After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Western politicians and commentators trumpeted the triumph of liberal democracy. Around the world, it seemed, democracy was on the march—in the former communist regimes of Eastern Europe, in large parts of Africa, and elsewhere in the developing world. Now, even the most optimistic must concede that the democratic wave has stalled and, in many places, is retreating. Voters across the globe have embraced some version of “populism” as a backlash against liberal democracy. This month we’ve invited three scholars to examine the rise of nationalist populism in three countries: the United States, the Philippines, and Hungary.

The United States: Anger in the Room

by Marc Horger

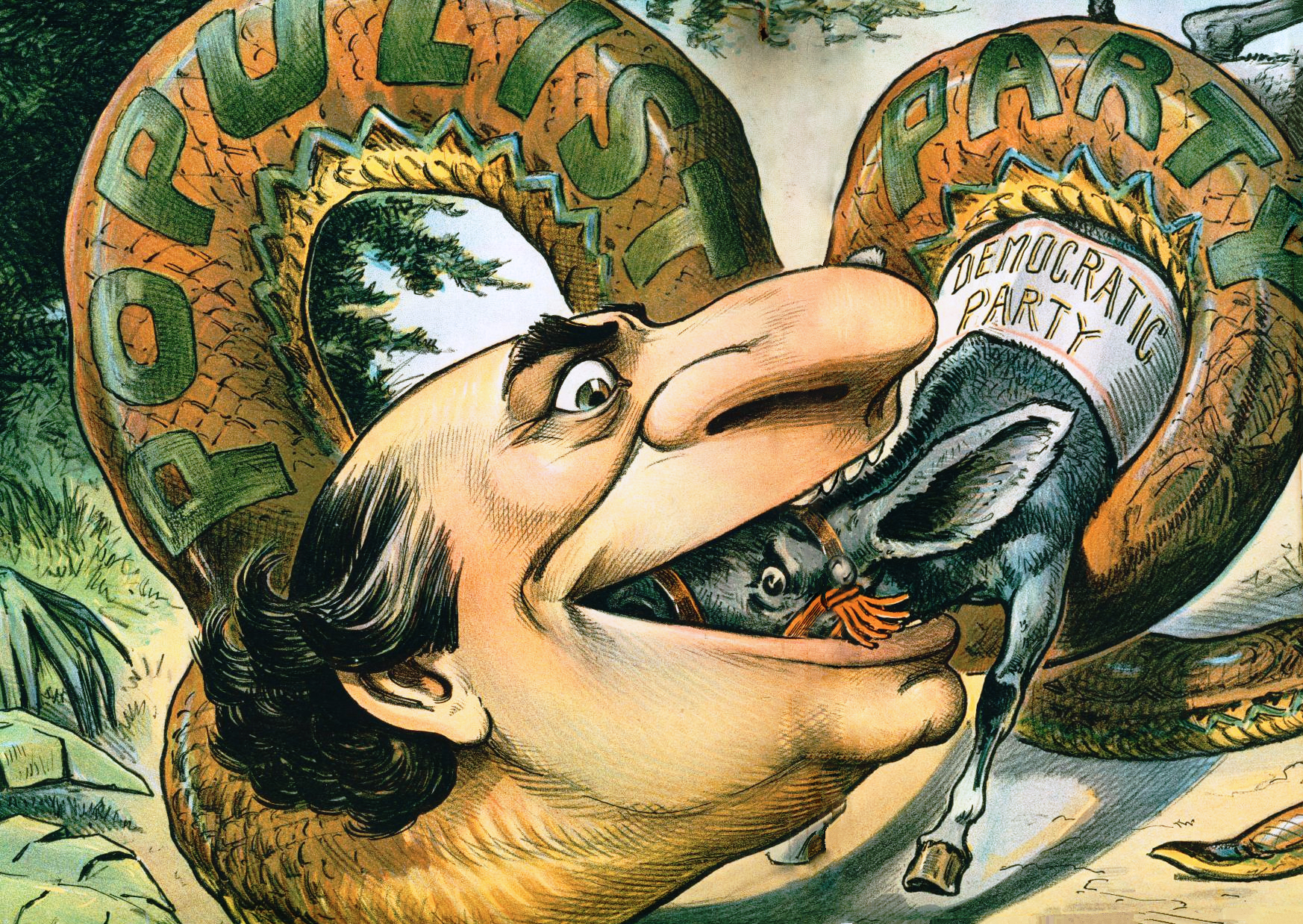

In 2011, I penned an article for this publication on the subject of populism in American politics. At the time, I expressed skepticism that the term “populist” represented an effective analytic category, at least on the basis of policy. “From its first appearance in the political vernacular, ‘populist’ has been an adjective expressing an attitude—a popular anger against elites perceived as distant from and antagonistic to the struggles of ordinary Americans—more than delineating a coherent set of political beliefs,” I wrote.

Given the wide variety of political figures and movements labeled “populist” at one time or another in American history, the term functions more as a diagnosis than as a description. “First and foremost,” I noted, “contemporary use of the term assumes there is anger somewhere in the room. This anger may be justified or irrational; organic or ginned-up; economic, racial, cultural, or regional; but without palpable anger and resentment, most observers would probably choose different terminology.”

The piece ran in April 2011. That same month, Barack Obama experienced what was once regarded as the best weekend of any politician in living memory.

President Barack Obama at the White House Correspondents’ Association Dinner in 2012 (left). Obama, Vice President Joe Biden, and members of the national security team in the White House Situation Room receiving updates on Operation Neptune’s Spear, the mission against Osama bin Laden, in May 2011 (right).

On the morning of Friday, April 29, he gave the go code on Operation Neptune Spear, the Navy Seal operation that captured and killed Osama Bin Laden. Saturday the 30th, with the raid on temporary hold due to inclement weather, Obama destroyed at the White House Correspondents’ Dinner, delivering sharp comic material about his recently released long-form birth certificate and roasting, to his face, one of the nation’s leading “birther” conspiracy theorists, reality-TV star and possible billionaire Donald Trump. By 11 p.m. Sunday, Osama Bin Laden was dead, and so, it seemed, was birtherism.

The events of this weekend have since been reevaluated.

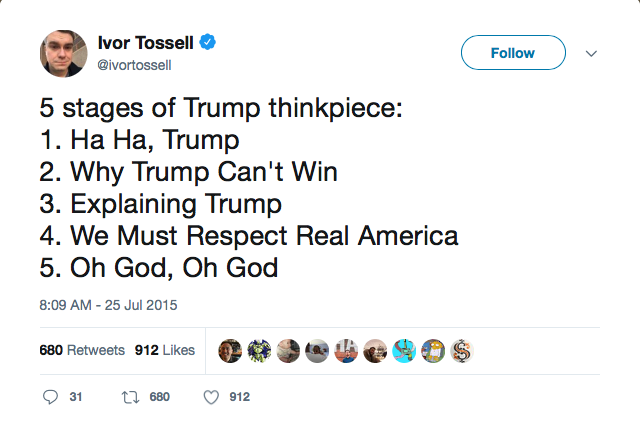

A July 2015 Tweet from Ivor Tossell, a BuzzFeed columnist.

Now that we are here at Stage Five of Ivor Tossel’s “5 stages of Trump,” perhaps it is time to think again about populism as a force in American and global politics.

The first and most humbling point is that a large percentage of the people qualified to pontificate about the role of this or that movement in the history of American politics spent the 2016 cycle reassuring people that “President Trump” was an obvious impossibility. This fact alone suggests that key elements of American politics may well be fundamentally different moving forward, and in ways that will be difficult to predict.

Candidate Donald Trump at a 2016 campaign rally in Arizona.

One longstanding element of the populist style in American politics to which the Trump phenomenon seems to conform is the adoption of an “outsider” stance on the stump as a means of establishing a visceral connection with “ordinary Americans.” Yet most of these “outsiders” were in fact conventionally credentialed public figures executing a premeditated political strategy.

George Wallace, for example, either held or sought public office nearly every day of his adult life; Sarah Palin, for another, was actually governor of Alaska for a while. The list of politicians for whom a flagrant lack of qualification for any kind of public trust is precisely the explanation for their success is actually quite short.

Governor George Wallace facing off against Deputy U.S. Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach to prevent the University of Alabama from being desegregated in 1963 (left). A novelty clock made for Lester Maddox’s 1983 congressional campaign (right). Governor Sarah Palin in her office in 2008 (bottom).

Of those who actually reached high office, the closest analogue is probably Lester Maddox, the axe-handle-toting white supremacist who wound up governor of Georgia in the late 1960s because of his notoriety as a bigot; but even he had previously sought public office. The fact of President Trump may well open electoral politics to entirely new categories of potential public figure, independent of underlying changes in political coalitions or policy choices.

A second potentially disturbing development in the populist style is the re-emergence of an openly, ostentatiously white-nationalist conservatism.

Protesters outside the Supreme Court during oral arguments on Trump’s travel ban in April 2018.

Since the days of Wallace and Maddox, appeals to racial resentment remained a component of conservative politics, but they grew increasingly coded rather than overt. Trump’s appeals are less coded. This has manifested itself not just on the stump, but also in policy. Before the Supreme Court ruled in his favor, Trump’s travel ban for example, kept failing in court because Trump is unable to talk about it in code.

Day-to-day enforcement of migration and immigration policies has been affected as well. During the successes of the Obama years, Democrats predicted that political demography was on their side in both the short and long term, and that a younger, better educated, and more diverse electorate would trend strongly in their favor.

Many Republicans more or less agreed; after Romney’s loss in 2012, the party prepared a post-mortem arguing that the Republican message needed to be more welcoming to younger, non-white audiences, particularly on issues of immigration and social policy, or the party would atrophy. Trump became the Republican nominee not just by running against the Age of Obama, but by running against the 2012 GOP post-mortem.

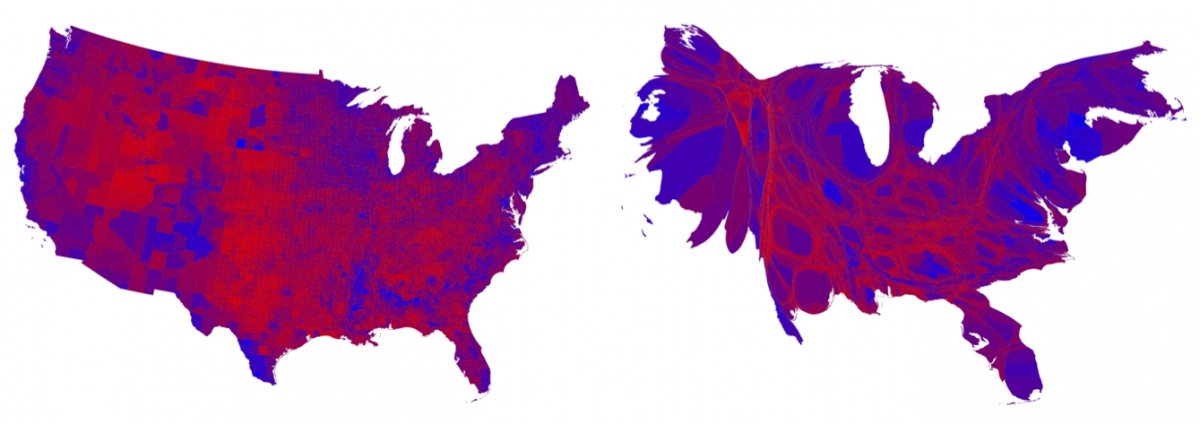

A map of the U.S. with the popular vote from the 2012 election shaded to depict the way each county voted (left) and that same map with each county rescaled in proportion to its population (right).

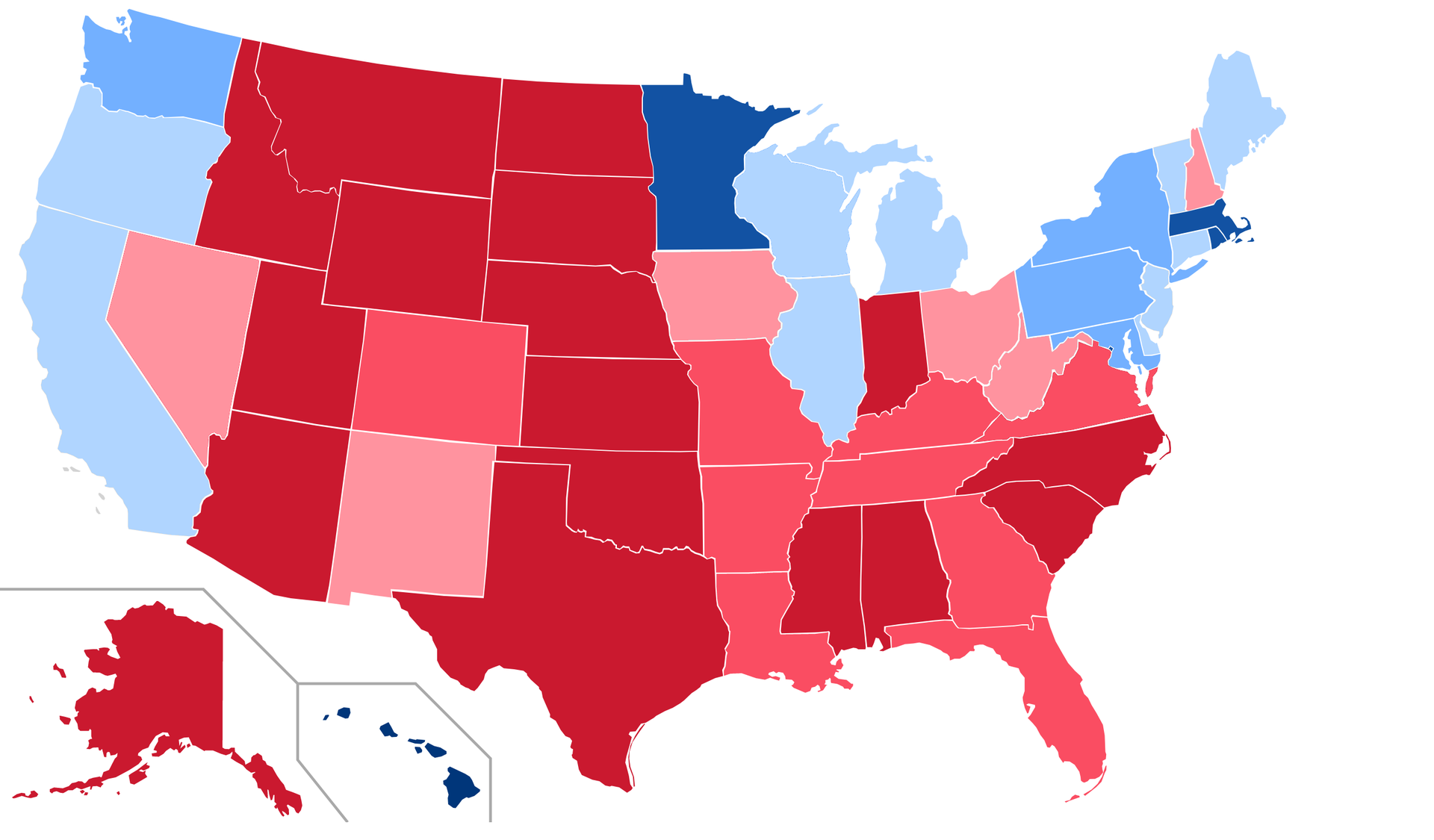

The trend in Republican messaging has been away from an inclusive “big tent” and toward a politics of immigration restriction, anti-internationalism, and cultural resentment. This is on trend, unfortunately, with nationalist conservatism elsewhere in the western world.

It remains to be seen how effective these messages will be at the national level moving forward. They seem likely to dominate one of the major party coalitions for the foreseeable future, however. Identity politics may well be less coded and more forthright in the near term, in ways likely to have real policy impact on real people. Of course, identity of one type or another has always been central to American political party alignment, and not just on the right.

A third possible development to monitor is whether we may have reached an inflection point of party coalition realignment. The so-called Sixth Party System alignment has been with us for a while now, and the 2016 electoral map was surprising not just in terms of outcome, but also in terms of regional shifts. In particular, northern rural and small-town areas voted more like the white south, and major southern metros like Atlanta and Houston shifted blue.

The result was a map on which the rural-urban divide became more salient nationwide and cut sharply across other geographic factors. This is a recipe for increased focus within both party coalitions on the tension between cosmopolitanism and homogeneity.

This tension is a central concern throughout western political society at the moment. Furthermore, just as the current political equilibrium in the United States is a bit long in the tooth when judged historically, so is the international equilibrium shaped by American engagement with the 20th century.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill in 1941 after they agreed on the Atlantic Charter, a policy statement defining the Allied goals for the postwar world, which inspired many international agreements (left). President Obama speaking to the people of Berlin in front of the Brandenburg Gate in 2013 (right).

The Atlantic Charter is 76 years old; the NATO alliance is 69; the map of the world over which they preside still looks a lot like the one drawn at Versailles in 1919. One author of the Atlantic Charter is now trying to leave the European Union; the other just spent the last 18 months bullying its closest allies and questioning the basic premise of NATO.

This returns us to “the anger in the room.” Trump is currently president at least in part due to his ability to convert his literal anger in a literal roominto successful political messaging at the national level. This is currently the functional definition of “populism” in American politics.

The Philippines: Rodrigo Duterte, Populism and Revolution

In February 1986, public outrage finally erupted at Philippine president Ferdinand Marcos after 13 years of martial law. Marcos’s strongest political rival, Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino, Jr., had been assassinated three years earlier, possibly on Marcos’s orders, and there was evidence of tampering with the February 7 presidential election.

Over a million protesters gathered on Epifanio de los Santos Avenue (EDSA) in Metro Manila, facing down the troops deployed against them. Portions of the military began to defect. Finally, on February 25, opposition leaders swore in Corazon “Cory” Aquino, Ninoy’s widow, as president. Marcos fled to Hawaii the following day.

Thousands of protesters filling Epifanio de los Santos Avenue in 1986 (left). Corazon “Cory” Aquino swearing in as President of the Philippines in 1986 (right).

The last week of February became a holiday, a commemoration of the EDSA (or People Power) Revolution and the return to democracy. The EDSA Revolution established the parameters for mainstream politics, with subsequent leaders paying rhetorical homage and participating in elaborate ceremonies. By 2010, the presidency was in the hands of Benigno Aquino III, son of Ninoy and Cory. He left office in June 2016 with a performance approval of 57%, the best of any post-EDSA administration.

Then came Rodrigo Duterte.

In February 2017, his administration moved the EDSA commemoration from the street to a military compound. Skipping the ceremony, Duterte spent the week in Davao, where he had served as mayor for 22 years. The implications of these actions were clear. As Duterte mused in his public message, “Thirty-one years have swiftly passed … and perhaps, now is the opportune time to ask ourselves—what have we achieved after EDSA?”

By then, Duterte’s vaunted drug war was in full swing. The first six months claimed an estimated 6,000 lives, many in extra-judicial murders. Duterte was and remains unapologetic in the face of international criticism. When American officials questioned the killings, he called the U.S. ambassador a “gay son of a bitch,” and later appeared to lob a similar insult at President Barack Obama. He threatened to leave the United Nations, and when the International Criminal Court began an investigation, he withdrew the Philippines from that body.

There were prominent critics within Duterte’s own country, as well. Archbishop Socrates Villegas, president of the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines, issued a scathing statement at the beginning of the 2017 EDSA commemoration. In comments clearly aimed at Duterte, he denounced the “rape” of the Revolution.

Yet Duterte’s performance approval stood at 86%, his disapproval at 3%. These numbers held well into his presidency, baffling his critics.

The Philippines is one of several countries that has recently seen an upending of the political consensus. While diverse, these movements are generally defined by their “populist” character, driven by views of a pure “people” set against a corrupt, subversive “elite.” Spite for the perceived establishment is a powerful motivator, but as author John Judis recently suggested, populist movements “point to tears in the fabric of accepted political wisdom.” When the mainstream parties overlook a widespread concern, a populist challenge is born.

Many elements of “Dutertismo” fit this model.

Supporters of President Duterte on the National Day of Protest in 2017.

Here was an audacious, profanity-spewing candidate whose shock value grabbed attention and, in some quarters, seemed refreshing when compared to traditional politicians. He held up a serious social problem—drugs—as an emblem of the establishment’s failures, then promised to fix it by hook or crook. When detractors found him wanting against international standards, he blasted them for hypocrisy.

To understand Duterte’s connections to Philippine history, one can take up his pointed question: What had happened since the EDSA Revolution 30 years ago?

After Marcos fled, elite families—including Cory Aquino’s—jockeyed to reestablish their positions. The age-old problems of corruption and extreme poverty persisted, and Aquino offered no new solutions. Several allies turned against her, and there were multiple attempted coups. When economic growth did begin to return, it largely benefited the urban middle class.

Subsequent events even called into question the democratic foundations of the EDSA consensus. In 2001, after president Joseph Estrada survived an impeachment proceeding, demonstrations backed by Aquino, her allies, and the military forced him out of office. Termed “ EDSA II ” by supporters, it was the extralegal removal of an elected president. Estrada’s successor won reelection in 2004 amid accusations of flagrant voter fraud.

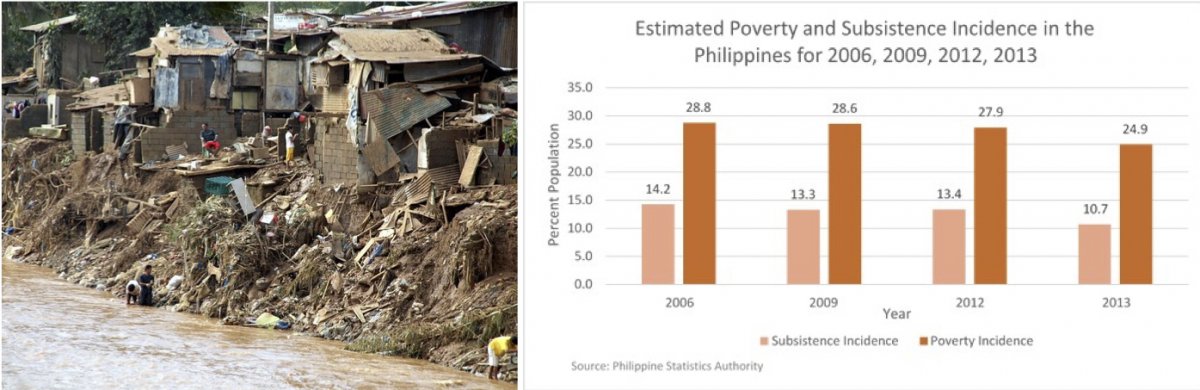

A poor neighborhood in Manila during flooding in 2009 (left). A graph depicting the percent of the Filipino population at poverty and subsistence levels in 2006, 2009, 2012, and 2013 (right).

By the time Cory’s son held the presidency (2010-2016), the same economic problems persisted. He boasted of a robust 6% annual growth rate, but as historian Alfred W. McCoy notes, 40 families controlled 76% of the growth while a quarter of the population lived on a dollar a day.

Enter Duterte, a mayor from the far end of the country, with no visible ties to a Manila cabal. In addition to the drug war, he advocated for the 2.2 million Filipinos laboring abroad. After Super-typhoon Haiyan slammed into Leyte and Samar Islands in November 2013, then-Mayor Duterte visited within days and coordinated his own aid effort, while President Aquino took the blame for a poor national response. Well into Duterte’s presidency, disaster aid and protection of overseas workers were his top two performance ratings, just ahead of “fighting criminality.”

President Duterte with volunteers aiding survivors of super typhoon Haiyan in 2013 (left) and visiting Filipinos living in Vietnam in 2016 (right).

Duterte, clearly, had found “tears in the fabric of political wisdom.” He had said as much in the final presidential debate: “if you just listen to my epithets, my curses and my—you know, bad words—look at my back, for you’ll see there the Filipino on bended knees, hungry and very mad at this country for doing nothing.”

Perhaps his daughter, firing back at the archbishop’s “rape” comments, encapsulated the sentiment the best: “I find it hard to understand why [the EDSA] revolution has become the definition of freedom for our country and this standard is forced down our throats by a certain group of individuals who think they are better than everyone else.”

To cement the repudiation of EDSA, the newly-elected Duterte even reburied Marcos, the deposed dictator, in the nation’s “Heroes’ Cemetery.” He also implemented a style of governance that the former president might have recognized.

Protesters of the Supreme Court’s 2016 decision to bury the late president and dictator Ferdinand Marcos in the Heroes Cemetery near Manila (left). The former Chief Justice Maria Lourdes Sereno speaking with supporters after Duterte ousted her from office in 2018 (right).

In his first year, Duterte attained a sevenfold increase in the budget of the Office of the President. He banned the vice president—elected separately—from cabinet meetings, and his supporters helped bring about the arrest of a senate critic and the removal of the chief justice. When an ISIS-affiliated group seized a town in the southern Philippines, Duterte became the first president since Marcos to impose martial law.

These events lead one to wonder: if the current brand of Philippine populism rests on a rejection of EDSA’s failings, to what extent does the movement accept EDSA’s purpose, the overthrow of authoritarian rule?

The opinions, views, and conclusions expressed or implied in this paper are solely those of the author and do not represent the views of the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Hungary: Viktor Orbán’s Brave New Authoritarian Populism

by Zoltán Ádám

Let’s face it: we all have a little Duterte, Orbán, or Trump inside us. We all want our family, home, and country to be safe and to operate smoothly. And we all want this now, not tomorrow. We are all fed up with democratic deliberation, muddling through, and self-serving political show-offs cheating on principles. Politicians are all the same, no exceptions.

Unless these three politicians (and the many others like them) are exceptions. If they are different, they possess something the famed sociologist Max Weber called charisma a century ago.

In Weber’s classic treatment, a charismatic leader “derives his authority not from an established order and enactments, as if it were an official competence, and not from custom or feudal fealty, as under patrimonialism. He gains and retains it solely by proving his powers in practice. He must work miracles, if he wants to be a prophet. He must perform heroic deeds, if he wants to be a warlord. Most of all, his divine mission must prove itself by bringing wellbeing to his faithful followers; if they do not fare well, he obviously is not the god-sent master.”

Viktor Orbán of Hungary seems to have read Weber pretty well on this.

Orbán has not come from nowhere. He has been around for 30 years. Born in 1963 and trained as a lawyer, he appeared on the central stage of Hungarian politics in 1988, a year before the regime change started. He was one of the leaders of Fidesz (the Latin word for fidelity and a Hungarian abbreviation for young democrats at the same time)—a young, liberal political party defining itself in opposition to the ruling Communists.

In June 1989, he delivered a fiery anti-Communist and anti-Soviet speech at the reburial of Imre Nagy, the martyr prime minister of the 1956 revolution. In 1990, he was the parliamentary leader of Fidesz, by then in opposition to the democratically-elected center-right government. But by 1994, Fidesz itself was in the center-right, this time in opposition to the democratically elected center-left, and Orbán had started his long march from being Hungary’s most promising young liberal democratic leader to the destroyer of Hungarian liberal democracy.

Why did a talented and popular young liberal democrat turn into a talented and popular autocrat he himself would have mocked and ridiculed 30 years ago? Because he was too good a politician not to do it.

As early as the mid-1990s, Orbán already recognized a growing discontent with liberal democracy in Hungary, especially on the political right that has always been opposed to openness and liberalism. He also knew that he could replace the old guard at the helm of the right and strengthen the anti-liberal camp.

Conditions were ripe. Hungary did not have much of a democratic tradition, and throughout the 20thcentury it kept losing on the deals of western liberal powers. To a large extent in response to the hostile Trianon Treaty of 1920, it was an ally of Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany in the interwar period, then occupied by the Soviets in 1945, and left at their mercy in 1956 by the United States and its western allies during the failed uprising.

A Hungarian poster against the Trianon Treaty from 1920 (left). Hungarian Jews being arrested in Budapest during Nazi occupation in 1944 (top right). A destroyed Soviet tank in Budapest during the 1956 Revolution (bottom right).

Even more importantly, however, unlike in Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Poland, or Romania, democracy was never really popularly pursued in Hungary before the regime change. Although there had been an important and heroic opposition movement—the so-called Democratic Opposition—it did not turn itself into a popular movement before 1989, when the Communist regime was already collapsing and was prepared for a compromise with the new opposition groupings.

At the same time, the Kádár regime (named after János Kádár, the Communist leader of Hungary between 1956 and 1988) was an increasingly populist dictatorship, politically liberalizing while fiscally overspending to avoid social conflict.

János Kádár visiting schoolchildren in Budapest in 1985.

In consequence, Hungary became one of the most indebted Communist countries in the 1980s, with—it soon turned out—only modest international economic competitiveness. The economic transition in the 1990s eliminated about 1 million jobs (roughly 20% of the labor force) and created a large block of voters relying on fiscal transfers. Serving their needs at consecutive elections since the end of the first transition decade, the pattern of fiscal populism was reinforced and Hungary once again started to spend beyond its means.

When fiscal stabilization could no longer be postponed, the center-left government of 2006-2010 started an austerity program, exacerbated by the 2008 global financial crisis. In response, Orbán won big at an anti-reform/anti-government referendum in 2008, at the European Parliamentary elections in 2009, and the national parliamentary elections in 2010. Due to the heavy bias of the electoral system towards the strongest party because of the dominance of individual electoral districts, Orbán gained a two-third parliamentary majority in 2010. With this mandate he could change any piece of legislation.

Orbán addressing crowds of supporters in 2012.

And, of course, he did. Fidesz altered the constitution and made the electoral system even more biased towards the winner. He centralized political, cultural, and economic power across the board. This was done quite efficiently: the opposition has remained weak and fragmented ever since, and Fidesz won two-thirds majorities in the following two elections.

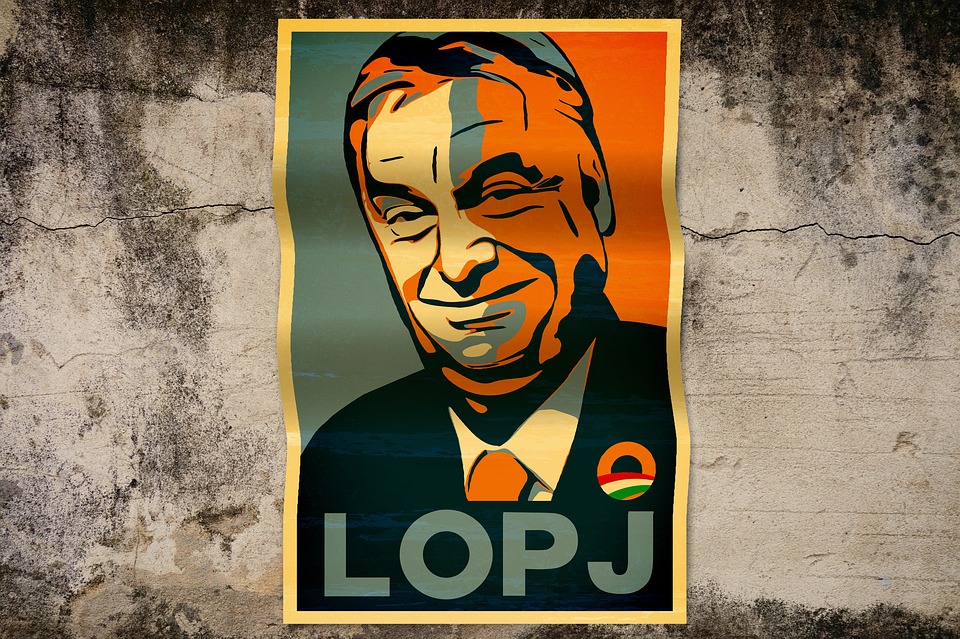

To be clear, these were not free and fair elections. The government spent hundreds of millions of taxpayer dollars on advertising campaigns, conjuring an atmosphere of hatred and fear.

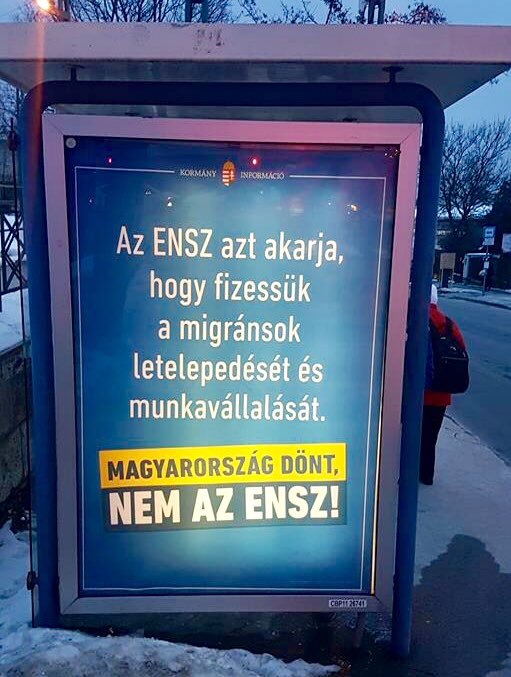

These included election campaigns, “national consultation” campaigns, and a referendum campaign. Government ads denigrated the EU, George Soros, and even the United Nations for its stance on refugees. In a truly Orwellian fashion, government-paid billboards declared that ‘Hungary decides, not the UN!’ In another campaign, billboards read “The Hungarian reforms are working!”

In addition, the new election system created a pool of extraterritorial voters whose vote count was not transparent, but was enough to provide Fidesz with an additional member of parliament—exactly on whom the two-third majority depended both in 2014 and 2018.

Hence, by western standards, Hungary was no longer a democracy. Yet it provides popular legitimation and reproduces power in a centrally and hierarchically controlled way one can call authoritarian populism.

Orbán has been lucky. The period of fiscal stabilization and economic crisis ended in 2013. Since then, the economy has been steadily growing. An important growth factor and a source of politically administered rents is the steady flow of development funds from the EU that constitute in the range of 2 to 4% of GDP annually—in magnitude comparable to the post-WWII Marshall Plan.

But Orbán has also changed the structure of redistribution: he cut middle class taxes, raised the tax burden of the lowest income brackets, and reduced social benefits. He expanded public work programs and, with the assistance of the central bank, offered cheap credit to companies. With demand for labor rising in Western Europe, the out-flow of Hungarians has meant that unemployment has essentially disappeared.

He also cut the statutory profit tax rate but levied special taxes on industries dominated by foreign businesses, such as banking, telecommunications, retail sales, and utilities. Large multinationals in these industries have been taxed, and some of them have been persuaded to sell their businesses to Hungarians, especially to the government itself. This way, state ownership has increased in banking and utilities, while private Hungarian firms have enjoyed preferential market access in various industries.

Meanwhile the media market has been firmly controlled by the government, through public media, government advertisements, preferential loans, distribution of frequencies, and custom-suited regulation. There are no more politically neutral government agencies as the Fidesz-controlled parliament has appointed Fidesz-friendly heads to steer all of them. The independence of the court system has been attacked through restructuring, early retirement of older judges, as well as sheer political pressure. Human rights NGOs are treated as enemies, considered the fifth column of public enemy No. 1 George Soros, who has been ritually abused by government propaganda.

Syrian refugees during a 2015 hunger strike in Budapest to protest Hungary closing its borders with Serbia and forcing refugees into camps (left and right).

Finally, the migration crisis and Orbán’s refusal to receive a single refugee within the EU’s quota-based refugee scheme, despite his acceptance of EU subsidies, only made him appear more of a hero in his camp. This stance has helped spread his influence across the EU. Since 2015, Orbán has posed as the European commander-in-chief of this war, and he now has a significant following across Central Europe (the Czech Republic, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia) as well as in Austria, Bavaria, and Italy.

The anti-migrant card for Orbán is like the wall on the Mexican border and the tariffs on foreign goods for Trump. It demonstrates his determination to protect his nation against its foreign enemies seeking to undermine its identity, integrity, and sovereignty.

In blatant conflict with international conventions and EU law, unreasonably harsh measures and brutal force are being used against irregular migrants and refugees. They are employed as scapegoats to demonstrate the toughness and wickedness of a regime pretending to be a democracy but wishing to intimidate anybody opposing it.

President Vladimir Putin and Orbán during a 2015 meeting in Hungary.

This is perhaps the nastiest aspect of Orbán’s brave new authoritarian populism: his charisma is being exercised against the weakest and most defenseless, who are least able to stand up against him.

In short, over the past eight years, Hungary has turned into a formally democratic yet essentially autocratic regime, peacefully existing in the middle of Europe, enjoying EU membership, and hovering around the brink of outright authoritarianism.

Check out a lesson plan based on this article: The Rise of New Populism

Ágh, Attila (2016): “The Decline of Democracy in East-Central Europe. Hungary as the Worst-Case Scenario.” Problems of Post-Communism, Vol. 63, No. 5-6, pp. 277-287. DOI: 10.1080/10758216.2015.1113383

Ádám, Zoltán – András Bozóki (2016): “’The God of Hungarians’. Religion and Right Wing Populism in Hungary.” In: Nadia Marzouki, Duncan McDonnell and Olivier Roy (eds): Saving the People. How Populist Hijack religion.Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Brubaker, Rogers (2017). “Between nationalism and civilizationism: The European populist moment in comparative perspective.” Ethnic and Racial Studies, Vol. 40, No. 8, pp. 1191-1226.

Carter, Dan. The Politics of Rage: George Wallace, the Origins of the New Conservatism, and the Transformation of American Politics (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995).

Curato, Nicole, ed. A Duterte Reader: Critical Essays on Rodrigo Duterte’s Early Presidency. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2017.

Enyedi, Zsolt (2016): “Paternalist populism and illiberal elitism in Central Europe”. Journal of Political Ideologies, Vol. 21, No.1, pp. 9-25. DOI: 10.1080/13569317.2016.1105402

Hamilton-Paterson, James. America’s Boy: A Century of Colonialism in the Philippines. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1998.

Judis, John. The Populist Explosion: How the Great Recession Transformed American and European Politics. New York: Columbia Global Reports, 2016.

Kazin, Michael. The Populist Persuasion: An American History, 2nd ed. (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2017).

Kornai, János (2015). “Hungary’s U-turn: Retreating from democracy,” Journal of Democracy, Vol. 26, No. 3, pp. 34–48. Full version: www.kornai-janos.hu.

Mendelberg, Tali. The Race Card: Campaign Strategy, Implicit Messages, and the Norm of Equality (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017).

Mudde, Cas – Cristobal Rovira Kaltwasser (2017). Populism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Müller, Jan-Werner. What is Populism? (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016).

Pappas, Takis (2014). “Populist Democracies: Post-Authoritarian Greece and Post-Communist Hungary.” Government and Opposition, Vol. 49, No. 1, pp. 1-23.