such powers, Trump’s tweeted threat to ruin the Turkish economy did not seem so outlandish.

The Future of Sanctions

In their most idealistic form, sanctions promise a collective, nonviolent way to prevent human rights abuses and promote global norms. They have often failed to achieve such goals and sometimes have contributed to economic devastation that has harmed innocent people. Yet at other times, especially when imposed by international coalitions, sanctions have succeeded in changing the behavior of their targets.

America’s vast economic power has encouraged its leaders to impose sanctions unilaterally. The power of the new financial sanctions has made them especially popular of late. But their increasing use under Obama and Trump can also be read as a sign of U.S. vulnerability.

Sanctions appeal to policymakers in part because they offer a way to express disapproval and punish enemies without commitment to the kinds of overseas military operations that have recently proven both ineffective and politically unpopular. The power of U.S. unilateral sanctions relies on the monopoly of the U.S. dollar and will last only so long as that monopoly continues.

Washington’s recent reliance on sanctions has undermined their legitimacy, however. America’s rivals and allies alike have sought alternatives to the dollar-dominated financial exchange system. Russia, for instance, has moved to create a new regional financial exchange. Europeans are experimenting with barter-based systems to facilitate non-dollar trade with Iran. Venezuela floated a blockchain-based currency.

Tourist in 2012 holding Iranian currency (rial) in Ardabil, Iran.

So far none of these challenges has borne fruit. But so long as sanctions are seen as American power politics rather than enforcement of collective norms, their challengers will multiply. Unless U.S. leaders convince other nations to cooperate, they may be forced to find alternatives to sanctions as a central tool of American foreign policy.

Baer, George. Test Case: Italy, Ethiopia, and the League of Nations. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press, 1976.

Baldwin, David, and Robert Pape. “Evaluating Economic Sanctions.” International Security 23, no. 2 (1998): 189–98.

Coates, Benjamin A. “The Secret Life of Statutes: A Century of the Trading With the Enemy Act.” Modern American History. 1, no. 2 (2018): 151-172.

Cortright, David, and George Lopez. The Sanctions Decade: Assessing UN Strategies in the 1990s. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2000.

Dobson, Alan P. US Economic Statecraft for Survival, 1933-1991: Of Sanctions, Embargoes and Economic Warfare. London: Routledge, 2004.

Gordon, Joy. Invisible War: The United States and the Iraq Sanctions. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010.

Hufbauer, Gary Clyde., Jeffrey J. Schott, Kimberly Ann Elliott, and Barbara Oegg. Economic Sanctions Reconsidered, 3rd ed. Washington, DC: Peterson Institute for International Economics, 2007.

Irwin, Ryan M. Gordian Knot: Apartheid and the Unmaking of the Liberal World Order. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Rowe, David M. Manipulating the Market: Understanding Economic Sanctions, Institutional Change, and the Political Unity of White Rhodesia. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2001.

Stevens, Simon. “Boycotts and Sanctions against South Africa: An International History, 1946-1970.” PhD. Dissertation. Columbia University, 2016.

Zarate, Juan. Treasury’s War: The Unleashing of a New Era of Financial Warfare. New York: PublicAffairs, 2013.