History doesn’t repeat, but to quote a phrase often attributed to Mark Twain, “it often rhymes.”

Indeed, few historical comparisons make more compelling verse than the COVID-19 outbreak and history’s greatest pandemic: the Black Death. Its impact upon Europe allows us to speculate about the aftermath of COVID-19.

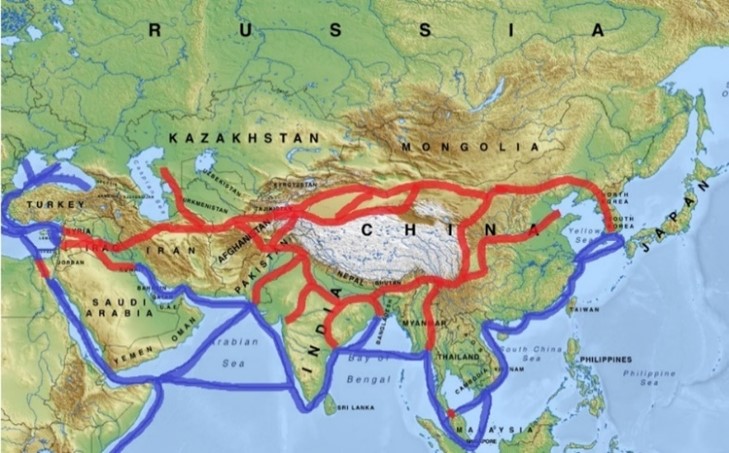

Medieval Eurasian Trade Routes, with the red lines indicating land-based trade networks and the blue indicating ocean-based routes. (Map courtesy of the author)

The Black Death needs little introduction. Caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, the plague emerged in central Asia in the 1330s, spread west along the Silk Road, and was carried by Genoese merchants from the Crimea to Europe in late 1347. Once it hit the Continent it spread 4 kilometers per day and by 1351, 50% of Europe was dead.

The Black Death was devastatingly disruptive to governments everywhere. In England, for example, analysis of Crown correspondence shows an immediate drop in business of 30% or more. Not only did the most important court in England, the London-based King’s Bench, shut down completely in 1348 but in some quarters, administration stopped operations altogether. This was caused in no small part by the deaths of many officials at all levels of government.

Undoubtedly the Black Death’s greatest impact was economic. It brought about “the greatest demand-side shock” (drastically fewer consumers) and “the greatest supply-side shock” (fewer people available to perform wage labor) in recorded history.

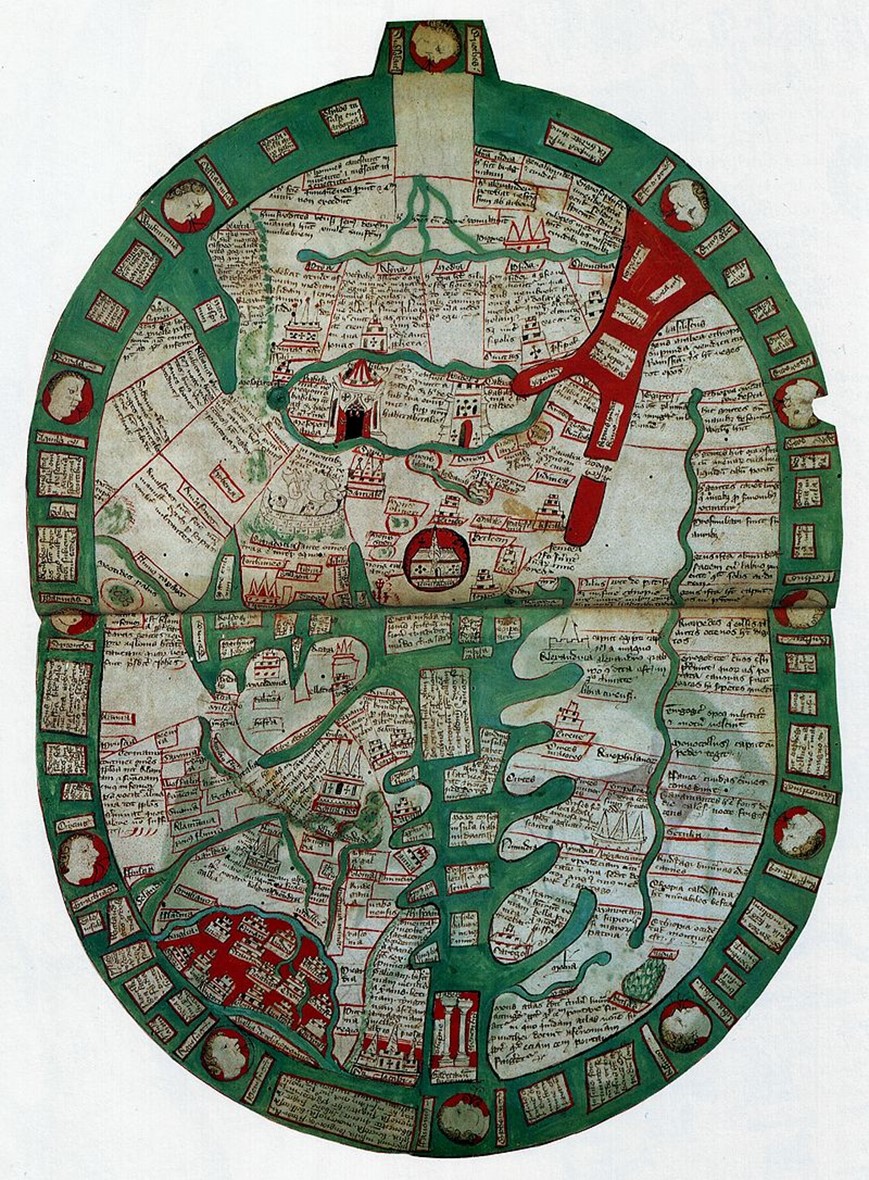

The Black Death's path across Europe between 1346 and 1353.

When the outbreak began, international trade radically decreased in volume, ceasing in some areas completely. Agricultural production halted as villages were abandoned and acres of crops went unharvested. Historians even estimate that by 1400, over 3,000 English villages and towns ceased to exist.

Prices for grains, livestock, and labor fluctuated wildly, while innumerable merchant businesses failed. Several Italian super-companies that were prominent moneylenders to the kings of Europe collapsed entirely.

By some estimates, the plague cut Europe’s GDP in half. As Ranulf Higden wrote in his chronicle Polychronicon,“…rents dwindled, land fell waste for want of the tenants who used to cultivate it, and so much misery ensued that the world will hardly be able to regain its previous condition.”

With such dark pronouncements, one might think that recovery took years, if not decades. Yet surprisingly, the panic was temporary.

Although London was gripped with plague, new officials were appointed to fill vacant positions and, by the beginning of 1349, various Crown offices began meeting in alternate locations. While the King’s Bench in the capital did cease operations, those in York and Lincoln continued to hear cases. Westminster reopened in August and by September, the English Crown was more or less operating as normal.

Researchers have also underscored the plague’s positive effects on public health. The devastation caused governments to slowly appreciate how important quarantine measures were to prevent infection.

Various Italian cities were the first to establish rules for separating the sick from the healthy, with such measures spreading to other European cities in the following decades. Indeed, many argue that plague waves between 1348 and 1415 gave rise to proto-public health and sanitation systems, which formalized beginning in the 16th century.

Economic recovery was also swift. By late 1350, commodity and labor prices stabilized. Trade resumed and new merchant companies were established to fill the gaps left by those that had failed. Because of the stark population drop, demand for wage labor increased markedly, as did the pay these workers could command. The peasantry’s net worth improved, which afforded them more economic agency than they had previously possessed.

Many then purchased land due to the high number of abandoned farms available. Others created more independent relationships with the nobility they served because lords were desperate for farmers to cultivate their fallowing manors.

Together these measures helped shift power down the social scale, signaling the final death knell of medieval feudalism.

In the end, rather than proving an enduring disaster that set those who survived back for decades, governments, economies, and people proved resilient. In fact, the Black Death era proved to be the catalyst for many monumental changes in Europe.

As historian John Aberth observed, “no longer can we afford to write off Europe at the end of the Middle Ages as a wasted society waiting for the modern era to begin. Rather, Europe’s rebirth was forged in the crucible of its terrible yet transcendent ordeal with the Black Death.”

So, if history does rhyme, what do these outcomes indicate might be the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic?

First, it seems certain that despite current divisions, our political institutions will persevere. Legal courts that were either open on a limited basis or shuttered completely will reopen. Government and legal institutions may even adopt permanently the various digital measures implemented as temporary necessities throughout 2020.

At the same time, the condition of local, national, and global economies is an acute concern. Yet, the Black Death teaches us that recovery can be swift and lasting. Should the economic trends present in January 2020 continue, both national and global resurgence is likely.

Finally, COVID-19’s impact upon public health and medicine will be significant. Methods for developing vaccines have been honed while vaccine alternatives such as monoclonal antibodies could prove effective for treating other diseases in the future.

Studies attempting to understand the body’s immune response to SARS-CoV-2 could help treat a myriad of autoimmune disorders, while the outbreak has proven the efficacy of telemedicine. Overall, healthcare outcomes seem promising, although this crisis should push governments to adopt more proactive measures to prevent (or at least minimize) similar crises in the future.

In the end, despite the many hardships that we are experiencing in these trying times, the Black Death’s aftermath suggests the possibility of constructive trends in the years to come. Some things will not change so much—COVID-19 has surely proved wrong speculation that the digital world will soon replace the tangible one—but it is very possible that many things can and will change for the better.