Ever since Joseph Conrad set his 1899 novel The Heart of Darkness there, Congo has struck many observers as a paradox. An enormous territory located in the very core of Africa, the Democratic Republic of the Congo is so rich in natural resources that it ought to be among the most prosperous countries on the continent. Yet, as historian Sarah Van Beurden explains this month, patterns of political repression, violence, and economic exploitation established in the 19th-century colonial era continue to shape dynamics in Congo today.

A recent BBC headline read, “Paradise Papers Documents Raise Questions over African Mining Deal.” A story in the German Süddeutsche Zeitung was poetically titled “ The Broken Heart of Africa .” These headlines were part of the recent flurry of reporting on the Paradise Papers, a cache of documents detailing the way corporations hide profits through tax havens and avoidance.

They gave new insight into the convergence of an international network of business interests and the political establishment in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), exposing the struggle for access to and exploitation of a large copper and cobalt mine in the Katanga region.

The articles appeared at a time when elections in the Congo were almost a year overdue. Opposition groups, civil society organizations, the Catholic Church, and international organizations are among those who have called for current president Joseph Kabila to step down.

It has become a cliché to contrast the Congo’s tremendous economic resources with the crushing poverty much of its population endures. Despite a rise in GDP, 80% of the population still lives on less than $1.25 per day. This in a country that possesses the world’s largest supply of industrial diamonds, the second largest supply of iron and more than 10% of the global supply of copper. It also has zinc, tin, gold, silver, nickel, limestone, tungsten, uranium, and coltan (crucial in electronic products).

Workers in a wolframite and casserite mine in Congo in 2007.

The reason that these vast natural riches have not translated into a more widely shared prosperity for Congolese people lies in global patterns of economic exploitation and the way those have been intertwined with political authoritarianism. That intertwining happened in the late 19 th century age of imperialism and it continues to shape Congo today.

Colonial Congo

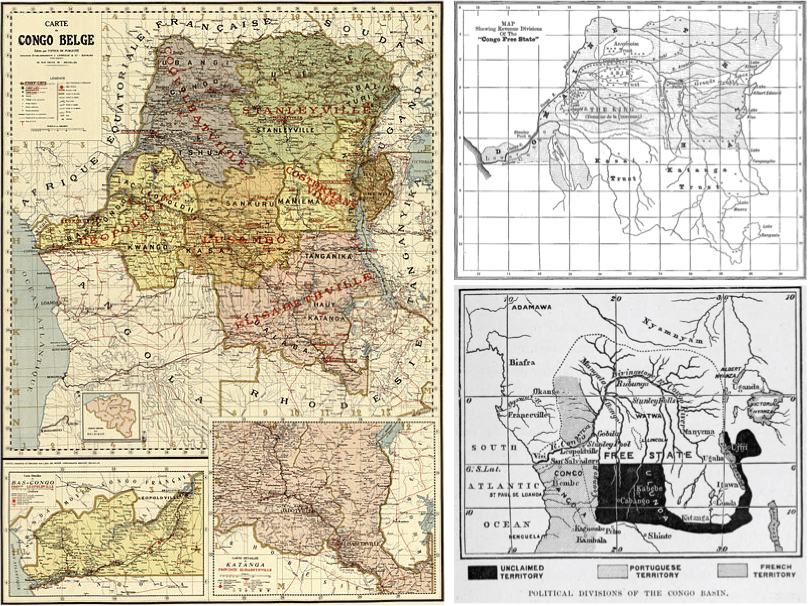

The Congo Free State, a vast area covering much of central Africa, was the dream of Belgian King Leopold II. In 1885, he established control over a territory that had never been a single political or cultural region before. With only a small number of colonial state officials to administer an area of over 900,000 square miles, Leopold II relied on a set of colonial companies to help run this vast territory.

A map of the Congo Free State created sometime after 1920 (left). A 1906 map showing revenue divisions in the Congo Free State with crosses marking the locations of documented atrocities (top). An 1885 map from H.M. Stanley’s book, The Congo and the Founding of its Free State; A Story of Work and Exploration (bottom).

Rule over Leopold’s personal fiefdom was brutal. Together with the practices of the colonial companies, his reign established long-term patterns of economic exploitation and political authoritarianism.

The principle of company rule was prominent in the Belgian Congo. Major companies, usually closely aligned with the colonial state through personal or financial ties, exercised considerable influence over the colonial system locally, but also through its financial and industrial barons in the metropole.

Ivory, wood, and rubber were the first resources brought out of Congo to the international market. Later, palm oil and agricultural crops such as coffee joined them. But as the 20th century wore on, minerals—many of them crucial to modern industries—more than other resources became the source of wealth and conflict.

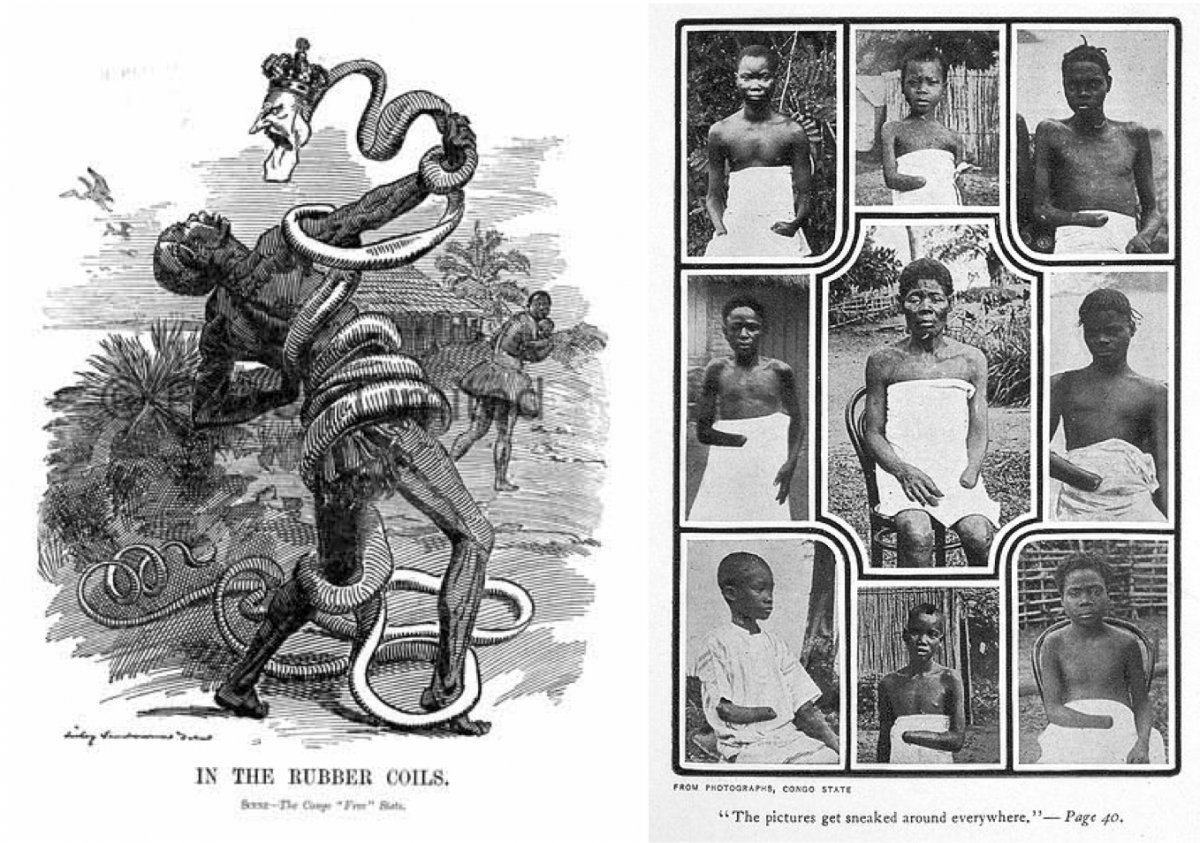

A 1906 political cartoon depicting King Leopold II of Belgium as a snake entangling a Congolese rubber collector (left). Pictures taken by British missionary Alice Seeley Harris in 1904 in support of the campaign against the abuses of the rubber exploitation in Leopold's Congo. Shown here as reproduced in Mark Twain's 1905 "King Leopold's Soliloquy."

Although gold was found near the border with today’s Uganda and diamonds were—accidentally—first found in the Kasai region in 1907, the heart of the country’s mining wealth is the Katanga region, along the northern border with Zambia. Copper was “discovered” there in the late 19th century (local populations had in fact been mining and smelting copper since the 5th century). Add to this zinc, tin, nickel, cobalt, manganese, coal, and uranium, to name but a few, and the profits to be reaped from mining in Congo are simply overwhelming.

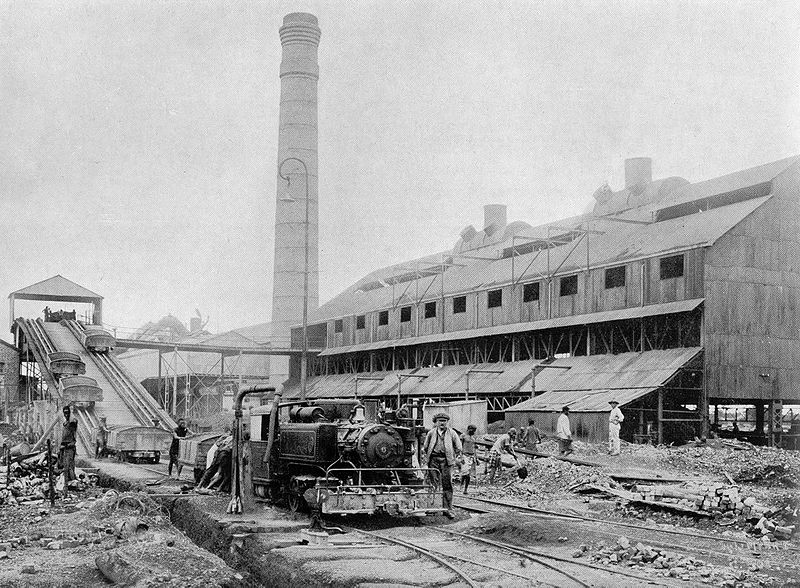

Large-scale industrial mining started in the early 20th century, mostly through the system of colonial companies. The best known was the Union Minière du Haut Katanga (UMHK, Mining Union of Upper Katanga), which controlled copper mines in the Katanga region and functioned very much like a state within a state. The profits, however, flowed out of the Congo back to Belgium and into the pockets of the industrial and political elite there. Europeans became rich as minerals, commodities, and wealth were stripped from the Congolese people.

A Union Minière du Haut Katanga ore processing plant in 1917.

From 1885, this combination of business exploitation and the king’s authoritarianism generated considerable violence towards the Congolese. It came in many forms—labor coercion, the suppression of local political, social, and cultural traditions, forced migration, and physical beatings and mutilations. It remained embedded in the fabric of Belgian colonialism even after the Belgian state, under pressure of the international outcry over the abuses of Leopold II’s rubber production, took over the colony in 1908.

The violence associated with exploitation produced resistance in return. Religion played an important role, particularly in rural resistance against oppressive cash crop regimes, labor recruitment, and conscription practices. In an environment violently hostile to resistance, religious discourse was a prime avenue for the expression of identity and discontent.

But resistance took other forms as well. In 1931, for example, the Pende people of the Southwestern Kasai rose up against the Huileries du Congo (a Lever Brothers’ enterprise, and predecessor of today’s Unilever). The concessionary company exploited the region as a large palm oil plantation and subjected the Pende to a harsh labor regime. As the most vulnerable link in the global commodity chain, the palm oil laborers felt the Great Depression keenly in reduced wages, growing production pressure, and increased taxes.

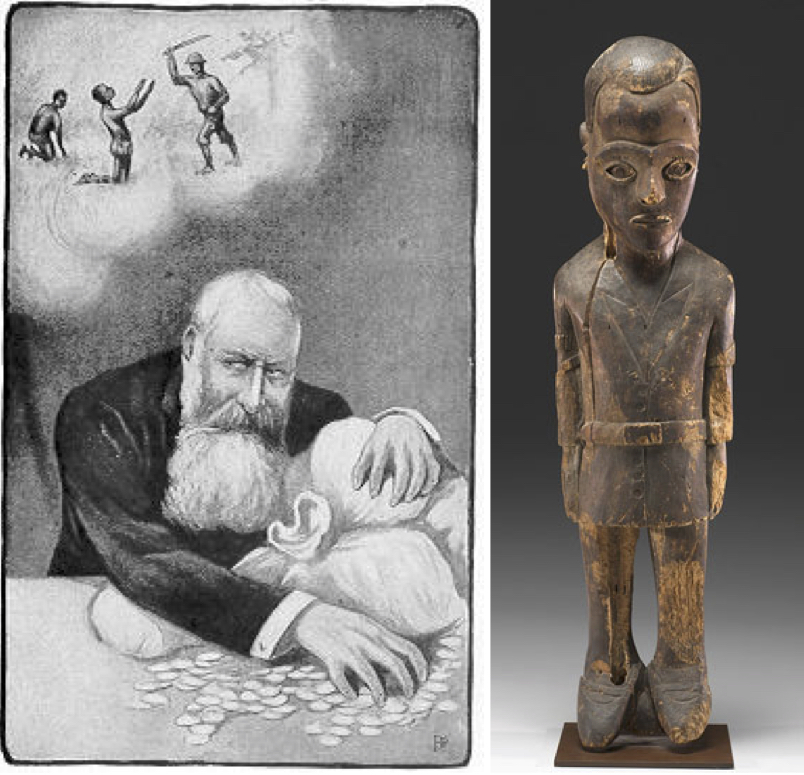

The Pende sought solace in spiritual practices of resistance and eventually all-out revolt and the killing of a tax collector. By the time the revolt was suppressed, several hundred (between five hundred and a thousand, reports vary) Pende were dead, and strict control was exercised over the appointment of local chiefs.

A 1905 caricature of King Leopold II with his earnings from the Congo Free State and exploited workers in the background (left). A statue of a despised Belgian colonial agent, Maximillen Balot, after Congolese in the Pende area killed him in 1931 (right). [Diviner's Figure Representing Belgian Colonial Officer Maximillen Balot, 1931, Pende Culture (Democratic Republic of Congo) Wood, Height 24 5/8 in. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond; Aldine S. Hartman Endowment Fund. Photo: Travis Fullerton © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.]

Independence and the First Congo Crisis

When Congolese resistance to the colonial system burst out in the open in late 1959, and independence became inevitable, the moment seemed like a time of longed-for possibilities. Just as quickly it became painfully clear that the legacy of the entanglements of a colonial system based on political authoritarianism and economic exploitation would not easily be undone.

As soon as independence negotiations began, opinions differed as to what decolonization would entail. Belgians wanted to develop an independent political system much like their own. The Congolese demands included the restitution of their economic and cultural resources including Congolese art objects in Belgian museums.

Take, for example, UMHK. By 1960, the conglomerate was co-owned by the Société Générale de Belgique, the national bank, and the colonial state. Deeply embedded in elite Belgian industrial and political circles, it generated considerable wealth for Belgium and its economy. The Belgians proved reluctant to hand over their part of the ownership shares of the company to the Congolese, and dragged its feet long enough to allow for a restructuring of the company and its finances. It proved to be the start of a long dispute over economic decolonization.

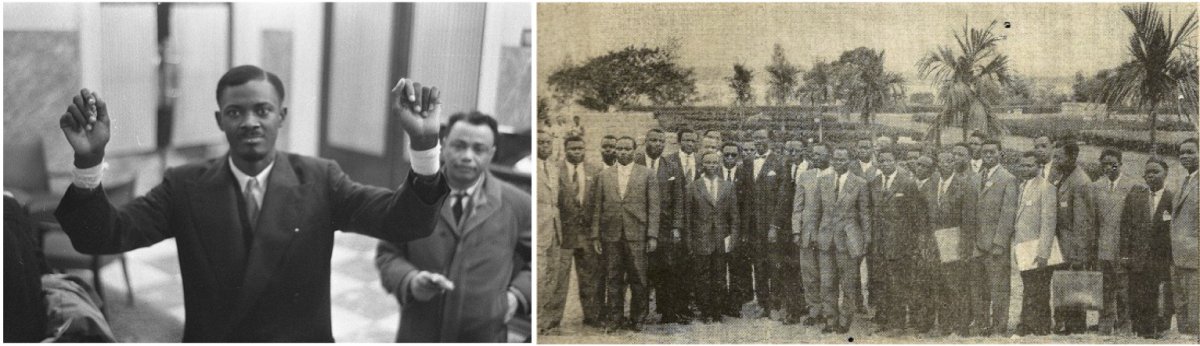

Future Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba showing the injuries to his wrists from shackles after being imprisoned in 1960 (left). Patrice Lumumba and his cabinet immediately following his swearing-in ceremony in 1960 (right).

Within months of official independence on June 30, 1960, the fragile democratic system found itself under threat, when the first democratically elected Prime Minister, Patrice Lumumba, was killed by a conspiracy of Belgian, American, and Congolese actors.

A first military coup by Joseph-Désiré Mobutu took place in September 1960 and a series of regional uprisings and secessions unfolded. The combination of hasty independence, a continued system of colonial exploitation, Cold War tensions, and interventions in order to assure access to mining resources meant the newly created and fragile democratic system soon fell victim to manipulation, outside interference, and renewed authoritarianism.

Congo Becomes Zaire

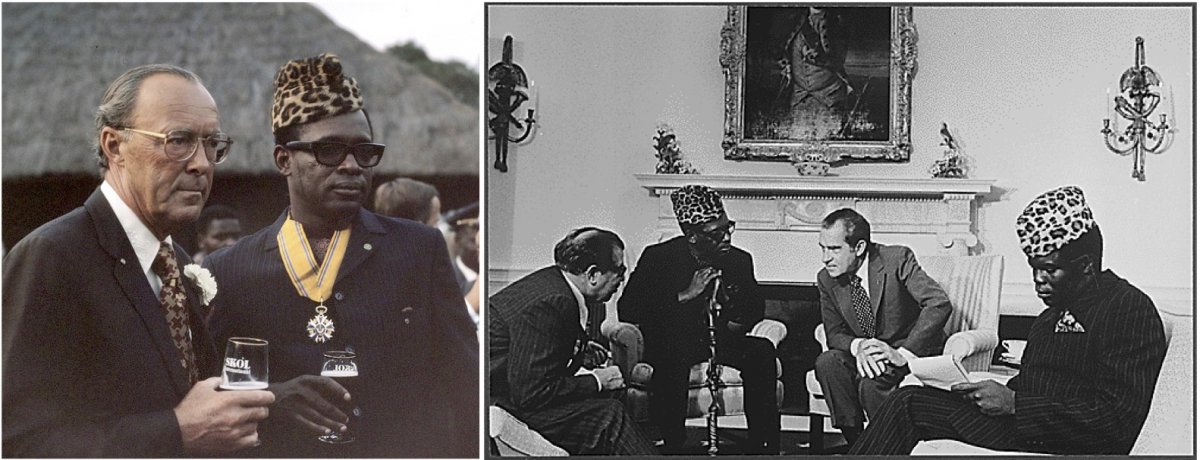

Mobutu became the permanent head of state after his second military coup in 1965 and remained in power until 1997 in one of the longest-reigning African dictatorships. Considered a safe choice and a guarantor of stability by his Western supporters, his relationship with Belgium was soon complicated by his actions to secure the country’s economic resources. The result was simply to reinforce the intertwined nature of economic exploitation and political authoritarianism, established by Belgians.

A journalist, military man, and former collaborator of Lumumba (in whose death he had a hand), Mobutu had considerable popular and foreign support after the 1965 coup. His pursuit of economic nationalization targeted the former colonial companies and foreign-owned businesses at large. After what the regime considered unsatisfactory progress on the state holdings in the UMHK, a 1966 law declared the state the owner of all mineral and mining rights in the country. This was followed a year later by the nationalization of the UMHK (renamed Gécamines).

Joseph-Désiré Mobutu and Dutch Prince Bernhard in 1973 (left). Mobutu and President Richard Nixon in Washington, D.C. in 1973 (right).

Nationalization did not result in a democratization of access to and control over the country’s resources, however. Instead, the previous Western elite were simply replaced by a national elite with deep ties to the Mobutu regime.

This process pervaded political life, where the centralization of and access to power went hand in hand with increased authoritarianism. A one-party system was created in 1970, and the centralization of power was supported by a cultural politics aimed at increasing the population’s sense of national identity, tying it to the regime’s version of sovereignty.

A political badge with the image of Joseph-Désiré Mobutu from the 1980s (left). A shirt with Joseph-Désiré Mobutu’s portrait printed on it (right).

The authenticity campaign promoted a national form of dress, so-called Bantu names rather than Christian or Western ones, and the renaming of the country as Zaire. Popular support for the regime was relatively high in the first decade, but declined steadily with a rise in political oppression and in the personality cult surrounding Mobutu.

A crash of global copper prices in the mid-seventies also revealed the lack of fundamental change in the economic system and initiated several decades of decline in people’s standard of living.

The decline of state infrastructure and the control by a small elite led many Zairians to develop alternate economic and social systems for survival, creating an informal economy on which the majority of the country’s citizens continue to rely.

Zairian currency from the 1970s.

Despite the regime’s increasing repression, resistance continued, with university students taking a prominent role. A combination of resistance, political opposition, local and region-wide conflicts, and the disappearance of Cold War support ultimately allowed for the overthrow of the Mobutu regime by Laurent-Désiré Kabila.

The Great War of Africa

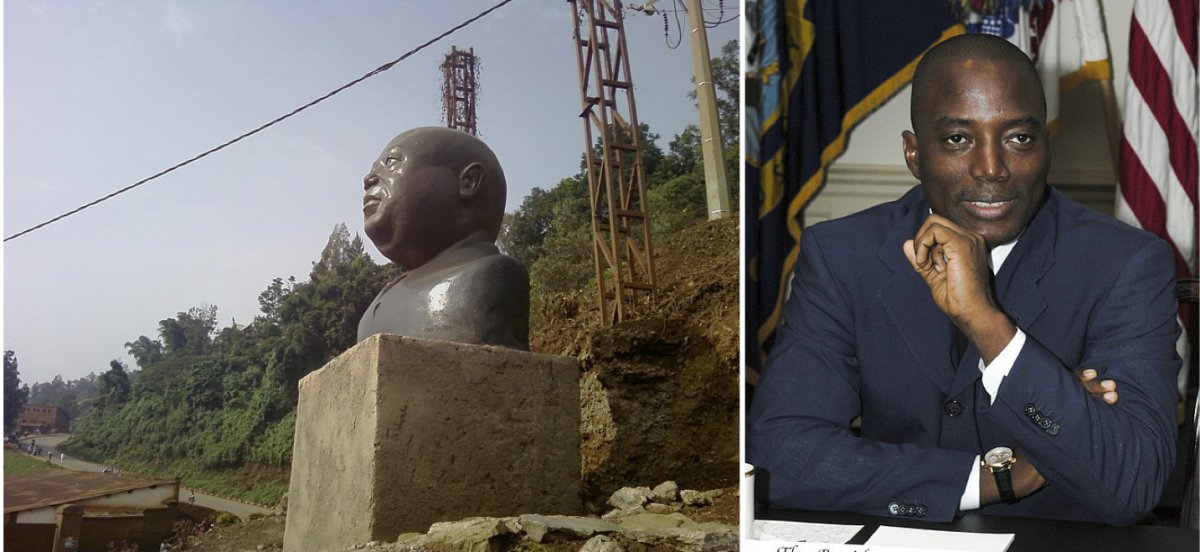

L-D. Kabila, the father of current president Joseph Kabila, seized the opportunity to topple the weakening Mobutu regime and its terminally ill leader in 1997, heavily supported by neighboring Rwanda, in a military campaign that swept the country from east to west. Kabila was a longtime rebel leader with roots in the Katanga province who managed to stay out of Mobutu’s reach, in part by moving his family to Tanzania.

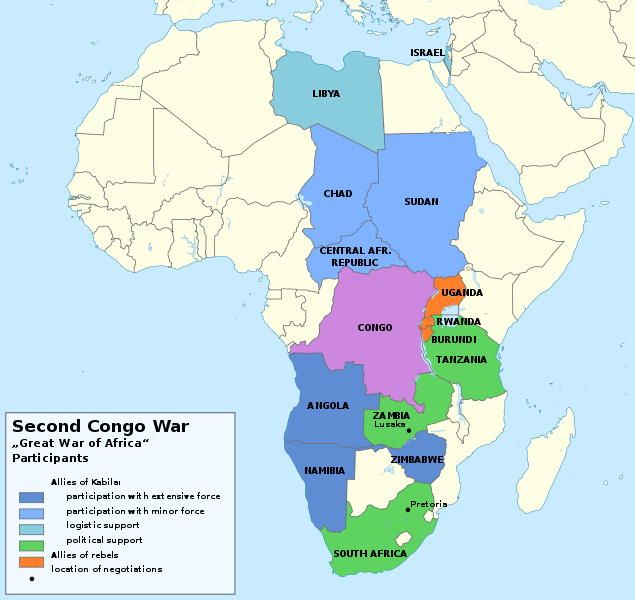

The conflict this invasion triggered in 1996 and 1997, and the subsequent conflict from 1998 to 2002, have become known as the “Great War of Africa” because many of the region’s countries were drawn in and because the death toll was staggering, likely topping several million. A major cause of the war originated in the Rwanda Genocide , which triggered the flow of about two million refugees, mostly Hutus, from Rwanda into refugee camps in the eastern part of the country.

A bust of Laurent-Désiré Kabila (left). President Joseph Kabila in 2003 (right).

Subsequent interventions by the Rwandan and Ugandan armies in pursuit of these refugees, who were (rightly) suspected of including members of the Interhamwe militias responsible for the genocide, along with local conflict caused by the presence of the refugees, in addition to the hollowed-out condition of the Zairian state and army meant that the coalition of forces, led by Rwanda and Uganda but including Laurent-Désiré Kabila and his troops (a significant percentage of whom were child soldiers), reached the capital of Kinshasa in a mere seven months. Mobutu left for longtime ally Morocco, where he died soon after.

The relationship between L-D. Kabila (who renamed the country Congo again) and Rwanda and Uganda soon soured, and the latter started a new military campaign in 1998, aiming to replace their former ally with the involvement of a different Congolese rebel group.

Congolese soldiers in 2001 during U.S. Congressman Frank Wolf’s visit (left). Former child soldiers in Congo in the early 2000s (right).

This time, however, the Congolese leader was saved by a coalition of Southern African forces, including Zimbabwe , Namibia, and Angola. In addition, Sudan and Libya sent support, while the rebels and Rwanda and Uganda received some assistance from Burundi. The new Congo crisis had become a continent-wide conflict.

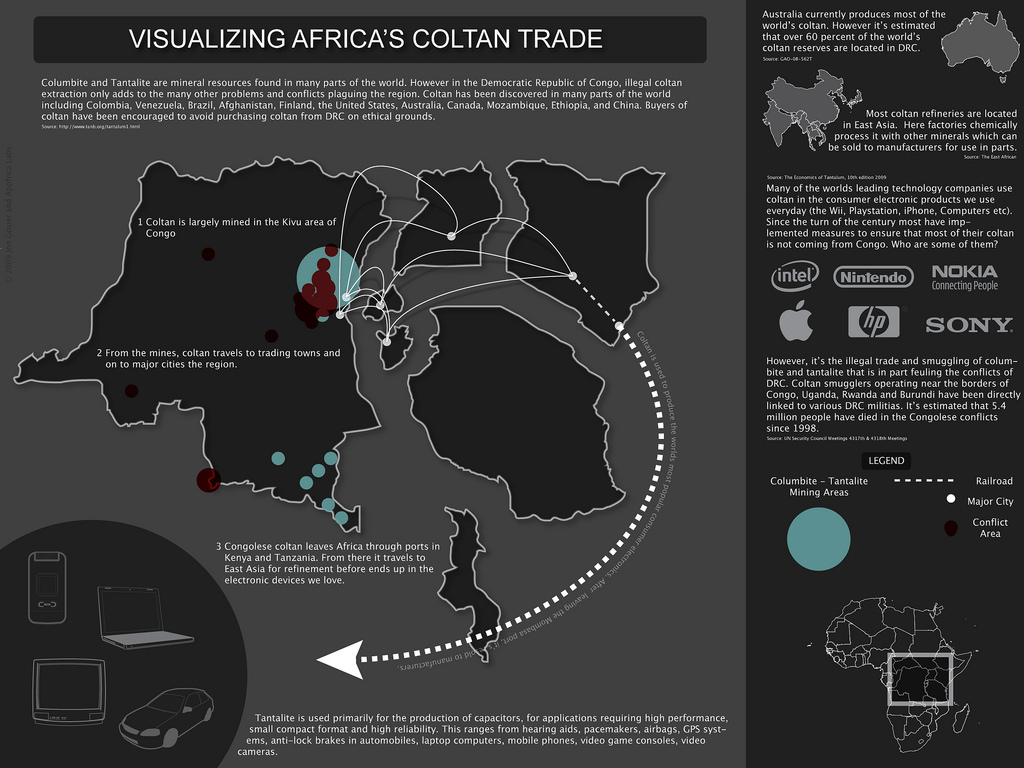

It is generally believed that resource control was not one of the motivating factors for the invasion of Zaire by Rwanda and Uganda in the first Congo war of 1996–97, but gradually the profits of mining in the eastern region became integrated in the financing of both the smaller militias and certain factions of national armies at large. This exploitation is not always systematic, but consists of small scale smuggling by rank-and-file soldiers and wildcat mining, as well as larger scale digs controlled by the Rwandan and Congolese elite.

A map of the participants in the “Great War of Africa.”

The consequences for the local populations were and are horrific. Not only does violence tear through their communities, their livelihoods are also precarious and often very dangerous. Extremely unsafe mining operations, child and forced labor, and frequent clashes over the control of mining areas are par for the course for the local populations.

Compounding the problem is that artisanal mining is often one of the only economic avenues available to local communities. This means that whenever (laudable) attempts are made at limiting the trade of conflict minerals from these areas—as for example a section of the American Frank-Dodd Act (2010) tried to do—miners and their families are inadvertently victimized again because the product they dig and sell on a small scale ends up in the commodity chains legislation is trying to restrict.

Artisan miners in Congo, including children helping their parents, in the mid-2000s.

The conflict in the eastern part of Congo has also increasingly become known in the international media for the role violence against women plays in it. Violence against women, and specifically rape, as a tactic of war is widely used by all sides of the conflict, but the problem reaches beyond the conflict itself, as the uptick of violence against women since 2008 demonstrates.

As part of the now endemic violence in the region, its perpetration is not limited to soldiers and militias and it destabilizes not just communities and families but entire populations. Likely only a minority of women report the violence, and the justice system is woefully inadequate to deal with the issue. Although it is receiving increasing attention in the global media, the focus is often on doctors and institutions instead of the women themselves.

A meeting for rape victims where women receive counseling, training, and employment from the United States Agency for International Development (left). Congolese women speaking with the International Rescue Committee’s gender-based violence program coordinator in 2010 (right).

From Kabila I to Kabila II

Although a UN peacekeeping force was approved in 1999, negotiations proceeded slowly. Not only was it difficult to bring to the table the now very fragmented landscape of militias, rebel movements, and international participants, the process was also complicated by the assassination in 2001 of L-D. Kabila by one of his bodyguards, a former child soldier.

United Nations Force Intervention Brigade in 2013 during a counteroffensive against M23 rebels.

Meanwhile, economic conditions in the DR Congo were even direr than they were by the end of Mobutu’s reign. Under L-D. Kabila, external involvement in mining and other economic sectors seems to have increased again, but much of it came in the guise of shady agreements used to satisfy allies or buy allegiances.

To the surprise of many, L-D. Kabila’s son, Joseph Kabila, emerged as his successor. At 29, the younger Kabila seemed inexperienced and aloof, but the international community met the early part of his tenure with cautious enthusiasm.

He was willing to come to the table, and in 2002, signed an agreement that aimed to end the conflict and initiate a period of transition to democracy that resulted in the 2006 elections. Declared free and fair by international and national observers, the 2006 elections raised hopes about the political future of the country.

Joseph Kabila eked out a victory and was reelected for a second and final term in 2011, in an election widely seen as much less free and fair. Kabila, whose family has roots in the eastern part of the Congo, but who did not grow up in the country, continues to be seen as an outsider, although he retains some support in parts of the east.

President George W. Bush meeting with President Joseph Kabila in 2007 (left). International observers and UN Peace Keepers in Congo for the 2011 elections (right).

Despite the hope of the transitional period, it seems that many of the current issues the country is facing have roots in the shift to democratic government. Although no longer an official international conflict zone, conflict simmered and continued to flare up, fueled by both low- and high-level interest in the country’s resources. Violence, intimidation, and abuse of the population have become anchored in the very structures of life in Eastern Congo.

Although the East is an extreme example, high-level exploitation and the continuation of a political system geared toward facilitating this exploitation and profit from it still have the country in an iron grip. Compounded by unclear and contradictory laws and opaque procedures aimed at discouraging citizen engagement, high-level mining deals such as the large infrastructure-for-minerals deal with China continue. Stories about the family fortunes of those in power or about disappearing profits from state coffers and enterprises surface with alarming frequency.

One of President Mobutu’s palaces in disrepair after being ransacked (left). Artisanal miners at a Tantalum mine in Congo featured in a 2015 U.S. Government Accountability Office report detailing that most companies were unable to determine the source for their conflict minerals (right).

In December 2016, the deadline for new elections passed. This followed failed attempts by the Kabila regime to change the constitution to allow him to run for a third term, a tactic that has proven successful for neighboring Rwanda’s Paul Kagame and Burundi’s Pierre Nkurunziza.

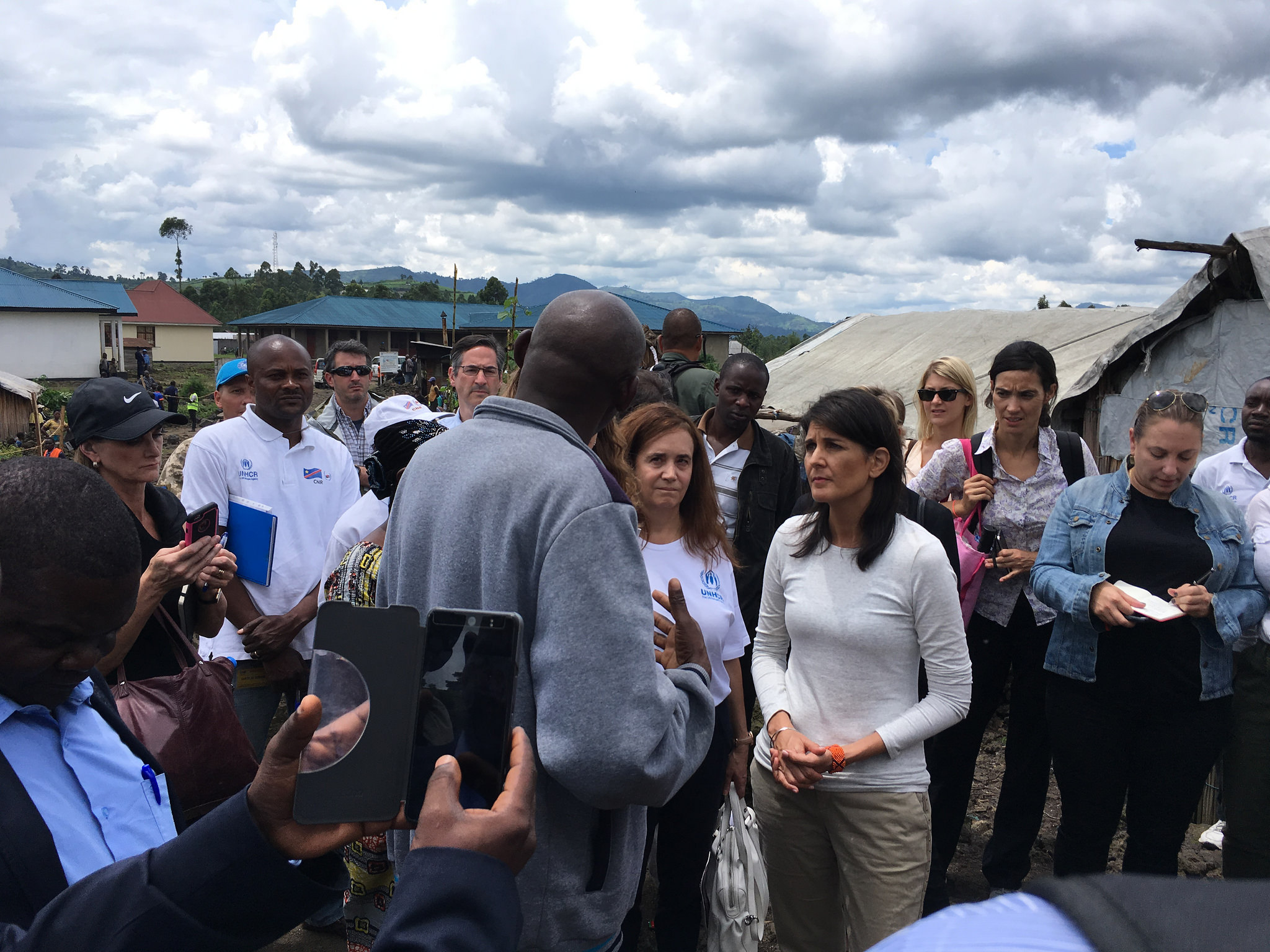

The Catholic Church, traditionally an influential segment of society, brokered a failed deal between the regime and the opposition. Recently, after a visit by the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, Nikki Haley, the government announced a new deadline of December 2018 for elections, a full two years after the president’s mandate expired.

U.S. Ambassador to the UN Nikki Haley visiting Congo in 2017.

The political opposition sees these objections as mere delay tactics, and few have much faith in the newly announced deadline. A longstanding Congolese practice that dates to the Mobutu years is to neutralize opposition through their cooptation or integration into the political—and hence economic—system. They create division and strife or endless dialogues that give the appearance of consultation. All of these further encourage the abuse of political power for personal enrichment.

Meanwhile resistance against the current regime, but also against the system at large, is rising and follows old patterns of resistance against abuses of power in Congo. Students and young professionals, who took a leading role in internal opposition to the Mobutu regime in the 1990s, are again at the forefront of protests. Aside from the capital Kinshasa, the eastern city of Goma is emerging as a stronghold of civil society and student movements.

A 2009 infographic suggesting a link between heavily mined areas and conflict regions in Congo.

At the same time, armed rebels and religious cults are increasingly destabilizing rural areas. The motivations of and culprits behind these groups are not always clear, and explanations range from the assertion of power by local and regional traditional leaders to behind-the-scenes orchestration of the current military and political apparatus.

Certainly the destabilization of the country is fast spreading beyond the Eastern region. A violent conflict with the Kamwina Nsapu group has led to an estimated 3,000 dead (including two UN observers), 1.4 million refugees (some of whom are flowing into neighboring Angola), and a looming humanitarian crisis in the Kasai region, between the capital Kinshasa in the West and the mining capital of Lubumbashi in the East.

A camp for Congolese refugees in Rwanda in 2012.

Even if elections take place in 2018, they are unlikely to bring fundamental change to the Congo. Seeing the current ruling elite as the sole villain in this story would simply legitimize its replacement with another and ignore the structural origins of the current situation. As this brief overview demonstrated, these can be traced back through the postcolonial authoritarianism of the Mobutu era to the system of colonial exploitation.

What is more, the moral righteousness with which the West often approaches the problems in the DRC conveniently overlooks the global contours of its economic exploitation. In reality, a deep restructuring of the political and economic systems is necessary, changes that are likely not possible on merely a national level but would require the participation of Western nations as well.

Read these fascinating Origins articles for more on Africa: Understanding Boko Haram; Islamist Groups in Egypt; Africa and China; Ethiopia and Nile River Tensions; Politics in Senegal; the Darfur Conflict; Piracy in Somalia; Violence and Politics in Kenya; Women in Zimbabwe; and Sport in South Africa.

Listen to this podcast: Sub-Saharan Africa.

Chris Berwouts, Congo’s Violent Peace. Conflict and Struggle Since the Great African War. Zed Books, London, 2017.

Ch. Didier Gondola, The History of Congo. Greenwood Press, Westport, CT, 2002.

René Lemarchand, The Dynamics of Violence in Central Africa. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, 2009.

Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja, The Congo From Leopold to Kabila. A People’s History. Zeb Books, London, 2002.

Theodore Trefon, Congo Masquerade. The Political Culture of Aid Inefficiency and Reform Failure. Zed Books, London, 2011.

Jason K. Stearns, Dancing in the Glory of Monsters. The Collapse of the Congo and the Great War of Africa. Public Affairs, New York 2011.

Marie Béatrice Umutesi, Surviving the Slaugher. The Ordeal of a Rwandan refugee in Zaire. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, 2004.

Congo Research Group at New York University: http://congoresearchgroup.org