This is not the first time that humans have been confronted by pandemic disease. Historians have long studied these pandemics, taught their lessons, and preached to be prepared for the next one. In summer 2020, Origins has embarked on a special project to help us better understand COVID-19 by running a series of essays, podcasts, and videos putting the pandemic in historical perspective. This month, historian Jim Harris provides an overview of pandemics from the ancient world to the modern. We invite readers to learn more about coronavirus and pandemics by visiting this page and to do so regularly as we will keep adding new stories. Stay safe.

The emergence of the novel coronavirus COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) has been a grim reminder of the role that disease-causing microbes such as bacteria and viruses have played across the long span of human history, despite tremendous advances in biomedicine in recent years.

Three of our “deadly companions.” Poliovirus (left), Influenza (center), and COVID-19 (right).

Our “deadly companions,” to use Dorothy Crawford’s apt term, are presently responsible for 14 million deaths per year, and they have profoundly shaped human history and even human evolution. These microbes have assumed many forms, from plague, influenza, and HIV to cholera, smallpox, polio, and measles. And now coronavirus.

COVID-19 has—as ofJune 2, 2020, approximately six months since the pandemic began—claimed 377,460 lives around the world (though that number is surely inexact).

It has dramatically altered patterns of behavior: necessitating social and physical distancing; closing businesses, houses of worship, and schools; and forcing the cancellation of large public gatherings. All of these measures have been hard on humans as social animals who need jobs, education, and faith.

COVID-19 has brought renewed light to the impact our “deadly companions” can have—a lesson that has been largely forgotten since the deadliest outbreak to date, the global influenza pandemic of 1918.

For most of human history, our relationship with deadly microbes has been invisible. Scientists have only been able to identify specific disease-causing pathogens for the past 140 years.

German physician Robert Koch identified the first disease-causing bacteria in 1882 when he reported that Mycobacterium tuberculosis was responsible for causing tuberculosis. Two years later, he then identified another bacterium, Vibrio cholerae, which causes cholera. Viruses were not observable until the development of the electron microscope in 1931.

Despite their imperceptible nature, the impact of our “deadly companions” is clear in the historical record. And the history of pandemics helps us better appreciate the current COVID-19 experience.

It highlights for us how an increasingly global society makes us more susceptible to pandemics. It also shows how relatively recent advances in medicine have shaped our current epidemiological response, public health institutions, and global disease surveillance systems, as well as the development of vaccines, masks, and social segregation.

By studying the history of pandemics, we gain an appreciation for the economic as well as the social costs they bring to bear. History also offers an opportunity to learn from our past mistakes, such as stigmatizing patients in ways that were often as punishing as the disease itself. It reminds us to offer abundant empathy for patients suffering from COVID-19 and their families.

Pandemics in the Ancient World

Migration of large numbers of people, especially during wartime, has been a significant factor in the spread of pandemics throughout human history. In the ancient Mediterranean world, we find written accounts of three of the earliest recorded pandemics, and in all three cases military campaigns across their “world” contributed to the proliferation of the pandemic.

In the History of the Peloponnesian War, Thucydides described the sudden onset of a disease in people who were otherwise in good health: the Plague of Athens (430-426 BCE). The disease, he wrote, spread into the Greek world from across the Mediterranean in North Africa.

"Plague in an Ancient City" (1652-1654) by Michiel Sweerts depicts the epidemic that ravaged Athens.

“The disease began with a strong fever in the head and reddening and burning in the eyes; the first internal symptoms were that the throat and tongue became bloody and the breath unnatural and malodorous.” By the time it afflicted the heart, it “produced every kind of evacuation of bile known to the doctors, accompanied by great discomfort.”

While the specific disease that caused the Plague of Athens remains a mystery, this early pandemic reveals how humanity has been, historically, highly susceptible to and largely powerless to stop pandemic disease.

Amid ongoing wars with Sparta, the Athenians were forced to shelter behind their protective city walls. Confined Athenians were easy prey to the plague that swept through their overcrowded city, killing as many as 100,000, including the leader Pericles.

Pericles, an Athenian statesman who died during the Plague of Athens in 429 BCE.

The results were devastating.

Men “became indifferent to every rule of religion or law,” according to Thucydides, and the bodies of victims were often buried in mass graves. In the end, the plague of Athens may have also contributed to its eventual defeat in the Peloponnesian War, as the city did not fully recover for a generation. This, in turn, weakened Athenian influence throughout the Greek world.

As Roman soldiers returned from campaigning in 165 CE, they too brought another ancient pandemic back with them: the Antonine Plague (165-180 CE). Based on records kept by the physician Galen, we know that this pandemic, which would ultimately claim five million lives, spread throughout Italy, Greece, Egypt, and Asia Minor and was most likely an outbreak of either measles or smallpox (and if the latter, then it would be the first recorded epidemic of smallpox in Europe) .

According to Galen, the disease afflicted young and old, rich and poor, as it subjected its victims to fever and thirst, vomiting and diarrhea, and black rash. Killing between a third and half its victims, the Antonine Plague contributed to a severe decline in the population of the Roman Empire and, in turn, the onset of a period of economic and military decline in the longer history of the empire.

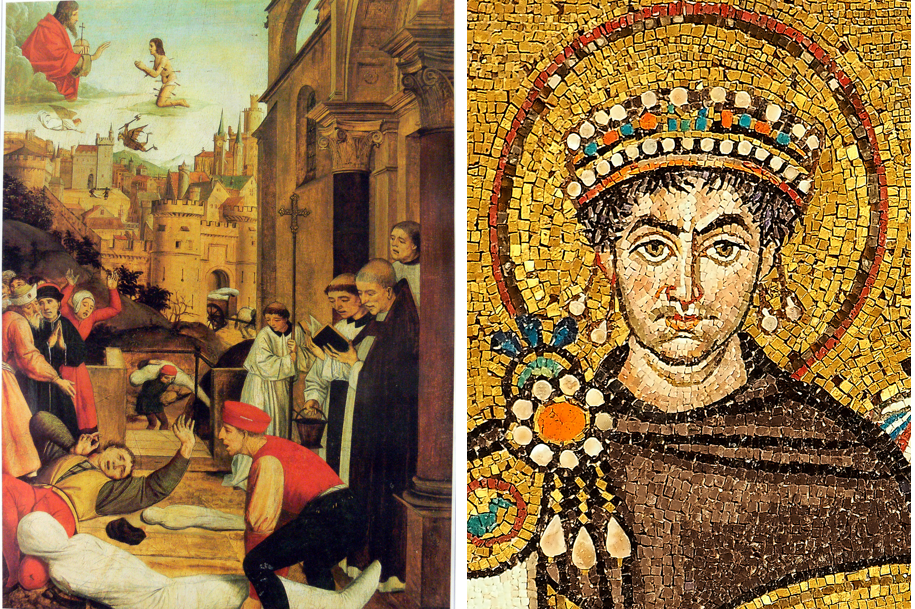

The Justinianic Plague, named after the Byzantine Emperor Justinian (r. 527-565), is perhaps the most consequential pandemic in the ancient world. It is important both for its longevity (c. 541-750 CE), but also because this was the first (of three) clearly documented pandemics of Yersinia pestis, the bacteria responsible for bubonic/pneumonic/septicemic plague.

St. Sebastian pleads with Jesus for the life of a gravedigger afflicted by the Justinianic Plague (left). A sixth-century mosaic depiction of Justinian I from San Vitale in Ravenna (right).

Until recently historians have thought this plague, which killed an estimated 30 to 50 million people across the Eastern Roman empire over the course of two centuries, brought about the end of these great ancient Roman societies. However, emerging scholarship and new data reveal that this pandemic, while certainly deadly, may not mark the “end of the [ancient] world.”

According to a recent study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, people in late antiquity adjusted to two centuries of a recurring pandemic. Economic data show relative stability through these plague centuries, as do land-use data, which suggest that despite enormous losses of life, the ancient Mediterranean world learned to live with the plague.

We face a similar challenge today.

The Black Death

In October 1347, bubonic and pneumonic plague returned to Europe by way of the port of Sicily. From 1347-1353 most of Europe suffered from the Black Death.

Estimates on the total death toll during this second plague pandemic range considerably and suggest that between 30 and 60 percent of Europe’s population died in a near cataclysmic disaster. Globally, the second plague pandemic may have claimed anywhere from 75 to 200 million lives.

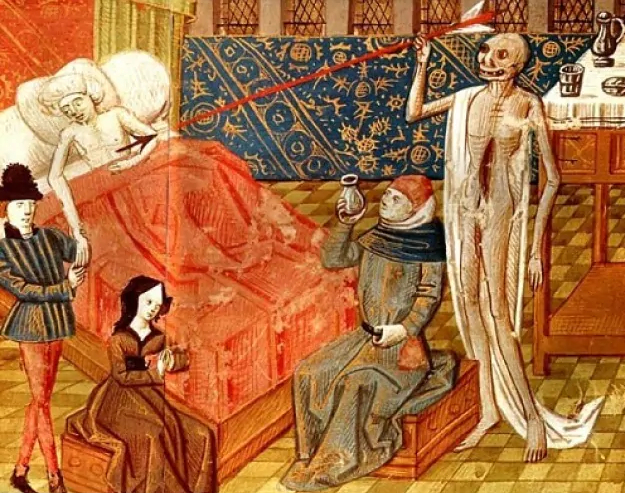

A depiction of the Black Death in a 15th-century Italian miniature.

The history of the second plague pandemic teaches us several important lessons—from the way diseases reach pandemic levels to lessons about how societies recovered from past pandemics and the earliest forms of public health.

Perhaps carried by the fleas in the fur of rodents or via human fleas or head lice, the second plague pandemic followed trade routes out of Central Asia and into Europe via the Mediterranean ports, from the isle of Sicily to the Italian peninsula in Pisa, Venice, and Genoa, and into France from the port of Marseilles.

From there, the pandemic spread indiscriminately across the continent, especially in growing European cities, inciting considerable panic as it inflicted dramatic symptoms (especially the large, painful swellings of the lymph nodes, the characteristic “buboes”) and enormous loss of life.

In The Decameron, Giovanni Boccaccio described “fathers and mothers [who] fled from their own children, even as if they no way appertained to them.” Many believed that this plague was the wrath of an angry God and marked the very end of the world.

The plague of Florence in 1348, as described in Boccaccio's Decameron. Etching by L. Sabatelli.

Jews and lepers, both groups considered outsiders in Christian society, were accused of maliciously spreading the disease. European Jews were subjected to especially cruel tortures and murder as a “prophylactic measure,” which ranged from being sealed in wine casks and rolled into the Rhine River to being burned at the stake.

Depending on regional conditions and mortality rates, the social order during the Black Death was restored more quickly in some cities than in others. Careful city governance helped. For example, in the Tuscan city of Siena, economic and political activities ceased nearly entirely in the summer of 1348, but the community rebounded rapidly, rebuilding its cloth industry after only a matter of months.

But Siena was just one part of the story. Elsewhere in Europe, the larger-scale social consequences of the massive loss of life lasted centuries. With this tremendous depopulation, the value of labor increased while the cost of land depreciated, forcing existing social hierarchies to adapt.

The Black Death accelerated the decline of feudalism in England. In the estimation of historian Dorothy Porter, plague increased “geographic mobility” and created the “basic economic conditions for free-market labor mobility.” Landowners could no longer tie workers to the land and prevent them from moving to better-paid employment elsewhere.

Elsewhere, containment of the plague required more lasting interventions, particularly the development of public-health institutions with the authority to intervene in communities to mitigate disease.

In Venice, an ad hoc committee was established to “preserve public health and avoid the corruption of the environment.” By 1348, this committee closed all ports and imposed quarantines on newly arriving ships and travelers.

The etymology of the term quarantine comes from the Italian quaranta giorni (forty days),the duration of these plague quarantines.

Other Italian and French port cities followed suit as the plague continued to ebb and flow periodically through Europe over the course of the early modern period, establishing medical commissions to eliminate “corruption in the air” that they believed to be the cause of disease.

By the 15th century, these early health commissions focused their efforts especially on monitoring early-modern mass gatherings—schools, church services, processions—for signs of plague. When outbreaks were found, strict quarantines were imposed. Special fortresses, lazarettos, were built to house plague patients.

Here we find the historical roots of tried-and-true public health measures, which are still necessarily employed today: public health commissions and enforced social isolation.

Such public health strategies are complex, and do not come without costs. Many fear the economic consequences of prolonged “stay at home” orders during the COVID-19 pandemic, and rightly so.

The economic consequences of quarantine (and the mortality rate) during the plague years were notable. Cordoning off household manufacturing had economic consequences that rippled through early-modern supply chains.

In parts of rural England, such as the village of Cuxham (near Oxford), mills fell into disuse and livestock wandered untended. Manors went unmanaged as landholders fled and laborers died.

The population of Cuxham would not recover for decades, and scholars believed that the economic recovery from the plague took even longer: until the 15th century.

Pandemics in Modern History

The history of pre-modern pandemics demonstrates the devastating demographic and social impacts that past pandemics had and the fears that invisible “deadly companions” created. The demographic threats of pandemics remain. But medical advances in the past 200 years—a relative blip in the long history of humanity and its relationship with pandemic-inducing pathogens—give us reason to be less fearful.

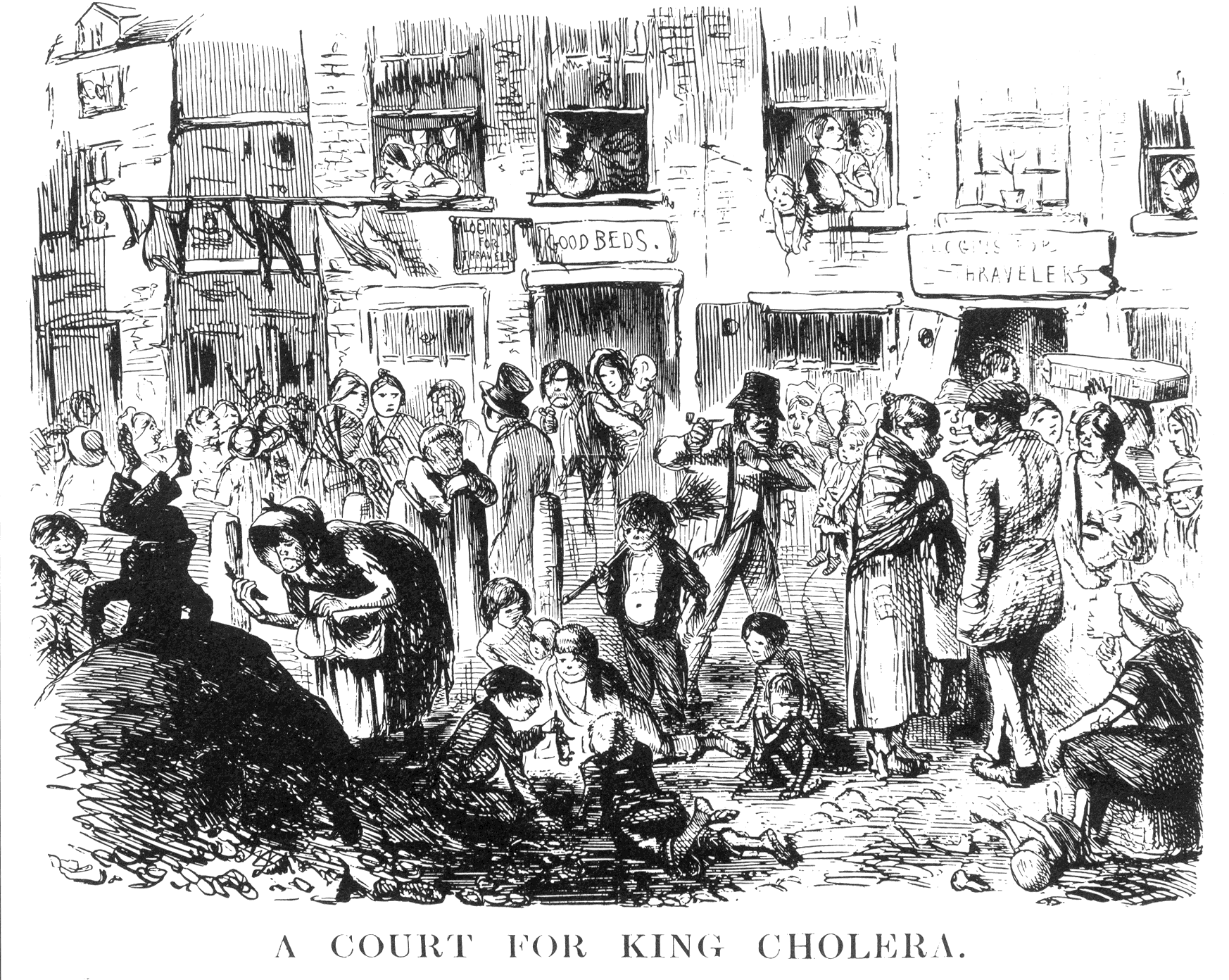

Modern epidemiology and the germ theory of disease both developed in response to not one, but six cholera pandemics over the course of the 19th century (1817-1824, 1829-1837, 1846-1860, 1863-1875, 1881-1896, 1899-1923).

This 1888 Life magazine cartoon, symbolically illustrates the threat of a cholera epidemic rising up out of the London slums, and crossing the Atlantic to threaten New York City, while “Science”, which is metaphorically depicted as a sleeping soldier on the docks, lies unaware of the impending doom (left). An 1832 engraving from J. Roze depicting the treatment of victims of the cholera epidemic in Paris (right).

During these cholera pandemics, which like plague followed trade routes out of Central Asia into Europe, the medical presumption was that a poison in the air, a mal aria (“bad air” in Italian) or “miasma,” was responsible for pandemic.

The first modern epidemiological investigation into a pandemic, however, disproved the miasma theory of disease.

During the third cholera pandemic, in 1854, Dr. John Snow observed in the Soho neighborhood of London that a single (infected) water pump was the epicenter of a ring of infections of cholera. When its handle was removed, the infections ceased. From this Snow correctly inferred that cholera was waterborne disease, not one carried in the air, although the Vibrio that caused the disease was not identified for several more decades.

Understanding the epicenters of infection, like the case of the Broad Street Pump, became a vital component of pandemic response and containment, as well as the basis for modern contact tracing.

The history of pandemic response has been far from perfect, however.

In 1889-1890, an influenza pandemic spread outward from Russia, killing approximately a million people around the globe. Comparatively, this pandemic was small in mortality, but its rapid spread across the northern hemisphere in less than four months revealed how susceptible the world was to a major pandemic because of new travel technologies (especially railways and steamships).

More significantly, during the Russian flu pandemic, German physician Richard Pfeiffer began to take samples of nasal discharge from his patients and ultimately misdiagnosed the pathogen responsible for influenza, which he attributed to the opportunistic bacterium Haemophilus influenza (often referred to as “Pfeiffer’s bacillus”) rather than the yet undiscovered influenza virus.

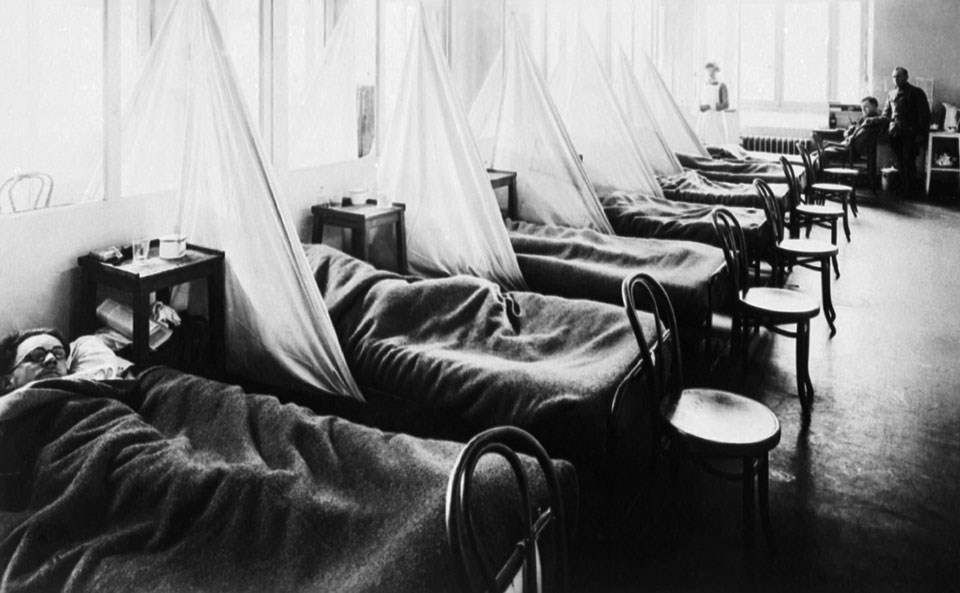

US Army Camp Hospital No. 45 Aix-Les-Bains, France, Influenza Ward No. 1. C. 1918.

This misdiagnosis had serious consequences during the next, and greatest, influenza pandemic in human history when doctors sought to find a therapeutic or vaccine for Pfeiffer’s bacillus to slow the spread of the flu pandemic in 1918.

The 1918 flu pandemic, the first and by far the most severe of five major flu pandemics in recent history (1918, 1957, 1968, 1976, 2009), afflicted 500 million patients and killed approximately 50 million people around the world between spring 1918 and its final recession in 1920. Like the pandemics in the ancient world, the 1918 influenza pandemic followed the movement of soldiers around the world in the final months of World War I.

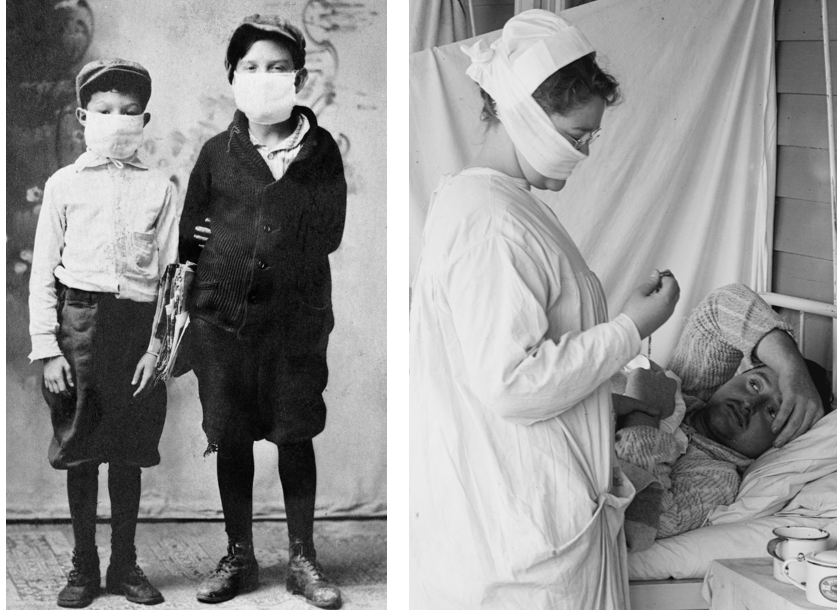

Amid the COVID-19 crisis, there are important lessons learned from 1918, such as the utility of wearing a mask and the importance of social distancing. People who neglected to do so or were slow in implementing quarantine measures suffered from far higher mortality rates.

Children ready for school during the 1918 flu pandemic (left). Nurse with mask and patient, 1918 in the Spanish Flu Ward of the Walter Reed Hospital (right).

At the same time, the wartime context greatly exacerbated the spread and severity of the pandemic because the mobilization of a war economy made real quarantine nearly impossible.

Furthermore, the misdiagnosis of the Pfeiffer’s bacillus as the cause of the pandemic led public health officials on a futile search for a flawed therapeutic to stem the tide of death. Only after three waves of influenza did the pandemic naturally run its course and the search for the virus and vaccine begin, a process that did not culminate until World War II made the need for an effective vaccine a medical imperative.

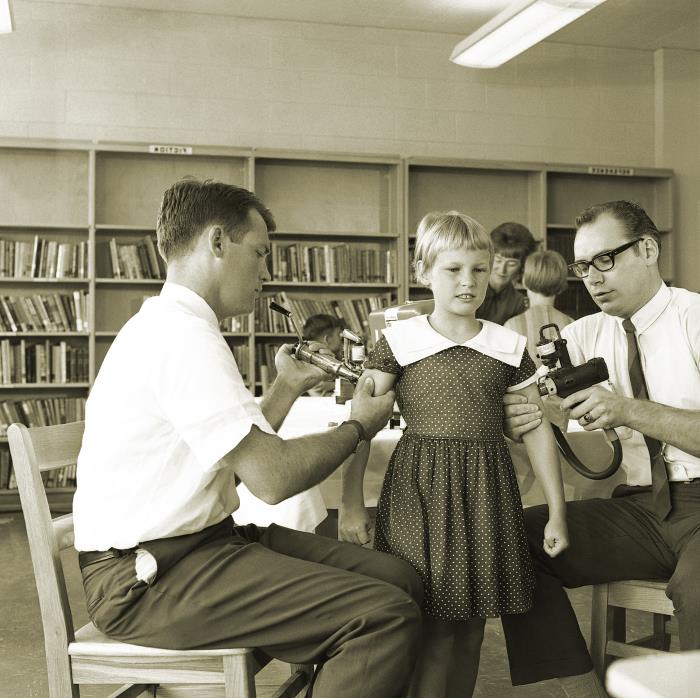

In the latter half of the 20th century, public health has made considerable advancements with the establishment of rapid vaccine deployment and global disease surveillance networks, such as the World Influenza Centre (chartered in September 1947), a subsidiary of the World Health Organization.

During the 1957-1958 “Asian flu” pandemic, for example, the swift spread of news of the pandemic through global surveillance systems allowed Maurice Hilleman at the Walter Reed Army Institute to begin rapid deployment of a vaccine that kept the death toll considerably lower (1 million worldwide) than most other pandemics in human history.

Yet other emerging pandemics in the past 50 years have continued to leave a deadly legacy.

Since the disease gained worldwide attention in the early 1980s, HIV has killed approximately 35 million people worldwide. At its outset, infection with HIV was nearly a death sentence for the patient. Since the 1990s, the development of anti-retroviral drug therapies has greatly increased the lifespan of HIV-positive patients.

Perhaps more significantly, the history of HIV reveals how pandemics can still carry a cruel stigma with them despite greater medical understanding.

Before scientists isolated the HIV virus in 1984, the pandemic was pejoratively termed “GRID” (Gay-related Immune Deficiency), because, in the United States, it disproportionately appeared among gay men and was found with greatest frequency in centers of gay culture. As an already marginalized group in the 1980s, gay HIV patients were accused of spreading a “gay cancer,” which led to their further social marginalization.

Pandemics in the 21st Century

Before COVID-19, we had been lucky in the 21st century. Indeed, we had not seen a pandemic cause such massive disruptions to global society since 1918.

In 2003, another coronavirus, SARS, reached pandemic levels because it followed our global travel networks, but cases only totaled 8,098. Tried and true public health strategies like quarantines and contact tracing swiftly contained it.

A SARS patient and their doctor in China during the 2003 outbreak.

Our most recent pandemic occurred in 2009. H1N1 was another influenza pandemic of the same strain that caused the 1918 flu.

In the United States alone it infected as many as 60.8 million residents and caused 12,469 deaths, according to the CDC. It disproportionately killed children and young adults, unlike a typical flu that tends to kill the elderly with greatest frequency. From this pandemic we learned that the H1N1 strain must annually be included in our flu vaccine.

We should pause and appreciate why we have largely forgotten these deadly companions. Medical knowledge in 2020 is vastly improved when considered across the fullness of recorded history.

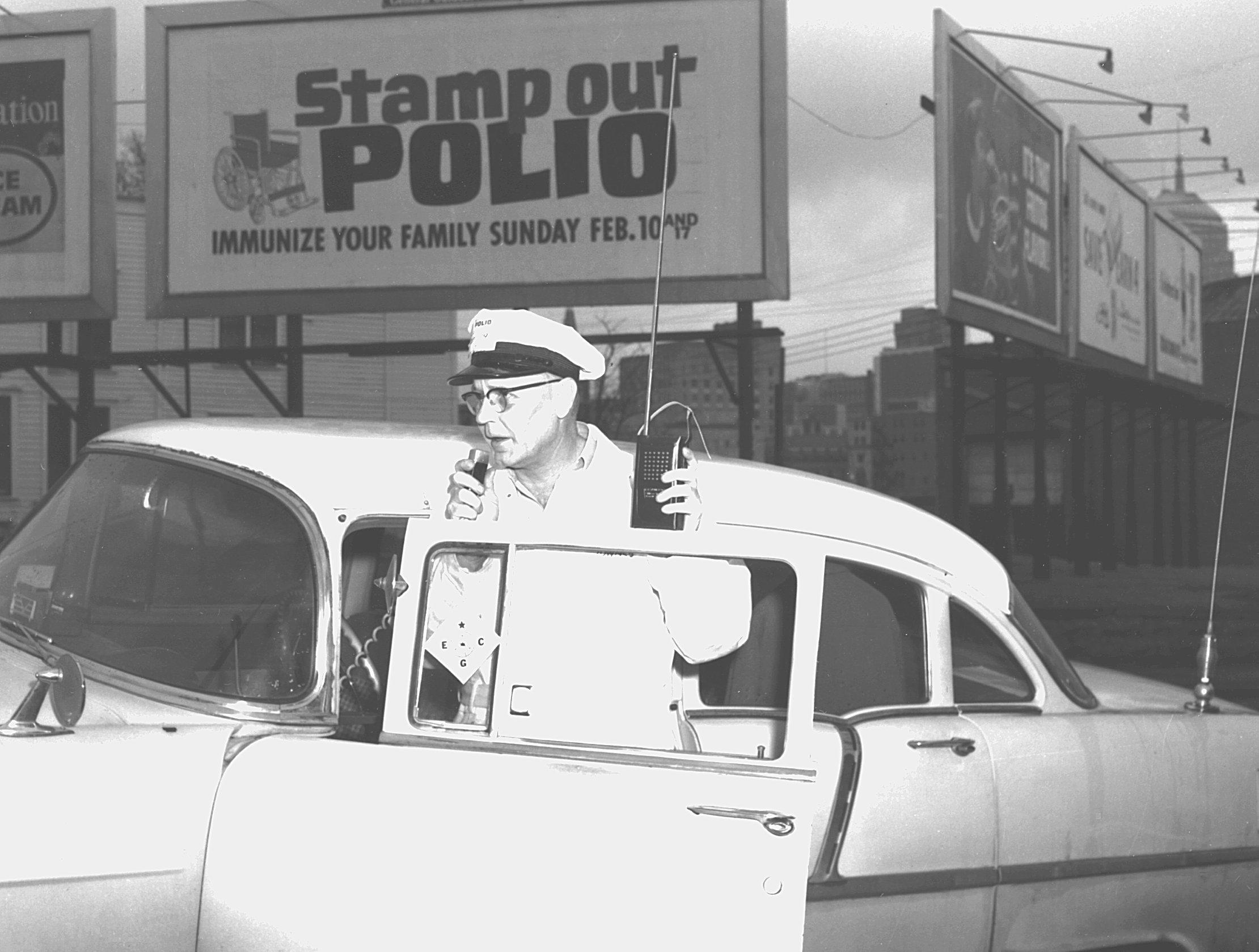

During the past hundred years we have made considerable advances, including the ability to identify viruses such as measles and polio, and in turn to develop crucial vaccines. In the case of SARS, and now COVID-19, we are able to isolate pathogens and gene sequence them in a matter of months.

But with our advanced-medical-science world of the 21st century, the general populace has become somewhat complacent, uninformed about the many past pandemics. Forgetting our history has made the death toll from COVID-19 feel all the more shocking.

Yet scientists are optimistic about the current pandemic. Projections foresee a vaccine for COVID-19—vaccines are the “holy grail” of pandemic mitigation—potentially being developed in a record 12 to 18 months.

A drive through COVID-19 testing site in Louisiana, 2020.

To date the fastest vaccine developed has been the original (and now discontinued) inactivated mumps vaccine, which took three years (1945-1948) to produce. If a COVID-19 vaccine is developed on this remarkable timeline, it will show just how far we have come in responding to pandemics from past to present.

Let us hope we do not see pandemic preparedness and community awareness falter along the way.

Read, Listen to, and Watch more from Origins on Pandemics and Coronavirus.

Dorothy H. Crawford, Deadly Companions: How Microbes Shaped Our History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

John P. Davis, Russia in the Time of Cholera: Disease under Romanovs and Soviets. London: I.B. Tauris, 2018.

George Dehner, Influenza: A Century of Science and Public Health Response. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2012.

J.N. Hays, The Burdens of Disease: Epidemics and Human Response in Western History, Revised Edition. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2009.

Lee Mordechai et al., “The Justinianic Plague: An Inconsequential Pandemic?” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116 (December 2019): 25546-25554.

William McNeill, Plagues and Peoples. New York: Anchor Books, 1976.