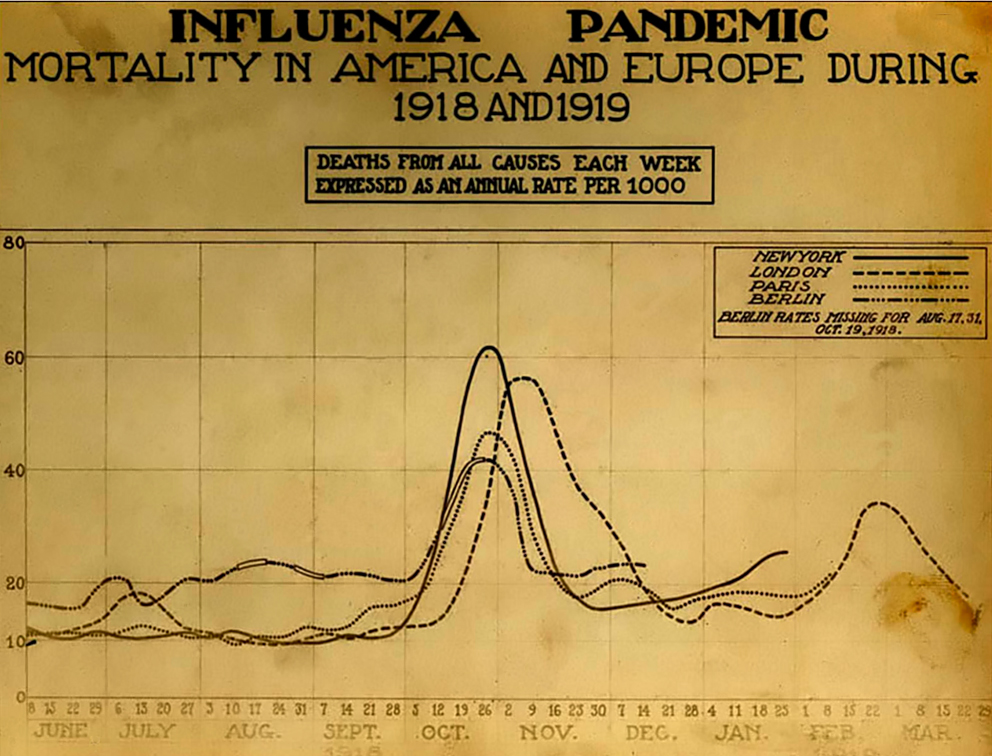

November 1918 was the deadliest month of the greatest pandemic in recorded history: the “Spanish Flu.”

Recent estimates suggest that this flu claimed as many as 50 million lives around the world between 1918 and 1919, killing more people in a single year than the entire “Black Death” of the 14th century. On its centennial anniversary, it is worth remembering the history of the “Spanish” flu and how it set us on the path towards our modern flu vaccine.

Burying victims of the Spanish Flu in Canada.

When the first cases of the influenza A (H1N1) pandemic broke out in 1918 during the final year of World War I, the origins of this deadly pandemic were unknown. Contemporary explanations in the Allied nations ranged from fears of a new form of biological warfare to a by-product of trench warfare resulting from the use of mustard gas.

The Spanish “origin” relates to reports in the press of cases of influenza in the summer of 1918, where as many as eight million Spaniards succumbed to the disease. Even the King of Spain, Alfonso XIII, caught influenza in 1918.

King Alfonso XIII of Spain (r. 1886-1931)

The standard narrative maintains that the first cases broke out in a military camp in Kansas where few noticed the signs of the pandemic to come amid the ongoing war. On March 4, 1918 company cook Albert Gitchell, possibly patient zero, reported sick with a fever of 104º Fahrenheit at Camp Funston, part of Fort Riley, where 54,000 men were gathered for basic training. Within days, 522 soldiers reported sick and by the end of the month 1,100 soldiers were admitted to hospital with influenza.

The wartime context for the pandemic is especially important: not only did the flu claim more lives than the war itself and prolong the suffering brought about by the First World War, but the pandemic also followed the movement of soldiers around the globe. The American Expeditionary Forces (AEF), which deployed out of Kansas to France, were likely carrying the flu with them in the spring of 1918 as the Allies rushed deployments to halt the German Ludendorff Offensive. The first British cases occurred in mid-April as well, spreading out of ports and Scottish dockyards.

Still, little attention was paid to what contemporary physicians described as a “three-day fever” circulating in Europe in late spring and early summer 1918.

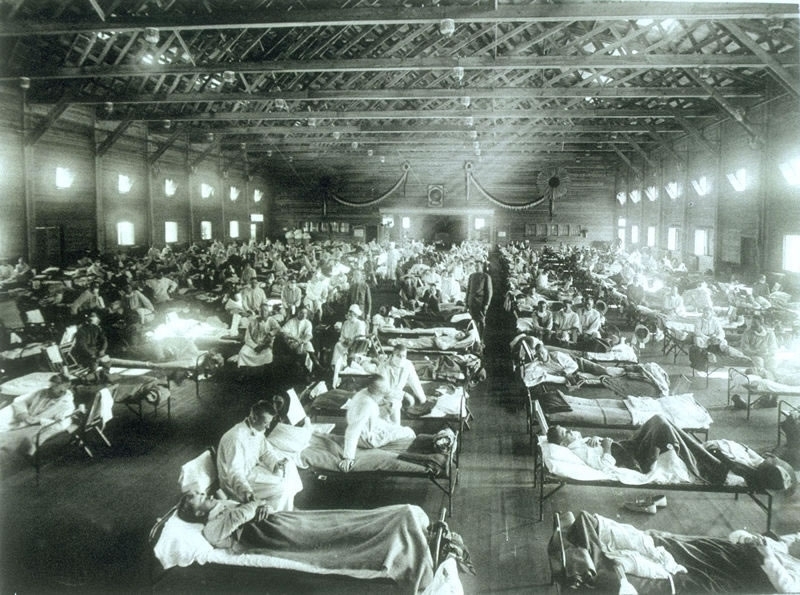

An influenza hospital at Camp Funston.

In this first phase of the pandemic most patients recovered quickly; their fevers broke after two days and most were fit for work within a week. Only a minority of patients suffered complications (pneumonia) that led to fatalities. Moreover, by June 1918 the number of cases in Europe and North America began to steadily decline leading to a belief that the flu pandemic was over.

In late August, however, the flu reemerged suddenly across the globe and with much greater lethality.

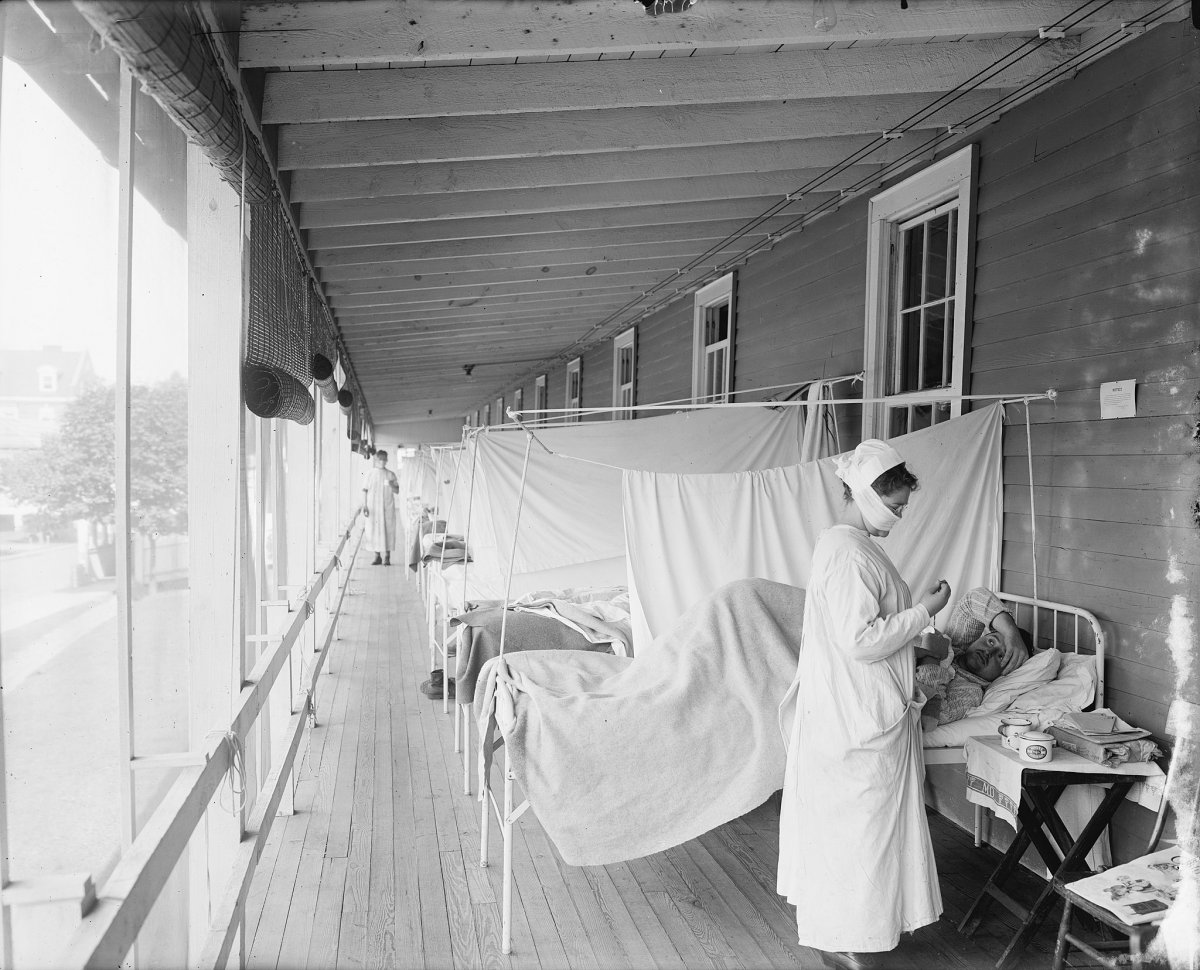

The Spanish Flu ward at Walter Reed Hospital.

This second phase of the pandemic began almost simultaneously in Brest (August 22), Freetown (August 24) and Boston (August 27)—all major military port cities. Over the course of the next four months, flu circled the globe infecting approximately 500 million people. Hospitals were overwhelmed. Doctors and nurses disproportionately fell victim to the pandemic while treating an unprecedented number of patient-cases. Pulmonary complications appeared more frequently, contributing to a mortality rate twenty-five times higher than a normal influenza outbreak. Fatalities peaked in November 1918.

Military officials were often the first to realize the severity of the flu, but they did not understand the nature of the illness. The Royal Army Medical Corps began bacteriological examinations of soldiers for “Pfeiffer’s bacillus” (Bacillus influenzae), which was incorrectly identified as the causal microbe responsible for the flu in 1892 by the German physician and bacteriologist Richard Pfeiffer.

Spanish Flu mortality by month.

In the United States, William H. Welch, former president of the American Medical Association and a member of the Johns Hopkins Medical School, and his team studied the epidemic in military camps in September 1918, employing state-of-the-art medical research techniques to treat Pfeiffer’s bacillus. Welch and his team tried a host of antiserums, vaccines, and medical compounds—all to no avail. Their microscopes could not see something as small as a virus.

Meanwhile, civilian public health programs remained conflicted about how to respond to the pandemic.

A flu victim in St. Louis.

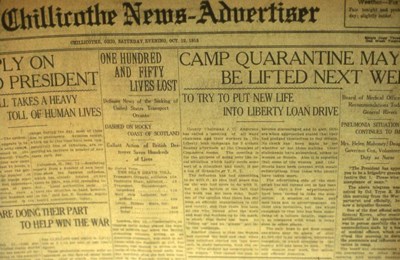

Arthur Newsholme, head of the British Local Government Board, the government organization responsible for the oversight of domestic public health campaigns, told Britons to simply “carry on.” To impose quarantines necessary to contain the pandemic would have been too detrimental to the war economy. Parliament did not impose any sort of public health legislation until November 1918, and these laws only limited the duration of public gatherings and access to cinemas.

In the United States, the American Public Health Association (APHA) was more proactive in its efforts to prevent the spread of the flu and reduce the severity of the pandemic. The APHA recognized that the disease was extremely communicable and sought to break the channels of infection. It initiated respiratory-hygiene education campaigns about the dangers of coughing, sneezing, and the careless disposal of nasal discharge.

An Ohio newspaper informing residents about the current status of a quarantine (National Park Service).

The gauze mask was another important preventive tool. The face masks consisted of a half yard of gauze, folded like a triangular bandage covering the mouth, nose, and chin. Some cities, like San Francisco, legislated that everyone should wear a gauze mask in public. A popular rhyme was created to remind people of the city ordinance:

Obey the laws

And wear the gauze

Protect your jaws

From Septic Paws

Ultimately, very little succeeded to effectively control the pandemic. By winter 1918, the pandemic suddenly dropped off, although a third, final, and milder phase would resurge in the spring of 1919. It too passed naturally.

Physicians and medical researchers could ultimately do little about the flu’s onslaught. For years physicians wanted to quietly forget their inability to combat the pandemic. Yet, the 1918 global influenza pandemic left an important legacy in the history of medicine.

Beyond shocking tolls, the pandemic inspired a surge in biomedical research.

In 1919, doctors attempted to vaccinate patients against influenza, developing a vaccine for Pfeiffer’s bacillus that proved completely ineffective. After the pandemic had passed, biomedical researchers began to reevaluate the etiology of influenza with the goal of preventing a future pandemic. Between 1935 and the early 1960s the influenza virus was the most studied virus infecting humans. In 1936, H1N1, the strain of the influenza responsible for the pandemic, was isolated in a laboratory beginning the path towards a vaccine, which was first tested, again in the context of war, on U.S. soldiers during World War II.

Red Cross litter carriers during the Spanish Flu outbreak in Washington, D.C.

Over a century later, we are regularly vaccinated against the H1N1 strain of influenza in our annual flu shot so that, with hope, we do not have a repeat of the 1918 pandemic. It was a human catastrophe that never should have been forgotten.