Every November we mark the anniversary of one of the most significant events of the 20th century—the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of communism throughout Eastern Europe. The opening of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989 triggered a wave of excitement and jubilation, as East Berliners were able to travel to West Berlin for the first time since the Wall was constructed in 1961. The world looked on in hope and amazement as the dominant symbol of the Cold War was dismantled with a remarkable lack of violence.

The Berlin Wall near the Brandenburg Gate, November 10, 1989

The events in Germany were part of a larger wave of anti-communist revolutions throughout Eastern Europe. The year 1989, often referred to as the annus mirabilis, also witnessed sweeping political transformations in Poland, Romania, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Bulgaria, as well as the protest movement in Tiananmen Square. Eventually, this process culminated in the disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1991.

For the lives of East Germans, the fall of the Berlin Wall ushered in a period of remarkable transformation. As depicted in the excellent film, Goodbye Lenin! (2003), hallmarks of Western capitalism such as Burger King and Coca-Cola quickly became ubiquitous in the formerly socialist landscape.

Yet, East Germany’s post-socialist transformation was neither simple nor painless. In addition to the changes wrought by privatization, the transition to a market economic system, and the influx of western goods, the 1990s also witnessed a struggle over how to remember the socialist era. Some advocated erasing all evidence of East Germany’s socialist past, while others recognized the utility of maintaining historical landmarks. In the end, Berlin’s urban planners created an impressive Berlin Wall Memorial that preserves the memory of Berlin’s tragic division (pictured left, the wall inscribed into the urban landscape).

In addition to questions of memorialization, reunified Germany also had to cope with lingering psychological and socioeconomic divisions between East and West Germans. And, there is an emerging generational gap between those who came of age after the collapse of communism and those who remember living in a world split between East and West. This generational gap is a common phenomenon evident in every post-socialist country of Eastern Europe.

In the West, the fall of the Berlin Wall became the symbolic marker of victory in the Cold War. For many, the demise of communism confirmed the superiority of free-market capitalism over the command economies of Eastern Europe. The Eastern Bloc’s rapid collapse even prompted political scientist Francis Fukuyama to declare the “end of history,” by which he meant the triumph of liberal democratic systems.

In the decades after 1989, Europe has witnessed an expansion of liberalism and the trend of European integration has continued. No longer behind the Iron Curtain, formerly socialist countries such as Poland, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria have become members of the European Union and NATO. Reunified Germany, led by the former East German resident Angela Merkel, has emerged as an economic powerhouse of this new Europe.

However, this process of European integration is neither straightforward nor irreversible. Some question the possibility of fostering a supranational “European” identity, and efforts to create an overarching European Constitution have faltered. Vestiges of authoritarianism, often with the guise of liberalism, remain in some of Europe’s post-socialist countries, notably Hungary and Russia. For many individuals throughout Eastern Europe, cynicism and political apathy have replaced the hope and optimism that characterized the annus mirabilis.

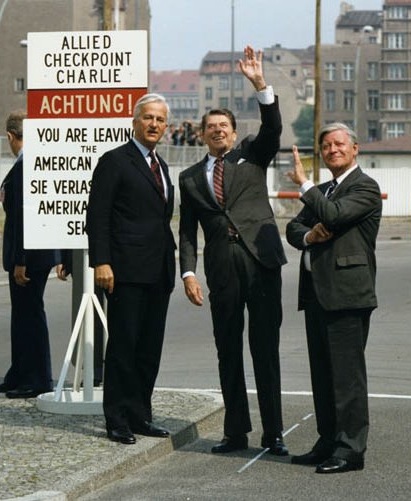

As evidenced by Ukraine’s recent Euromaidan revolution and Russia’s subsequent annexation of Crimea, the Cold War is not a distant history. Prominent public figures in both the United States and Russia commonly employ discourse that is highly reminiscent of Cold War rhetoric. Evoking John F. Kennedy’s famous “Ich bin ein Berliner” declaration in 1963, John McCain in 2014 insisted that “We are all Ukrainians.” Just as Berlin was the focal point of the East-West struggle of the Cold War, it appears that Ukraine may be the new center of European confrontation.

President John F. Kennedy in Berlin, 1963

We can see clearly now that the fall of the Berlin Wall did not usher in the “end of history,” but rather one more stage in Europe’s ongoing historical evolution. As we remember the 9th of November and marvel at the Berlin Wall’s immense symbolic potency, we should resist the temptation to oversimplify its meaning. Certainly, it stands for the demise of a bleak socialist world and the triumph of freedom and liberal democracy.

However, we should not limit our understanding of the Berlin Wall to the victory of a “good” West over an “evil” East, as these narratives tend to obscure the lived experiences of ordinary people and foreclose the possibility of further ideological evolution. An overly triumphant narrative risks hampering recognition of contemporary problems and conceals the shortcomings of the political, social, and economic structures that replaced the Soviet-era ones.

While the Wall—as the physical manifestation of a communist past—remains only as a museum, Eastern Europe’s post-socialist transition remains an ongoing process.

East German Guard talks to Westerner through Berlin Wall, November 1989 (left); West Germans peer at East German Guards, January 1990 (center); "Mauerspecht" [Wall Pecker] 1989 (right)

Read More:

Alexander Tolle, “Urban Identity Policies in Berlin: From Critical Reconstruction to Reconstructing the Wall,” Cities, 27 (2010): 348-357.

Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man (New York: Free Press, 1992).