On 20 November 1975, Spanish General Francisco Franco died in bed, signaling the unceremonious end of one of Europe’s longest dictatorships (1939-1975).

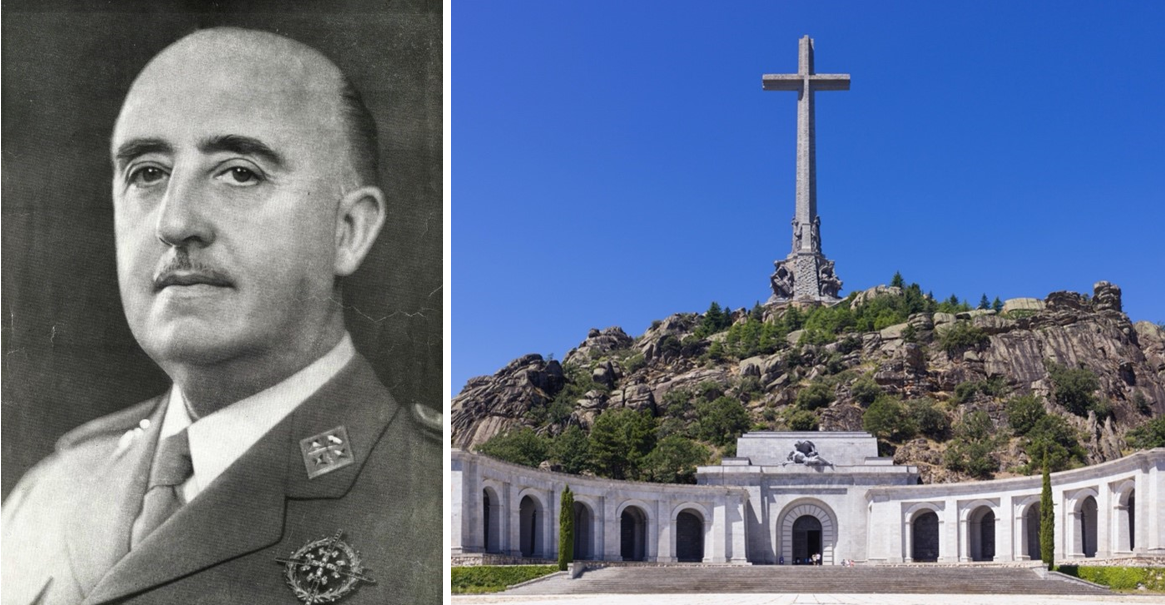

Portrait of Francisco Franco in 1964 from Biblioteca Virtual de Defensa (left). The Valley of the Fallen in San Lorenzo de El Escorial, Spain. (right).

On 24 October 2019, his remains were exhumed from the state-sponsored monument, Valley of the Fallen. Built by the Francoist regime during the 1940s and 1950s with the forced-labor of thousands of political prisoners, the Valley of the Fallen is a mass burial site that was designed to commemorate the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) as a “fratricidal conflict” and celebrate the triumph of “reconciliation.”

With the 2019 exhumation of the Caudillo (the Fascist-era title that Franco embraced as his own), the Spanish government retracted support from these timeworn narratives, paving the way toward a public reassessment of the legacies of Francoism.

The Spanish Civil War began on 18 July 1936 when General Franco and other Spanish officers from the colonial Army of Africa staged a failed right-wing military coup against the democratically elected Popular Front government.

Marina Ginestà at the top of Hotel Colón in Barcelona on July 21, 1936.

In response to the attempted coup, loyalist forces and popular militias rose up to defend the besieged republic. In turn, Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy came to the aid of the belligerent officers, airlifting the Army of Africa from the Spanish protectorate in Morocco to mainland Spain.

Like other interwar crises across Europe, the three-year conflict that ensued pitted those who wanted to preserve the hierarchies of the pre-1914 order against those who embraced social and political change. More than an ideological struggle between fascism and anti-fascism then, Spain splintered during the war as competing visions of the era’s most pressing social questions, such as gender and religion, were brought to the fore.

During the war, Franco’s so-called Nationalist forces pursued a campaign of systematic extermination, with aerial bombing of civilian populations, as in the case of Guernica; attacks on evacuees, as in the case of the Málaga-Almería Road Massacre; and the summary execution of teachers, intellectuals, and political opponents. By the war’s end, 350,000 Spaniards had died as a result of the conflict and another 500,000 had fled into exile.

The ruins of Guernica following the bombing in 1937.

In many ways, the dictatorship that ensued was initially just as brutal. Between 1940 and 1942, 200,000 Spaniards died because of political repression, hunger, and disease. Even Spaniards living in exile continued to suffer at the hands of the Caudillo. For example, during the Second World War, Francoist officials sent 10,000 Spanish prisoners of war in occupied France to Nazi concentration camps in Austria.

During the 36-year dictatorship, the Francoist regime never abandoned its signature political violence. However, brutality gave way to reform beginning in the 1950s. With the goal of establishing a strategic position in the emerging Cold War order, the regime touted its anti-Communist credentials, liberalized the economy, and introduced limited social and political reforms.

At the same time, three million Spaniards migrated from the rural south to the industrial north, where they broke the repressive bonds of postwar life and forged new relationships in cities and factories.

Taken together, these reforms from above and social changes from below laid the foundations for the Spanish “economic miracle” (1959-1974) and subsequent political transition in the wake of Franco’s death (1975-1982).

Members of the former regime and its opposition negotiated the political transition that followed under the supervision of King Juan Carlos, whom the dictator had selected as his personal successor. Working together behind closed doors, these transitional elites established a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary system based on the principles of representative democracy.

Once hailed as a model, the Spanish transition has come under scrutiny in recent years as new economic and political crises have emerged amidst growing demands for the recovery of historical memory.

Critics have called for the renegotiation of foundational pacts like the 1977 Amnesty Law, which released political prisoners in exchange for prohibiting legal proceedings against perpetrators of human rights violations. Although illegal under current international regulations, Spain’s Amnesty Law has remained in force, hindering criminal investigations and preventing the formation of Truth Commissions, as was common in other post-dictatorial societies such as Argentina, Chile, and South Africa.

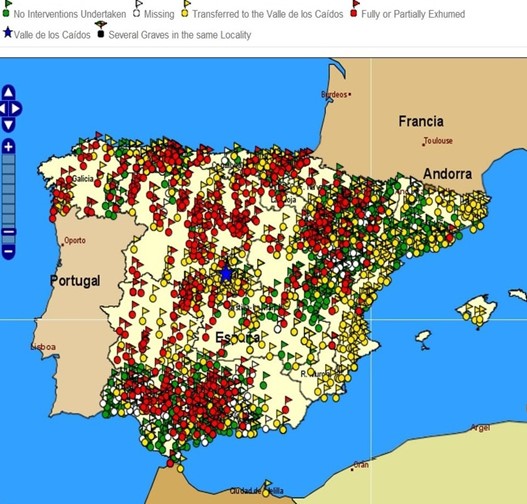

Spanish Civil War grave sites. Location of known burial places. Colors refer to the type of intervention that has been carried out. Green: No Interventions Undertaken so far. White: Missing grave. Yellow: Transferred to the Valle de los Caídos. Red: Fully or Partially Exhumed. Blue star: Valley of the Fallen. Ministerio de Justicia de España.

To date, the 2019 exhumation marks the state’s most definitive condemnation of Francoism. The Democratic Memory Act of 2020, which builds on the 2007 Law of Historical Memory and years of grassroots organizing, proposes to institutionalize this condemnation by converting the Valley of the Fallen into a civilian cemetery, preventing publicly-funded institutions from glorifying the dictatorship, and organizing the exhumation and identification of the estimated 112,000 victims of Francoism that are still buried in unmarked mass graves.