Every holiday season, at least for the last 70 years or so, the red and green plant that most Americans associate with Christmas is everywhere. In fact, since 2002, December 12 has been known as Poinsettia Day, created by Congress to honor the passing of Paul Ecke, Jr., who helped commercialize the plant in the United States in the middle of the twentieth century. The lawmakers who created the holiday probably did not stop to reflect on the troubled start to Mexican-U.S. relations.

The date itself was chosen to commemorate the 1851 death of Joel Roberts Poinsett, the nation’s first ambassador to Mexico. In the late 1820s, he took the plant—known as the cuetlaxochitl in Nahua and the flor de nochebuena in Spanish—from the Mexican state of Guerrero and introduced it to Americans, who marveled at its foliage and began calling it the poinsettia.

The “holiday” is especially significant in 2023. Ten days prior marks the 200th anniversary of the Monroe Doctrine, a foreign policy announcement that set the stage for two centuries of rocky relations between the U.S. and Mexico. This announcement, written by Secretary of State John Adams and buried in James Monroe’s presidential address to Congress, claimed the entire hemisphere for the United States. The following year, the Monroe administration appointed Poinsett as the nation’s first ambassador to Mexico.

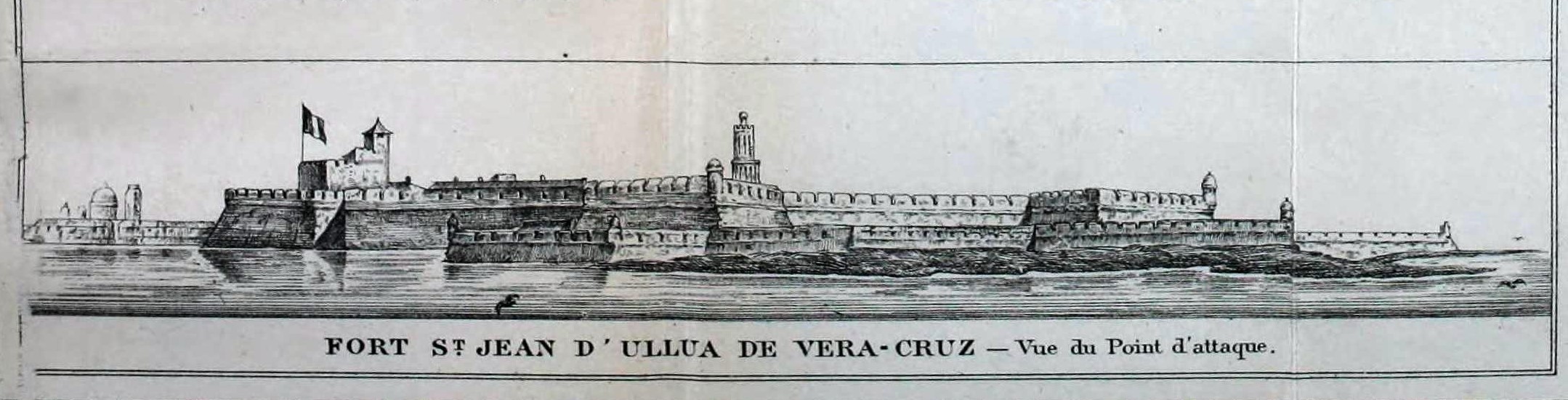

This appointment was an inauspicious start to diplomatic relations between Mexico and the United States. Poinsett arrived in Mexico in the spring of 1825, and almost immediately instigated a general distrust of American interference. His first stop was San Juan de Ulúa, the last site of Spanish military occupation in Mexico, to meddle in the negotiations between a Mexican and Spanish commander.

While he did nothing to change the outcome of Spain’s surrender, he set the tone.

Next, he visited the estate of a wealthy Philadelphia merchant to discuss Americans’ financial claims on the Mexican government, as well as opportunities for investing in mining ventures south of Mexico City.

Poinsett also helped establish a Masonic Lodge specifically to organize opposition to the ruling centralista party, which he saw as antithetical to U.S. interests because of its close ties to British business. When this rising opposition had some political successes, Poinsett used his Masonic connections to secure favorable plots of land for himself and his friends and establish an American-based mining company.

It was on a mining trip, in fact, that Poinsett admired the cuetlaxochitl and cut clippings to send to horticulturalists in the United States. Exactly where and how these clippings occurred is not quite clear, but on a trip south of Mexico City to assess the Tlalpujahua mines, he remarked on the beauty of the plants he saw, which Franciscan friars had been displaying at Christmas since the 1600s.

Several prominent horticulturalists in the United States later reported that Poinsett had sent them plants, and, by the mid-1830s, agricultural reports described a plant with brilliant scarlet foliage, “lately referred to as the poinsettia,” as having been introduced in 1828.

That year, Poinsett also supported, and possibly abetted, a coup in Mexico City. He and his political allies contested the presidential election of moderate Manuel Gómez Pedraza over their preferred candidate, Vicente Guerrero, whom Poinsett saw as more amenable to his financial interests. In what became known as the Acordada Revolt, some of Guerrero’s supporters occupied an arsenal and ransacked markets. After several days of fighting between the rebels and government forces, Pedraza fled and Congress declared Guerrero president.

Guerrero’s presidency meant that Poinsett’s closest Mexican ally, statesman Lorenzo Zavala, gained more economic and political influence. Once Guerrero took office, Zavala became minister of the treasury and received a large land grant in Texas, which he and Poinsett used to form a real-estate promotion firm called the Galveston Bay and Texas Land Company.

Newspapers in Mexico began reporting about Poinsett’s malicious interference.

In a document titled “La conducta de Mr. P,” the Mexican legation in Washington requested Poinsett’s removal from his post. Guerrero, despite once earning Poinsett’s endorsement, asked President Andrew Jackson to recall him.

Jackson instead allowed him to resign and in 1830 Poinsett returned to the United States, the same year that Jackson signed the “Indian Removal Act” into law. Several years later, Poinsett became Secretary of War and oversaw the violent dislocation of Native peoples as mandated by the “Removal Act.”

All of Poinsett’s experiences as a statesman convinced him that the United States should have a national museum to display the expanding government collections, including plant specimens. The gardens of the Smithsonian Institution that he advocated for now showcase thousands of the plant that bears his name.

The poinsettia/ cuetlaxochitl /flor de nochebuena has a long history that began for the United States two centuries ago in the wake of the Monroe Doctrine. Its brilliant foliage belies the dark start to the relationship between the United States and Mexico.

![]()

Learn More:

Flowers, Guns, and Money: Joel Roberts Poinsett and the Paradoxes of American Patriotism (University of Chicago Press, 2023)

Ana Romero-Valderrama, “La coalición pedracista: elecciones y rebeliones para una re-definición de la participación política en México (1826-1828)” (PhD. Diss. Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnologiìa, Mexico, 2011).

Jay Sexton, The Monroe Doctrine: Empire and Nation in Nineteenth-Century America (New York: Hill and Wang, 2011).

María Eugenia Vázquez Semadeni, “Del mar a la política: Masonería en Nueva España, México, 1816-1823,” Revista de Estudios Históricos de la Masonería Latinoamericana y Caribeña (Dec. 2015)

Torcuato S. Di Tella, National Popular Politics in Early Independent Mexico, 1820-1847 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1996).

United States' Mexican Company, Statement in relation to the United States' Mexican Company (Albany: Websters and Skinners, 1826).