Even as we go to press, the situation in Sudan continues to be fluid and dangerous. Mass demonstrations brought about the end of the 30-year regime of Sudan's brutal leader Omar al-Bashir. But what comes next for the Sudanese people is not at all certain. This month historian Kim Searcy explains how we got to this point by looking at the long legacy of colonialism in Sudan. Colonial rule, he argues, created rifts in Sudanese society that persist to this day and that continue to shape the political dynamics.

Listen to this podcast: Sudan: Popular Protests

Since December 2018, daily street protests have taken place across the Republic of Sudan. Protestors targeted the regime of Sudan’s longtime president, Omar al-Bashir, winning his ouster after three decades of rule on April 11, 2019.

Al-Bashir seized power in a military coup in 1989. While he did win election as president throughout his 30-year reign, Human Rights Watch calls those elections fraudulent.

Protesters near the Sudanese Army headquarters in Khartoum in April 2019.

On February 22, al-Bashir had delivered a nationally broadcast response to the protests. He opened on a conciliatory note, but then abruptly changed tone, declaring a one-year state of emergency and dissolving the government. Yet the protests persisted until he was finally forced from office.

These events join 1964 and 1985 as moments when Sudanese activists overthrew the country’s military regimes in nonviolent popular uprisings. The catalysts of the first two were civil wars (1955-1972 and 1983-2005) fought between the central Sudanese government troops and southern guerillas.

There are several immediate causes of the recent protests, which began in Atbara, a city in the northeast of the country, and quickly spread to other parts of the Sudan.

Public discontent had been building for many months over price increases for bread, medicine, and fuel; breakdowns in education and transportation systems; and a wide range of other economic hardships. Ongoing conflicts and political unrest in the western Sudanese state of Darfur and in the Blue Nile and South Kordofan states also played a role in sparking the popular uprisings.

In particular, Darfuri students and religious leaders have long been vocal critics of the al-Bashir regime. Sheikh Matar Younis, a blind religious leader from central Darfur delivered a sermon in August 2018 in Zalingei City, arguing that Sudan’s crises “can only be resolved when the Khartoum regime goes to the dustbin of history.”

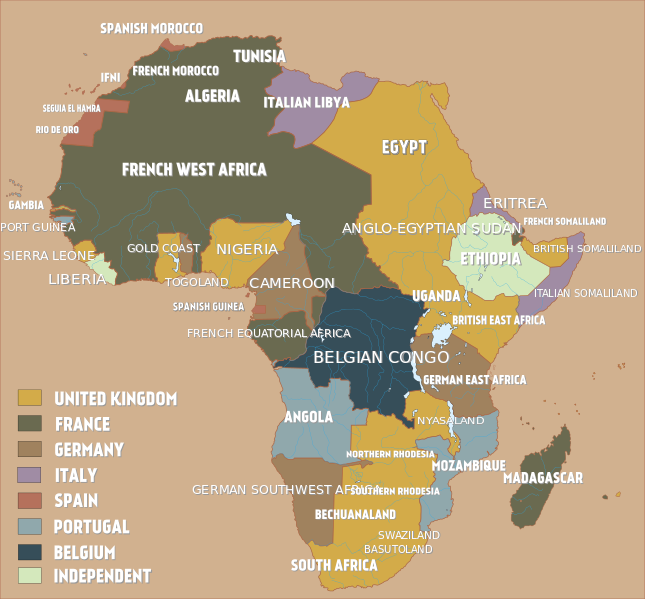

However, to understand fully today’s popular protests, we need to look all the way back to the Sudan’s colonial past. Post-independence conflicts in Sudan were largely caused by ethnic divisions created by the British colonial administration between 1899 and 1956. “Divide and rule” policies pursued by the British continue to haunt contemporary Sudan, both north and south.

Colonial Policy and Two Sudans

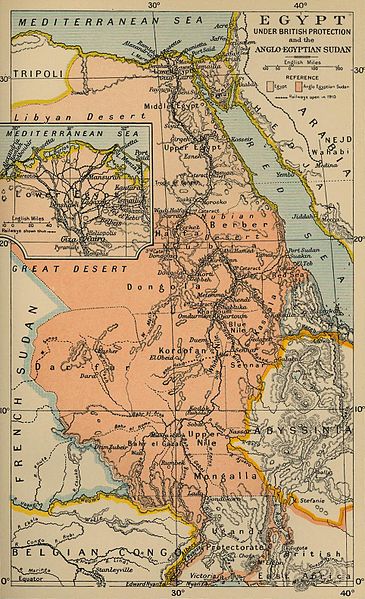

During most of the colonial period (1899-1956), Sudan was ruled as two Sudans. The British separated the predominantly Muslim and Arabic-speaking north from the multi-religious, multi-ethnic, and multilingual south.

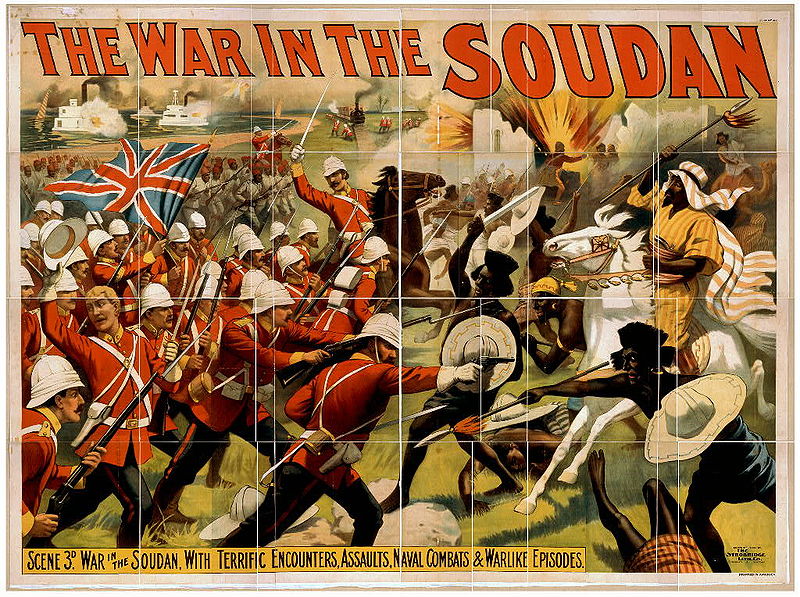

An 1897 lithograph depicting the Mahdist War (1881-1899).

The Sudanese peoples were masters of their own fate for one brief period in the modern era. From 1885 to 1898, the Nilotic Sudan was under the control of the Mahdiyya, a native northern Sudanese Islamist group that defeated the Turco-Egyptian forces occupying the region since 1821.

In 1898, however, the United Kingdom and Egypt conquered the Sudanese Mahdist state and instituted policies that continue to have lasting effects.

Britain did not occupy Sudan. Rather, it instituted a “divide-and-rule” policy. The UK and Egypt ruled present-day Sudan and South Sudan through a dual colonial government known as the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium (1899–1956). Britain was the senior partner in this administration, as Egypt itself was politically and militarily subordinate to Britain.

British Officers and Indian Infantry in Sudan around 1884.

Britian’s “divide-and-rule” policy separated southern Sudanese provinces from the rest of the country and slowed down their economic and social development. The British authorities claimed that the south was not ready to open up to the modern world. At the same time, the British heavily invested in the Arab north, modernizing and liberalizing political and economic institutions and improving social, educational, and health services. Western regions of Sudan, such as Darfur, were also neglected during this time.

The condominium’s educational policies reflected the separation of north from south. The British, until 1947, developed a government school system in the north, while Christian missionaries undertook educational matters in the south.

Khartoum University, established by the British in 1902.

In the north, the government invested in education, and school networks coexisted with Egyptian schools, missionary schools, community schools, and Sudanese private schools. In the south, various Christian missionary denominations established schools. Whereas Arabic and English were the mediums of instruction in northern schools, the linguistic situation was more complicated in the south, where local vernaculars, English, and Romanized Arabic were used in missionary schools.

The British placed northern riverine peoples in positions of power and authority, specifically the Shaigiyya, Jailiyyin, and Dongola groups. These groups continue to wield power and influence today. Al-Bashir is from the Jailiyyin group. Consequently, the British created a social hierarchy in Sudan that resulted in distrust, fear, and conflict between the various Sudanese peoples.

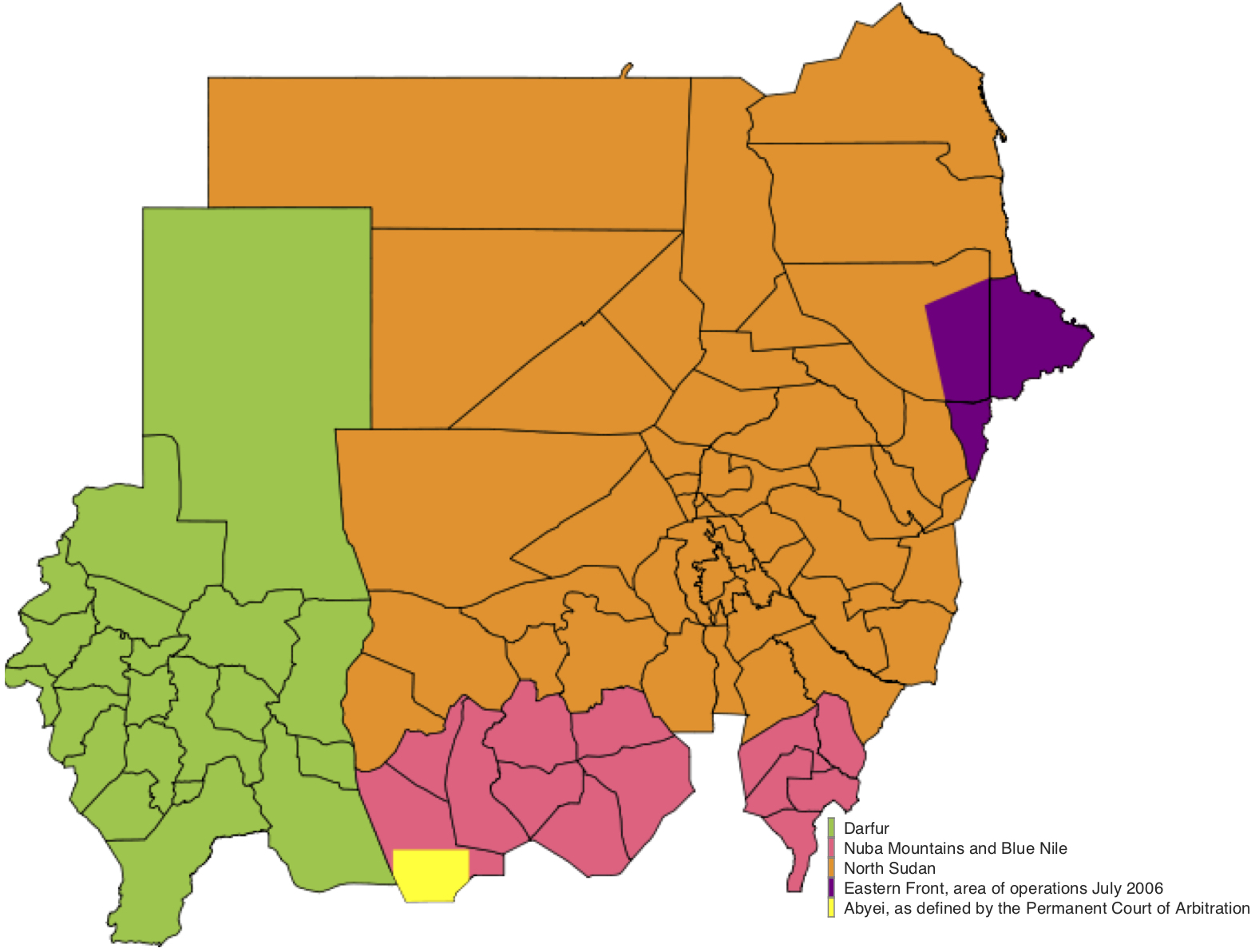

A political map of Sudan as of 2006.

The British encouraged Islamization and Arabization of the north through financial help for building mosques and pilgrimage travel for Muslims. In southern Sudan, however, Christian missionaries attempted to prevent the spread of Islam and to preserve a way of life they considered more authentic. Some scholars maintain that the British planned to attach southern Sudan to British East Africa, a British protectorate that became Kenya.

Another colonial experiment that slowed down development of southern Sudan was the “indirect rule” policy. In order to prevent an educated urban class and religious leaders from influencing social and political life in southern Sudan, the British authorities gave “power” to the tribal leaders and ruled through them. While the divide-and-rule policy separated the north and south, indirect rule divided the south into hundreds of informal chiefdoms.

British authorities implemented these policies by completely separating southern tribal units from the rest of the country. Northern officials were transferred out of the south, trading permits for northerners were withdrawn, and speaking Arabic and wearing clothing associated with Arab cultural traditions was discouraged.

An Independent, Divided Sudan

The southern provinces, sidelined during British rule, continued to be marginalized and underdeveloped in independent Sudan controlled by the northerners.

The Sudan Defense Force band in the 1940s.

The period of British rule in the south proved to be the longest the nation experienced without invasion or the large-scale use of force. However, while the British had prevented the oppression and exploitation of the southern Sudanese by their northern countrymen, they did little to help the south develop economically or otherwise participate in the modern world. Regional differences resulted in a deeply divided and economically differentiated Sudan—an Arab-dominated north, economically and politically stronger than the underdeveloped African south.

In 1953, with its grasp on all its colonial possessions slipping, the British granted a degree of self-determination to the Sudanese. At the end of 1955, the Sudanese parliament unilaterally declared independence and the British were in no position to stop it. Britain recognized the new nation on January 1, 1956, and the United States followed shortly thereafter.

Independence, however, was achieved in the context of deep division.

The British had separated the northern and southern Sudanese from each other culturally and socially without separating them politically. As a result, when the British abdicated, the northerners were likely to attempt to assimilate the southerners by force. This, in turn, has rendered a southern resistance movement inevitable.

The tension and mistrust between the northern and southern Sudanese that had been nurtured over decades culminated into a large-scale armed conflict in the mid-1950s. Fearing marginalization by the more populous and developed north, southern army officers mutinied in 1955. This was the beginning of the first long civil war, which did not wind down until the early 1970s and resulted in an agreement to give the south more self-governance.

Peace was short-lived. Civil war between the government in the north and rebels in the south broke out again in 1983. During the period between the two wars, however, economic prospects in the south changed dramatically. Oil was discovered there in 1978 and Sudan exported its first barrels in 1999.

Oil fields and infrastructure in Sudan and South Sudan in 2014.

The second civil war ended with the ratification of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement in 2005. Southern autonomy was implemented in the same year. The South voted for independence in a referendum and became the Republic of South Sudan in July 2011.

Thus, the southerners separated, taking their oil with them. The north was left with its refineries, pipelines, and resultant faltering economy. The creation of South Sudan as an independent nation also meant that Sudan itself was a more ethnically, religiously, and linguistically unified nation. The British policy of divide and rule, pitting south against north, seemed to have ended in a divided nation.

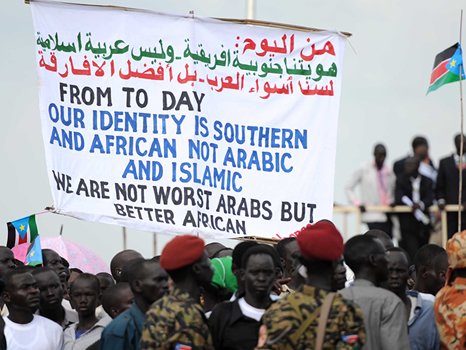

A supporter of secession in 2011.

Al-Bashir may be blameworthy for the privations experienced by the Sudanese throughout his 30-year presidency, but he also is a symbol of the role that colonialism has played in the fortunes of the Sudan. His people, the Jailiyyin, are among the riverine Arab groups that British officials placed in power during the condominium.

During his time as president, the southern, western, and eastern parts of Sudan received little investment or development whereas the north was developed. In fact, the Sudanese classed these regions as the Munataq Hamashiyya, the “marginalized regions.”

Crisis in Darfur

Even as the second civil war was winding down, conflict arose in another part of Sudan. In 2003, the war in Darfur, the westernmost region of Sudan, began. In February, Darfuri insurgents launched an attack on the government, which responded with a brutal campaign of ethnic cleansing of non-Arab Darfuris.

Darfur refugees carrying food home from a World Food Program center in 2007.

The United Nations has estimated that in the first five years alone, 300,000 people were killed by air raids, shelling, and attacks on villages. People fled to camps and sought refuge abroad. To date, more than 300,000 Sudanese refugees reside in camps in neighboring Chad. The International Criminal Court has indicted al-Bashir for war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide for his actions in Darfur.

While a ceasefire was negotiated in 2010, the war never truly ended. Despite reports about reduced insecurity in the Darfur region and a decrease in the number of clashes between government forces and armed movements, camps for displaced people remain.

Makeshift shelters at an Internally Displaced Persons camp in South Darfur in 2005.

According to Human Rights Watch, the conflict and ensuing insecurity continues to leave more than 2.7 million displaced people in Darfur. Only in April of 2018 did the first large-scale voluntary returns from Chad take place.

Fighting continues in Darfur between the rebel Sudan Liberation Movement and government supported militiamen known as the Rapid Support Forces. The Rapid Support Forces (RSF), created in 2013 specifically to fight armed rebel groups in Darfur, are under the control of the Sudanese National Intelligence and Security Services (NISS), which was accountable to al-Bashir.

The Sudan Liberation Movement has accused the RSF of using hunger as a weapon by destroying crops in order to starve the residents. In addition, the Dabanga News agency reported that government forces stationed in South Darfur have engaged in periodic shelling of the area and killed several civilians.

This war was also a legacy of the British colonial policies in the Sudan. Darfur, unlike South Sudan, is predominately Muslim. Yet, like South Sudan, it is multi-ethnic and multi-lingual. The war was characterized in the Western media as a war between Arabs and Africans in the region. But this construction oversimplifies. Rather, the roots of the war again lie in the relative underdevelopment of and lack of investment in the south.

The End of Al-Bashir, the Beginning of Democracy?

In October 2017, the Trump administration added legitimacy to al-Bashir’s presidency when it lifted economic sanctions that had been in place for 20 years. The U.S. State Department noted that while al-Bashir’s government was not perfect, there were enough signs of progress to warrant the end of the sanctions.

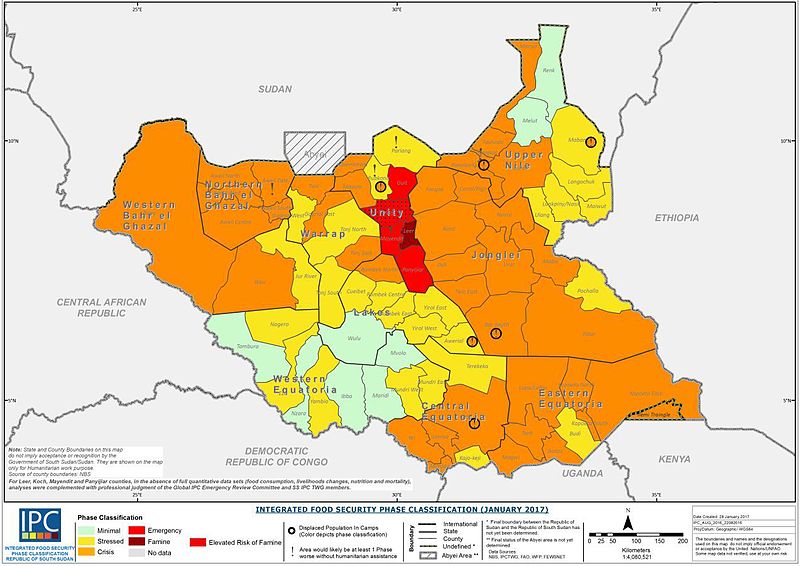

A 2017 map of South Sudan’s food insecurity situation.

These signs included cooperation with the United States in the latter’s global war on terrorism, curbing destabilizing activities in South Sudan, and ending attacks against civilians in Darfur.

Sanctions relief did not dramatically improve the economic situation and the government instituted austerity measures at the end of last year. These resulted in an increase in the prices of staple foodstuffs because of subsidy cuts to comply with World Bank and IMF measures.

A Save the Children worker dispensing monetary aid in 2008 to families in South Sudan.

Public anger in Sudan had been building up over rising prices and other economic hardships. Sudan’s overall economy has been hit hard, particularly after the south separated from the north in 2011, taking with it about 75% of the country’s overall oil revenues. Over the past year, the value of the Sudanese pound has dropped steadily against the dollar. In December 2018, the Central Bank of Sudan issued a decision to limit cash withdrawals at ATMs. A recent printing of new currency by the Central Bank of Sudan was an attempt to end hyperinflation, coupled with a chronic shortage of hard cash.

The protests began in response to food and fuel shortages, but then morphed into protests calling for al-Bashir to relinquish power.

In spite of his removal in February, protests and sit-ins continue and the situation changes daily. The army generals who staged the coup have formed what they call a Transitional Military Council (TMC) and are engaged in negotiations with the main opposition group, the Alliance of Freedom and Change.

The anti-government protesters state they will continue their acts of civil disobedience until free and transparent elections implement civilian rule. In recent days, there has been a countrywide strike to encourage the army to hand over power to a civilian government. This strike is a response to the mass killing of protesters by the government-backed Rapid Support Forces.

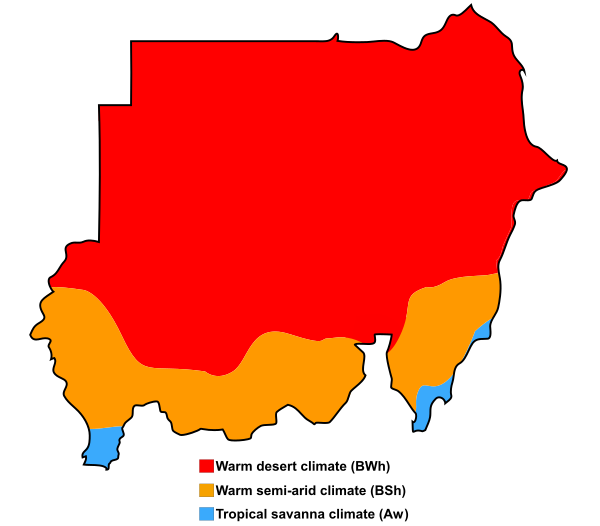

A map of the climate in Sudan.

The last time the Sudanese people ousted a military regime, in 1985, protests were limited geographically—mostly centralized in Khartoum, the capital, and directed by elites.

The current protests are different because they began outside the capital and spread to the provinces. Less than a week after the first protests in Atbara, they spread across the entire country and were met with violence by the Sudanese Security Forces. Activists estimate that at least 50 people have been killed since the start of the protests.

With al-Bashir gone, whatever government assumes control in Khartoum will face significant long-term challenges. Climate change, manifested particularly in desertification, combined with an expanding population will strain agricultural resources and threaten food security. Sudan has recently witnessed increases in temperature, floods, rainfall variability, and droughts.

For rural populations, unreliable rainfall, low productivity, and small landholdings are major contributors to poverty and malnutrition. A third of children are underweight from chronic malnutrition. Poverty is endemic in isolated rural areas, and as a result, millions of people have fled areas on the periphery for Khartoum.

Currently in Sudan, an estimated 45% of the population live below the poverty line, with poverty rates higher in rural areas (55%) than in urban areas (28%). High unemployment rates (17%) as well as low employment opportunities contribute to the economic disparity found in many regions of Sudan.

Protests that began as a popular uprising against high fuel and flour prices have “turned into a broad resistance movement against a corrupt and despotic regime,” in the words of the opposition Sudan Congress Party leader Omer El Degeir. He added that the only solution is a “reconstruction on new and sound basis that recognizes the diversity of Sudanese reality and improves its management.” If that happens, the harmful legacy of divide and rule could finally be defeated.

Read these fascinating Origins articles for more on Africa: the Darfur Conflict; A New Congo Crisis; A Century of HIV; Understanding Boko Haram; Islamist Groups in Egypt; Africa and China; Ethiopia and Nile River Tensions; Politics in Senegal; Piracy in Somalia; Violence and Politics in Kenya; Women in Zimbabwe; and Sport in South Africa.

Listen to this podcast: Sudan: Popular Protests; Museums and Cultural Heritage Repatriation; and Sub-Saharan Africa.

Berridge, W.J. Civil uprisings in Modern Sudan: The Khartoum Springs of 1964 and 1985 (Bloomsbury Academic Press, 2015).

Beshir, Omer Mohamed. The Southern Sudan: A Background to Conflict (New York: Praeger, 1968).

Beshir, Omer Mohamed. Revolution and Nationalism in Sudan (London: Collings, 1974).

Deng, Francis. War of Visions: Conflict of Identities in the Sudan (Washington DC: The Brookings Institution, 1995).

de Waal, Alex and Julie Flint. Darfur: A New History of a Long War (London: Zed Books, 2008).

de Waal, Alex and P.M Holt. A History of the Sudan: From the Coming of Islam to the Present Day (London: Longman, 2000).

Gallab, Abdullahi A. The First Islamist Republic: Development and Disintegration of Islamism in Sudan (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2008).

Holt, P.M. Mahdist State in the Sudan: A Study of its Origins, Development and Overthrow (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1958).

Radio Dabanga, https://www.dabangasudan.org/en.

Sudan Tribune, http://www.sudantribune.com.