When Donald Trump withdrew American military support for our Kurdish allies in Syria he not only abandoned a vital ally but, as historian Janet Klein explains this month, he fundamentally misunderstood the history of the Kurdish people. Far from being an ethnic group locked into a centuries-long squabble with Turks, the Kurds find themselves in their current precarious situation as the result of more recent historical developments. As nations formed after World War I and maps were re-drawn after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the Kurds found themselves a people without a state.

President Donald Trump justified his sudden withdrawal of U.S. military support for the Kurds in northern Syria in October 2019 with an astonishing display of ignorance and callousness. He dismissed objections to abandoning them by stating that the Turks and Kurds had been fighting for hundreds of years; and he suggested that the Kurds would be just fine because they had a lot of sand to play with.

Trump does not understand the history of the Kurds and Turks. Far from being mired in an age-old conflict, the marginal position of the Kurds today developed only recently, in the post-World War I era. It isn’t rooted in ancient ethnic hatreds, but in modern ideas of nationalism as they emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

And this history matters. Solving the uncertain fate of the Kurds and finding a resolution to today’s regional violence depend on us getting the past right.

Who are the Kurds?

The Kurds are one of the largest ethno-linguistic groups in the Middle East, with a population of some 35-40 million people centered in southeastern Turkey, western Iran, northern Iraq, and northeastern Syria and diasporic populations extending far beyond these regions.

A 2002 Central Intelligence Agency map of Kurdish populated areas in the Middle East.

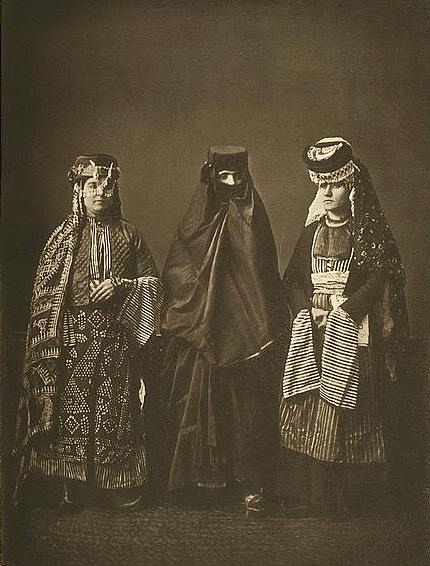

Largely Sunni Muslims with tribal kinship ties, Kurds speak one of several dialects of Kurdish, which is an Indo-Iranian language and related to Persian.

In the largely mountainous region that comprises their homeland, over the centuries Kurds practiced agriculture and animal husbandry. Until the late 19th century, many Kurds were nomadic or semi-nomadic, traveling with their flocks between summer and winter pastures and forging symbiotic relationships with settled communities. Others lived in cities and contributed to local urban culture.

Historic Kurdistan has long been a diverse region, religiously (including Jews, Christians, and Muslims) and ethnically (Armenians, Assyrians, Turks, Arabs, and others).

The Kurds within the Ottoman Empire

Much of Kurdistan was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire, centered in what is now Turkey, in the 16th century at the height of Ottoman territorial expansion.

Certain influential Kurds negotiated the terms of their integration with the imperial power such that the regions where Kurds lived tended to enjoy significant autonomy. In exchange for loyalty to the Ottoman state, these Kurdish leaders were largely exempt from taxation.

The relationship of the Kurds to the central Ottoman government and the level of autonomy that Kurdish-inhabited regions enjoyed shifted over time. Overall, however, the arrangement was mutually beneficial. The Ottomans could be assured at least nominal rule over this important frontier zone with Iran and Kurdish rulers could operate under broad conditions of self-rule.

This flexible understanding that served both sides for centuries changed markedly in the middle of the 19th century, when the central Ottoman government embarked on a series of modernizing and centralizing reforms, some of which were intended to counter the rise of competing nationalisms in the empire.

The state sought to tighten its control in the borderlands and to stave off further territorial shrinkage, having lost its territories in the Caucasus and much of its European land.

There was growing Muslim resentment against Christian groups, whom Ottoman officials believed were interested in pursuing separatist movements or reaching out to Russia or Western European countries for assistance.

The Kurds, living in an important borderland region on the eastern frontier with Persia and Russia, experienced a dramatic transformation in their longstanding relationship with the Ottoman state.

The central Ottoman government worked to eliminate the local Kurdish dynasties, including the largest and most significant—that overseen by Mir Bedir Khan (or Bedir Khan Beg). This local dynast had been modernizing and centralizing his own regional rule and exhibiting more independence than state officials had bargained for.

A 19th century watercolor painting of Bedir Khan Beg, Chief of Jezirah.

Mir Bedir Khan refused to send troops during the Ottoman war with Russia (1828-29), and by the 1840s the Ottoman military brought down his emirate. The flexible governance that had served the Ottomans well for centuries would become less accommodating, with consequences for the region’s inhabitants and the empire as a whole.

While the Ottomans had eliminated the autonomous Kurdish emirates, they did not have the state capacity to govern these regions directly. Regional Kurdish tribes filled the power vacuum and tribal leaders became the new intermediaries.

But as the Kurdish emirs before them had done, they were also able to negotiate benefits for their tribes in exchange for loyalty to the Ottoman state, which remained intent on finding local intermediaries through whom they could rule. Before the late 19th century, Ottoman authorities were not too concerned with the ethno-linguistic identity of their subject groups as long as they remained peaceful and paid their taxes.

The Hoşap castle in Van Province, eastern Turkey, in 2009. (Photo by author.)

Kurds Get Caught Up in “The Armenian Question”

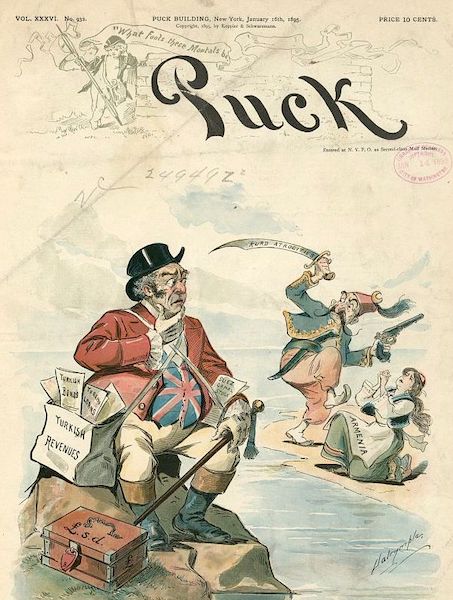

While Ottoman officials made bargains with local (often tribal) leaders in the Arab lands and even in Albania, it was particularly important for them to reach an arrangement with Kurdish leaders because of the emerging “Armenian question”—what Ottoman leaders saw as a conspiracy to sever the Armenian lands from the empire, championed by Armenian revolutionaries in collusion with Russia and Western European powers.

This “Armenian question” became a pressing concern after the Treaty of Berlin (1878) that followed the Russo-Ottoman War and envisioned the eastern part of the Anatolian peninsula as six Armenian provinces to be overseen by Russian and European powers. The Ottomans regarded it as a breach of sovereignty and a threat to territorial integrity.

An 1881 interpretive painting of the Congress of Berlin by Anton von Werner.

Kurds and Armenians lived in the same eastern borderlands, which they had shared relatively peacefully but which were increasingly contested. Due to the proximity of Kurdistan/Armenia to Russia, and as a result of Western European and Russian interest in the Armenian question, some Kurdish tribes were better positioned to strike such deals with the central Ottoman government than were tribal leaders in other parts of the empire.

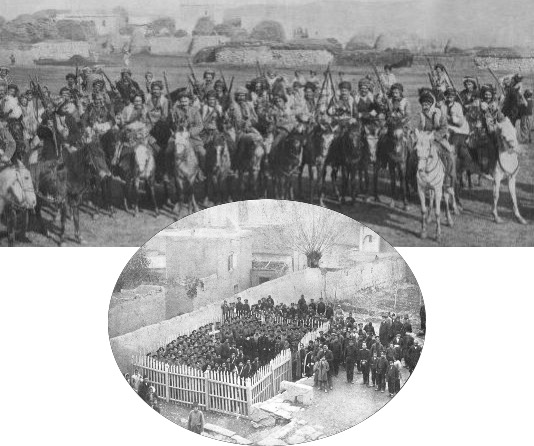

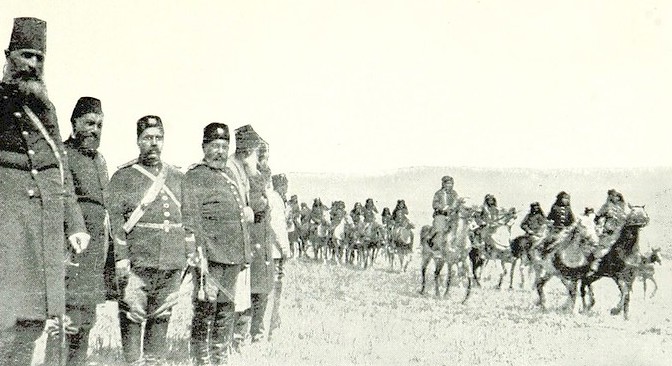

Sultan Abdülhamid II and his closest military commander in eastern Anatolia, Zeki Pasha, decided to commission select Kurdish tribes to police the eastern borderlands against the Armenian “threat.”

Taking full advantage of their commissions, these Kurdish tribes grew powerful, appropriating the land and resources of neighboring Armenians and less powerful Kurds while the sultan’s agents looked the other way. Their impunity caused widespread discontent across the region.

Protests against the sultan’s Kurdish tribal militia (called the Hamidiye) were connected to the larger movement to restore the Ottoman constitution and parliament, which Sultan Abdülhamid II had dissolved in 1878, and to overthrow the sultan himself. The Young Turk movement, as this effort came to be known, included ethnic and religious groups from across the empire.

There were Turks and Kurds on both sides of this struggle. Those who owed their power and privilege to the sultan were anxious to preserve his rule, while those who supported administrative decentralization and constitutional government sought regime change.

Each “side” was interested in preserving the territorial integrity of what remained of the shrinking empire, but embraced different tactics.

The governor of Van Province, Bahri Pasha, reviews the Kurdish cavalry in 1894.

The sultan preferred more of a police-state approach to suppress communities he believed to be working with Europeans to threaten Ottoman territorial integrity and sovereignty (as he perceived the Armenians to be doing), while the opposition believed that constitutional guarantees for all Ottomans should be secured.

Separatist activity among Armenians was far lower than the state and many Muslims perceived it to be; and it was always more a case of outside powers reaching in than of Christian groups reaching out. Yet the fear of territorial loss and European meddling was very real. Christians and Jews stood with Muslims (Turks and Kurds included) in supporting the revolutionary movement, as all believed they would benefit from a strong and diverse empire governed by the rule of law.

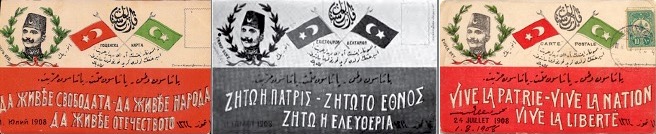

In 1908, this diverse opposition movement celebrated success in forcing the sultan to reinstate the constitution, rejoicing when the sultan himself was overthrown the following year.

There was widespread hope that the new order would bring peace and stability to communities that had suffered under the sultan’s policies, which empowered certain groups to profit from the downfall of others in exchange for personal loyalty to the sultan. They expected that more equality and the rule of law would stabilize relationships among diverse communities, thus forestalling European intervention.

World War I and a New Turkish Nationalism

However, within a few years a more Turkish-nationalist and authoritarian wing of the Ottoman Committee of Union and Progress—CUP, the main Young Turk party—came to power. After the wars in the Balkans removed significantly more territory from the empire, the CUP worked to suppress any group whose platform or activities were deemed to threaten the empire—particularly those followed by non-Turkish groups.

The CUP eventually led the Ottomans into the First World War on the side of the Central Powers, bringing a new era in “Turkish-Kurdish” relations.

“Long live the fatherland, long live the nation, long live liberty,” is declared in Ottoman Turkish and Bulgarian (left), Greek (center), and French (right) on three separate postcards from 1908 that commemorated the Young Turk Revolution.

During the war, and even briefly in the aftermath, most Kurds preferred to work with their Turkish compatriots to keep what was left of the empire intact, albeit with some level of local autonomy. After all, Mustafa Kemal—an Ottoman war hero who led the movement for independence and would become independent Turkey’s first president—himself had courted the Kurds in his efforts, offering an inclusive vision of the future state.

A multicultural state had been the goal of many educated Kurds in the late Ottoman period. They were not separatists but wanted administrative autonomy and the right and ability to develop culturally and educationally as Kurds.

However, as Turkish nationalist thought and policies spread among Turkish intellectuals and officials at the same time, Kurds began to be excluded from the process that was creating a new Turkish national identity. Despite earlier promises of equal rights in the new republic, Turkish nationalists now dismissed Kurds as backwards, barbaric, and in need of civilizing. This vision of a new, modern Turkey did not have space for Kurds as their own people on equal terms.

Built in c.750, the Pira Delal bridge crosses over the Khabur river in Zakho, Iraqi Kurdistan. (Photo by author.)

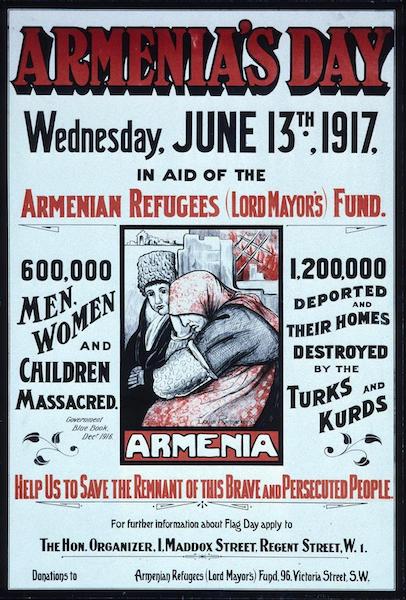

The First World War and its aftermath brought an end to the Ottoman Empire. Most of the Arab lands were lost, the Armenian population was destroyed during the genocidal massacres and deportations that targeted them (along with other Christian groups) during the war, and the two main groups who remained within the shrunken empire were Turks and Kurds.

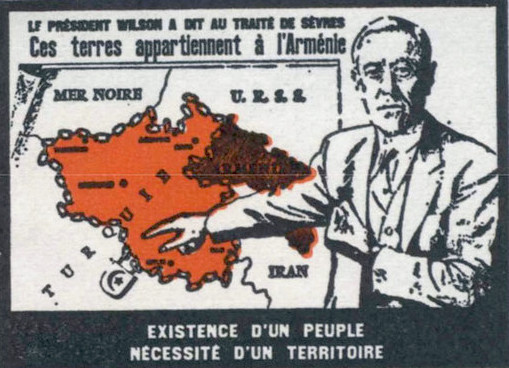

As the war concluded, different groups of Kurds hedged their bets. Some, having seen the dangers Turkish nationalism posed, read the 12th point of Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points as support for their independence.

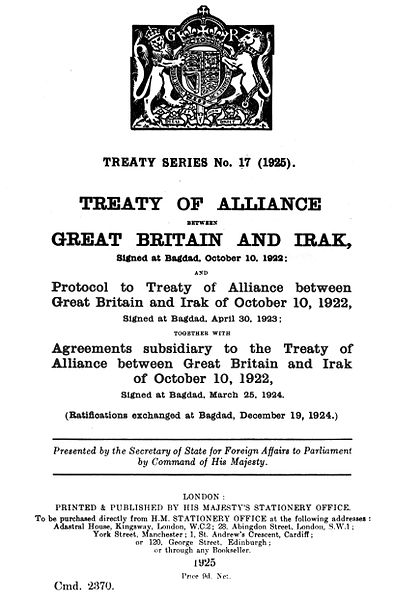

Indeed, the Treaty of Sèvres—one of a series of peace treaties at the end of the First World War—did map out an independent Kurdish state. But a self-governing Kurdistan did not materialize because post-war events took a different turn. Turkish nationalists fought to keep eastern Anatolia in what became independent Turkey in 1923 and the British opted to incorporate the Mosul Province into their Iraq mandate.

Ottoman Kurds thus found themselves divided into three new nations. In none of them were they able to exert much political power.

Minorities in the Turkish context were only recognized as such if they were non-Muslim. Kurds, therefore, were never designated as minorities with rights and protections in the post-war treaties concerning Turkey because they were largely Muslim.

After the genocidal extermination of Armenians and other Christians during the war, there were few legal minorities left in the new Turkish Republic, most Christians having been killed or deported and Jews amounting to a small percentage of the population before and after the war. In fact, Kurds did not consider themselves to be minorities.

A 1917 British poster announcing a rally and seeking donations for displaced Armenians.

While they were not formally or legally recognized as a minority either by international treaties or in official parlance in Turkey, the official line in Turkey was to deny their existence as Kurds.

Although some Kurds had fought with the Kemalists, soon after the foundation of the Turkish Republic, the state embarked on a widespread campaign to suppress and erase Kurdish identity. They engaged in population transfers to dilute the Kurdish population and violently suppressed Kurdish leaders.

The current conflict finds its roots in this era, not in earlier centuries, much less in the age-old wisps of time, as Trump more recently seemed to claim when he said that the situation had been thousands of years in the making.

Iraqi Kurdistan celebrated the Kurdish horse in 2011 with four statues. (Photo by author.)

It was in this era that conflicts between Turks and Kurds and Arabs and Kurds as such locate their origins. It was in the 20th century that the nationalist state-building policies in Turkey, Iraq, and Syria (and also Iran) led to the marginalization of the Kurds in all of these states.

The Post-war Order

After the First World War, the idea that each “people” should have its “own” state gained currency. The post-war treaties reordered the map of the Middle East, paying lip service to this idea.

Thus the colonial takeover of many Arab lands in the Middle East by Britain and France had to be framed such that these powers were not engaging in colonial domination but merely were overseeing the development of these nations until they were ready to rule themselves.

The “mandates” of Iraq and Syria are particularly important to this story, as they included significant populations of Kurds, who, despite promises outlined in the Treaty of Sèvres, did not end up with their “own” state.

As Western powers remapped the entire region, Kurds were further divided, and came to see themselves as a nation without a state. Turkey, which emerged independent and thus escaped mandate-hood, incorporated more than half of the Kurdish population within its new borders.

In all states, however, Kurds were violently oppressed and marginalized by the nationalist identities and practices of these states—as they continue to be.

Britain and France exerted colonial control over their mandates, including Iraq and Syria, even though these were not technically colonies. Under this system, political organizations in Iraq and Syria did not obtain a broad-based constituency and social groups were not able to engage with the state.

Thus, when the colonial state officially ended—Iraq in 1932 and Syria in 1946—the new states were up for grabs politically and power came to those who controlled the military. Loyalty to the regime rather than competence in governance became the most important political asset.

At the same time, both Syrian and Iraqi state officials were working out what it meant to be “Syrian” or “Iraqi.” In order to legitimate the new nation-state identities, officials in charge needed to clarify what it meant to be Syrian or Iraqi.

Some advocates of national identities continued to include all of the people within the new nation-state borders, but in both Syria and Iraq, Arab nationalism emerged as the more powerful force because Arab nationalists were best positioned strategically and historically to step into leadership roles.

In Turkey, the situation was similar to that of the mandates and vastly different at the same time. Turkey was not one of the European-created mandates and thus escaped neocolonial domination by Britain and France, but its new leader, Mustafa Kemal (later known as Atatürk), came to embrace much of what the traditional colonial powers were offering in terms of identity politics.

Turkey had emerged independent in 1923. Its leadership did see independence as an opportunity to create a unitary nation-state identity—that of Turkishness. Although Turkey emerged as Turkish, it has suppressed its other main component—Kurdishness.

Featuring Mustafa Kemal Atatürk on the 1923 cover, Time magazine’s cover reads, “Where is a Turk his own master?” (left). Turkish workers carrying the bronze head of an Atatürk statue in 1933 (right).

The “Kurdish Question” in the 20th Century

In all countries where Kurds form a significant part of the population, the “Kurdish Question” has caused state actors to fear Kurdish assertions of identity as a threat to the territorial integrity of each state.

Most Kurds in these states engaged in peaceful movements for real democracy, equality, and recognition of Kurdish cultural rights. However, the fear of Kurdish separatism has led state officials to engage in widespread repression of the Kurds, who eventually responded with targeted violence against state institutions.

In all states—perhaps especially Turkey—state authorities and their supporters see Kurdish aspirations as part of an imperialist divide-and-rule plot.

For decades in Turkey, Kurdish activists were forced to carry on their struggle for equality underground or from exile. In the 1960s Kurds engaged more openly in leftist politics and frequently joined non-Kurdish citizens in movements for social and economic justice. The military ultimatum of 1971 and coup of 1980 were largely responses to Kurdish and wider leftist activities.

It is against this backdrop that the PKK, or Kurdistan Workers’ Party, was founded in 1978 and began its armed campaign against the state in 1984. In a wider crackdown on not just the PKK but Kurdish society at large, some 40,000 people died and thousands of villages were destroyed, leaving many Kurds internally displaced.

The 1990s brought the “Kurdish Question” into the open in Turkey while brutal repression continued. In the early 21st century, Turkey appeared to make space for Kurdish political parties to operate openly, and for Kurds to press for more cultural and educational rights, among other unprecedented opportunities.

The past decade, however, has seen a reversal of this shift in Turkey, with growing repression against elected Kurdish officials, academics, and others involved in the pursuit of Kurdish rights.

In 1970, the parliament of the Kurdistan Autonomous Region was established in Erbil, Iraq.

In Iraq, the Kurds found increasing opportunities for independence following the Gulf War that began in 1991, particularly after the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003.

The Kurdistan Region remains linked to the Iraqi state, but enjoys significant autonomy, which is recognized in the Iraqi Constitution. Although Turkey has been opposed to Kurdish autonomy of any kind, Turkish contractors, developers, and manufacturers found that they were making grand profits off of the reconstruction of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. The flow of money to Turkey aided in shifting the government’s position on Iraqi Kurds’ steps towards semi-independence.

In Syria, the YPG (or Kurdish Protection Units) and YPJ (the women’s wing of the YPG) have been instrumental in resisting ISIS. They had—until the recent and abrupt withdrawal of U.S. forces from the region—carved out an autonomous zone in northeastern Syria, which some consider to be a radical anarchist, secularist project striving for gender equality.

Created in 2013, Women’s Protection Units or Women’s Defense Units (YPJ) are an all-female Kurdish militia actively fighting in Northern Syria (left). Formally established in 2011, the People’s Protection Units or People’s Defense Units (YPG) are a mixed-sex militia consisting primarily of ethnic Kurds (right).

This level of autonomy was an affront to Turkey, which feared that the Syrian Kurdish party would cross into Turkey. In early 2018, Turkish forces invaded Afrin, which many now consider a Turkish colonial outpost in Syria. Promptly after the withdrawal of U.S. forces, Turkey extended its influence in Syria far beyond Afrin.

The Meaning of Kurdistan

What is at stake here is our vision of community—who constitutes “us” and who constitutes “them,” and how we make meaning of those distinctions. This question has been key in states where Kurds live—Iraq, Syria, and Turkey, as well as Iran, which was never part of the Ottoman Empire.

Although Kurds were not considered minorities in the postwar treaties, Kurds have become minorities in the countries where they live. To be a minority often means to be regarded as an existential threat, particularly when that minority is transnational and forms a significant part of the population.

In the context of the countries in question, Kurds always have a hyphenated (and thus suspect) identity. To be Turkish in Turkey is normal; to be Kurdish is suspect. To be Arab in Syria or Iraq is normal; to be Kurdish is to be a potential enemy. To be Kurdish in all of these countries is to be considered a national threat.

How does this view of the Kurds relate to the current crisis on the Turkish-Syrian border?

Leaving aside the geostrategic interests of the United States, Russia, or any other outside party, what has animated the conflict from within is the Kurds’ sense of justice and the desire to live as Kurds—to speak one’s mother tongue and to be free of obstacles to “getting ahead” based on ethnic origin.

Kurds also wish to not be regarded as an existential threat to the nation. The areas in all countries that incorporated historical Kurdistan have been heavily militarized over much of the last century. When Kurds have taken up arms against the new national states they lived in, it has generally been in response to violent and repressive measures against them.

Supporters of the Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK) at a 2003 London rally opposing the Iraq War.

Turkey, in particular, has used the fact of Kurdish armed uprisings as a pretext to treat all Kurds as security threats, and to crack down on peaceful Kurdish movements for democratic rights and freedoms. As the PKK was designated an international terrorist organization, Turkey has used this designation to suppress peaceful Kurdish activities by alleging that they all have ties to terrorism.

The democratic movements and growing autonomy of Kurds in Iraq and Syria are seen as particularly menacing to Turkey, as Kurds have maintained cross-border ties and draw inspiration from movements that have achieved significant regional autonomy. An autonomous Kurdish existence anywhere, even outside of Turkey, is regarded by Turkish officials as deeply threatening.

Thus, if the current situation continues to play out as it is, the Kurds will not be “just fine,” as the U.S. president suggested.

A 2017 pro-Kurdistan independence rally in Erbil.

While the abrupt U.S. withdrawal of forces allied with Kurds in northern Syria left them open to brutal attacks by Turkish armed forces, the most important measure to protect the sanctity of life in Kurdish communities (and indeed the region at large) is to promote genuine democracy and inclusive nation-state identities that see Kurds as real citizens, and as important and equal members of the nation.

Read more on the Middle East: Turkey’s Politics; the Alawites and Syria; ISIS; Islamic Politics in Egypt; The Religious Divide in Iraq; The Sunni-Shi'i Divide; Feminism in Egypt; Yemen Civil War; U.S.-Iraq Relations; and The U.S. War in Iraq.

Listen to these History Talk podcasts on Understanding the Middle East; Yemen: Inside The Forgotten War; Women in the Mideast and North Africa; and the Syrian Civil War and Arab Spring.

Allsop, Harriet, and Wladimir van Wilgenburg (2019), The Kurds of Northern Syria: Governance, Diversity and Conflicts, London: I.B. Tauris.

Cora, Yaşar Tolga, Dzovinar Derderian, and Ali Sipahi, eds. (2016), The Ottoman East in the Nineteenth Century: Societies, Identities, and Politics, London: I.B. Tauris.

Gunes, Cengiz, and Welat Zeydanlıoğlu, eds (2014), The Kurdish Question in Turkey: New Perspectives on Violence, Representation, and Reconciliation, New York: Routledge.

Jabar, Faleh, and Renad Mansour, eds (2019) The Kurds in a Changing Middle East: History, Politics and Representation, London: I.B. Tauris.

Kieser, Hans Lukas, Kerem Öktem, and Maurus Reinkowski (eds), (2015), World War I and the End of the Ottomans: From the Balkan Wars to the Armenian Genocide, London: I.B. Tauris.

Klein, Janet (2011), The Margins of Empire: Kurdish Militias in the Ottoman Tribal Zone, Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Klein, Janet (2014), “The Minority Question: A View from History and the Kurdish Periphery,” in E. Pfoestl and W. Kymlicka (eds), Minority Rights and Multiculturalism in the Arab World, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 27-52.

Klein, Janet (2019), "Making Minorities in the Eurasian Borderlands: A Comparative Perspective from the Russian and Ottoman Empires," in K. Goff and L. Siegelbaum (eds), Empire and Belonging in the Eurasian Borderlands, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, pp. 17–31, endnotes pp. 211–16.

Leezenberg, Michiel (2016), “The Ambiguities of Democratic Autonomy: The Kurdish Movement in Turkey and Rojava,” Southeastern European and Black Sea Studies 16, pp. 671-690.

Rodrigue, Aron (1995), interviewed by Nancy Reynolds, "Difference and Tolerance in the Ottoman Empire," Stanford Humanities Review 5, pp. 81–92.

Üngör, Uğur Ümit (2011), The Making of Modern Turkey: Nation and State in Eastern Anatolia, 1913–1950, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Weitz, Eric (2008), "From the Vienna to the Paris System: International Politics and the Entangled Histories of Human Rights, Forced Deportations, and Civilizing Missions," American Historical Review 113: 5, pp. 1313–43.