In the wake of the global financial collapse, the United States and other countries around the world have experienced historically low rates of inflation. Not so in Argentina. Although among the most advanced economies in Latin America, Argentina has been plagued for much of its history by sometimes unimaginable rates of inflation. This month historian Carlos S. Dimas reviews the history of South America's third most populous country to ask why Argentina cannot seem to escape from the curse of inflationary cycles and their social dislocations.

Read and Listen to Origins for more on Latin America: Cuba and the United States Reengage; Rethinking Cuba Libre; Global Migration and the Americas; Latin American Drug Trafficking; Brazil’s Elections;Brazilian Politics; and Anti-Americanism in Latin America.

Inflation has long been the great scourge of Argentina and its people.

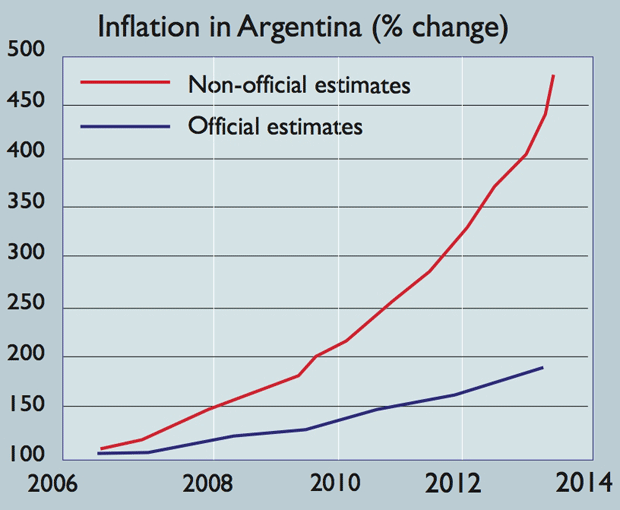

From 1944 to 2015, Argentina averaged a 204 percent inflation rate with a staggering record high of 20,263 percent in March 1990 and a low of -7 percent in February 1954 Officially, the inflation rate was recorded at 14.80 percent in July of 2015 (according to the INDEC, the national statistics institute).

And these official numbers may be on the low side.

There have been accusations in recent years that the government has been publishing false statistics. In 2012, The Economist magazine accused the government of “cooking the books” and reported that “since 2007, when Guillermo Moreno, the secretary of internal trade, was sent into the statistics institute, INDEC, to tell its staff that their figures had better not show inflation shooting up, prices and the official record have parted ways.”

Real inflation might be two to three times higher than the official record.

|

A few months ago, opposition legislators in Argentina decried the 15.6 percent officially stated inflation rate, asserting instead that Argentina was enduring a yearly rate of 41 percent, the highest rate since 1991, making it the second-highest inflation rate in South America next to Venezuela.

“Everyone is already suffering from higher costs for food, rents, and services,” said Deputy Patricia Bullrich. The government’s “deception has inflicted serious damage on our people,” added Deputy Carlos Brown. “It’s brutal, because people are forced to manage with an unreal situation. The discrepancy between reality and the official lie is more egregious each time.”

This discrepancy is readily apparent in the efforts of travelers and locals to convert currency. In the heart of Buenos Aires’ downtown at the intersection of the avenues of Florída and Lavalle, sits the center of an underground financial district where tourists and porteños (inhabitants of Buenos Aires) come to exchange currency.

As one walks the streets, the occasional calls of “Cambio, Dólar, Euro!” identify those willing to exchange currency. Armed with a cell phone and a calculator, the broker will provide the daily exchange rate of what Argentineans call the Dólar Blue (DB). Directly competing with banks and exchange houses, the brokers offer prime exchange rates with the hope of getting access to U.S. dollars.

The result is a rainbow currency market: Green Dollars are exchanged at the Blue Rate on the Black Market.

The deep social impact of inflation on the Argentinian people, publicized by the oppositionists, is nothing new. But it grew markedly in the wake of the great economic collapse of 2001.

|

| Police intervention in the 2001 riots |

In 2002, Norma Cecilia Albino walked into a bank in Buenos Aires and requested a cash withdrawal in U.S. dollars. Following the shattering economic crisis of 2001, this formerly mundane bank transaction was anything but. Her request was denied because it exceeded the daily quota for withdrawals. In an act of desperation she doused herself with gasoline and set herself ablaze.

Money-induced self-immolation has not been common in Argentina, of course, but this extreme event is a powerful symbol of the social costs and traumas of Argentina’s long struggle with inflation.

Why, we should ask, has Argentina so long and so regularly wrestled with this demon?

The question is especially important in a nation that in the late 1800s looked poised to become a global economic powerhouse. Argentina possessed railroads, agricultural commodities, bustling urban centers, and a bourgeoning middle class. Argentine newspapers such as La Ilustración Argentina reported on “the high life” and commented continually on the nation’s optimistic future.

|

| A protest against the banks and Corralito in 2002. The large sign reads "Thieving banks - give back our dollars." |

Yet a look back into Argentina’s economic and social history reveals over-reliance on its agricultural economy, trade deficits, limited economic planning and industrial diversification, and heavy dependence on foreign capital—even during periods of prosperity—which help us to understand the tendency to inflation.

In the modern period, overstretched international credit and a public distrust towards banks has stymied the economy. The past 30 years have been especially difficult.

Inflation remains part of the nation’s collective memory and is debated between the public, the government, and independent economic institutions such as the IMF.

In many ways, the aftermath of 2001 and the economic problems Argentina is facing today are part of a long string of booms and busts beginning in the 19th century.

The Roots of the Crisis

Throughout the colonial period (from the early 16th to the early 19th century), Rio de la Plata (modern-day Argentina, Uruguay, and Paraguay) was the backwater of the Spanish Empire. Due to the Empire’s closed mercantilist economy, exports and imports were only permitted through Peru and Mexico. Goods destined for Argentina tripled in price compared to elsewhere in Spanish America.

|

| Map of the La Plata Basin, showing the Río de la Plata at the mouths of the Paraná and Uruguay rivers, near Buenos Aires. |

Nevertheless, Buenos Aires thrived on pirated trade with English, French, and Portuguese sailors. In the 1770s, Buenos Aires finally opened officially for trade and the city became the capital of the new Viceroyalty of Rio de la Plata.

Following independence (beginning in 1816), Argentina’s leaders advanced liberal economic policies—free trade, foreign investment, export-oriented economies, and open borders—to spur local development and attract capital to the region.

|

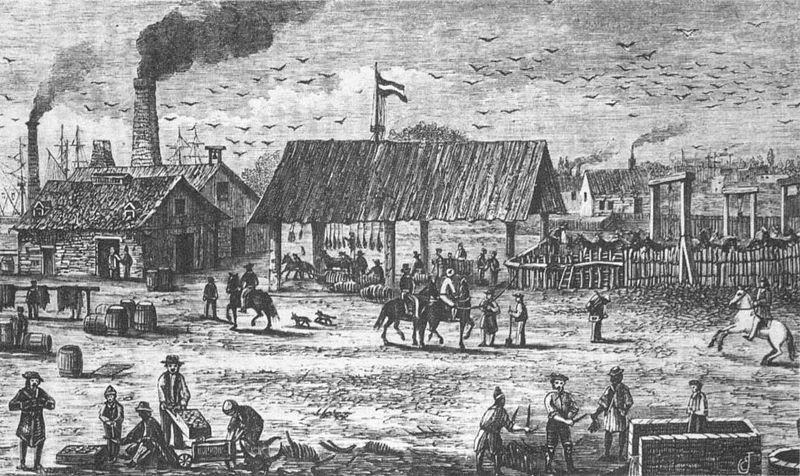

| A saladero (salted meat factory) at the Port of Rosario, 1865 |

England, especially, looked to Argentina to provide wheat, wool, and meat for the growing British industrial sector. From the 1800s to the 1940s, England and Argentina had a close economic bond through trade and loans that has shaped Argentina to this day. For example, British capital, labor, and supplies built most of Argentina’s railroads.

|

| Francis Baring (left), with brother John Baring and son-in-law Charles Wall, 1800. |

Bernardino Rivadavia, who served from 1826 to 1827 as the nation’s first president, acquired a one million pound loan from the Baring Brothers Bank, though financial misdealings meant that the government only received half that amount. It was the first in a series of private and public British loans to fund Argentine industries and the government.

|

| Bernardino Rivadavia, while he was in London, 1820s. |

During the dictatorship of Juan Manuel Rosas (1835-1852), Buenos Aires established the land-ownership patterns that consolidated large swaths of land into the hand of the estancieros (cattle owners) who exported their salted beef to feed both African slaves in the sugar fields of Brazil and Cuba and laborers in the English industrial sector. Under Rosas, the British cemented their economic influence in the region.

In order to maintain a viable relationship with British banks and entrepreneurs, the government devalued the local currency and lowered tariffs. British goods flooded local markets to the detriment of Argentine artisans, even while cattle owners benefited from exclusive trade with England.

Growth in the economy through trade did not translate into broader, more sustainable economic development.

To balance the books in the face of inflation and devaluation, Rosas slashed public subsidies and public works. A proponent of small government, Rosas fashioned the state into an acquirer of land on the Argentine frontier, which was then sold at low prices to large-scale farmers. This pattern continued following Rosas’ ouster.

There were underlying problems with this economy, despite the indices of overall growth. During the 1860s and 1870s, the nation continually battled against an ever-increasing trade deficit and its inability to decrease government expenditures, foreign debt, and inflation.

In 1876, Argentina defaulted on its loans for the second time, but British banks increased Argentina’s credit with the caveat that the government increase exports and further facilitate British investments in the region.

In the 1880s, Argentina recovered from the default in spectacular fashion under the Partido Autonomista Nacional (PAN, 1880-1916), a conservative political movement run by oligarchs.

|

| Buenos Aires Docks, 1915 |

During the decade, Argentina added miles of rail that further connected interior markets and goods to the ocean, the ports of Buenos Aires and Rosario were widened, new industries emerged (chilled beef, sugar, wool, tallow, wheat, fruit, and teas), and an agricultural organization of the interior dramatically improved the nation.

Through the PAN’s often coercive application of social order and economic progress, Argentina soon rivaled fellow emerging regions: the United States, Canada, and Australia.

Underneath the surface, however, the Argentine system looked much more suspect, with a weak banking sector, an absence of economic diversification, and artificial inflation.

During the governments of Julio Roca (1880-1886) and Miguel Juárez Celman (1886-1890) the majority of state-owned ventures were sold off to British banks. The national bank also switched the national currency from the gold standard, linking it instead to U.S. and British banking firms like the Baring Brothers Bank and the Rothschild Family.

|

| Julio Argentino Roca, 1900. |

First, the gold in the Reserve was earmarked for foreign companies such as the railroads. Under the railroad guarantee system, British companies were assured a certain rate of return on investment (ROI). If the amount was not met, the national government paid the remaining sum in gold, and not the devalued Argentine Peso. Local companies, however, were forced to do business in devalued currency.A devalued currency or “healthy inflation” can be beneficial because it can minimize risk for foreign investors and, in turn, attract capital. Yet in Argentina this practice created several long-term problems.

This method of national banking proved an absolute failure since most hard currency left Argentina. The nation’s debt increased and in 1888 the government requested an extension of credit from British banks.

The end came in 1890. Argentina defaulted on its loans for Buenos Aires’s public water system with the Baring Brothers Bank. The hit was felt harder in London. The bank was unable to acquire sufficient underwriters to stay afloat and Argentina single-handedly brought down the Baring Brothers.

In Argentina, unemployment and hyper-inflation were almost immediate. Following a popular uprising orchestrated by opponents and fellow PAN-members, Juárez Celman was forced to resign office.

|

| Miguel Juárez Celman, c. 1890s. |

In addition to these financial problems, the country was hurt by a failure to diversify its economy. Gifted with fertile pastures and wide open spaces, fortunes were made in exporting chilled beef, corn, wheat, and other vegetables. Yet combined with crises of overproduction, precarious global prices, foreign competition, and poor infrastructure, agriculturalists often reacted to lean years by investing even more in monoculture.

The northwestern province of Tucumán, which has a long history of producing sugar, provides a case in point. In the mid-1800s, local elites took the first steps in revamping local sugar mills with steam machinery acquired from Europe. Through a combination of national and private loans—routinely at a high interest rate due to limited banking options in the northwest and the abundance of sugar production in Latin America—the consortium of investors succeeded in taking the first steps in increasing production of refined sugar to meet local demand.

With the arrival of the railroad in 1876, sugar cultivation increased as mills began to tower over land solely dedicated to sugar. From 1876 to 1895, sugar quality and quantity grew at a rapid rate, while the province slowly eliminated alternative crops that had once grown abundantly: corn, wheat, and general produce. In order to assist local producers in dominating the national market, provincial representatives in Congress pushed through protectionist policies to close off the nation from cheaper Cuban and Brazilian sugar.

In 1895, Tucumán endured its first crisis of overproduction. In response, the province pushed for higher tariffs and increased production. Unable and unwilling to diversify, sugar growers produced more refined sugar in the hopes of inciting demand. Yet, the demand did not increase and a number of mills closed.

Sugar was not the only commodity to follow this path.

|

| Field of beef cattle in Argentina. |

For example, in the 1930s, Argentine beef exports to Great Britain were under competition from ranchers within the British Empire. Australian and South African beef exporters had succeeded in pushing British importers to place quotas on Argentine meat entering British homes. In order to guarantee the beef trade, the Argentine government signed the Roca-Runciman Treaty, which effectively lowered tariffs on goods entering Argentina.

Efforts to Break the Pattern

Beginning as early as the 1920s, an increasingly vocal group of national politicians called for an end to the nation’s reliance on foreign economic powers.

|

| A traffic jam caused by demonstrations prior to the 1937 presidential elections, Buenos Aires |

From the 1940s to the current period, various administrations have pressed for small goods—toasters, clothes, radios, and the like—to be manufactured domestically in order to increase local employment, expand the industrial sector, and boost consumerism.

Under the presidency of the populist Gen. Juan Domingo Perón (1946-1955), Argentina began to slowly break away from its dominant economic relationship with foreign powers, towards a more amicable one.

|

| Juan Domingo Perón, 1946. |

As part of Perón’s economic nationalist program (the Five-Year Plan) the government assisted manufacturing industries both in Buenos Aires and the interior. Flour mills, sugar mills, distilleries, and small industrial producers received large subsidies. In Córdoba, a metallurgy industry flourished under the joint efforts of local businessmen and the state. A Peugeot factory was built there.

Consumer confidence grew and imports decreased. From 1943 to 1955, living standards in Argentina improved to such an extent that they were comparable to Western Europe. The increase in union jobs fostered the development of a robust middle class that regularly consumed locally produced goods.

Yet Perón created numerous enemies in the upper class, among Catholics, and even within the labor movement since many of the industrial investments floundered due to mismanagement. Following his removal from power in 1955, he was exiled in Spain until 1973 when returned to Argentina.

His almost 20-year absence from power had resulted in the fragmentation of his support between right and left coalitions. A year later, Perón died and his wife, Isabel Perón, became the new president, a political transition that only further fueled conflict. In the end, she was ousted from power and the military held control until 1983.

The military governments steered the economy back to pre-Perón days.

In order to counteract inflation and the struggling industrial sector, the governments relied on numerous loans. Conditions worsened as the government began union-busting under the pretext that unions were housing “subversives.” The government soon began capturing, torturing, and killing union leaders, workers, and a host of other people.

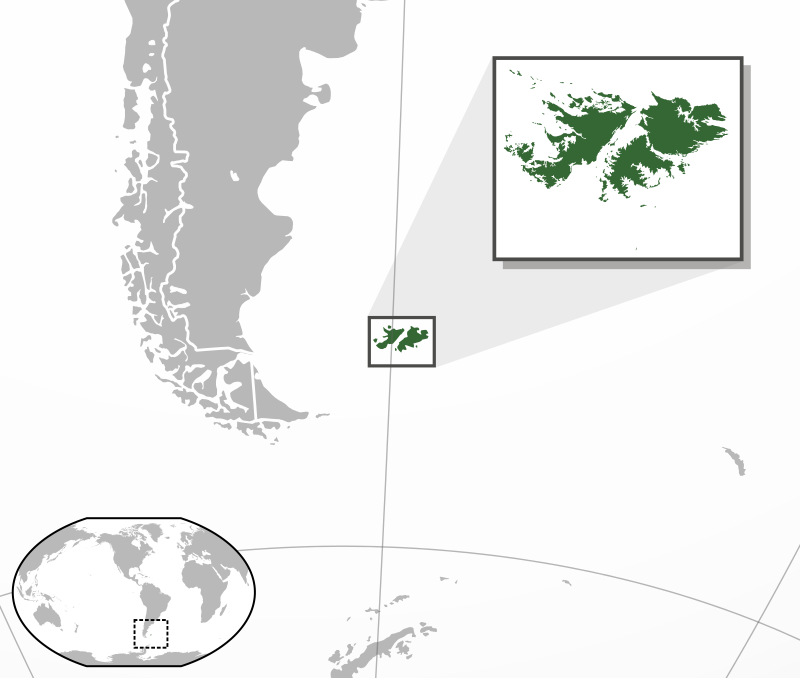

This attack on labor and its leaders drastically reduced industrial output. Social upheaval, a wrecked economy, and a devastating loss in the Islas Malvinas (Falkland Islands) war signaled the end for the military governments.

|

| Location of the Islas Malvinas / Falkland Islands |

The Crash and Crisis of 2001

In 1983 Argentina returned to democracy with the election of Raúl Alfonsín (1983-1989) from the Unión Cívica Radical party. Once the jubilation had subsided, Alfonsín was presented with the task of fixing a devastated economy plagued with an exorbitant foreign debt, rampant unemployment, and unparalleled inflation.

Two years into Alfonsín’s government not much had improved. Inflation hovered in the 1,000 percent range. Alfonsín looked to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for assistance.

In order to secure a loan, the IMF pressured Argentina to make significant reforms to stop inflation or face economic sanctions. As a quick fix to inflation, Alfonsín introduced the “Austral Plan,” a new currency to replace the longstanding peso in order to have a better control of how much paper money was in circulation.

The Austral failed disastrously. Limited bonds, shortening reserves, and increased unemployment inflated the new currency. Soon denominations of the currency jumped from 100 to 5,000 and closed off at 500,000. Prices on everyday items increased or decreased often in the span of hours.

At the close of Alfonsín’s presidency, newspapers were filled with stories of the price of a meal at restaurants changing from the moment it was ordered to the time the bill came.

|

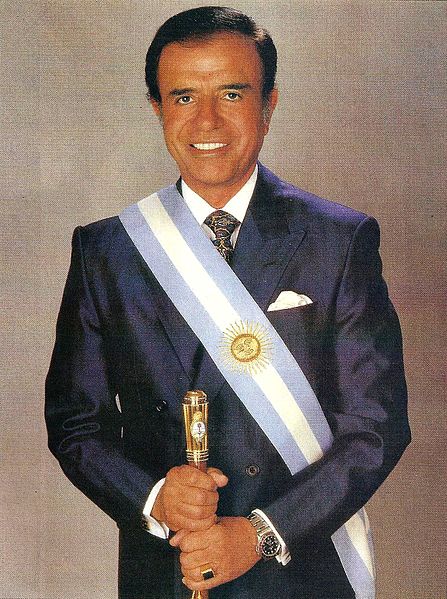

| Carlos Menem, c. 1990s. |

Hoping to repeat the success of Peronism, Argentines elected the Peronist candidate, Carlos Menem. Hailing from the western province of La Rioja, one of the nation’s poorest, Menem had successfully steered the province toward economic sustainability.

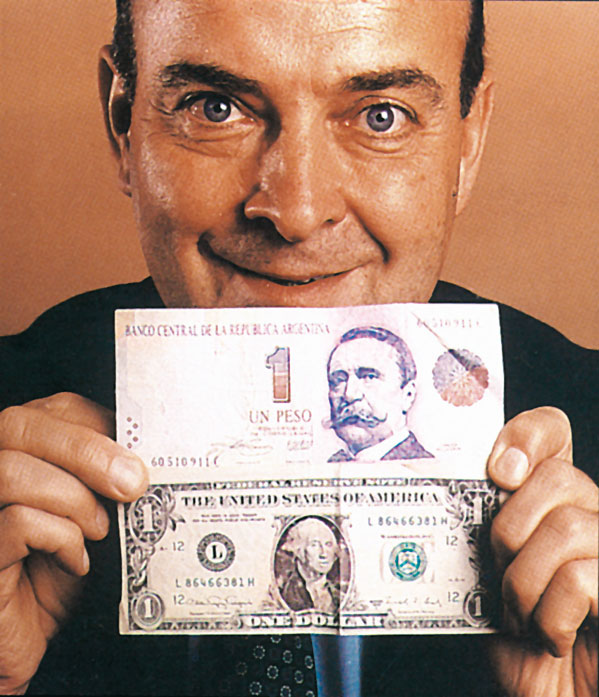

However, in a complete reversal of peronismo, once in office Menem pushed for the privatization of all major industries—in order to end government subsidies—and established the plan de convertibilidad, which tied the Argentine currency to the U.S. dollar—in the form of international credit from the IMF.

In 1991, the Argentine government established direct convertibility between the Argentine Peso (ARS) and the USD—a 1:1 exchange rate—as a tourniquet to high inflation and the depreciated local currency. The results were astonishing. Inflation dropped yearly and the USD was prized for its financial security.

Throughout the 1990s, IMF-Argentine relations reached their pinnacle. Pegged as an “emerging market,” the IMF extended the nation’s credit and brought in foreign bondholders to expand foreign reserves. In return, the IMF required the Argentine state to make various market-oriented structural changes: privatization, cuts in public spending, deregulation, the suspension or lowering of tariffs, and the opening of the nation to foreign companies.

During the 1990s, Argentina’s economy stabilized and grew at a steady rate of 6 percent per year. It came out almost unscathed from the “Tequila Crisis” of 1994 when the Mexican peso was devalued against the USD. At the social level, these reforms were also a success. Unemployment declined as foreign companies expanded their services. Flush with U.S. dollars, Argentines traveled, bought property, and boosted consumption.

Yet problems persisted that have affected the nation to this day.

First, for the remaining years of the 1990s, Argentines shifted their entire economy to the USD—economists estimated almost two-thirds of long-term financial contracts (mortgages, personal loans, and business loans) were in USD, thus requiring a healthy stream of currency.

Second, in order to maintain a healthy flow of USD into the Argentine Reserve, the government was forced to request loan after loan from the IMF. And the government was unable to complete many of the structural changes required by the IMF.

|

| Riots in December 2001 |

In December 2001, with an insurmountable foreign debt and uncontrolled national spending, the IMF cut off all further aid to Argentina. Foreign banks cleared out accounts in order to make up for the large loans.

The next morning Argentines woke up to find their bank accounts almost empty. People clamored to pull out the last few dollars that remained and many families lost everything.

To avoid a run on the banks, Domingo Cavallo, Minister of the Economy (above right), put forth the Corralito (corral) plan. The plan put strict daily quotas on the amount of dollars a person could withdraw. In between withdrawals, people such as Albino could only watch as their savings depreciated further.

Riots erupted and Buenos Aires’s financial district—a block from the presidential house—became the site of intense violence. Responding angrily to the quota, an HIV-positive person jabbed a bank teller with a needle filled with blood. In the outskirts of the city of Rosario, some families survived by hunting and eating feral cats.

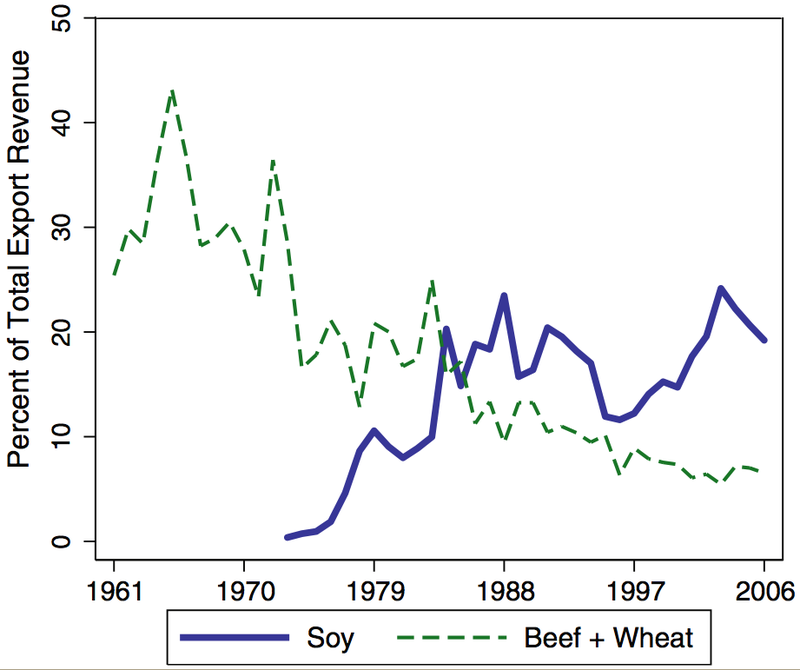

Argentina’s recovery from the crash of 2001 under the governments of President Néstor Carlos Kirchner (2003-2007) and Cristina Kirchner (2007-present) has been a long and arduous journey that has centered on reducing foreign debt, promoting local production of goods, and finding new markets for the agricultural sector (soy).

|

| In the mid-2000s, soybeans and soybean oil and meal generated more than 20% of Argentina's export revenue. |

The Kirchner period presents some of the inherent problems of its predecessors. In order to promote consumer confidence, the government outlawed the USD, which created a black market of foreign currency that is more representative of inflation, and prohibited the importation of goods that could be assembled in Argentina’s Tierra del Fuego. Yet their prices are high and rather than end demand for foreign products, it has actually created black markets for consumer goods. For example, Apple products, which are solely produced in Apple’s Chinese factories, are brought in from Miami and privately sold in the range of 20,000 pesos.

|

| Néstor Kirchner and Economy Minister Roberto Lavagna discuss policy, August 2004. |

Argentina Now and the Rush for the Dollar

Since the 2001 crash, the USD has become a coveted currency in Argentina for its financial security and resistance to inflation. Between 2001 and 2012, the government heavily regulated the amount of dollars citizens could purchase and under what circumstances. Yet, people soon began stockpiling private reserves, and in 2012 the government banned the USD. From this, the el blue conversion rate developed.

Although technically illegal, the blue has its benefits. Unlike the state-mandated rate, the unofficial exchange moves in conjunction with inflation and the rise in the cost of living. In 2014, for instance, when the DB peaked at 15.72 Argentine Peso (ARS), the official exchange rate was at 8.50 ARS.

This daily interaction has become so prominent that roughly $20 million is exchanged on the streets of Argentina per day. Newspapers publish the “official” exchange rate and el blue in their finance sections and the rate of the unofficial Blue Dollar can be followed on twitter, @DolarBlue.

Yet, the current government under Cristina Fernández de Kirchner has simply tried to ignore the el blue market and downplay its importance. According to the government, el blue is simply not an indicator of inflation and not an accurate exchange rate.

|

| National Bank of Argentina |

In 2013, Mercedes Marcó del Pont, former president of the Argentine Central Bank, publicly stated that the DB was “not relevant” in a discussion of the national inflation. Through a manipulation of the National Institute of Statistics and Census, the state deliberately publishes low inflation indexes to maintain political consent.

In order to counteract inflation and work around credit restrictions, Argentina has looked to China as a new creditor and market. Indeed, China has been more than willing to buy Argentine debt. In 2014 Argentina and China signed an agreement that will deposit 11 million yuan into the Argentine reserve by 2017.

|

| Presidents of Argentina and China (Cristina Fernandez and Hu Jintao) meet in Beijing, 2014. |

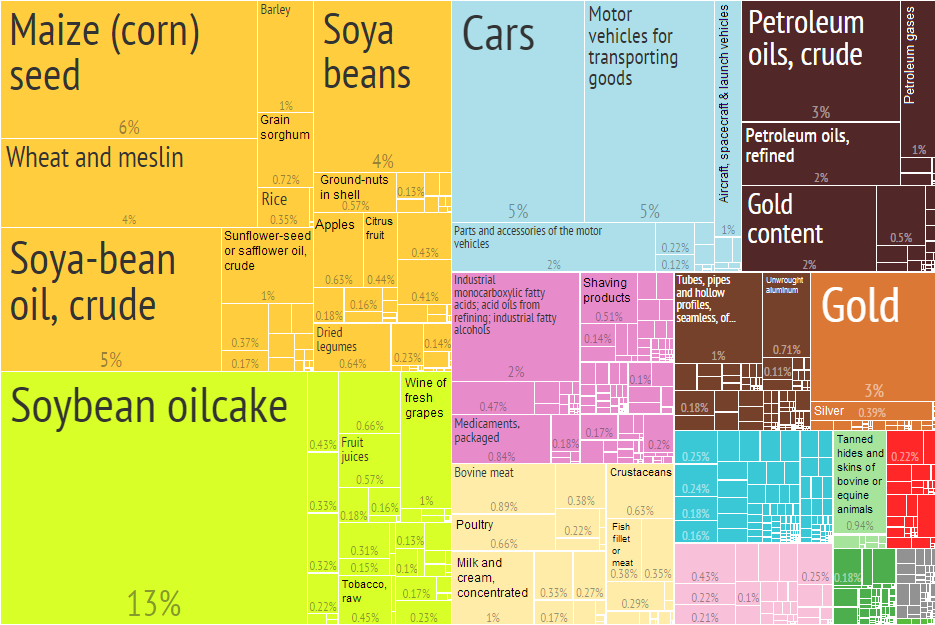

Most recently, Argentina and China have signed a trade agreement for $250 billion worth of investment in Argentina, and pledged to bring more Chinese families to Argentina. Chinese corporations will finance and build nuclear and hydroelectric plants and grain mills. In exchange, Argentina will provide soy, wheat, and beef to feed China’s growing urban sector.

No different than the nation’s reliance on the British sterling in the 19th century and the U.S. dollar in the 20th, Argentina’s financial future is tied to China’s.

Like the Argentina of the 19th century, modern Argentina has reverted to agriculture (GMO-soy and beef) as the foundation of its economy. As one of the world’s top producers of soy, Argentina’s global prominence is on the rise. Yet the social and environmental toll has been disastrous. Small- and medium-scale farmers cannot compete with large agricultural corporations, who employ an arsenal of pesticides with minimal regulatory oversight.

|

| 2012 Argentina Products Export Treemap |

The explosion of cancer and birth defects in the poorer provinces, such as Santiago del Estero and rural Córdoba, has begun to attract the attention of journalists and undermined the administration’s emphasis on human rights.

Argentina’s economic future is unclear. Perhaps in the coming months “Yuan!” will soon be added to the laundry list of currencies the Argentine black market will be willing to exchange for the local peso. Perhaps the economy will finally stabilize through soy exports. Perhaps things will stay just the way they are.

Brennan, James P., and Marcelo Rougier. The Politics of National Capitalism: Peronism and the Argentine Bourgeoisie, 1946-1976. University Park, Pa: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2009.

Blustein, Paul. And the Money Kept Rolling in (and Out): Wall Street, the IMF, and the Bankrupting of Argentina. New York: PublicAffairs, 2005.

Cortés Conde, Roberto. The Political Economy of Argentina in the Twentieth Century. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Della Paolera, Gerardo, and Alan M. Taylor. Straining at the Anchor The Argentine Currency Board and the Search for Macroeconomic Stability, 1880-1935. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001

Della Paolera, Gerardo, and Alan M. Taylor. A New Economic History of Argentina. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Pineda, Yovanna. Industrial Development in a Frontier Economy: The Industrialization of Argentina, 1890-1930. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 2009

Rocchi, Fernando. Chimneys in the Desert Industrialization in Argentina During the Export Boom Years, 1870-1930. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 2006.

Rochon, Louis-Philippe, and Matias Vernengo. Credit, Interest Rates, and the Open Economy: Essays on Horizontalism. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, 2001.

Romero, Luis Alberto. A History of Argentina in the Twentieth Century. University Park, Pa: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2002.

Sánchez Román, José Antonio. Taxation and Society in Twentieth-Century Argentina. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

Sitrin, Marina. Horizontalism: voices of popular power in Argentina. Edinburgh, Scotland: AK Press, 2006.