To mark the 100th anniversary of American military involvement in World War I, Origins asked three distinguished historians to address the question: What do you think is the most important legacy of the First World War? Bruno Cabanes describes how the sheer scale of death and destruction changed our way of mourning and remembering. Jennifer Siegel follows the money to examine how the war re-arranged the balance of financial power in the world. And Aaron Retish explores how the war not only made possible the Bolshevik Revolution but defined the characteristics of the Soviet State.

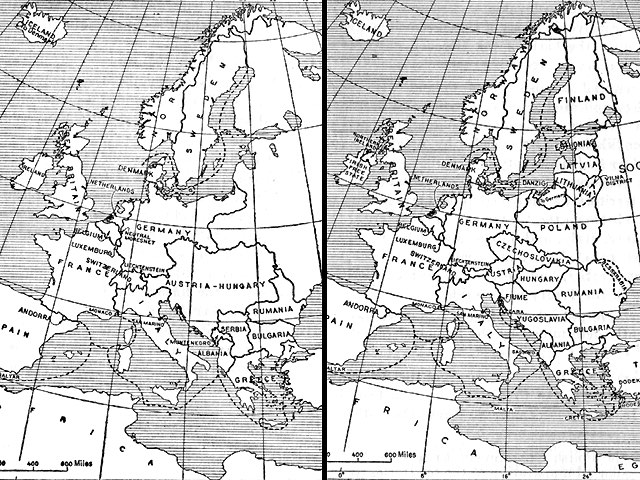

Since August 2014, events of all kinds across the globe have marked the centennial of the Great War (1914-1918) . That cataclysm brought to a crashing demise the world of the late 19th century.

By war’s end, the Russian, Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman, and German empires that had dominated Europe for centuries no longer existed, broken up into a new constellation of nation-states, fledgling democracies, and political experiments such as Bolshevik communism. Much of Europe lay in tatters and virtually an entire generation of men on both sides of the conflict had been killed, maimed, or otherwise harmed—and the damage extended to Europe’s many colonies and former colonies.

The 20th century began with the First World War and the war’s consequences continue to shape our world today. When ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi announced to the world that the group’s drive to establish a new nation would not stop “until we hit the last nail in the coffin of the Sykes-Picot conspiracy,” many had surely forgotten that the boundaries of the modern Middle East were drawn during and after World War I.

Americans came late to the war. Troops with the American Expeditionary Force landed in Europe early in the summer of 1917 but it wasn’t until late October that they saw sustained fighting on the front lines.

We hope you enjoy this multi-perspective look at how the First World War changed—and continues to change—our world.

The Lost Generation: Keeping Watch over Absent Bodies

by Bruno Cabanes

The First World War was a crucial moment in western cultures of death and mourning. Of the male population between ages 15 and 49 at the war’s outbreak, about 80% in France and Germany, between 50% and 60% in Britain and the Ottoman Empire and 40% in Russia were mobilized. Of these men, 10 million were killed, with Serbia losing 37% of its conscripts, Romania 26%, and Bulgaria 23%.

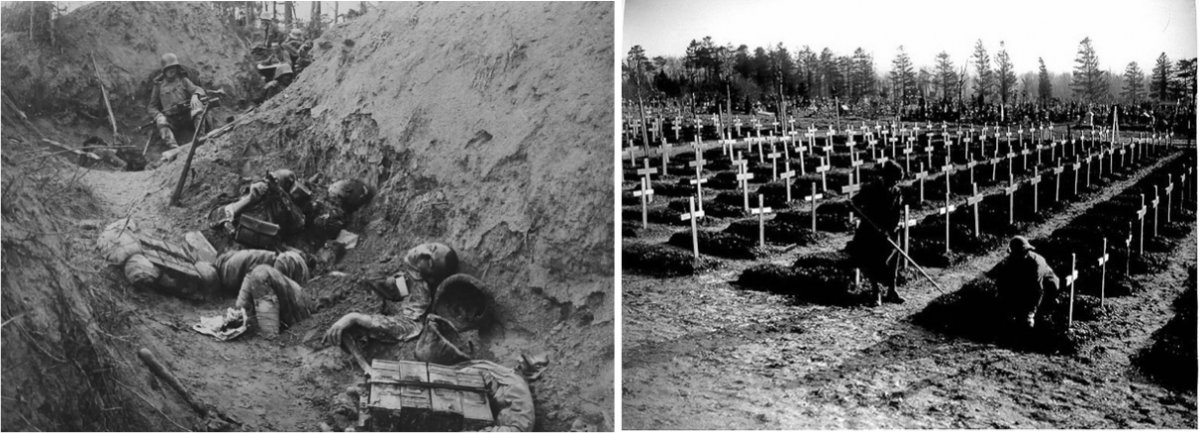

Italian soldiers killed in a trench in Slovenia during World War I (left). Members of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps tending the graves of British soldiers in a cemetery in Abbeville, France in 1918 (right).

In Europe, and in Australia due to the number of men who enlisted as volunteers in the ANZAC forces, every part of the social structure was plunged into a period of bereavement. This phenomenon is difficult to understand in the United States, where World War I is not written into family history in the same ways as World War II or Vietnam. Almost a third of the 10 million combatants who died in World War I have no known grave—the same percentage of people whose deaths on 9/11 left no trace whatsoever.

As early as 1915, losses of life from the war were traumatic. For the first time in modern history, death in combat reversed the normal succession of generations, and not on a limited scale. It did so for an entire generation: the “Lost generation,” “la génération perdue.”

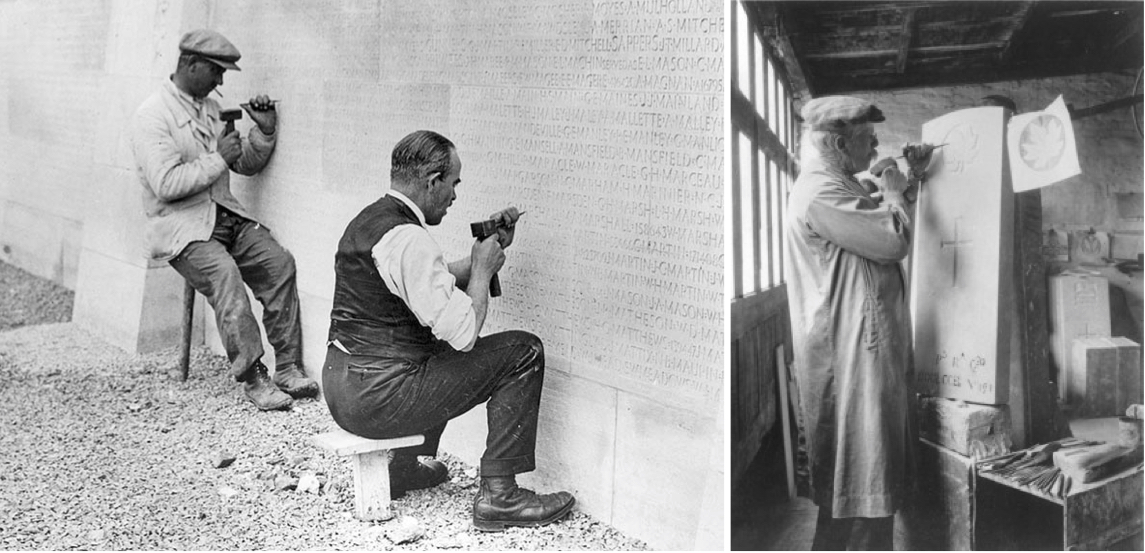

Between 1925 and 1939, workers carved the names of Canada’s Great War dead into the Vimy Memorial in France (left). A worker for the Commonwealth War Graves Commission would spend a week carving a regimental badge onto a headstone (right).

In Great Britain, 30% of men who were between the ages of 20 and 24 in 1914 were killed during the war. Feminist writer Vera Brittain, who wrote Testament of Youth about losing her fiancé Roland, her brother, and several friends to the war, later described her postwar life as “threatened perpetually by death,” and happiness as “a house without duration … built upon the shifting sands of chance.”

|

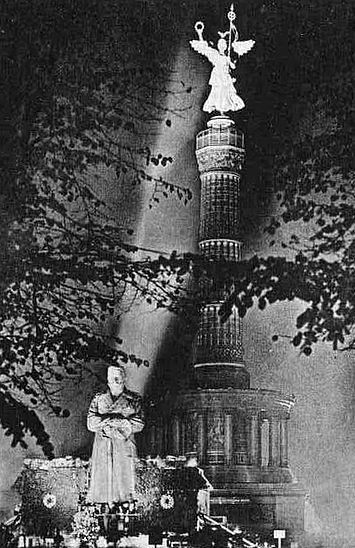

| Nagelfiguren, war memorials made from iron nails embedded in wood, became popular in Germany and Austria. The largest nagelfiguren was a statue of General Paul von Hindenburg in Berlin in 1915. |

A significant number of these young men from the lost generation went missing in action, and when they did exist, bodies were almost never returned to families, at least not until the early 1920s. For families without a body to bury, there was no ceremony. There were no traditional rites to perform, leaving survivors in a permanent state of limbo.

Grief is an individual journey, but World War I changed the rituals of collective mourning forever. The first major commemorative invention was the moment of silence—a two-minute silence in the case of Great Britain and the Commonwealth.

The idea is said to have originated with a Melbourne journalist, in a letter to the London Evening News. This was brought to the attention of King George V, who issued a proclamation calling for the “complete suspension of all our normal activities” for two minutes “at the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month” so that “in perfect stillness the thoughts of everyone may be concentrated on reverent remembrance of the Glorious Dead.”

Moments of silence are now observed on all sorts of solemn occasions. In Israel, on Yom Hashoah (the Day of Remembrance of the Holocaust, instituted in 1951), the sound of a siren stops traffic and pedestrians throughout the country for two minutes. A three-minute silence was observed worldwide 10 days after the Asian tsunami of 2004, as it had been after 9/11.

The unveiling of the Whitehall Cenotaph, a war memorial in London, England, in 1920 (left). American Secretary of War John Weeks, President Calvin Coolidge, and Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Arlington, VA in 1923 (right).

Since World War I, silence has been widely used as a language of commemoration and mourning: the Great War, the first of many cataclysmic events of the 20th century, was a war beyond words.

With so many soldiers having no known grave, both nations and communities also had to create new spaces where veterans and families could gather and commemorate their dead. In the decades after the war, tens of thousands of war memorials were erected throughout the world, serving as both symbolic graveyards for those who had lost their lives in the conflict and transitional spaces for grieving survivors.

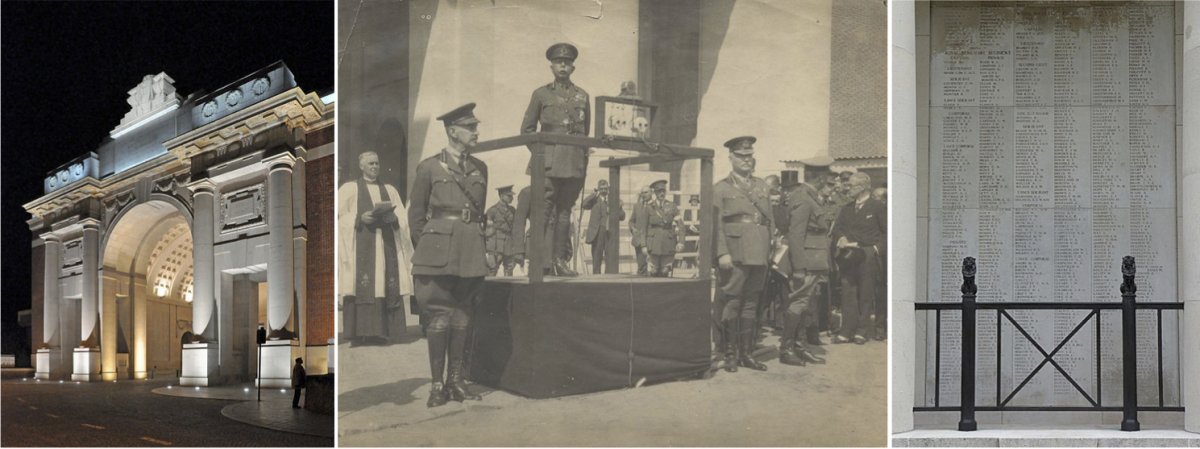

The Menin Gate Memorial to the Missing in Ypres, Belgium was for British and Commonwealth soldiers killed in World War I with unknown resting places (left). Brigadier General Francis Dodd of the Canadian Expeditionary Force unveiling the Menin Gate Memorial in 1924 (center). One of the many panels inside the Menin Gate Memorial that lists the names of missing British and Commonwealth soldiers (right).

Parents, widows, orphans, and friends often made the pilgrimage to World War I battlefields to reconnect with their loved ones. Others visited the tombs of the unknown warriors, under the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, in Westminster Abbey in London, at the Arlington cemetery in Washington D.C., and in other symbolic places around the world. It was only in 1993 that an Australian soldier was repatriated and entombed in the Hall of Memory at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, and even more recently that a tomb of the unknown warrior was created in Canada (2000) and New Zealand (2004).

In 1944, General Charles de Gaulle laid a wreath at the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior at the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, France (left). A guard of honor at New Zealand’s Tomb of the Unknown Warrior during Armistice Day in 2012 (right).

Like the moment of silence, such memorials had the capacity to reflect whatever meanings one might ascribe to World War I, and the successive meanings of the Great War throughout the century.

Finally, in the wake of the Great War, names of dead became a distinctly modern form of commemoration. Names sometimes stood over bodies, but they more often stood for bodies, for the many missing in action – like on the enormous memorial built at Thiepval, which bears more than 73,000 names of combatants from Great Britain and the Commonwealth who died in the Battle of the Somme with no known grave.

The Thiepval Memorial to the Missing of the Somme in France is dedicated to the over 70,000 British and Commonwealth soldiers killed at the Battles of the Somme (1915-1918) whose bodies were never found or identified. Their names cover the tall white bands at the bottom of the memorial (left). The Vietnam Veterans Memorial with the Washington Monument in D.C. in the background (right).

American architect Maya Lin, who designed the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington D.C. in 1982, has often acknowledged a conceptual debt to Edwin Lutyens’ Memorial to the Missing of the Somme.

“The strength of a name is something that has always made me wonder at the ‘abstraction’ of the design,” she wrote. “The ability of the name to bring back every single memory you have of that person is far more realistic and specific and much more comprehensive than a still photograph which captures a specific moment in time or a single event or a generalized image that may or may not be moving for all who have connections to that time.”

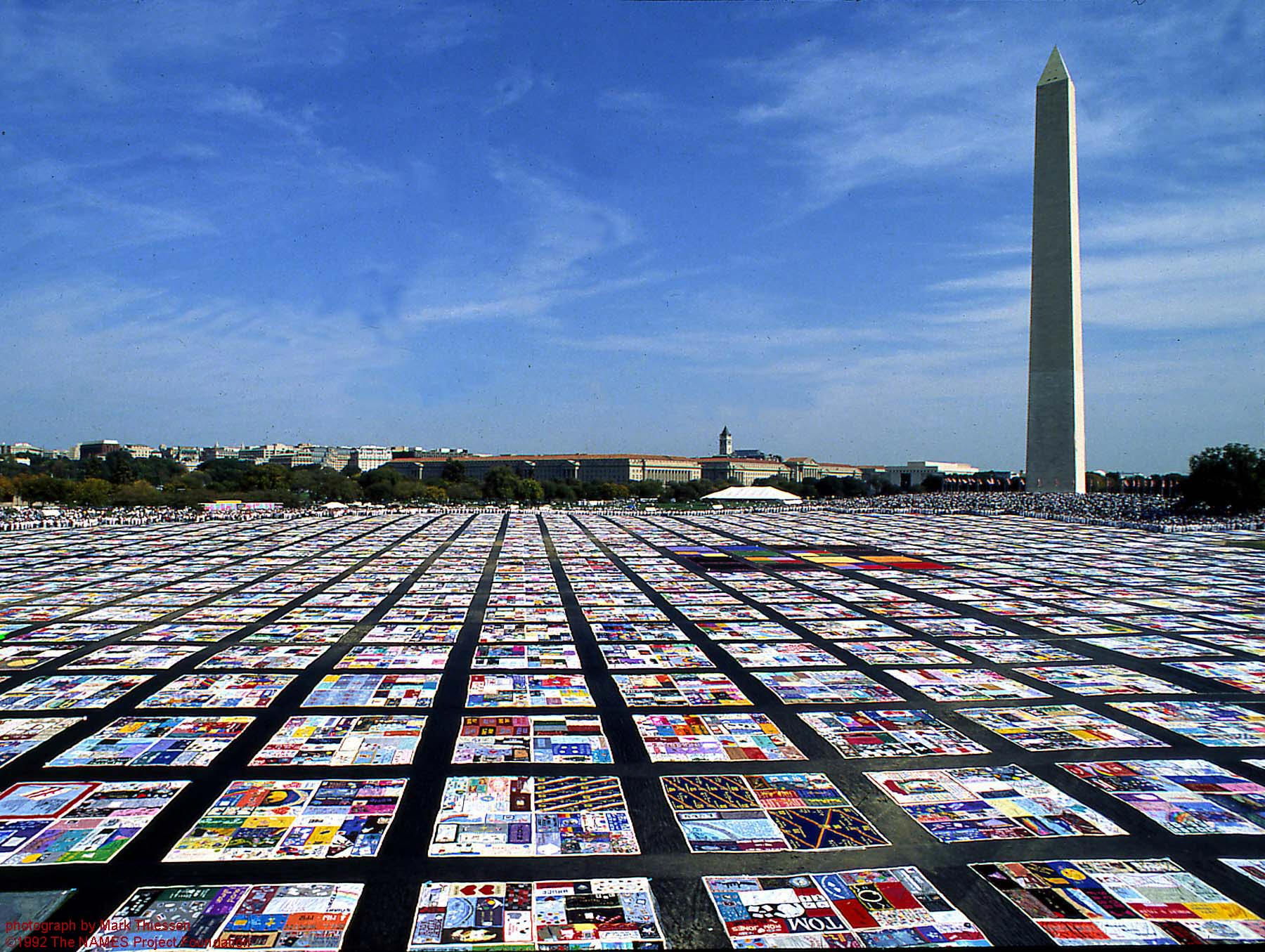

The AIDS Memorial Quilt on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. in 1987.

Turning numbers into names: this act of resistance to the dehumanizing effects of catastrophe is one of the most moving legacies of World War I. It is a legacy that would later influence the commemoration of the Holocaust, the Vietnam War, and the AIDS epidemics, with the NAMES Project Memorial quilt conceived in 1985 by Cleve Jones.

|

| Charles, Prince of Wales, laying a wreath at a Rememberance Day Service at the Cenotaph in 2017. |

The profusion of war memorials, the moment of silence, the creation of the unknown warrior, and the centrality of names and naming in the commemoration of mass death: these commemorative practices still shape our world.

As early as the summer of 1914, the massacres of the Battle of the Frontiers and the Battle of the Marne augured a major demographic and ritual crisis. None of the bodies of the dead were returned to families. But in many villages, neighbors continued to assemble in the houses of the dead to support grieving families.

The French writer Jean Giono described such a scene in a passage from his novel Le Grand Troupeau (To the Slaughterhouse): “Everybody from the plain was there. They had all come, the old men, the women and the little girls, and they were sitting stiffly on the stiff chairs. They said nothing. They sat on the edges of the shadows … They were coming, they were all there in the farm’s big room with its cold fireplace. They were there stiff and silent, keeping watch over the absent body.”

The very experience of death and of mourning had changed.

The Emergence of a (Financial) Superpower

by Jennifer Siegel

The war that erupted in August 1914 was not one for which any of the belligerent powers were fully prepared, on any level. But from a financial perspective, they were prepared least of all.

Combat predictions prior to the outbreak of war had suggested that it would be an offensive, mobile war that would be over in a matter of months, if not weeks. Instead, the combatants in World War I quickly found themselves embroiled in a conflict that proved to be a long, drawn out, costly war of attrition. Its costs were unprecedented and certainly unpredicted.

A run on a bank in Berlin, Germany at the outbreak of war in 1914.

Calculations of the total cost of the war vary considerably based, in part, on whether or not the calculations account accurately for wartime inflation. But by any measure, this war was astronomically expensive.

One set of calculations, for example, gives the total war expenditure (the increase in public spending over and above the norm for before the war) for Britain, France, Russia, the United States and their allies as $147 billion dollars (approximately $2.4 trillion today) and the costs for the principal Central Powers of Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, Germany, and the Ottoman Empire as $61.5 billion ($997 billion today).

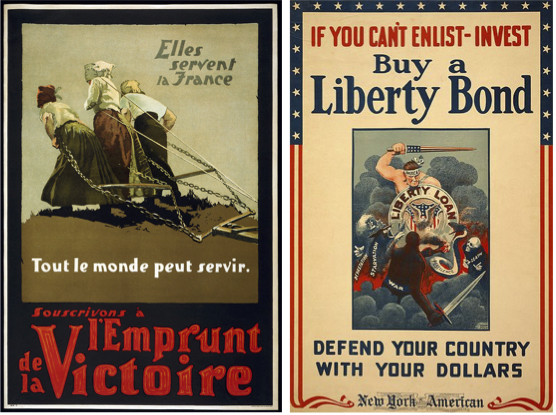

A 1918 poster calling upon Canadians to buy Victory Bonds to support the war effort (left). A 1918 poster imploring Americans to buy Liberty Bonds (right).

This was a war in which the traditional sources of strength—population, territory, GNP, colonial power—were not as important as the ability to raise revenue, either through the strength of the existing economy or through the alliances and relationships.

The war also was financed almost entirely on credit, through the issuance of short-term treasury bills (which ultimately stoked inflation), through publicly issued and domestically purchased war bonds, and through foreign borrowing. All combatants were confident that the bulk of the war’s expenses could be deferred through short-term borrowing and paid after the war was over, mostly through indemnities and reparations extracted from the defeated powers.

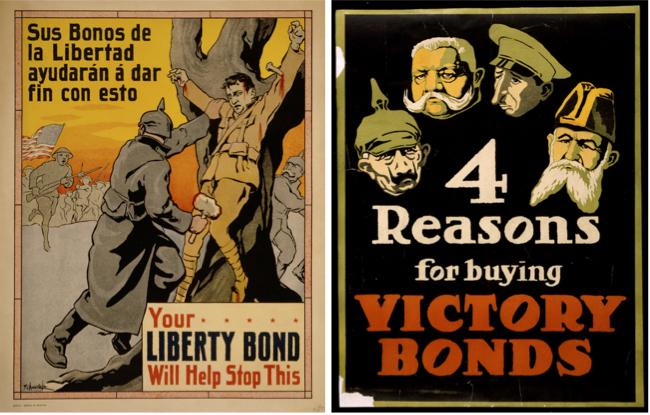

A 1917 poster printed by the U.S. government in the Philippines with English and Spanish text urging the purchase of Liberty Bonds (left). A 1917 Canadian poster with the caricatured heads of German leaders and military commanders (right).

Germany, the financial powerhouse of the Central Powers, launched an attempt to float a major loan in New York in 1914. When that failed, the German leadership recognized that the resources to fight would have to come from within their own alliance bloc. On a practical level, this meant all the members of this alliance relied on issuing domestic war bonds and on foreign credit procured from their German ally.

For example, Austria-Hungary, borrowed an average of 100 million Marks per month (roughly $325 million today) from Germany throughout most of the war. By October 1917, Austria-Hungary owed Germany more than 5 billion Marks (roughly $16.25 billion today). Germany also loaned the Ottoman Empire more than 4.7 billion Marks over the course of the war.

Austro-Hungarian posters from 1916-1918 asking citizens to take out war loans to support the war effort (top left), (top center), (top right), bottom left), (bottom second from left), (bottom third from left), (bottom right).

In order to pay for the loans, the German government issued short-term war bonds, the Kriegsanleihe, every six months, raising close to 100 billion marks. However, those bonds did not meet Germany’s total direct war-related expenses, which came to nearly 150 billion marks, not to mention the interest which continued to accumulate on the Kriegsanleihe and other German government debt.

For the Allied and Associated Powers, things were both more complicated and far simpler. This alliance bloc enjoyed the advantages that came with the inclusion of the economic resources of the British Empire and the London money market. Over the course of the war, Britain loaned approximately £1,852 million (nearly $130 billion today) to its allies and Dominions.

Tsarist posters from 1916 urging Russians to support the war by buying war bonds (top left), (top middle), (top right), (bottom left), (bottom second from left), (bottom third from left), (bottom right).

However, those millions did not come from British reserves. In addition to Britain’s own war bonds and the contribution of direct and indirect taxation to Britain’s war effort, the British government borrowed from overseas a total of £1,365 million by the end of the fiscal year 1918-19. Seventy-five percent of that sum came from the United States. Through this process, Britain’s allies were able to take advantage of the continued strength of British credit on the international market, borrowing at rates far better than those they could have received on their own.

The extensive borrowing by Britain and its allies from the United States, however, underwrote and underscored the great transition of financial power from Europe to the United States that took place during the course of the First World War.

A 1918 poster urging Austrians to contribute funds to the war effort (left). A 1918 poster from the Baruch Strauss Bank urging Germans to buy the 8th German war bonds (middle). A 1918 poster from the Baruch Strauss Bank urging Germans to buy the 9th German war bonds (right).

All this purchasing and borrowing from the United States served the ancillary purpose of linking the U.S. economy directly to the allied cause—to excellent effect, it turned out, as the United States ultimately joined the fray on the Allied side in the spring of 1917, thanks in part to these financial links.

By the end of the war, the United States had extended over $10 billion (approximately $162 billion today) in war loans to their allies, a significant portion of which was required to be spent on purchases made in the United States. This requirement was a tremendous boon to U.S. industry and production, helping to solidify U.S. economic primacy in the future.

A 1917 poster asking for “Peace through victory” with the purchase of war loans from Bankhouse Schelhammer & Schattern (left). A 1917 Austrian poster urging contributions to the war loan (middle). An appeal for the purchase of war bonds from the Oesterr Bank in 1918 (right).

The result was a distinct decline of the European economic position in comparison to that of the United States. Over the course of the war, the European nations were transformed from creditor nations into debtor nations. When the debt of the Allied nations to the United States was funded in 1922, the total indebtedness amounted to $11,656,932,900 ($169,848,451,000 today).

The plight of the Central Powers is best exemplified by Germany, which, in addition to the vast debt accumulated in the process of fighting the war, was saddled with the equivalent of some $33 billion dollars of postwar reparations payments to the victors.

A 16th century soldier waving the Austro-Hungarian flag on a poster appealing for war loans in 1916 (left). A German pilot on a 1918 poster for war loans with the upper text asking “and you?” (middle). A 1917 poster urging Germans that the best savings bank is the war loan (right).

The fulcrum of the world financial system had clearly shifted from Europe to New York, from the pound sterling to the U.S. dollar.

As a further consequence of the war, European investments in non-European countries diminished, curtailing the ability of European countries to influence economic and political development elsewhere. Since one of the preferred methods of achieving world power was cultivating an informal imperial relationship—wherein a country was influenced instead of colonized—this was a big loss for the Europeans.

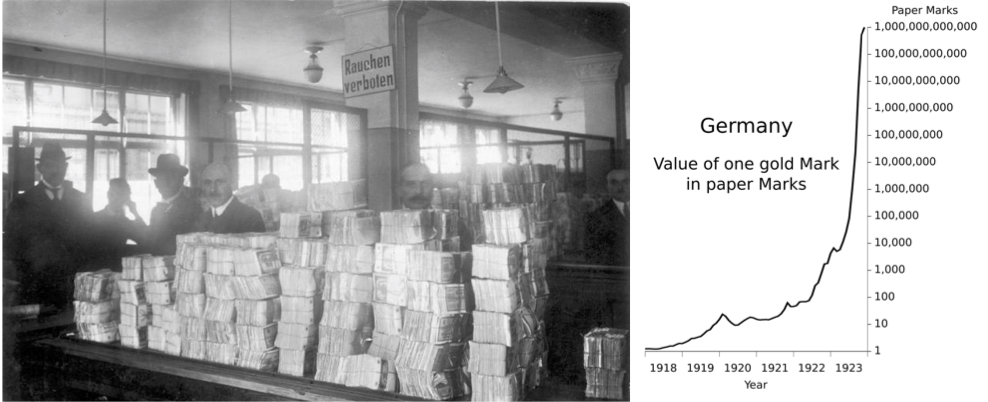

By 1923, German paper currency had become so devalued that large stacks were required even for small purchases (left). A chart showing the hyperinflation occurring in Germany after the war (right).

In addition, the reorientation of the European belligerents’ economies towards war production had completely shut off their export trade to the non-European parts of the world. The result was that these non-European nations became much less Europe-oriented, particularly as U.S. trade, manufacturing, and investment often picked up the slack. These nations were forced to start their own processes of industrialization, since they could no longer rely on industrial imports from Europe.

Thus, the First World War gave a big push to the limited industrialization of the non-industrialized world. And the crippling burden of post-war debt ensured that the economies of the traditional European imperial powers were unable to rebound easily to reassume their dominance over global trade.

The war signaled the end of the European-dominated world financial system. The extraordinary amount of postwar debt overwhelmed the global economy and the international monetary system, helping to contribute to the climate in which the world economic crisis developed.

When World War II erupted barely more than 20 years later, the tensions behind this second global conflict had been nurtured in no small part by the economic instability engendered by the financial costs and methods of World War I.

Remembering and Forgetting in Russia

by Aaron B. Retish

Until recently, a visitor to Russia would have had a hard time finding any memorial to the Great War. Unlike in the United States, Great Britain, or even Germany, in Russia there was no official memorialization of its soldiers or the immense sacrifice of the population. It could seem as if there was no lasting legacy in Russia of the First World War.

The Soviet state remembered the war as an “imperialist” conflict that exposed the political despotism of the tsar and exacerbated economic cleavages among the classes. Instead of memorials to soldiers, the Soviets put up homages to Lenin and other revolutionary leaders that can still be found in even the smallest towns.

The Soviet drive to enshrine their revolution involved erasing or hiding the memory of World War I. Even historians in the West studied the war on the Eastern Front as a political and social prelude or historical speed bump to revolution.

The two Russian Revolutions of February and October 1917 were certainly the most significant legacy of the First World War in Russia. And they irrevocably changed world history, bringing to life the planet’s first officially socialist state. In this way, I agree with the Soviet narrative, but not just because the wartime conditions set the stage for the October Revolution.

Rather, the legacy of the war in Russia was how it mobilized and politically radicalized the subjects of the Russian empire and created many of the characteristics of the Soviet system. World War I established state practices that would endure for years and the experience of the war transformed how people related to their nation and institutions of power.

A demonstration in St. Petersburg, Russia during the February Revolution. The banners read: “Feed the children of the defenders of the motherland” and “Increase payments to the soldiers’ families—defenders of freedom and world peace.”

Russia was not destined to lose the war nor descend into revolution. The tsarist state mobilized much faster than Germany expected, scuttling its foes’ dreams of avoiding a two-front war, and was in fact on the verge of quickly defeating Germany in August 1914 after successfully invading Eastern Prussia. Despite colossal setbacks the following years, Russia actually out-produced Germany in arms by 1916.

The people mobilized for war and became part of the war effort beyond what the tsarist administration dreamed. Peasants, local administrators, and townspeople alike answered the call to colors. Those on the homefront gave up grain and horses to the war effort, helped to guard POWs, and cared for Russia’s massive numbers of refugees when the war turned bad.

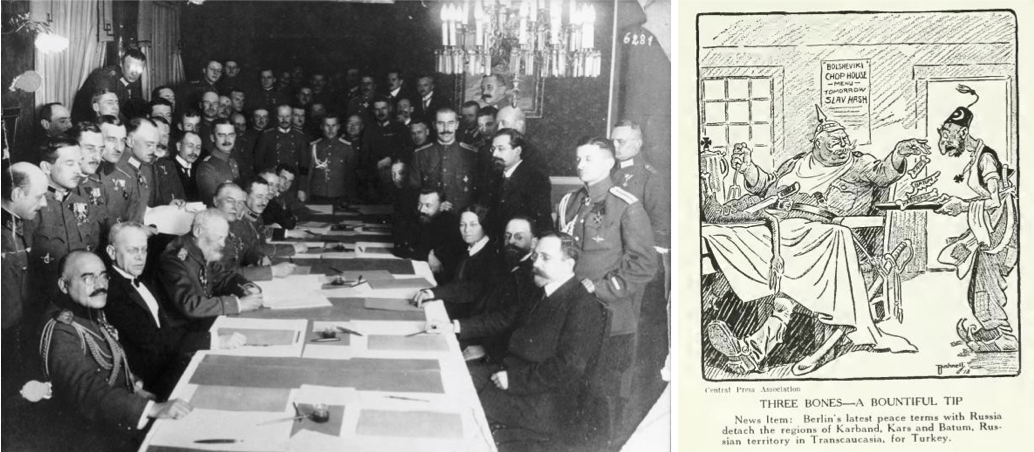

The signing of the Russian-German armistice in late 1917 (left). A 1918 cartoon depicting Germany dismembering Russia and passing on several territories to Turkey after the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (right).

Russia was like the other belligerent countries that confronted food and fuel shortages and growing resistance to the war effort from soldiers and civilians alike. Yet, even with growing war weariness, the people remained mobilized. They did so because they were patriotic and felt tied to the nation, fighting for mother Russia and not necessarily the scandal-ridden tsar.

Mobilization and the national spirit of the war unleashed a democratizing force. The unrest in Petrograd in February 1917 that led to the downfall of the tsarist regime was initiated by people who were part of the war effort, led by female workers and soldiers’ wives. The people, politicized and empowered by the war, demanded economic and political rights that carried through 1917.

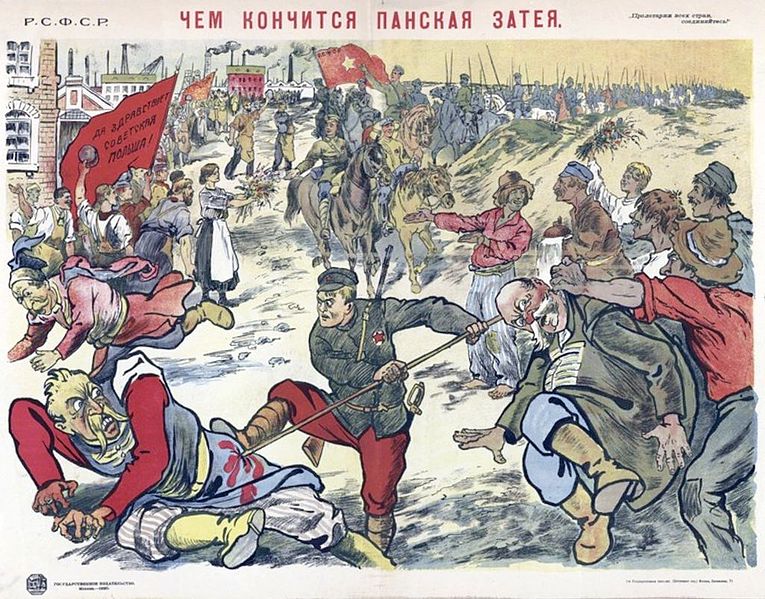

A Soviet propaganda poster of the Polish-Soviet War in 1920.

The war also empowered the General Staff in February 1917. With revolution taking hold in the capital of Petrograd, Tsar Nicholas II asked for the counsel of his generals and they encouraged him to abdicate. They knew that the war effort could only be revived without the tsar impeding their plans. The February Revolution then was in part a military coup.

The war also helped to radicalize the revolution over the course of 1917, paving the way for the Bolsheviks to seize power in October in the name of the Soviets. The Provisional Government that took power after the tsar abdicated never gave up on the war. It drew on popular nationalist sentiment and called on its citizens to give to the war effort as newly-free citizens of the Russian nation. They did, but especially after the disastrous June Offensive, more soldiers and workers at the homefront wanted an end to war, something the Bolsheviks called for.

A 1919 Russian White Forces poster depicting the Bolsheviks as a red dragon being defeated by a crusading knight representing the Whites (left). A 1916 tsarist poster entitled "Freedom Loan" entreating Russians to take out loans to fund World War I (right).

After seizing power in October 1917, the Bolsheviks flirted with the idea of changing the imperialist war into a struggle for global revolution. But at the end of 1917, Lenin understood from reports from the front that the war effort was hopeless. Soldiers had abandoned their posts en masse. Lenin pushed through the humbling Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, saving the infant Soviet state from full defeat just as a more immediate threat was starting.

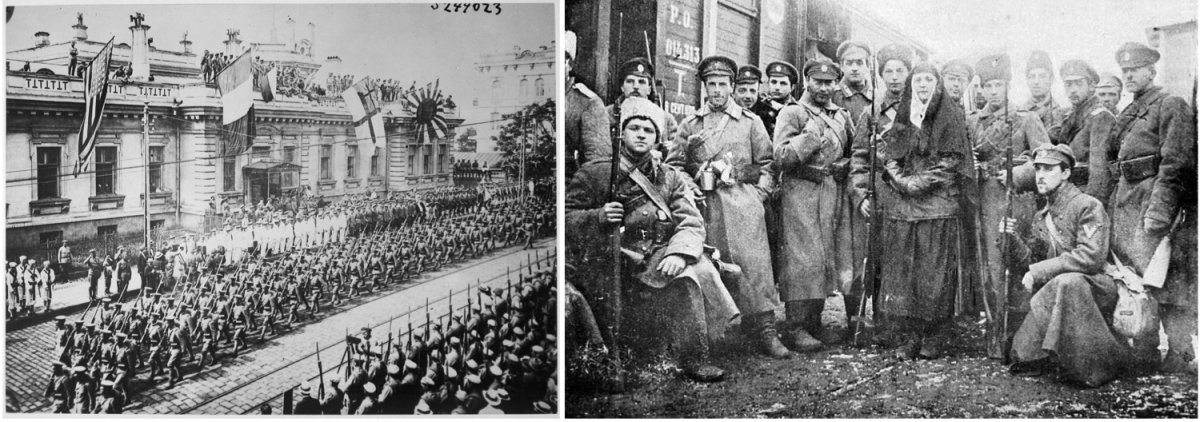

The Russian Civil War that followed the Bolshevik takeover of power—with its own waves of conscription and mobilization, disease, and famine—led to millions more deaths and social upheaval. Frontline soldiers went from fighting Germans to fighting fellow Russians. For most citizens of the former empire, wartime continued unabated from 1914 to 1922 and in Transcaucasia until 1926.

Soldiers from allied countries in Vladivostok, Russia during the Civil War in 1918 (left). Anti-Bolshevik Volunteer Army in South Russia in January 1918 (right).

State policies from the First World War also bled into the Civil War and created the foundation for the Soviet system. Soviet state practices during the Civil War often extended wartime policies adopted in 1914, such as conscription into the army, forced grain requisitions, surveillance of the population, official calls to arms, and the use of violence on civilians for military aims.

Almost by necessity, the new Soviet government during the Civil War created a centralized, bureaucratic state with a powerful army. In the 1930s, the Soviet state would use military images of storming barricades and staying on guard against invasion to mobilize citizens in its breakneck industrialization and forced collectivization of agriculture.

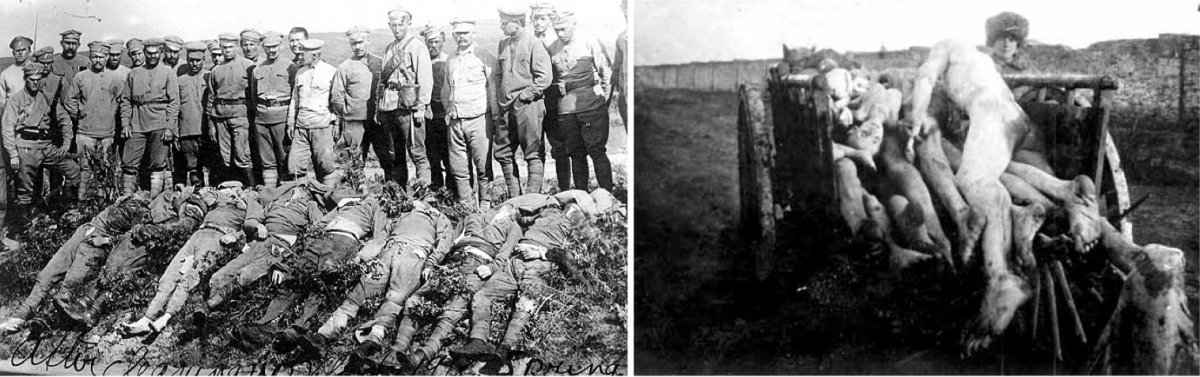

Czech legionaries killed by Bolsheviks at Nikolsk-Ussurlysky in 1918 (left). Russians who perished during the famine of 1921 (right).

The Soviet state, then, was defined by shared memories and state practices from the First World War.

Beyond transforming Russian society and creating the Soviet state, the war in Russia also reshaped global politics, which was no small feat.

The first Communist country in the world led to a red wave of revolutions across Europe as the war ended, two red scares in the United States, the Cold War, the spread of Communism in Asia and across the Global South, and inspiration for social movements as diverse as decolonization and neo-conservatism.

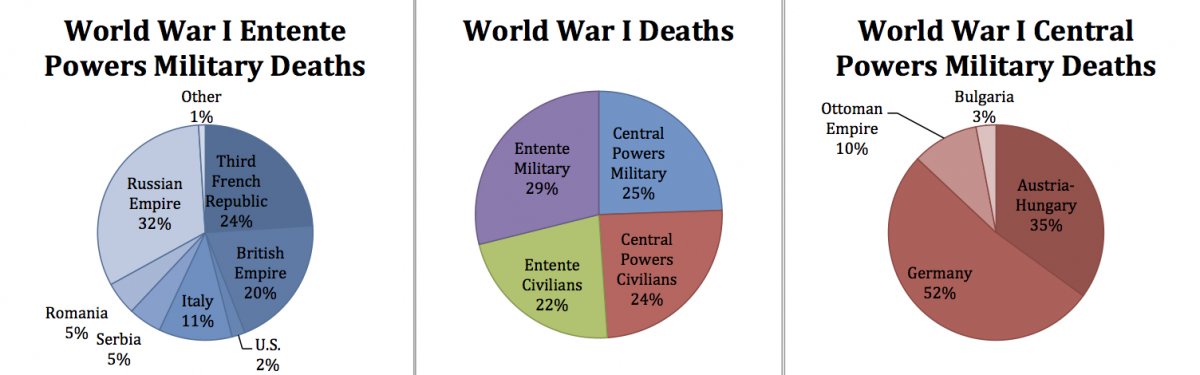

A pie chart of the military deaths of Entente Powers forces in World War I (left). A pie chart of military and civilian deaths in World War I (center). A pie chart of the military deaths of Central Powers forces in World War I (right).

The war’s most significant legacy was not just the toppling of the Russian imperial state, the first of the great empires to fall during the war. It was also not that Russia suffered the most casualties—roughly 3 million—of any combatant country. It was, rather, the revolution and its effect on state politics in what would become the Soviet Union and its reverberations across the world.

On August 1, 2014, to mark the centennial of the start of the First World War, Vladimir Putin opened a new memorial to “the heroes of the First World War”—Russia’s soldiers and officers. The statue sits at Poklonnaia Gora, alongside memorials to the Second World War and other Russian military conflicts.

Vladimir Putin at the 2014 opening of a new memorial to “the heroes of the First World War.”

Putin repeatedly emphasized in his speech that day that the statue was part of a national movement meant to bring back the long-forgotten history of soldiers of the war, to end the tragedy of forgetting, and to remind Russians of their sacrifices before victory was stolen from them.

Russia is rethinking the legacy of the war after the fall of the Soviet Union to put it in line with today’s strong Russian nationalism. The valor of the soldiers fighting in a tragic war for mother Russia has become the official legacy of the war. The war is finally being remembered in Russia. But this is a problematic history of the war, for it is one where the Revolution and the Soviet state that arose from it are hardly mentioned.

Read and Listen More on World War I: The Beginning of World War I and the Legacy of Gavrilo Princip; Memories of the Great War; Armenians, Turks, and the Genocide Question; On the Armenian Genocide; From Romanovs to Reds: Russia's Revolutions at 100; and the February Revolution and The October Revolution in Russia.

Check out a lesson plan based on this article: Legacies of WWI

Bruno Cabanes, August 1914: France, the Great War and a Month that Changed the World Forever (Yale University Press, 2016)

Thomas Laqueur, The Work of the Dead (Princeton University Press, 2015)

Jay Winter, Sites of Memory, Sites of Mourning: The Great War in European Cultural History (Cambridge University Press, 1995)

Jay Winter, War Beyond Words: Languages and Remembrance from the Great War to the Present (Cambridge University Press, 2017)

Stéphane Audoin-Rouzeau, Cinq Deuils de Guerre (Noésis, 2001)

Peter Gatrell, Russia’s First World War: A Social and Economic History. London: Pearson, 2005.

Peter Holquist, Making War, Forging Revolution: Russia’s Continuum of Crisis. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002.

Karen Petrone, The Great War in Russian Memory. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2011.

Joshua A. Sanborn, Imperial Apocalypse: The Great War and the Destruction of the Russian Empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Melissa K. Stockdale, Mobilizing the Russian Nation: Patriotism and Citizenship in the First World War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

Norman Stone, The Eastern Front, 1914-1917. New York: Penguin, 1998. First published in 1975.