If one photograph has captured the magnitude and sadness of the 2015 refugee crisis, it is the boy on the beach: three-year-old Alan Kurdi, found drowned and washed up near the Turkish town of Bodrum after the overcrowded boat carrying him and his mother and brother across the Mediterranean was overcome by waves. They were just three of more than a million migrants who fled war-torn and destabilized parts of the Middle East and Africa in 2015, trying desperately to find refuge in Europe. Many commentators now call this “one of the greatest humanitarian crises the globe has ever known.” This month, historian Theodora Dragostinova explores the causes and pathways of today’s refugee crisis and reminds us that displacement and migration have long defined European history.

Read these insightful Origins articles for more on migration around the world: Global Migration and the Americas; U.S. Immigration Policy; and Operation Wetback

Listen to these History Talk podcasts on Road to Europe: The 2015 Migration Crisis and the Syrian Civil War and Arab Spring.

Over the past months, politicians, journalists, and ordinary people across Europe have passionately debated what is variably called the refugee or migrant crisis in Europe. Some have used expressions such as “flood,” “invasion,” or “swarms of people” to describe the hundreds of thousands who are determined to reach Europe in search of security and stability.

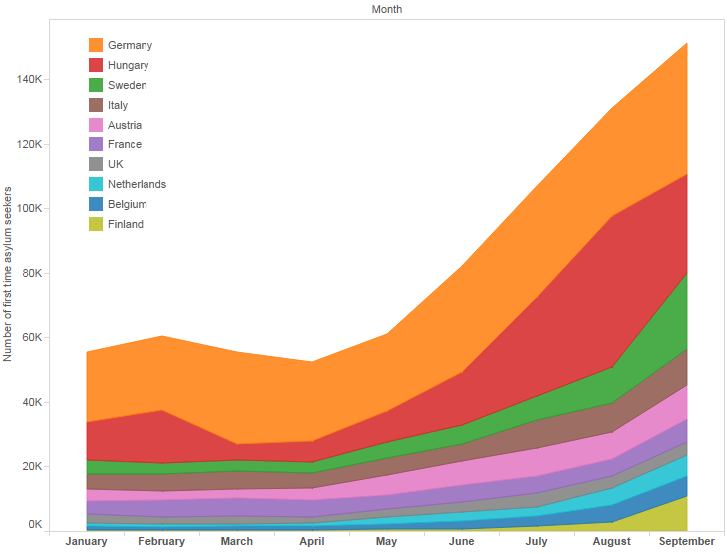

With close to one million people arriving in 2015, many Europeans worry about the integration of these new populations.

They raise concerns that the migrants would require extensive state support in a time of continued economic insecurity in Europe. Some Europeans also fear that they would threaten the cultural makeup of Europe due to the alleged incompatibility of the Islamic faith of the majority of new arrivals.

Anti-refugee graffiti. Ljubljana, Slovenia, September 2015. Photo by M.A. Johnson |

The migration crisis has spread images of suffering, courage, and intolerance. It has strained the unity of the European Union, sparked debate about the difference between Western and Eastern Europe, and posed difficult questions about global inequality.

While these developments have often been portrayed as an unprecedented crisis, this is certainly not the first time that Europe has faced such challenges.

During the 20th century, Europe saw some of the largest waves of refugees and most violent forced migrations in human history, especially as a result of the First and Second World Wars. Some of these forced migrations can be more accurately described as ethnic cleansing and, in the case of the removal and ultimate extermination of Jews from Europe, genocide.

|

And Europe has long been a popular destination in global migration flows. Traditionally, the Mediterranean has functioned as the main route for migrants from Africa or the Middle East into Europe. This is perhaps one of the oldest routes of contact in human history, going back to the Iron Age and the great empires of antiquity.

During the age of European imperialism, networks grew from the colonial relationship between Africa and Europe. Especially since postwar decolonization, migrants have been drawn to the former metropoles because they know the language or rely on diasporic networks.

In the 21st century, as conflicts in Africa mounted (in Eritrea, Libya, and Sudan, to name a few), the number of migrants crossing the Mediterranean soared. Traffickers ruthlessly exploited the vulnerability of these desperate individuals fleeing both persecution and poverty.

Distinguishing between political migrants (those trying to escape persecution) and economic immigrants (those moving from poverty) is difficult but important because international law treats these two categories of people differently.

The 1951 United Nations Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, ratified by all European states, defined a refugee as someone who “owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality, and is unable to, or owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country.”

Rescued migrants arriving in Italy, June 2015 (left). Migrants walking through Hungary on their way to Austria, September 2015 (right).

International law guarantees to each person fleeing persecution the right to request asylum in a safe country. The authorities reviewing people’s asylum applications determine whether one is a refugee or an immigrant on a case-by-case basis.

Asylum laws differ in each European state because the EU considers immigration law a matter of national sovereignty. Generally, those who are found not to qualify for asylum as refugees are deported to their country of origin. The uncertainty of the process explains why many people do not even file for asylum, but continue to live in the shadows as undocumented migrants.

Those who succeed in staying in Europe generally take unskilled jobs that the local population does not desire. In this way, they tend to fill crucial labor needs for the host society.

As we look to the future of today’s migration wave to Europe, we need to recognize that the issue of global human migrations may very well define the 21st century.

As globalization has become the rule, and as the West has generally benefitted disproportionately from the economic integration entailed in this global process, it cannot simply ignore the fact that people will continue to cross borders in search of better life, a basic human right.

And, if we return to the claims that today’s migrant crisis is an “invasion,” we see that instead of “flooding” and “besieging” Europe, these migrants and refugees tend to flee for a reason (armed conflicts or economic distress), follow pre-established political and social networks (of empire and diasporic communities), and occupy employment niches that are undesired by the locals (rather than “take our jobs”).

Migration is a highly structured process built upon patterns, historical contexts, and rational individual decisions. And integration is a long-term, complex process that takes generations and requires accommodation between the new arrivals and the host society.

What Triggered the Refugee Crisis in Summer 2015?

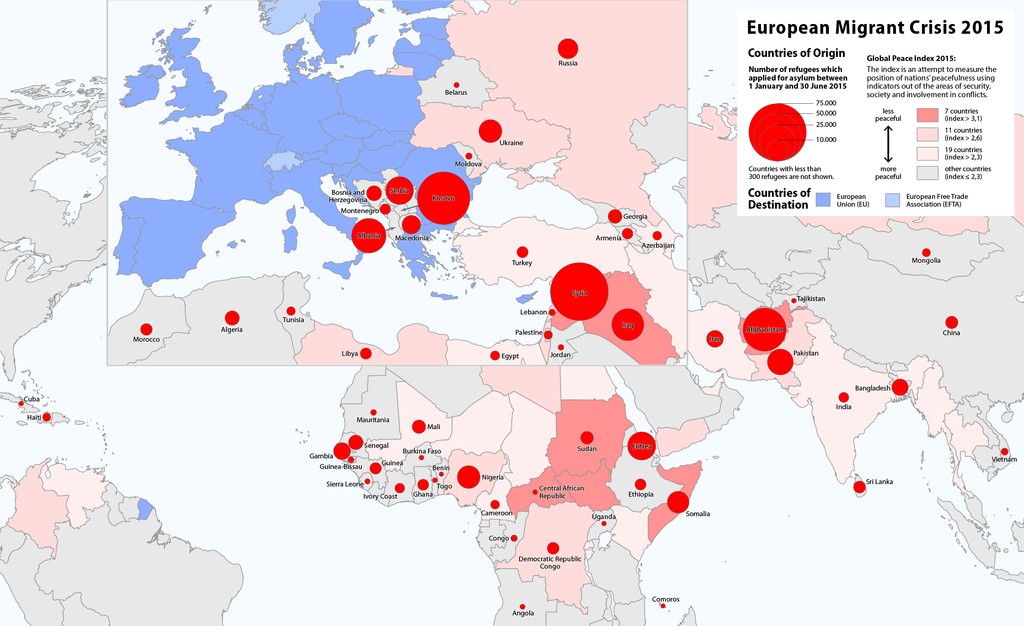

The immediate cause of the current crisis is the ongoing civil war in Syria over the past four years, which has left 22 million Syrians incredibly vulnerable. This situation is compounded by the breakdown of authority in Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, and Eritrea. As a result, desperate people started fleeing in even larger numbers during the past two years.

|

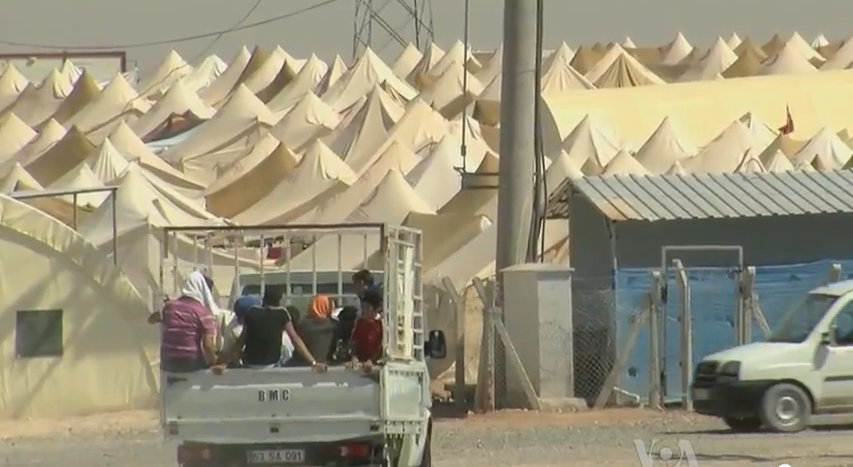

For a few years now, the Syrian refugees have been mainly going to neighboring Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey, hoping that with the end of the civil war in Syria, they will be able to go back home. Many live in refugee camps funded by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) or, once registered as refugees with the UN, subsist on meager stipends in the larger cities of those three countries.

The UNHCR has registered more than 4.1 million Syrian refugees; more than 1 million reside in Lebanon, a country with a population of 4.5 million, and more than 2 million reside in Turkey.

But as the Syrian conflict intensified in 2014 and 2015, and as the refugees were generally unable to find lawful employment and decent housing or establish permanent legal residence in Lebanon, Jordan, or Turkey, they started evaluating other options. Because the Gulf Arab states did not accept these refugees, Europe emerged as the only other possible destination.

|

From Turkey, Bulgaria is the closest European entry point – a two-hour trip by car or bus from Istanbul. There, arrivals can apply for asylum in this EU member state or continue to another country.

Syrian refugees generally do not want to stay in Bulgaria, a country of 7.5 million, although some 15,000 have registered as refugees there. While asylum applications in Bulgaria have a striking success rate of 94 percent, very few actually desire to settle in this poorest EU member state, where they face decrepit, underequipped transit centers and refugee camps.

An even more powerful deterrent preventing human movement from Turkey to Bulgaria is the fact that, two years ago, the Bulgarian government started building a barbed wire fence, with the alleged goal of stopping human traffickers from Turkey. This fence was built with striking efficiency, despite the lack of funds in the country for more urgent infrastructural projects.

It is because of the risk of this impenetrable Bulgarian fence that refugees risk drowning in the Mediterranean on rickety boats from Izmir, Turkey, to the nearby Greek islands of Lesvos, Kos, and Rhodos.

|

Yet most refugees attempt to leave Greece soon after arrival because of the 25% unemployment rate (50% for young people) and scarce economic resources as well as restrictive citizenship and residence laws.

The Balkans and East-Central Europe in the Spotlight

Most of the new refugees arriving in Greece want to go to Germany, Austria, Sweden, or Norway, western European states with liberal migration policies and generous social benefits.

But to arrive there, they must cross a series of impoverished, conflict-ridden states in the “Western Balkans”—as Albania together with the non-EU-members of the former Yugoslavia (PDF File) (Macedonia, Kosovo, Bosnia, and Serbia) tend to be called.

Over the summer, there were chaotic scenes of refugees waiting at train stations in Macedonia or sleeping in tents in downtown Belgrade, Serbia. There was a standoff between Croatia and Serbia on the issue of refugees, reminding us that the wounds of the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s are still present. When crossing into Croatia, the refugees face the terrifying possibility of running into undetonated mines from the wars.

This dramatic situation has highlighted the ultimate failure of the European project at the margins of Europe, in the Balkans. While Croatia, Slovenia, Bulgaria, and Romania are now EU members, EU accession talks with Serbia, Bosnia, Macedonia, Albania, and Kosovo are in limbo.

The Western Balkans has now become a European ghetto, a series of marginalized states whose citizens have little hope for the future besides emigration to the West.

It is clear that migrants from Kosovo, Albania, and Bosnia, most notably, have joined the recent refugees from Syria and Iraq in their march to Austria and Germany. This development has prompted Germany to declare the Western Balkans a “safe area” and announce that it would automatically deport all asylum seekers from those countries.

|

But the Syrian and other recent refugees are not faring better in the rest of the Eastern European states that are now EU members: Croatia, Slovenia, Romania, Hungary, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, and Poland.

The situation is most dramatic in Hungary, where Prime Minister Victor Orban, a leader of the far-right nationalist party Fidesz, has adopted an uncompromising anti-refugee position. Hungary emerged as a desired destination for the refugees because it is a member of the so-called Schengen zone that does not require passport controls and border posts between member countries.

As a result, the human flow has been redirected to Slovenia, a small country of barely 2 million, whose government has had to deal with as many as 15,000 refugees crossing into the country daily. Its government threated to close off its border should Austria and Germany not speed up the transfer of refugees along the way.

To stop the human flow, however, over the summer of 2015 the Orban government completed a 15-foot barbed wire fence on its border with Serbia; even more controversially, the government finished building a fence on the border between Hungary and Croatia, another EU member state.

Striking refugees at a railway station in Budapest, Hungary, September 2015 (left). Border fence between Hungary and Serbia, 2015 (right).

Ironically, leaders of other East-Central European states – which have not been affected by the crisis as profoundly as the Balkans – have made regrettable choices on the refugee topic.

Slovak leaders have indicated that Muslims would not be welcome in their country and have only reluctantly agreed to accept a limited number of Christians. In the Czech Republic, photographs of police writing numbers on refugees’ arms with permanent markers have prompted comparisons to the Holocaust.

In this context, an old question has been raised again: Is Eastern Europe somehow more xenophobic that the rest of Europe? Are the former Soviet bloc countries unable or less willing to cope with ethnic, linguistic, and religious differences?

No conclusive studies compare Eastern and Western European attitudes toward foreigners. But there has been a resurgence of far-right parties, supporting anti-immigrants agendas, in many Western European states as well, including France and the Netherlands.

The standoff between France and Britain over 2,000 immigrants on the French side of the Channel Tunnel – who are living in miserable conditions in a makeshift camp described as “the jungle” – indicates a similar unwillingness of Western European politicians to engage the issue of migration constructively.

A more relevant question might be: Do East-Central and Southeastern Europe need to receive more help from the rest of Europe? Given the much lower standards of living in many of those countries compared to the rest of the EU, how much responsibility should they be asked to take in the current crisis? Should this instead be a European (i.e. EU) responsibility?

Europe’s Long Experience with War, Persecution, and Refugees

The current refugee crisis is but one moment in the much longer history of refugees, immigrants, and displaced persons in Europe.

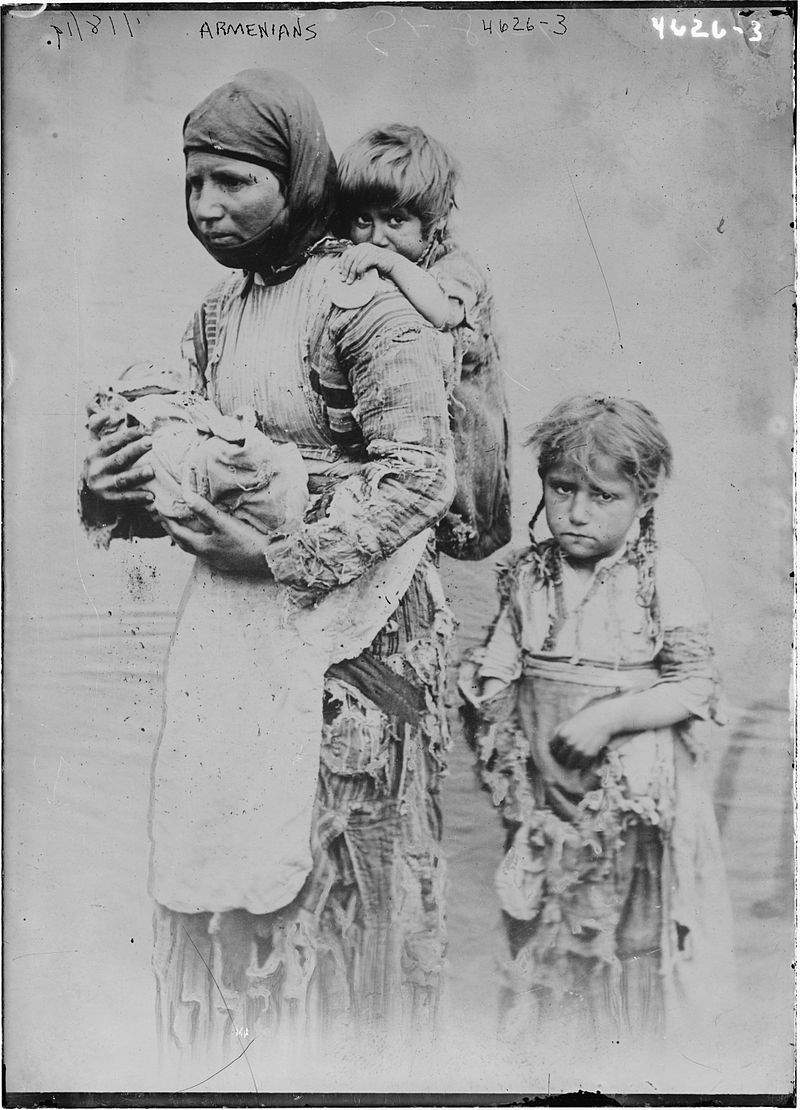

The traumatic experiences of forced migration mark the beginning of the 20th century in European history. As a result of the Balkan Wars (1912-1913) and World War I (1914-1918), the entire region of Eastern Europe saw a flood of millions of refugees.

|

In the Balkans, especially on the Bulgarian-Turkish-Greek-Serbian borders, fighting in some areas lasted as long as six years, from 1912 to 1918. As the borders and military and civilian administrations changed multiple times, people fled their villages as control of their land switched hands. Each border change was accompanied by the movement of people.

Bulgaria, for example, had to accommodate some 280,000 wartime refugees in the 1920s, and their integration into Bulgarian society was not always smooth.

In the case of what is now often referred to as East-Central Europe, in the borderlands between Russia, Germany, and Austria where much of the fighting on the eastern front took place during World War I, the size of the refugee movements (6 million people) motivated one historian to describe the situation there as “a whole empire walking.”

Continuing conflict between Turkey and Greece about Asia Minor led to the massacres of both Christians and Muslims at the hands of the rival army during the Greco-Turkish war of 1920-1922.

With the destruction of the thriving port of Smyrna/Izmir—ironically the point of departure today for many desperate Syrian refugees—Greece and Turkey enacted the first compulsory population exchange in history, agreed upon with the mediation of the League of Nations in 1923. Some 2 million people, Christians and Muslims alike, were affected by this treaty, which uprooted people from their homes without giving them any other choice.

The dynamics of that humanitarian tragedy bear a striking resemblance to what is happening in the area today. Despite the intervention of the League of Nations, the integration of 2 million refugees put severe pressures on Greek and Turkish societies and economies. It was only with the third generation that these “newcomers” finally felt at home.

European Refugees in the 1930s and 1940s

Further predicaments over the status of refugees in Europe emerged after 1933 when Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany. In 1933 alone, close to 50,000 of the approximately 500,000 German Jews tried to leave Germany, but European governments carefully controlled the entry of “foreigners” into their states.

In their desperation, Jews who were unable to secure papers for emigration to other parts of Europe, the first choice, or Palestine (then a British mandate), the increasingly preferred option, considered various resettlement schemes in the United States, Central and South America, Africa, and China.

During this time, western European states carefully refined their increasingly restrictive systems of passport and border control. Participants at the 1938 Evian Conference refused to deal decisively with the crisis, rationalizing that accepting more Jewish refugees would only encourage the Nazi regime. To alleviate guilt, the British accepted 10,000 Jewish children who arrived through the privately funded Kindertransport program.

By 1941, about 160,000 Jews remained in Germany. Unable to flee, the vast majority were killed during the Holocaust.

During World War II, even larger-scale population movements led to the ultimate ethnic homogenization of the European continent. The combined number of wartime and postwar forced migration in Europe is close to 64 million people. Many of these people fled military conflict as the war spread. Most of them later sought to return to the areas they had fled.

This number includes the 6 million Jews exterminated by the Nazi regime, a powerful reminder that when the world does not act, enormous human tragedies can occur.

|

At the end of the war, the postwar winners enacted another massive forced migration, the removal of all German populations from neighboring countries, some 13 to 14 million people who “went home” to Germany from Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Yugoslavia, and elsewhere. Poles and Ukrainians were two other large groups that were subjected to forceful population swaps in the name of national homogeneity.

As a result of these forced migrations, the European continent had been re-made into largely ethnically homogeneous states that had efficiently purged their territories of undesired ethnic or religious minorities.

This homogeneity, which some in Europe fear will be lost with the current influx of new people, was the outcome of a series of violent and relatively recent historical episodes.

Across the Iron Curtain: A Cold War Divergence between East and West

During the Cold War, the two parts of Europe took diverging paths regarding population movement and migration.

Western Europe became more religiously and ethnically diverse with the influx of a large number of guest laborers from Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, some of them from former colonies. While invited to help rebuild Europe as temporary migrants, many stayed, contributing to the transformation of western European countries into multiethnic societies.

Some of the most visible immigrant communities include the Turks in Germany, the Algerians in France, and the Indians and Pakistanis in Great Britain. Since 2013, the majority of London’s population is people of color.

Migrants waiting to enter Germany, October 2015 (left). Pakistani shops and restaurants on Wilmslow Road in Manchester, England, nicknamed "The Curry Mile" (right).

By contrast, Eastern Europe, especially East-Central Europe, remained ethnically homogeneous in the postwar period. Today, many politicians continue to talk about their countries as homogeneous national spaces with no prior experiences of religious or ethnic diversity. This is simply wrong and ignores the history of the region merely 70 years ago.

There were exceptions, such as Bulgaria and Romania, which continued to have large minorities in their territories. These minorities were periodically subjected to nationalist pressure; some 350,000 Turks fled Bulgaria in the 1980s in what was at the time described as “the largest refugee wave after World War II.”

Nonetheless, the Soviet bloc countries maintained regimes of closed borders and limited travel opportunities for their citizens. Built in 1961, the Berlin Wall became the symbol of this separation between East and West, a potent metaphor of captivity.

It is not coincidental that the end of the Cold War began with the mass exodus of East Germans to the West in the summer of 1989 following the removal by Hungarians of barbed wire fences between Austria and Hungary. In effect, in 1989 Eastern Europeans rebelled, among other things, against the regime of closed borders and travel controls.

It is therefore beyond ironic that the current government of Hungary, the country that started removing fences in 1989, is building a new barbed wire fence in unified Europe today.

But the end of the Cold War did not bring peace and security to Europe. The Yugoslav Wars of the 1990s (PDF File) saw what was then termed (again) “the largest forced migrations in Europe after World War II” with some 2.7 million Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) and refugees.

Many of these Yugoslav war refugees were offered “temporary humanitarian shelter” elsewhere in Europe under circumstances that resemble today’s plight of the Syrian refugees. Many returned to Bosnia and other formerly Yugoslav areas after the war, but still others permanently resettled to Western Europe and the United States.

In another parallel to today, Germany and Austria accepted the largest number of Yugoslav refugees in the 1990s.

From Past and Present to Future

Given these complex past experiences with migration, what lessons can history teach us about the refugee crisis in Europe today?

In the face of a prolonged and brutal conflict, people will seek to flee. If they don’t flee, conflict may escalate into ethnic cleansing and even genocide. This is particularly so in cases of civil war, such as the Syrian conflict.

After the devastating experience of the Holocaust, it is difficult to deny that we need to help people fleeing persecution and war. The sanctity of human life should come first.

But is the current refugee crisis of unprecedented proportion?

|

Historical research shows that migrants are always a small part of the overall population. Within the EU, whose population nears 750 million in 2015, the presence of even one million refugees remains a relatively insignificant number.

Furthermore, the UNHCR estimates there are close to 60 million displaced persons globally in 2014. The one million who reach Europe, one of the most prosperous places worldwide, therefore, is just a drop in the global bucket.

But how do we decide who is a refugee and who an immigrant? Some people are both; other people constantly transition between the two categories. This determination should be made in each individual case, but officials should err on the side of caution because the overlap between poverty and conflict in today’s world is rampant.

Would people return to their countries after the end of conflict? Historical evidence suggests that there are always a large number of people who want to return to their places of birth.

Migration waves are usually temporary. The current refugee crisis will most likely level off with the arrival of winter when fewer people will dare to cross the Mediterranean.

While it is difficult to predict what will happen in the Middle East, in the long term the pacification of Syria could trigger a large migration back to it. Unfortunately, in this case, that scenario is not imminently likely.

Gender dynamics are an important factor in migration. Historically, young men seeking to avoid military conscription are the first to depart. Often, they send money home and attempt to reunite their families.

Yet during war, large numbers of women and children travel alone, and these are the most vulnerable migrants.

We need to pay attention to how men and women experience migration differently. Ideally, families should stay together. There should be active policies to prevent sexual violence against women, which is widespread in such fragile situations.

Children waiting to be evacuated from Spain during the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939 (left). Syrian refugees in Ramtha, Jordan, August 2013 (right).

Many Syrian refugees go to Europe because they already have family members in European countries who have settled there and are able to assist them. In effect, these are “chain migrations” of mostly middle-class, educated, and motivated refugees, which could reinvigorate the labor force of Europe. We also need to remember the importance of social class in migration decisions. More affluent individuals are better able to finance their journeys and acquire the needed documents. This is the case with many of the Syrian refugees.

Yet, integration is a long-term process that depends on the willingness of both the newcomers and the host society to live together. The first generation is often grateful to be given the opportunity to start a new life, so the crucial question is how to make sure the second generation is not marginalized.

Based on past experiences, European societies should pursue integration along several lines: immediate language training and civics education, psychological counseling for those who need it, schools for children, employment for adults, housing that does not segregate, and wider debates in society over the meaning of integration.

In this process, Europeans will have to learn to live together with their new neighbors on pluralistic rather than assimilationist principles.

Bade, Klaus. Migration in European History, Blackwell, 2003.

Clark, Bruce. Twice a Stranger: The Forced Migrations that Forged Modern Greece and Turkey. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007.

Dwork, Deborah and Robert Jan van Pelt, Flight from the Reich. New York: Norton, 2012.

Gatrell, Peter. A Whole Empire Walking: Refugees in Russia during World War I. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005.

Geddes, Andrew. The Politics of Migration and Immigration in Europe. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications, 2003.

Lucassen, Leo. The Immigrant Threat: The Integration of Old and New Migrants in Western Europe since 1850. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2005.

Marrus, Michael. The Unwanted: European Refugees in the Twentieth Century. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Moch, Leslie Page. Moving Europeans: Migration in Western Europe since 1650. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2003.

Sassen, Saskia. Guests and Aliens. New York: New Press, 1999.

Naimark, Norman. Fires of Hatred. Ethnic Cleansing in Twentieth-Century Europe. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001.

Ther, Philipp and Anna Siljak. Redrawing Nations. Ethnic Cleansing in East-Central Europe, 1944-1948. New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2001.

Toal, Gerald and Carl Dahlman. Bosnia Remade: Ethnic Cleansing and Its Reversal. New York Oxford University Press, 2011.

Wyman, Mark. DPs: Europe’s Displaced Persons, 1945-1951. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1998.