Cubans and Americans view their relationship very differently. Americans have long sought to insert themselves into Cuban affairs. For just as long, Cubans have insisted on defending self-determination and national sovereignty.

One of the last confrontations of the Cold War warmed considerably when American President Barack Obama and Cuban President Raúl Castro agreed to normalize relations between the two countries. Cuba and the United States have a shared history that stretches back well before the 1959 Cuban revolution and into the 19th century. As historian Louis A. Perez Jr. describes, however, what Cubans see when they look at that history is quite different from what Americans have seen. The lessons each nation has drawn from history will condition the future they shape together (or apart).

Read and Listen to Origins for more on Cuba and Latin America: Rethinking Cuba Libre; Global Migration and the Americas; Latin American Drug Trafficking; Brazil’s Elections; Brazilian Politics; and Anti-Americanism in Latin America.

At noon on December 17, 2014, Presidents Barack Obama and Raúl Castro announced to their respective nations that the United States and Cuba had agreed to resume full diplomatic relations.

The occasion was dense with history.

It could hardly have been otherwise, for it is impossible to assess what December 17 portends without understanding what preceded it. “There is a complicated history between the United States and Cuba,” President Obama acknowledged, and admitted too that “we can never erase the history between us.”

He affirmed the desire to leave “behind the legacy of colonization and communism,” concluding with the recognition that “change is hard,” especially “when we carry the heavy weight of history on our shoulders.”

In Havana, Castro also spoke of history. But while Obama hoped “to cut loose the shackles of the past,” President Castro summoned history not as rationale for change but as a reason for continuity.

|

|

| President of the United States, Barack Obama (left) and President of Cuba, Raúl Castro (right). | |

“The heroic Cuban people,” he affirmed, “in the wake of serious dangers, aggressions, adversities, and sacrifices has proven to be faithful and will continue to be faithful to our ideals of independence and social justice. Strongly united throughout these 56 years of Revolution, we have kept our unswerving loyalty to those who died in defense of our principles since the beginning of our independence war in 1868.”

Three days later, Castro told the Cuban National Assembly that “no one should expect Cuba to renounce the ideas for which it has struggled for more than a century, and for which its people have shed lots of blood and run the biggest risks in order to improve its relations with the United States,” and emphasized that it was “necessary to understand that Cuba is a sovereign State.”

Both countries have looked at the same history and seen something very different. The experience of the past 55 years serves to set in sharp relief their profoundly different lived histories during what the Wall Street Journal characterized as years of “long-strained relations.”

Americans have seen these years as a tenacious effort to free Cubans from a tyrannical government.

Cubans have seen the same events as half a century of sustained U.S. efforts at regime change, including armed invasion, economic sanctions, political isolation, scores of assassination plots against the Cuban leadership, and years of covert operations including the disruption of Cuban agriculture and the sabotage of its industry. Today, many of these efforts could be understood as acts of state-sponsored terrorism.

For more than 200 years, American leaders have found it difficult to reconcile themselves to the proposition of an independent and sovereign Cuba, as evidenced in 1898 during the Spanish-American War and in 1959 during the Cuban Revolution.

The destinies of both Cuba and the United States have been not merely intertwined, but indissoluble. Cuba loomed large in American collective self-awareness and in the calculus of national security. In turn, American attitudes, actions, and policies have shaped what independence and sovereignty mean for Cubans. Each country developed a sense of history that accommodated the presence of the other. Each country intruded upon the other at formative moments of national development.

Intertwined Destinies: The American Fixation with Cuba in the 19th century

Lying astride the principal sea lanes of the middle latitudes of the Western Hemisphere, commanding on one side entrance to the Gulf and outlet of the vast Mississippi Valley and, on the other, fronting the Caribbean Sea, Cuba assumed far-reaching strategic and commercial importance in the minds of 19 th- century Americans.

“An object of transcendent importance to the political and commercial interests of our Union,” John Adams pronounced in 1823. “It is scarcely possible to resist the conviction that the annexation of Cuba to our federal republic will be indispensable to the continuance and integrity of the Union itself.”

This became an enduring policy consensus for more than a century.

A sense of national completion seemed to depend on Cuba, without which the American Union seemed unfinished and vulnerable. “We must have Cuba. We can’t do without Cuba,” future president James Buchanan implored Secretary of State John Clayton in 1849.

In short order Americans persuaded themselves that the well-being of the entire world depended on U.S. possession of Cuba. As Senator James Bayard put it in the middle of the nineteenth century: “[T]he future interests not only of this country, but of civilization and of human progress, are deeply involved in the acquisition of Cuba by the United States.”

But Cuba also became deeply embedded in the moral systems around which Americans fashioned their founding myths and laid claim to U.S. exceptionalism. The acquisition of Cuba was not simply a matter of a pragmatic foreign policy but a fulfillment of Providential purpose.

“It is because Cuba has been placed by the Maker of all things in such a position on earth’s surface as to make its possession by the United States a geographical and political necessity,” insisted Representative James Clay at mid-century; “we must have Cuba, from a necessity which the Maker of the world has created.”

Representative Townsend Scudder echoed the sentiment, insisting that Cuba was a “territory that God and nature intended to be a part of the United States.” And the Ostend Manifesto (1854) proclaimed outright that Cuba “belongs naturally to that great family of states of which the Union is the providential nursery.”

Cuba: A Different Destiny

Cubans in the 19th century, however, also developed a vision of their destiny, but in very different terms. No other aspiration so profoundly shaped the formation of Cuban national sensibility as the idea of national sovereignty and self-determination from Spanish control.

Sugar had catapulted Cuba into the swell of global capitalism. The economy had previously languished within a system of eighteenth-century colonial mercantilism, but it began to expand in form and function around nineteenth-century market capitalism, with far-flung international trade linkages.

Cubans organized their economy around an emerging agro-industrial production system driven by the development of new technologies, new marketing strategies, new distribution networks, and new modes of transportation—and they became integrated into the world at large.

That they belonged in that world they never doubted. Cubans would be marked permanently by the experience: a people imbued with a sense of rightful claim for inclusion among the modern nations of the world at large, fully persuaded that they had a right to sovereign nationhood and claim to self-determination—to a Cuba for Cubans.

Throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, over the course of successive armed uprisings against Spanish colonial rule, Cubans mobilized in pursuit of a nation of their own. Independence would give them the power to articulate their identity and advance Cuban interests.

Therein lies the trajectory of the fateful relationship between the countries: the American resolve to possess Cuba and the Cuban determination to resist possession.

Therein lies the trajectory of the fateful relationship between the countries: the American resolve to possess Cuba and the Cuban determination to resist possession.

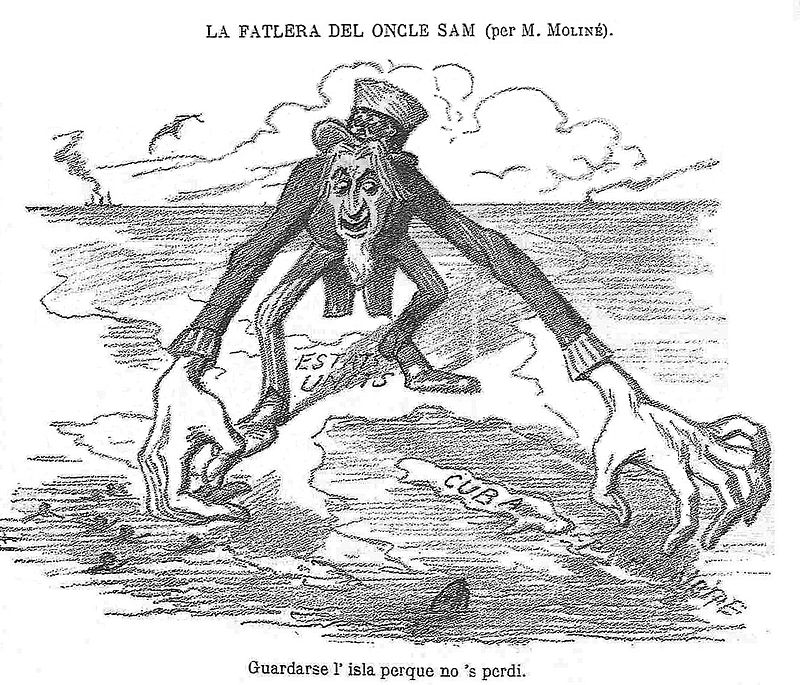

The specter of American expansion loomed large in the preparations for the war of independence in the late 19th century.

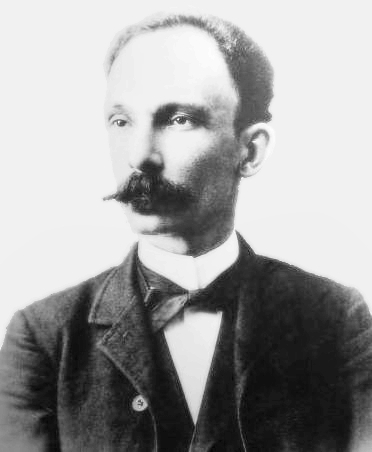

José Martí (left)—“Apostle of Cuban Independence”—planned for a war of independence against Spain ever mindful of U.S. intentions. All through the 1880s and 1890s he warned—prophetically—of the need for a well-organized and rapid war of independence. Otherwise, he worried, “it may be our fate to have a skillful neighbor let us bleed ourselves on this threshold until finally he can take whatever is left in his hostile, selfish, and irreverent hands … and with the credit won as a mediator and guarantor, keep [Cuba] for [his] own.”

The War of 1898 and a “Free” Cuba

1898 was the year of denouement, the point at which the history of both countries wrapped around each other in structural form with the much-anticipated succession of U.S. sovereignty over Cuba. Americans entered the war against Spain in the swoon of history, as if in discharge of prophetic purpose: the interests of the nation properly–and finally–aligned with Providential design. History had come to pass in 1898 as it was meant to. The Americans took up the war and took over the peace.

They had arrived in the guise of allies and remained in the role of conquerors. Certainly vast sectors of the American public supported the cause of Cuba Libre, but the William McKinley administration, its allies in Congress, and supporters in the press did not.

The American purpose was explained in 1902 by Governor General Leonard Wood, who pronounced that by ending Spanish sovereignty over the island, the United States “assumed a position as protector of the interests of Cuba. It became responsible for the welfare of the people, politically, mentally and morally.” Here was the transfer of sovereignty over Cuba—from Spain to the United States—just as the Americans had always imagined.

Cuba had been wrested from Spain—indeed, Cuba had been wrested from Cubans too. The Americans took over the Cuban war for independence and renamed it the “Spanish-American War,” a designation that served at the time and long thereafter to deny the presence and participation of Cubans as actors and agents.

The Americans did not start a war; they joined one in progress. They inserted themselves between weakened Spaniards and weary Cubans, to complete the defeat of the former and foreclose the victory of the latter, and thereupon advance claim of possession of the island as spoils of war.

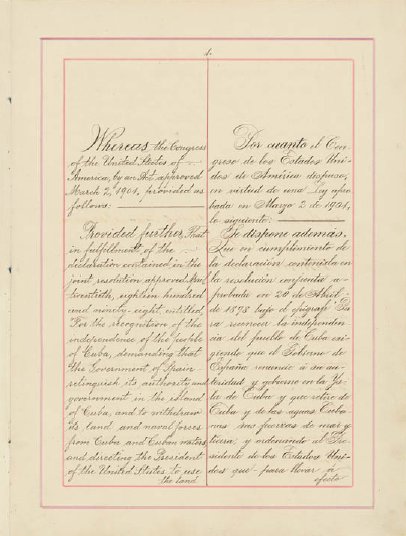

The U.S. military occupation (1899-1902) ended only after the Cubans acquiesced to the Platt Amendment, which was incorporated into the Cuban Constitution of 1901 and subsequently ratified as the Permanent Treaty (1903).

|

| The opening page of the 1901 Platt Amendment, a document that gave the U.S. significant power over Cuba. |

By this means, the Cuban republic was shorn of all essential properties of national sovereignty prior to its establishment, denied authority to enter into “any treaty or other compact with any foreign power or powers,” denied too the authority to contract a public debt beyond its normal ability to repay, and forced to cede national territory to accommodate a U.S. naval station in Guantánamo Bay.

Lastly, Cubans were required to concede to the United States “the right to intervene” for the “maintenance of a government adequate for the protection of life, property and individual liberty.”

The military occupation would not end, the Americans warned, until Cubans incorporated the Platt Amendment into their constitution, that is, until Cubans renounced their claim to national sovereignty as a condition of self-government.

It seemed as if Cuba had been overtaken by another country’s history. In a sense it had. The Cuban liberation project had been successful on every count except perhaps the one that mattered most: the attainment of national sovereignty and self-determination.

The Platt Amendment eviscerated all but the most cynical meaning of nationhood. Cubans had obtained independence without sovereignty, self-government without self-determination.

Cuban efforts at self-determination in the decades that followed were repeatedly thwarted. An armed uprising in 1906 against a U.S.-imposed government, for example, resulted in another U.S. intervention and occupation (1906-1909). Armed interventions occurred again in 1912 and 1917.

In the decades that followed, U.S. ambassadors inserted themselves deeply into Cuban internal affairs. These prying officials included Enoch Crowder, Sumner Welles, Spruille Braden, and Earl E. T. Smith, among others, all of whom assumed something of a proconsular bearing in Havana. “We have always to consider,” exhorted Crowder in 1922, “the eternal vigil that must be exercised by America’s representative in Cuba.”

The practice of “eternal vigil” defined the role and power of the U.S. embassy in Havana. “The United States,” former ambassador Earl E. T. Smith acknowledged in 1960, “until the advent of Castro, was so overwhelmingly influential in Cuba that . . . the American Ambassador was the second most important man in Cuba; sometimes even more important than the President.”

Nonetheless, Cuban aspirations for national sovereignty and self-determination persisted. The failure to redress the social and political grievances that had served to mobilize vast numbers of Cuban men and women to dramatic action in the nineteenth century had a decisive effect on the character of politics in the twentieth century. A sense of unfinished purpose and unrealized goals settled over the early republic.

Cubans were obliged to remember, insisted historian Ramiro Guerra y Sánchez in 1923, “the great deeds realized by our fathers in defense of our homes, our liberty, and our rights.” And he added: “The Cuban who comes to know the history of our past will feel heir to a rich patrimony and will discover in that very legacy the means to make it greater…. Our history is the only thing that we possess that is genuinely ours.”

Literary critic Jorge Mañach distilled the essence of Cuban angst: “Cuba has always been in fact a people debarred from self-determination,” he wrote in 1933. “The Cubans have not been able to shape their destiny according to their own will, because that will has been laid in semi-subjection.” The Platt Amendment, Mañach added, had “resulted in crushing the Cuban sentiment of self-determination, when it imposed express limits on the exercise of the collective will.”

Literary critic Jorge Mañach distilled the essence of Cuban angst: “Cuba has always been in fact a people debarred from self-determination,” he wrote in 1933. “The Cubans have not been able to shape their destiny according to their own will, because that will has been laid in semi-subjection.” The Platt Amendment, Mañach added, had “resulted in crushing the Cuban sentiment of self-determination, when it imposed express limits on the exercise of the collective will.”

A military coup led by General Fulgencio Batista (left) in 1952 plunged Cuba into political crisis and brought Cuban discontent into sharp focus. Batista came to represent all that was objectionable about the Cuban condition; he was both symbol and symptom of the failure of the republic, the corruption of public life, the venality of political leaders, the influence of America, and the futility of political institutions.

As Cuban men and women joined the armed resistance against Batista and American intervention during the 1950s, they drew inspiration and motivation from the past as they looked to a different future.

The Continuity of Castro’s Revolution

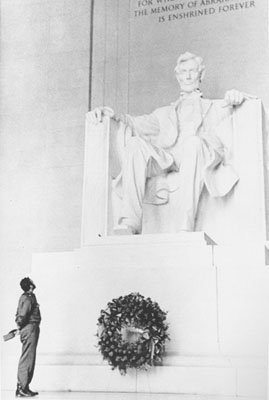

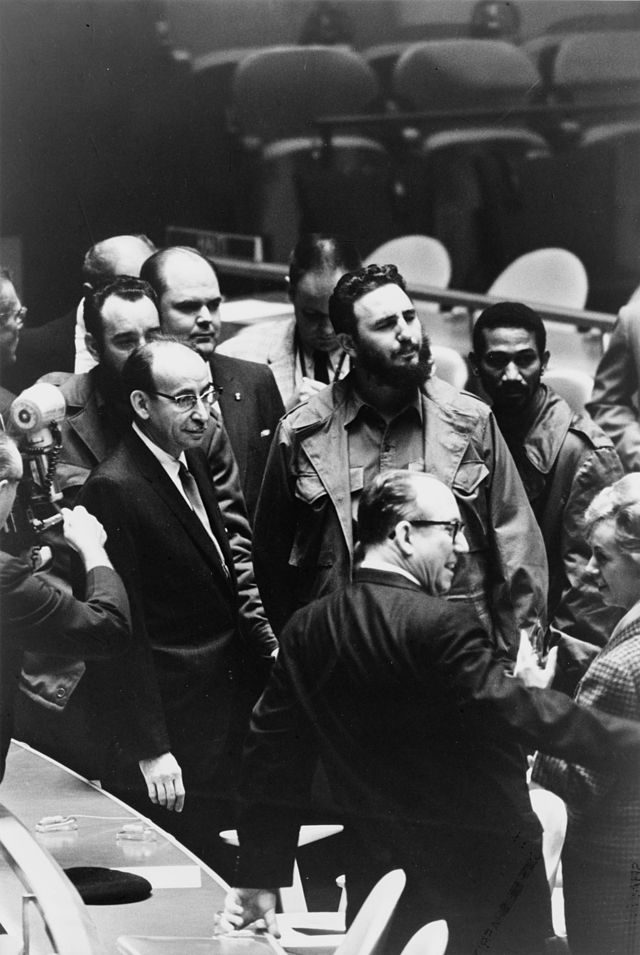

|

| Shortly after becoming Prime Minister of Cuba, Fidel Castro visits the Lincoln Memorial during a trip to the United States. |

The political forces that crashed upon one another in fateful climax in 1959 were thus set in motion long before the triumph of the Cuban revolution. Many Cubans heralded Fidel Castro’s revolution as the completion of the unfinished liberation project of the nineteenth century, which conferred moral authority on the revolution in the twentieth century.

Whatever else the Cuban revolution addressed, whatever other ills the revolution sought to remedy, at the core of its mystique was the idea of the Cuban nation imbued with the properties of national sovereignty and self-determination, the one condition Americans could not abide.

The enactment of national sovereignty began almost immediately with the introduction of far-reaching reforms to the economy and the structures of government. The new leadership took over the Cuban Telephone Company and the Cuban Electric Company, significantly reducing the rates of both. They increased minimum wages in agriculture, industry, and commerce. The Urban Reform Law decreed across-the-board reduction of rents. The Agrarian Reform Law nationalized properties exceeding 3,333 acres.

Reform policies affected U.S. interests directly. American imports declined. International Telephone and Telegraph protested the reduction of its rates. So did the Cuban Electric Company. American sugar companies protested the Agrarian Reform. U.S. employers protested increased minimum wages.

All through 1960, nationalization of U.S. properties, including oil refineries, proceeded apace. Washington protested, both publicly and privately, and responded politically and economically.

The United States cut the Cuban sugar quota, prohibited exports to Cuba except for foodstuffs, medicines, and medical supplies, and in January 1961 the United States suspended diplomatic relations. By the end of 1960, the U.S. government had developed a plan of covert operations to topple the Cuban government, including what would become the Bay of Pigs invasion.

|

| Fidel Castro attending the 1960 United Nations General Assembly. |

But the worst was yet to come.

The alarm with which the United States responded to Cuban domestic policies was eclipsed by the abhorrence with which it reacted to Cuban foreign policy, specifically expanding ties with the Soviet Union. Simply put: Americans were aghast. How utterly implausible: of all places—Cuba?

Never before—certainly never before in Latin America—had a duly constituted and recognized government mounted so strident an attack on the policies and practices of the United States.

“We have never in our national history,” a very chagrined Henry Ramsey of the State Department Policy Planning Staff commented in 1960, “experienced anything quite like it in magnitude of anti-US venom.” “Cuba’s move toward communism,” Secretary of State Dean Rusk later wrote, “had been a deep shock to the American people.”

In an interview in the 1990s, news broadcaster Walter Cronkite aptly conveyed something of the cognitive dissonance that jolted the breezy assumptions informing popular knowledge of Cuba.

“The rise of Fidel Castro . . . was a terrible shock to the American people. This brought communism practically to our shores . . . . We kind of considered [Cuba] part of the United States–of course, it is part of America—we considered it part of the United States practically, just a wonderful little country over there that was of no danger to anybody . . . . The country was a little colony. Suddenly, revolution, and it became communist and allied with the Soviet Union. … An ally of the Soviet Union, right off of our shores—it was frightening.”

Indeed, in a Cold-War culture shaped by paradigms of balance of power and spheres of influence, the presence of the Soviet Union at a distance of 90 miles wrought havoc on some of the most fundamental premises of U.S. strategic thinking, “imperiling the very survival of the United States,” despaired Ambassador Spruille Braden.

The rhetoric rang with apocalyptic forebodings. Congressman Mendel Rivers warned of “the agonies of Communist cancer, which most assuredly will engulf the Nation if Cuba is allowed to fester as the cell from which this cancerous growth will spread.” Central Intelligence Agency Director John McCone was somber: “In my opinion, Cuba was the key to all of Latin America; if Cuba succeeds, we can expect most of Latin America to fall.”

Yet, in the midst of this shock and crisis, the United States had responded predictably. Cuba was not the first Latin America country to challenge U.S. interests. Only five years earlier Guatemala had undertaken an agrarian reform project that involved the nationalization of U.S.-owned property—and was promptly overthrown by a CIA covert operation. Indeed, the U.S. covert operations against Cuba were modeled on those used against Guatemala.

But if the U.S. responded in predictable fashion, Cuba did not. History had prepared Cubans for American reactions but there was nothing to prepare the United States for the Cuban response. In this sense, the Cubans had the advantage.

The Cubans replied to U.S. pressure with the previously unthinkable: the expansion of trade and commercial relations with the Soviet Union. Once assured of a market for its exports, the Cuban government moved aggressively to eliminate the U.S. presence on the island—in the name of national sovereignty and self-determination.

All through the years that followed the revolution, the Cuba-U.S. confrontation deepened and widened. The two nations—each in its own way imbued with a powerful sense of exceptionalism— became locked in continual reenactment of their history: the Cubans insisting on the exercise of national sovereignty, the Americans demanding deference to U.S. national interests.

U.S. efforts at political pressure, diplomatic isolation, economic sanctions, and years of covert activities failed to curb Cuban policies. On the contrary, it produced the opposite effect, and served further to deepen the estrangement. Cubans expanded moral and material support of guerrilla movements in Latin America and participated in liberation movements in Africa.

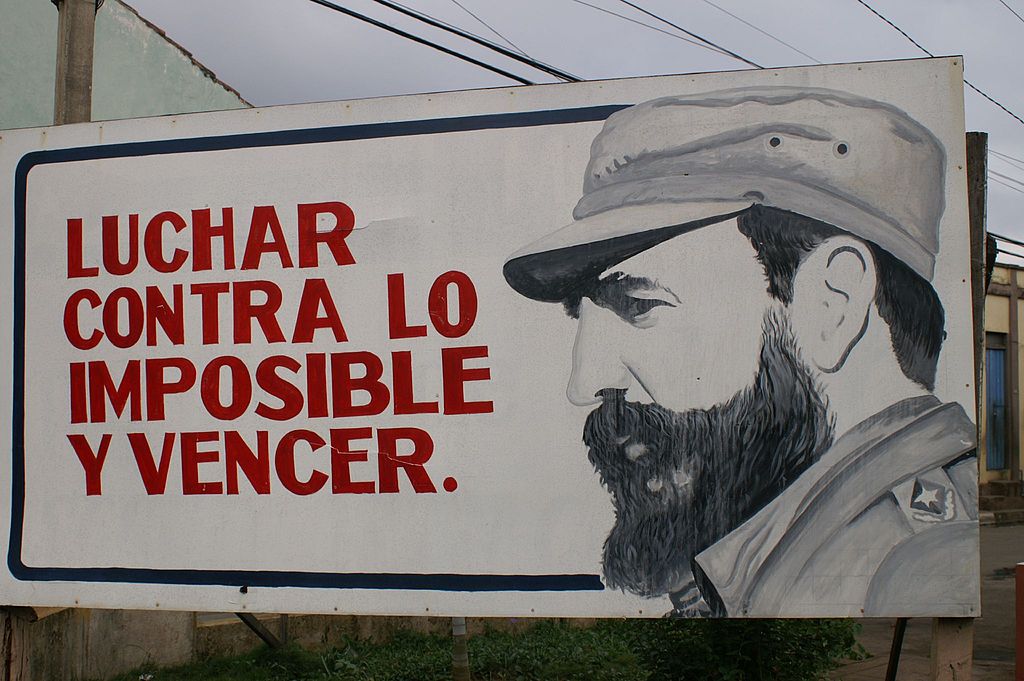

|

| This Cuban propaganda sign features the profile of Fidel Castro and when translated reads "Fight against the impossible and win." |

What appeared to U.S. eyes as Cuban intransigence was, in part, a manifestation of the Cuban refusal to submit to the United States, borne by a people fully persuaded that they had a right of national sovereignty. Rather than weakening national resolve in Cuba, sanctions strengthened Cuban determination. U.S. policy served to bring out some of the most stubborn tendencies of the Cuban leadership in the defense of exalted Cuban claims to national sovereignty.

The ferocity of the Cuban defense of national independence spanned multiple generations across a century, from the nineteenth-century wars of liberation to the defense of the revolution. Little separated the sentiment of independence leader Manuel Sanguily from Fidel Castro:

Sanguily (1875): “We have one unshakeable purpose: to fight [for independence], to fight without rest, to fight without pause, . . . to fight until there are no more Cubans capable of clutching a rifle or until the last Cuban is buried under the rubble of the fires set by our indignation and ire . . . . We accept everything, we have accepted everything, we will [continue] to accept everything–death in battle, death on the gallows, death due to hunger and disease, exile, prison, assassination, ruin of our wealth, the devastation of our land–all the misery, all the torment.”

Castro (1980): “They threatened us with an economic blockade? Let them maintain it for one hundred years if they wish! We are disposed to resist for one hundred years . . . If we have to disperse across the entire country . . . to cultivate the land with oxen and plows and with hoes and picks in order to live, we will but we would continue to resist. If they believe that we will surrender because we lack electricity, or bus service, or oil, or whatever, they will see than they can never bring us to our knees and that we are capable of resisting for one year, for ten years, for as many years as necessary, even if we have to live like the Indians that Columbus found when he arrived to Cuba 500 years ago.”

A New Era Built on Old Assumptions?

The past weighs heavily on the present diplomatic negotiations between Havana and Washington. Both Cubans and Americans are deeply entangled in the complex logic of their own history. Both countries have indeed been handcuffed by past decisions: the Cubans with a system that has foundered, the Americans with a policy that has failed.

For more than half a century, the United States used punitive sanctions to remove a government that defied the presumption of U.S. power over a country long believed to be “territory that God and nature intended to be a part of the United States.”

The intent was to politicize hunger as a means to foment popular disaffection, in the hope desperate Cubans would rise up and overthrow their government.

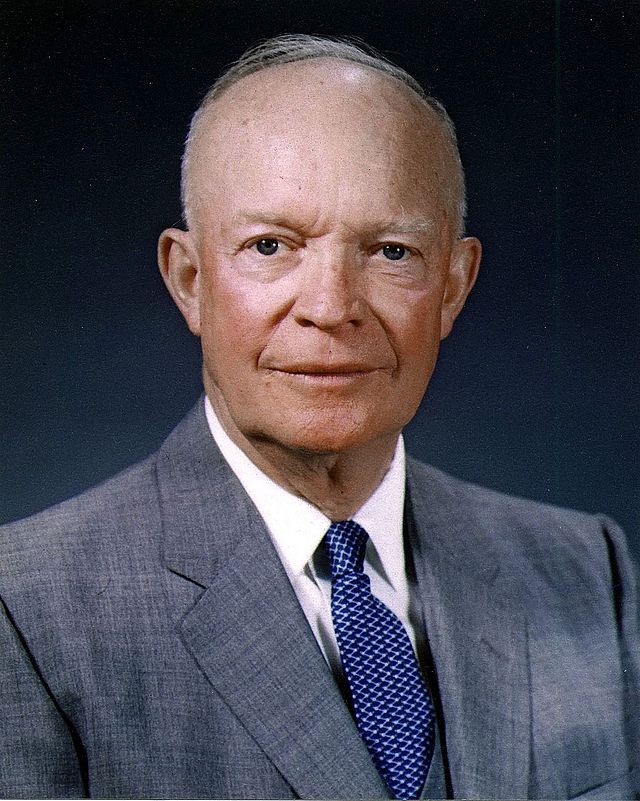

President Dwight Eisenhower (right) ordered economic sanctions against Cuba, reasoning that “if [the Cuban people] are hungry, they will throw Castro out.” The President’s approach developed into the basis of the policy rationale for 50 years.

President Dwight Eisenhower (right) ordered economic sanctions against Cuba, reasoning that “if [the Cuban people] are hungry, they will throw Castro out.” The President’s approach developed into the basis of the policy rationale for 50 years.

“The only foreseeable means of alienating internal support,” concluded Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs Lester Mallory as early as 1960, “is through disenchantment and disaffection based on economic dissatisfaction and hardship.” Mallory recommended that “every possible means should be undertaken promptly to weaken the economic life of Cuba” as a means “to bring about hunger, desperation and [the] overthrow of the government.”

Punitive sanctions were expanded after the collapse of the Soviet Union, in 1992 (the Cuban Democracy Act, sponsored by U.S. Congressman Robert Torricelli) and 1996 (the Helms-Burton Act), and tightened again during the administration of George W. Bush.

By this time, almost 20 years into the post-Cold War era, the matter of Cuba had become a peculiar American obsession. The Cuban leadership would not be forgiven for having made the United States vulnerable, represented most vividly by the installation of Soviet missiles in 1962 during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Condoleezza Rice recalled her childhood during the missile crisis, and remembered that it was the first time she experienced “feeling truly vulnerable.” Fidel Castro had “put the U.S. at risk in allowing those missiles to be deployed,” and to the point: “He should pay for it until he dies.”

When asked under what conditions the United States would consider normalization of relations with Cuba, President Ronald Reagan responded: “What it would take is Fidel Castro, recognizing that he made the wrong choice quite a while ago, and that he sincerely and honestly wants to rejoin the family of American nations and become a part of the Western Hemisphere.”

Roz Chast titled her 1995 New Yorker cartoon “What Castro Can Do” to return to the good graces of the United States: “He ought to say how sorry he is for all the pain he’s caused everybody, and beg us to forgive him. Tears wouldn’t hurt either.”

Fifty-five years later, advocates of the much-welcomed policy démarche make a persuasive case for change on the basis that punitive policies of political isolation and economic sanctions have failed to produce the desired outcomes. Obama said the new policy will serve to “end an outdated approach,” that “hasn’t worked” and emphasized the need “to try something different.”

Democratic Senator Patrick Leahy similarly praised the end of “53 years of a policy that has not worked,” a sentiment shared by Republican Senator Jeff Flake: “It’s time to try something new.”

Few would dispute the conclusion that the policy has not “worked.” But it is also true that proponents for a change from “an outdated approach” should tread warily. In Cuba it does not require much of a political imagination to infer ominously the larger meaning of pronouncements that justify a new policy on the basis that the old policy “has not worked.” Not worked at what, regime change? Does the mantra to try “something different” imply a different path to regime change?

The official rationale for policy change is very much informed with instrumental purport, advanced on the grounds that normal diplomatic relations will provide the United States with the opportunity to “to have an impact on the future of Cuba,” as Democratic Senator Richard Durbin phrased it.

|

| This cartoon appeared in Puck in September of 1898, upon the conclusion of the Spanish-American War. The bottom caption on the original read: "Taking Cuba from Spain was easy. Preserving it from over-zealous Cuban patriots is another matter." The question of how the U.S. seeks to insert itself into Cuban affairs still remains. Image provided by author. |

Obama was unambiguous about U.S. goals, noting that engagement offers “the opportunity to influence the course of events.” Instead of a punitive policy designed to impoverish the Cuban people, the new policy seeks to empower the Cuban people, to separate them from “dependency” on their government as a means of “transition to democracy.”

The aphorism that the more things change, the more they remain the same seems to be on full display. Old habits are indeed difficult to break.

Americans persist in seeking to insert themselves into Cuban internal affairs, the Cubans insist on defending self-determination, vowing never to “renounce the ideas for which it has struggled for more than a century.” The policy change announced on December 17 appears to be less a change of ends than of means.

The euphoria greeting the joint announcements has subsided. It is now apparent that “normalization” will proceed in small increments, slowly. Normalization takes many forms, of course, and assumes many guises. It could hardly be otherwise.

Fifty-five years of “long-strained relations” do not readily allow easy access to pathways to “normal” relations. Progress will be registered in details, for indeed that is where the devil resides–and where the history lurks.

Benjamin, Jules R. The United States and the Origins of the Cuban Revolution: An Empire of an Empire of Liberty in an Age of National Liberation. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1991.

Bonsal, Philip W. Cuba, Castro, and the United States. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1971.

Brenner, Philip. From Confrontation to Negotiation: U.S. Relations with Cuba. Boulder: Westview Press, 1988.

Castro Mariño, Soraya M. and Ronald W. Pruessen., eds. Fifty years of Revolution: Perspectives on Cuba, the United States, and the World. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2012.

Gleijeses, Piero. The United States and Castro's Cuba in the Cold War. New York : Oxford University Press, 2013.

Guggenheim, Harry F. The United States and Cuba: A Study in International Relations. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1934.

Hernández, José M. Cuba and the United States: Intervention and Militarism, 1868-1933. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1993.

Leonard, Thomas M. Encyclopedia of Cuban-United States Relations. Jefferson, N.C. : McFarland & Co., 2004.

LeoGrande, William M. and Peter Kornbluh. Back Channel to Cuba: The Hidden History of Negotiations between Washington and Havana. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2014.

Morales Domínguez, Esteban and Gary Prevost. United States-Cuban Relations: A Critical History. Lanham, Md.: Lexington Books, 2008.

Morley, Morris H. The Imperial State and Revolution: The United States and Cuba, 1952–1986. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

Paterson, Thomas G. Contesting Castro: the United States and the Triumph of the Cuban Revolution. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Schoultz, Lars. That Infernal Little Cuban Republic: The United States and the Cuban Revolution. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

Smith, Earl E.T. The Fourth Floor: An Account of the Castro Communist Revolution. New York: Random House, 1962.

Smith, Wayne S. The Closest of Enemies: A Personal and Diplomatic Account of U.S.-Cuban Relations Since 1957. New York: W.W. Norton, 1987.

Welch, Richard E. Response to Revolution: The United States and the Cuban Revolution, 1959-1961. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1985.