The Russian invasion of Ukraine has created uncertainties in the world's grain markets and that, in turn, has focused attention on places which might experience hunger as a consequence. In fact, parts of sub-Saharan Africa have experienced food insecurity for decades and this month historian Andy Carlson looks at the long history of that problem and the efforts to alleviate it.

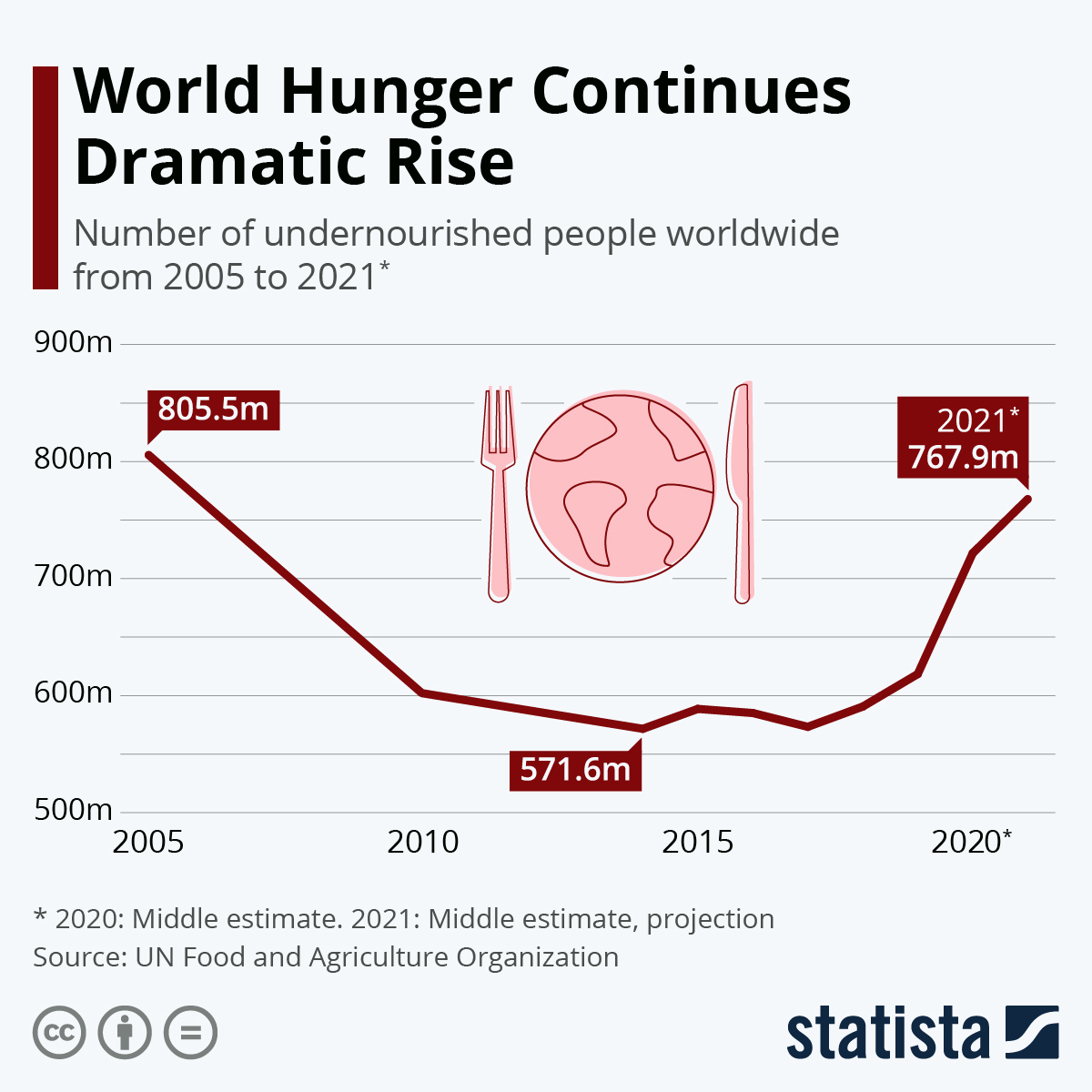

Since the 1950s, there have been dramatic decreases in the percentage of malnourished people in the world, from some 65 percent in 1950 to 25 percent in 1970 to 15 percent in 2000 and 9 percent in 2020. Remarkably, during this same 70 years, global population has risen from 2.5 billion people to 8 billion.

Yet in November 2022, when the human population reached 8 billion, the United Nations announced “the worst food crisis in modern history.” The phrase “global polycrisis” captures the complexity of events driving up world hunger over the past two or three years: the rise of authoritarian regimes, multiple intra-state conflicts, the COVID pandemic, the war in Ukraine, supply chain disruptions, inflation, and extreme weather.

A 2022 United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) report, The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World (2022), begins with the statement that “the challenges to ending hunger, food insecurity, and all forms of malnutrition keep growing.” Nowhere are those challenges more pressing than in large parts of the African continent.

Food, Population, Politics

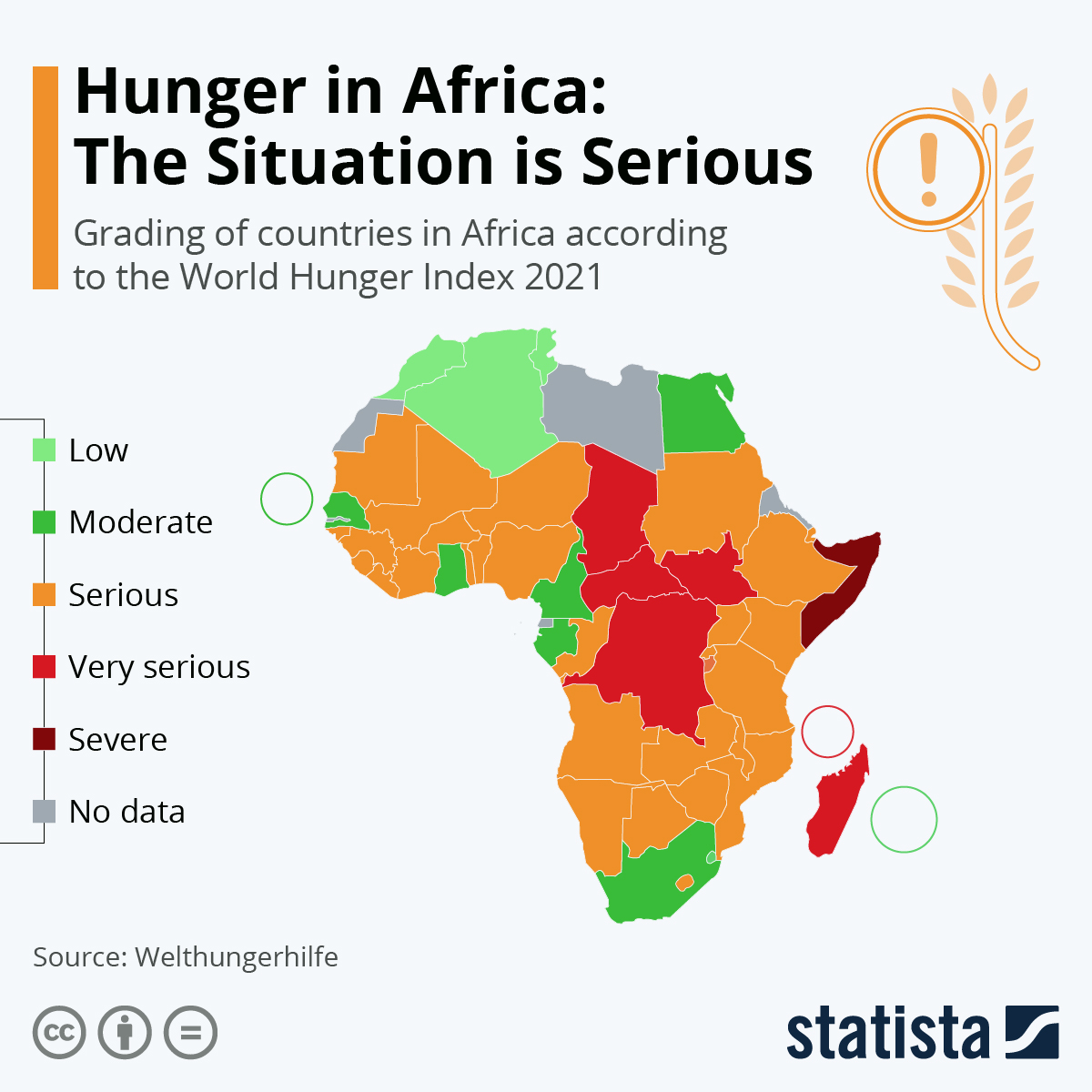

The connection between the current hunger crisis and population growth is indirect and complicated, but the situation in Africa looks more direct. For while population growth is slowing over much of the developing world, it is not slowing in certain regions of Africa, particularly in central and eastern Africa, where the hunger crisis is most severe.

Some of these states—notably Burkina Faso, Niger, the Central African Republic, Somalia, Ethiopia, and South Sudan—have entered a polycrisis that will be difficult to exit. It is hard to imagine that continued population growth in Africa—perhaps doubling from the current 1.4 billion to 2.8 billion by 2050—will make peace and stability easier or alleviate the hunger.

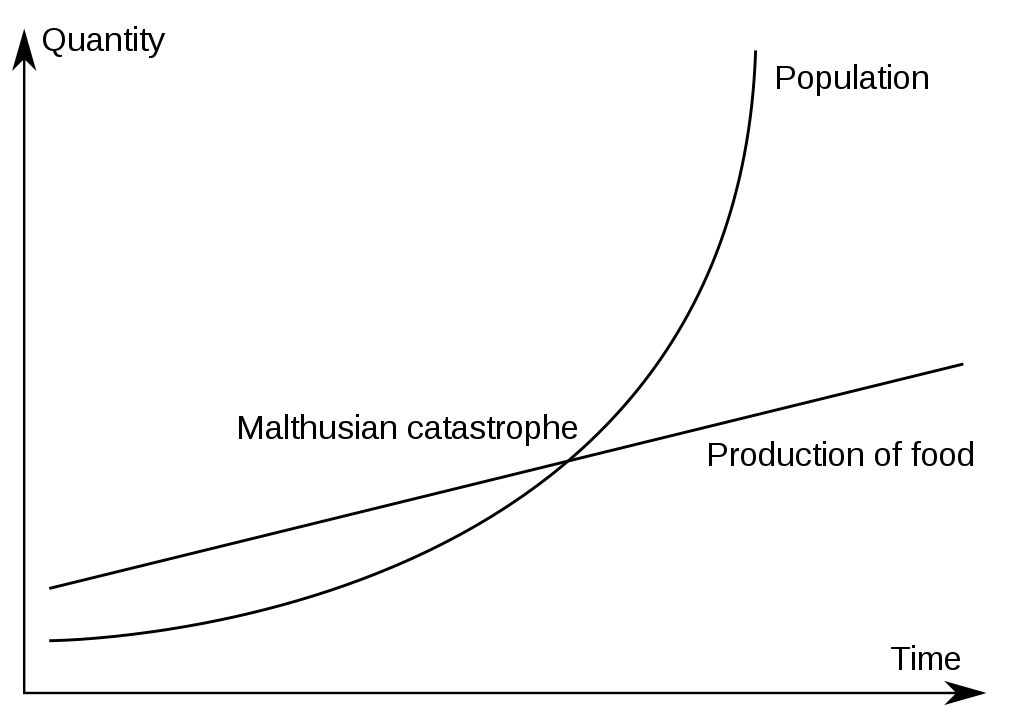

The idea of carrying capacity—that particular societies or city states must balance environmental resources and population—goes back at least to Plato’s Republic, written in the fourth century BCE. Since 1798, when Thomas Malthus published his maxim that population grows geometrically while food supplies increase arithmetically, scholars and policy makers have tried to understand that balance in the context of a rapidly growing global population.

So-called population optimists (or cornucopians) such as Julian Simon have argued that human ingenuity can solve all problems. Indeed, Green Revolution agronomist Norman Borlaug demonstrated that a new scientific agriculture based on the use of genetically modified seeds and fertilizers would be able to feed growing populations in Mexico and India. Perhaps a Green Revolution is possible in Africa, but so far efforts have not been successful.

Population pessimists (or catastrophists) such as biologist Paul Ehrlich, notably in his book The Population Bomb (1968), have argued that the limit of the earth’s carrying capacity is between 2 and 3 billion people. But while breathing some life into Malthusian economics, his prediction has clearly been proven wrong, at least to this point.

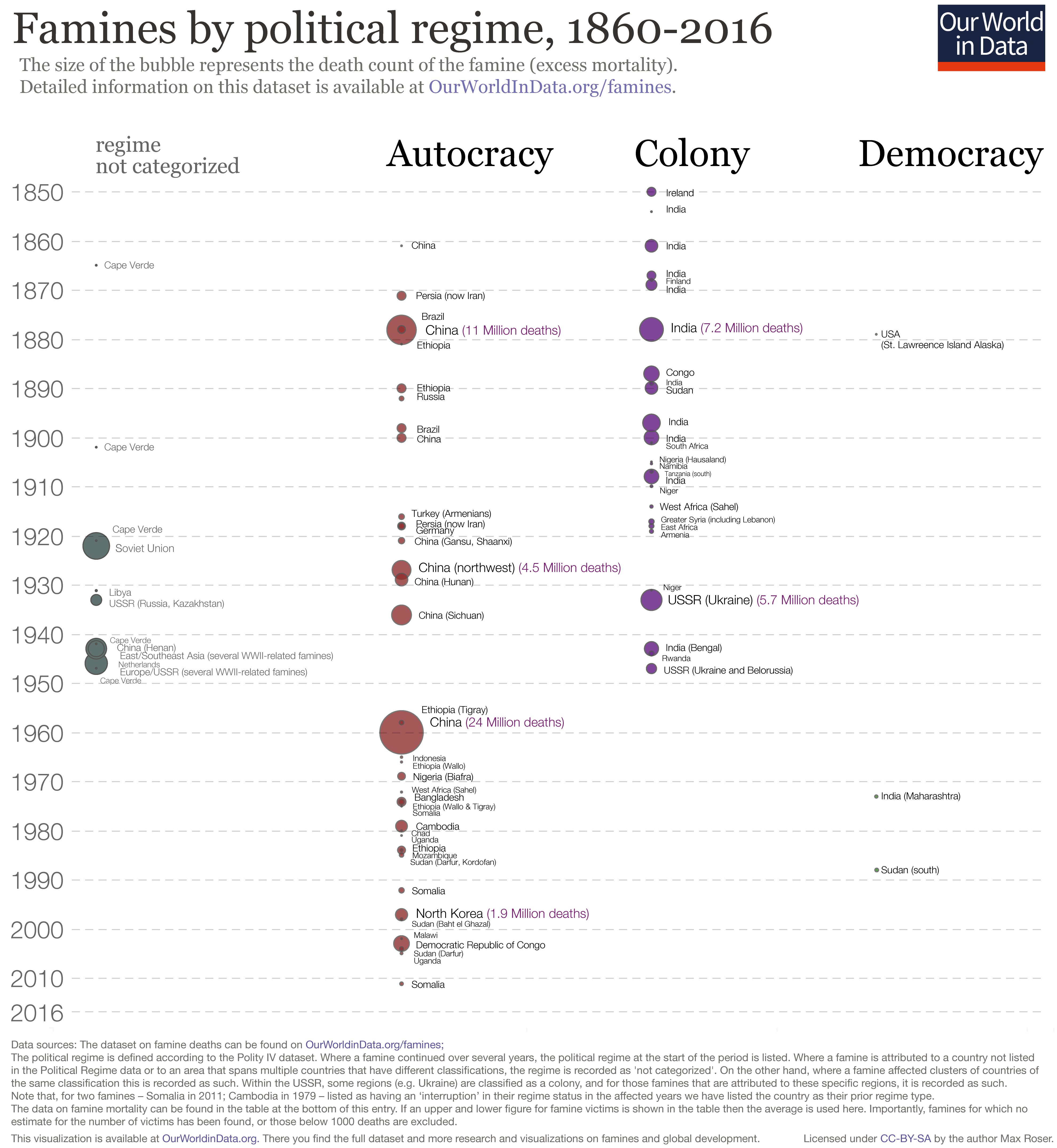

Scholars such as Nobel prize winning economist Amartya Sen emphasize the capacity of states to prevent famine. Over the past 40 years, that argument has guided multiple policy initiatives, including the UN’s state-centered approach to feeding the world.

And it has been mostly successful. In his 2018 book, Mass Starvation: The History and Future of Famine, Alex de Waal notes “a spectacular decline in famines and famine mortality” since the 1980s.

Yet over the past year many people, including techno-optimist Bill Gates, have noted that the world is not going in the right direction. Since the formation of the FAO in 1945, leaders have called for “the eradication of hunger.”

In 1974, Henry Kissinger called for a 10-year timetable. In 1996, at the first World Food Congress, the goal line was set at 2010. The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), approved by 145 member states in 2000, set the deadline at 2025. And Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) approved by 181 states in 2015, set a goal of 2030, although current predictions are that 600 million people will remain undernourished even then.

In the abstract, there are sufficient supplies of major food commodities to feed more than 8 billion humans. Yet in 2022 more than 3 billion people—40 percent of the total world population—did not have access to adequate supplies of food, according to the FAO.

More than 400 million of these severely undernourished people live in South Asia, and 250 million live in Africa—meaning that more than 20 percent of Africans are experiencing severe food insecurity. The hunger situation in Eastern and Central African states is particularly dire.

Hunger has not been eradicated because of the fragility of the states charged with guaranteeing the food security of their own peoples in a world reliant on a global food system. When these states cannot meet their people’s expectations, including a sufficient supply of affordable food, crises ensue. If there is a global polycrisis, people in these states suffer and some even die as a result of starvation.

The Long History of Food Insecurity in Africa

Food insecurity in Africa has a deep history. Archeological mapping of the Sahara suggests ancient migration from urban centers in the Sahara towards riverine areas along the Nile and Niger starting 7500 years ago.

Satellite images of Lake Chad show water levels declining rapidly since the 1950s. The African Sahel countries face one of the most hostile climate situations in the world, one of the highest population growth rates in the world, and serious conflict between farming and pastoral communities.

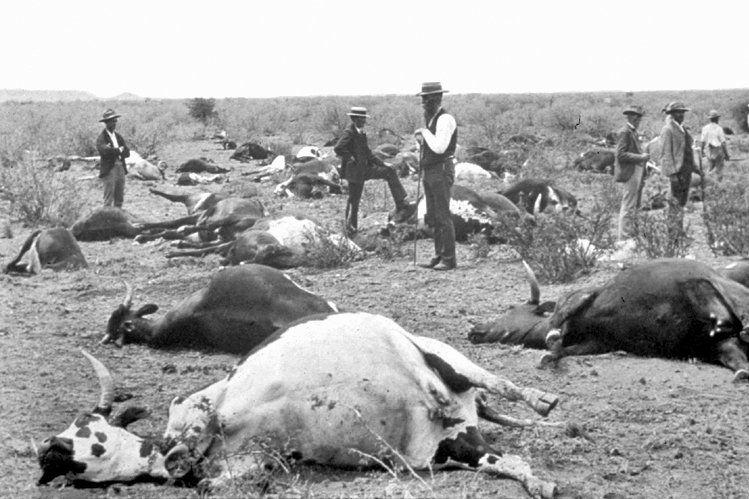

The Horn of Africa has experienced episodic drought and famine for millennia because of shifts in rainy seasons due to vicissitudes in the Indian Ocean monsoons. In the 1890s a rinderpest epidemic devastated livestock populations and the people who depended on them. In Ethiopia, approximately 10% of a population of perhaps 10 million people died. In Sudan 2 million people died from starvation and war.

In 1972-73 an estimated 200,000 Ethiopians experienced death from starvation in the northeast region of the country. The famine was one of the factors leading to the overthrow of Emperor Haile Selassie in 1974. Another famine hit northeastern Ethiopia in 1984-85, when some 600,000 died. This was one of a longer chain of events leading to the overthrow of Mengistu Haile Mariam’s dictatorship in 1991.

In most of these cases there is a strong connection among famine, conflict, and political instability.

Creating the Idea of Global Food Security

In 1942, as President Franklin Roosevelt was planning to restart the League of Nations as the United Nations, hunger was the major concern. Australian economist Frank McDougall argued at the White House that food should be the first of the global issues taken on by the United Nations.

A year later at a conference in Hot Springs, Virginia, 44 governments agreed to start a permanent organization to address food and agriculture as a global problem. In 1945, 34 governments signed the constitution of the new FAO eight days before the formation of the UN.

The UN and the FAO continue to envision a world without hunger. Many member states and global institutions concur.

Yet in 1945, the scope of nutrition and malnutrition problems was unclear. There were no reliable historical records on malnutrition—certainly not on a global scale. So as it dealt with postwar food crises, particularly in Europe, the FAO launched a series of food, agriculture, nutrition, and soil studies which would provide new metrics for understanding hunger.

In 1950 the FAO coordinated a baseline World Census of Agriculture, which surveyed 81 countries.

When the UN Economic and Social Council asked the FAO to monitor food supplies and impending famines around the world, another series of studies was launched on problems that resulted in food crisis—desert locusts, supply chains, seeds, international food standards, and so on—as part of a campaign to “eradicate hunger in the world once and for all.”

A high point in the history of the FAO came at the 1996 World Food Summit when 10,000 world leaders and 186 states met to discuss the new concept of “food security.” Two results were the Rome Declaration on World Food Security, which affirmed every person’s right to safe and nutritious food, and the World Food Summit Plan of Action, which renewed the global commitment to eliminate hunger and malnutrition.

A World Food Summit in 2002 reaffirmed the commitment to halve global hunger. This commitment was reinforced by the Millennium Development Goals and the Sustainable Development Goals approved by the UN in 2000 and 2015.

Confronting Hunger In Africa

Until the 1960s, most of the world’s recognized famine crises happened in Europe and Asia. The first major test of the world’s new commitment to solving famine in Africa of came in “the crisis in the Sahel.” Over a period of seven years, starting in 1968, the FAO supplied cereals, seeds, and insecticides to Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso.

In his keynote address at the 1974 World Food Conference, U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger committed the United States to a campaign to ensure “no child will go to bed hungry within ten years.”

The Fifth World Food Conference in 1984 reported that the number of undernourished people stood at 800 million. That year more than 30 African countries experienced famine and death by starvation.

Somalia, Eritrea, and Ethiopia had the highest rates of malnutrition in the world. In response, a global Feed the World campaign raised millions of dollars to deliver 7 million tons of cereals to 21 countries.

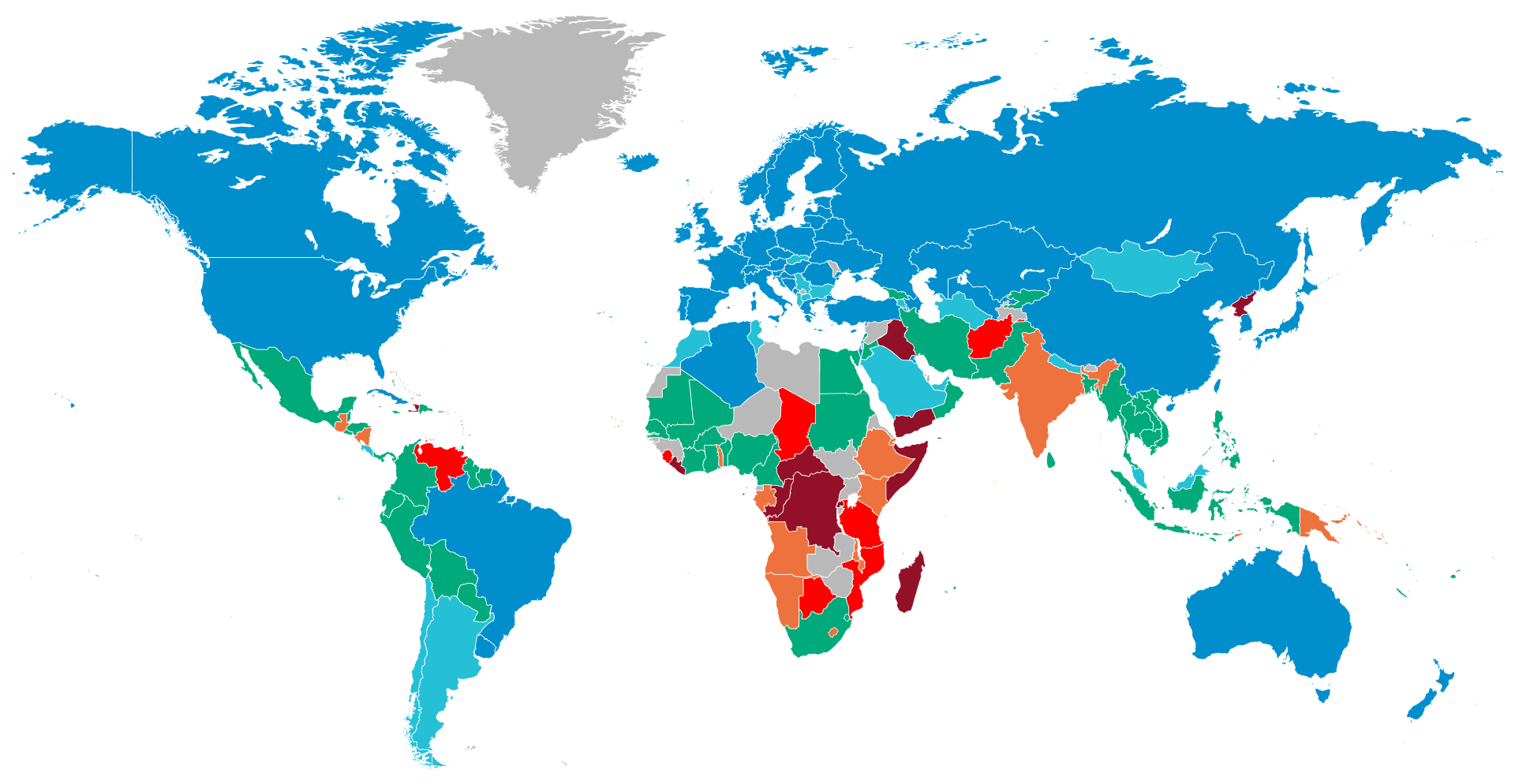

Yet despite the success of the MDGs globally, accomplishments in Africa were less impressive. In Asia the prevalence of undernourishment (PoU) fell from 13.9 percent in 2005 to 8.0 percent in 2015. In Latin America and the Caribbean, it declined from 9.3 percent to 5.8 percent. In Africa the PoU declined from 20.7 to 15.8 percent.

The most depressing feature of the measures of the prevalence of undernourishment, however, were the statistics from Eastern and Central Africa. While PoU was 5.2 percent in Northern Africa, 7.4 percent in Southern Africa, and 10.1 percent in Western Africa, in Eastern Africa it was 24.4 percent and in Middle Africa it was 26.3 percent. Progress had been made, but not as much as elsewhere.

Somalia and Ethiopia: Similar Challenges, Different Results

Since the 1990s, Ethiopia and Somalia have fared differently in the face of similar regional weather patterns.

Somalia’s worst famine in came in 1992, a year after the overthrow of authoritarian leader Mohammad Siad Barre. The UN and the United States briefly intervened in 1993. But Somalia was not able to re-establish a stable state that could govern its three major regions.

In the 2000s, Somalia was less successful than Ethiopia in feeding its people, despite similar weather patterns. In Ethiopia the short rainy season (belg) from February to May and heavy rainy season (keremt) from July to October have failed several times to provide enough water for crops, most notably in 2002, 2011, and 2015. In Somalia the heavier gu rains (May, June, July) and hayr rains (October to December) have followed a similar pattern.

Several scholars have noted that Ethiopia has been more successful at preventing famine than Somalia. The main reason, according to Joshua Busby, is the differences in “the intersection of state capacity, inclusion, and foreign assistance.”

As of 2022, a combination of continued civil war and drought has made 7.8 million people in Somalia food insecure, and “500,000 children [are] at risk of death by mid-2023,” according to UNICEF spokesman James Elder.

The federal government in Mogadishu is reluctant to ask for international aid because it does not want to discourage investment. Lack of food spurs radicalization which in turn discourages market solutions to food security. This is the long tail of a polycrisis.

Ethiopia is also experiencing drought, flooding, locust infestations, and civil war. As the population has passed 120 million, the economy has slowed and inflation has skyrocketed to more than 30%. One credible source estimates 600,000 deaths in northern Ethiopia since 2020, tens of thousands of these from starvation.

Hunger Is Not Eradicated

In 2000, the goal of eliminating hunger took on greater urgency as the UN committed to achieve eight global goals by 2015, primarily focused on conditions in the developing world. Goal one was to “eradicate extreme hunger and poverty.”

When the MDGs were replaced in 2015 by the SDGs, another nine goals were added. The first was “ending poverty in all its forms everywhere”; the second was to “end hunger” and “achieve food security.”

Over the past 30 years, the percentage of undernourished people in the developing world has declined from 23% in 1990-1992 to 12.9% in 2014-2016. In 2015 and 2016, the FAO gave 65 countries awards for halving the percentage of their people suffering from hunger.

Yet from conference to conference, decade to decade, eradicating hunger almost always seems out of reach.

One notable feature of the globalization of the world food system is that the day-to-day cost of a healthy diet is similar around the world, regardless of where you live. In 2022 the UN calculates this as between $3.64 and 4.88 U.S. dollars per day. What is not similar is ability to pay for food. In North America and Europe, 1.6% cannot afford a healthy diet. In East Africa, 85% of the population cannot afford a healthy diet.

Another global pattern for food insecurity is that individuals with more income are more food secure: women are less food secure than men, and children are less food secure than adults. In 2021, 22.2% of all children in the world (149 million individuals) were stunted as a result of severe food insecurity. Three quarters of these children live in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia.

As we enter 2023, the International Red Cross Red Crescent Movement (IRCRCM) warns that “crisis fatigue is not an option as the global hunger crisis deepens.” The problems are not just in Africa—they also stalk Yemen, Pakistan, Syria, and Afghanistan, places scarred by conflict.

According to the IRCRCM, “Sub-Sahara Africa is experiencing one of the most alarming food crises in decades—immense in both its severity and geographic scope.”

In such a real time emergency, the solution is donations from governments and people who have the resources. At this point, the Red Cross and the World Food Program have received less than a small fraction of what they project is needed to avoid massive death by starvation.

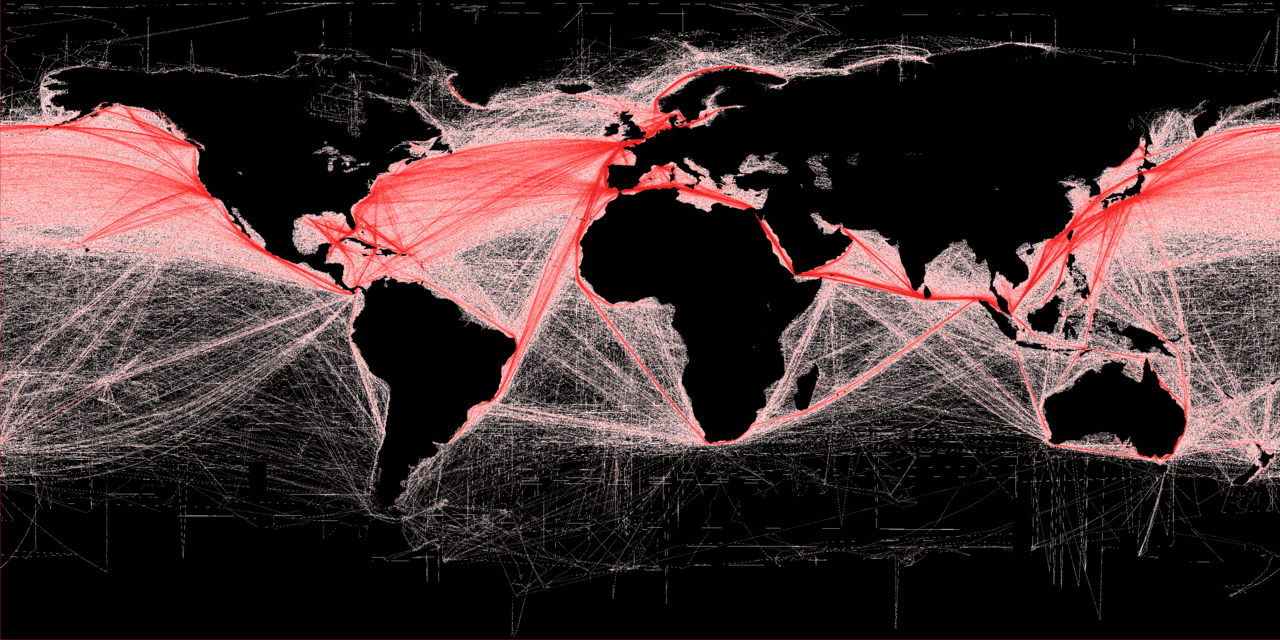

So why are there such severe food crises in the world, and particularly in Africa, when global food supplies are not the issue? The most general answer is that much of Africa remains in what anthropologist James Ferguson calls “the global shadows.”

Whether it is states on the Indian Ocean such as Somalia or Madagascar, or states in the interior such as the Central African Republic or Democratic Republic of Congo, the benefits of global trade are very far away. The obvious long-term solution is better transportation networks which can tie these places into the global food system.

In the medium term, the FAO’s advice to its member states to rebalance government allocations in favor of local and regional food systems makes sense. While there is the global capacity to feed 8 or 10 billion people, even when supply chains run perfectly, several hundred million people are left out because they live too far from food networks or they live in the midst of conflict or they are prevented from moving to places where food supplies and prices are not a problem.

In the short term, the only real solution right now is for the rest of the world to lend a helping hand in the form of emergency food assistance. Hunger is not eradicated.

Busby, Joshua W. States and Nature: The Effects of Climate Change on Security. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2022.

De Waal, Alex. Mass Starvation: The History and Future of Famine. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2018.

Ferguson, James. Global Shadows. Africa in the Neoliberal World Order. Durham: Duke University Press, 2006.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 70 Years of FAO, 1945-2015. 2015.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World. Repurposing Food and Agricultural Policies to Make Health Diets More Affordable. 2022.

Rieff, David. The Reproach of Hunger. Food, Justice and Money in the Twenty-First Century. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2015.

Smil, Vaclav. How the World Really Works: The Science Behind How We Got Here and Where We’re Going. London: Viking, 2022.