Comparing COVID-19 to HIV is, in many ways, like comparing apples to oranges: HIV is transmitted primarily through sexual contact or intravenous drug use, while COVID-19 appears to be airborne, transmissible through coughing and sneezing.

Yet, they both expose the underlying, often unspoken, issues afflicting the social worlds in which we live. For example, HIV and COVID-19 have both laid bare that stark racial disparities exist in population health and in access to quality medical care in the United States.

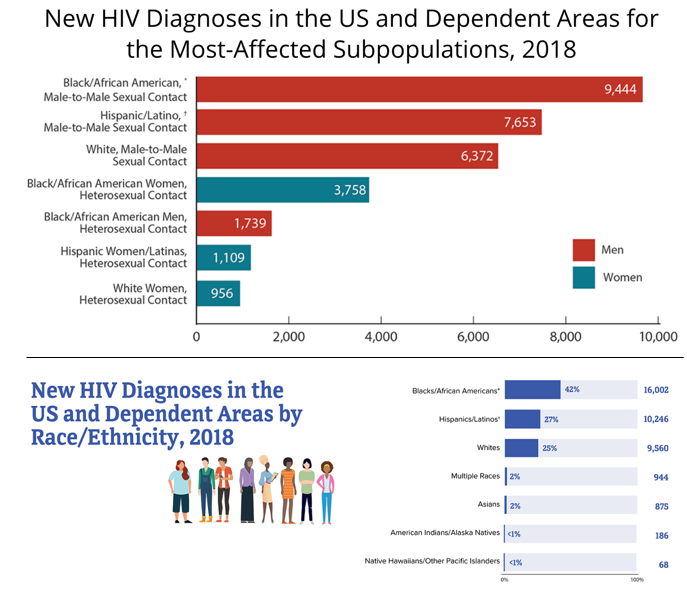

According to the CDC, Black men who have sex with men are the population most affected by HIV by race, gender, and sexuality (see Figure 1). In 2018, 42% of new HIV infections in the United States were among Black adults and adolescents (see Figure 2).

COVID-19 has revealed similar disparities: Black and Latinx residents of the United States have been three times as likely as white people to become infected. Nationwide, Black people are dying at a rate 2.5 times higher than white people. And in Ohio specifically, where only 13% of the population is Black, the Ohio Department of Health reports that 26% of COVID-19 cases, 32% of hospitalizations, and 19% of deaths are among Black residents.

These racial disparities point to the clear need for a social-justice based approach to public health that focuses on removing structural—namely, economic—barriers to accessing quality health care.

As we anxiously await the development of a vaccine for COVID-19, we have much to learn from the development of anti-retroviral therapy (ART), now used to prevent and treat HIV. Once a death sentence, HIV can now be managed as a chronic illness in most parts of the world. Yet it took decades of treatment activism in the United States and in Sub-Saharan Africa to make ART affordable, and it is still not widely available in many poorer countries.

A brief global history of HIV: 1981-2005

While HIV has a long and complicated history, experts consider the global HIV pandemic as having flared from roughly 1981-2005. HIV, or the Human Immunodeficiency Virus, was first detected in 1980 in California among a group of otherwise healthy young men who developed immune diseases like pneumonia.

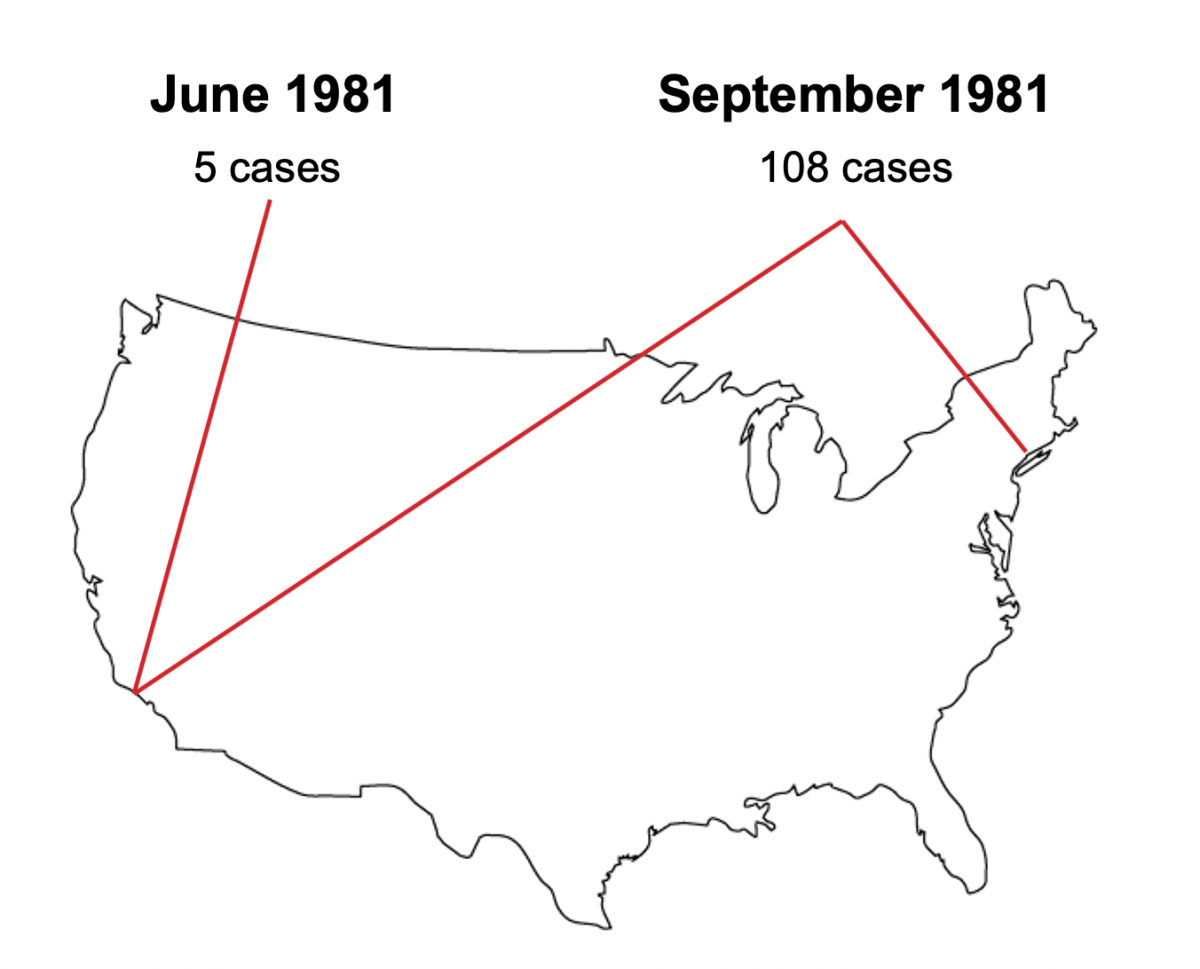

Figure 3: CDC reported cases of HIV over the summer of 1981. Image courtsey of the author.

In June of 1981, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control reported on the virus in five young men at three different Los Angeles hospitals. By the end of the summer, more than 108 cases had been reported, mostly from California and New York (see Figure 3). All but one of those cases were men, and over 90 percent of those infected stated that they were gay and sexually active.

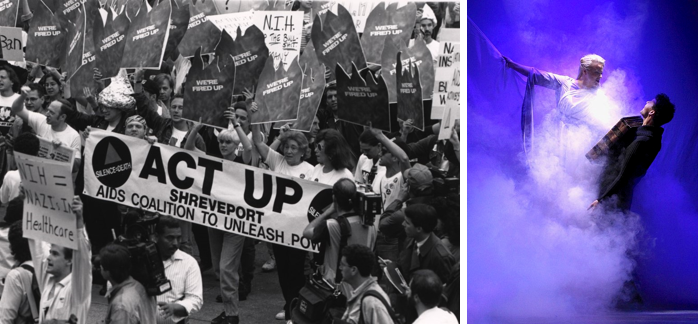

In the United States, HIV quickly became understood as a “lifestyle disease,” associated primarily with men who have sex with men. The association was drawn by national public health data, by activists from the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, or ACT-UP, an LGBTQ organization that advocates for the rights of those with HIV (see Figure 4), and by cultural productions, such as Tony Kushner’s Angels in America, which won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama (see Figure 5).

Figure 4: The AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power (ACT UP) (left). Figure 5: A scene from Tony Kushner's Angels in America (right).

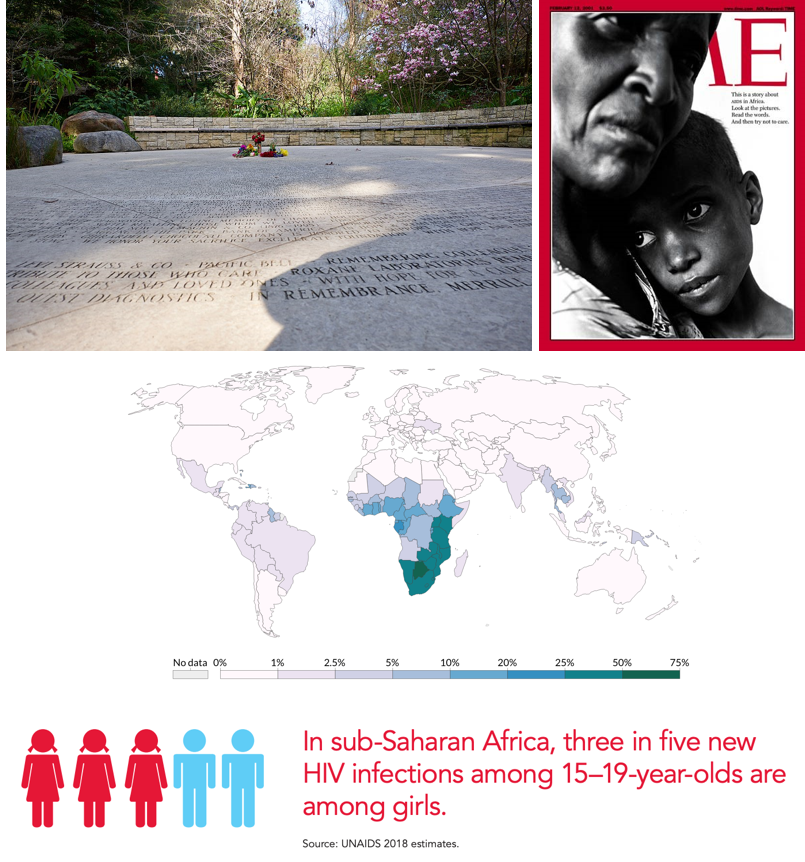

By 1992, HIV/AIDS was the leading cause of death for men in the United States. Since the beginning of the pandemic, more than 700,000 Americans have died (see Figure 6).

HIV/AIDS has also had devastating, and longer-reaching, impacts in Sub-Saharan Africa, so much so that AIDS has become almost indelibly associated with the African continent in the western public imagination (see Figure 7).

Africa’s first case of HIV was documented in southwestern Uganda in 1982, where it was known locally as “slim disease” because it causes extreme weight loss. Uganda, a landlocked country in East Africa the size of Oregon, had one the world’s worst outbreaks: by the early-1990s, HIV was killing one adult per every three households in its hardest-hit regions.

Figure 6: Names of victims inscribed in the National AIDS Memorial Grove in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park (top left). Figure 7: Cover of Time Magazine, February 12, 2001 (top right). Figure 8: HIV/AIDS deaths around the world in 2005, UNAIDS (middle). Figure 9: Estimates from UNAIDS 2018 data (bottom).

A decade later, most people living with HIV and more than 75% of deaths from AIDS around the world were in Sub-Saharan Africa (see Figure 8). The vast majorityof those infections were among young women, and they remain so today: in Sub-Saharan Africa, three in five new infections among young people ages 15-19 are in girls (see Figure 9).

Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) and Treatment Activism

Despite its devastating impacts, the HIV pandemic has receded: according to the World Health Organization, fewer than half as many die from HIV now than fifteen years ago. The availability of ART has led to a steep decline in the number of adults and children dying from the virus, yet access to ART was and remains unequally distributed both within the United States and globally.

In the US, researchers had developed effective ART by the late 1980s. However, the high cost of the medication, originally as much fifteen thousand dollars a year, prevented many who needed it from accessing it.

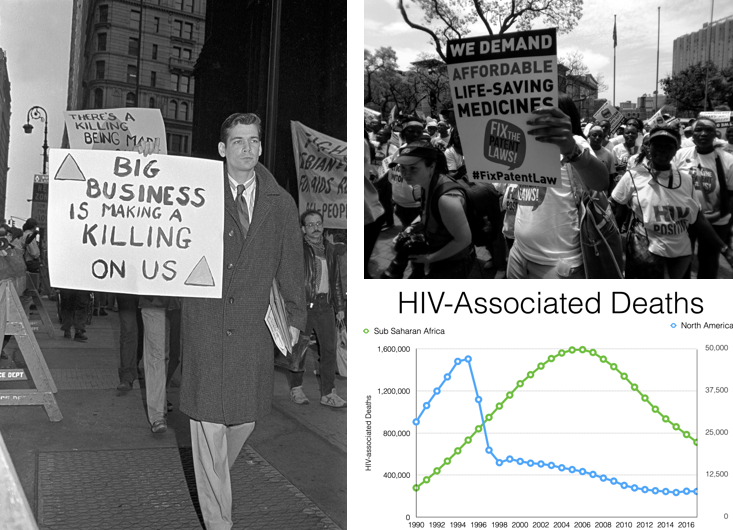

To demand affordable ART, ACT UP organizers targeted Wall Street and the government, which eventually established a federal funding mechanism called the AIDS Drug Assistance Program that made ART affordable and widely available (see Figure 10).

Figure 10: ACT UP organizers targeted Wall Street (left). Figure 11: Treatment Action Campaign activists, South Africa (top right). Figure 12: Global disparities in HIV-associated deaths. Graph by Jesse Kwiek, Department of Microbiology, The Ohio State University (bottom right).

By 1996, the death rate from HIV/AIDS in the U.S. began to decline. Researchers have estimated that ART saved over 3 million years of human life in the U.S. between 1989 and 2003.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, however, the high costs of ART prevented access to treatment for more than a decade. ART only became widely available on the continent in 2005, and only after activists from South Africa’s Treatment Action Campaign pressured the South African government and the World Trade Organization to block pharmaceutical companies’ patents on the life-saving medications (see Figure 11).

In other words, Africans had access to life-saving HIV treatment only ten years after Americans did (see Figure 12). Moreover, while more and more people in the United States and globally are managing HIV with treatment, UNAIDS estimates that only 62% of all people who need treatment can access it.

Lessons for COVID-19

Taking a global view of HIV/AIDS shows us that the populations most affected by the virus varied by geography and that nationality, gender, race, and socioeconomic status have shaped HIV vulnerability and access to treatment.

The lessons we have learned from HIV treatment activists also show us the need to regulate the global pharmaceutical industry so that profit-seeking cannot inhibit life-saving medications from reaching those who need them.

As “vaccine nationalism” for COVID-19 vaccines has already generated significant global concerns—and a record 5.4 million Americans have lost health insurance coverage amid the pandemic—the need for affordable, quality health care has never been more urgent.

Comparing COVID-19 and HIV must attune us to the importance of demanding that both the U.S. government and world health agencies ensure equitable access to life-saving testing, treatment, and vaccines.

Want to learn more about HIV/AIDS?

Fiction, Memoir, and Film:

The Great Believers, a novel by Rebecca Makkai (2018).

How to Survive a Plague, an Oscar-nominated documentary by David France (2012).

Pose, a television series produced by Ryan Murphy (2018-present).

Sizwe’s Test: A Young Man’s Journey Through Africa’s AIDS Epidemic, a journalistic biography by Jonny Steinberg (2008).

History and Anthropology of Medicine:

Scrambling for Africa: AIDS, Expertise, and the Rise of American Global Health Science, Joanna Crane (2013).

Impure Science: AIDS, Activism, and the Politics of Knowledge, Steven Epstein (1996).

AIDS and Accusation: Haiti and the Geography of Blame, Paul Farmer (1992).

“What is an Epidemic? AIDS in Historical Perspective,” Charles E. Rosenberg (1989).