In between memory and forgetting, there is commemoration. On June 4, 1989 a protest in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square ended in tragedy. As historical event, the contours of the Tiananmen student movement have long since entered textbooks in the West.

The story goes something like this: In the wake of Mao Zedong’s death (1976) and the end of the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), then-paramount leader Deng Xiaoping embarked on a series of economic reforms. Despite the success of this “second liberation,” inequalities and corruption—combined with an era of relative openness—led to calls for political change. In April of 1989, student commemorations of the late Party Secretary Hu Yaobang escalated into a wider protest, eventually numbering up to a million people, and gaining the support of Beijing citizens.

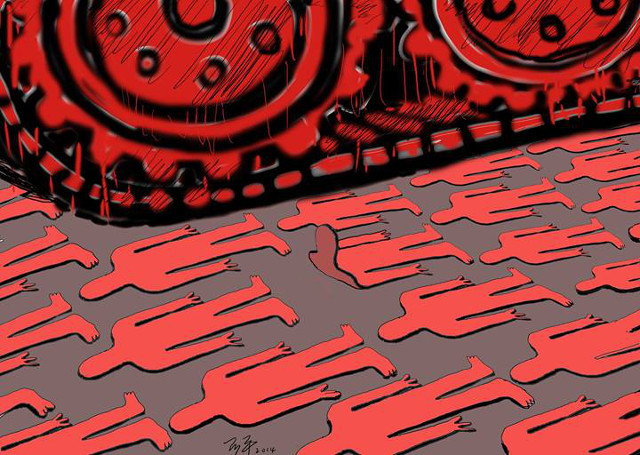

Participants on the square staged a dramatic hunger strike captured by foreign media and called for democracy. On the night of June 4th, the People’s Liberation Army moved into the heart of Beijing, armed with tanks and heavy artillery. The death toll remains disputed.

Today Tiananmen is referred to as an incident (shijian) by the Communist state, and as a massacre by its detractors. But there are other ways of referring to the event: the Chinese word for June 4th (liusi, or 6-4) is one, while May 35th—a way to allude both to Tiananmen and its enforced erasure from public discourse—is another. Both of these numbers are politically taboo, and are among the terms most rapidly scrubbed from the Internet.

Every year in the lead-up to the Tiananmen anniversary the Chinese state goes on high alert. Foreign journalists are warned not to cover the event, and Chinese intellectuals are arrested or otherwise made to disappear. Tiananmen Square, once carved from imperial grounds to create open political space for “the people,” once a place for kite-flying and for college students to study into the night, is cordoned off under the hot summer sky. It is perhaps a metaphor for the memory of June 4th itself, blank and guarded.

One cannot commemorate Tiananmen in China, and one word that threads through much of this year’s June 4th coverage is amnesia, wondering when, from forgetting, China will eventually wake.

In between patriotism and counterrevolution, there was the student. The Tiananmen movement began with a new generation of college student. In the 1980s, youths were once again allowed to go to college—after the Cultural Revolution’s disruptions—and through the 1980s they had been calling for greater freedoms.

These students followed in a long tradition of the intellectual-as-conscience in Chinese society. In imperial times, the upright official was to remonstrate his lord; in the eleventh century, the literatus Fan Zhongyan wrote that the intellectual was the first to worry over the world and the last to enjoy its pleasures.

In the twentieth century, when China became a republic, the new-style student inherited this mantle, becoming a voice for the nation. These college students, both men and women, would suffer in the post-1949 People’s Republic and possibly even pay with their lives. But even those who survived would remember that they studied to “save the nation” (jiuguo).

The students of 1989 consciously imitated their forebears. Recalling the nationalism of the May Fourth (1919) Movement, they called for “science and democracy.” In their hunger strike manifestos they invoked “Mother China” and bade farewell as patriots.

Yet to the state the students were counterrevolutionaries. Borrowing from the language of Maoist China, the official People’s Daily newspaper branded the movement as one incited by a “tiny handful of people [who took] this opportunity to fabricate rumors and openly attack Party and government leaders.” Indeed, the escalation of the student movement can be traced to the students’ own desire to proclaim that theirs was a “patriotic and democratic student movement.” To this day the judgment of the Party stands: PLA soldiers were martyred suppressing “counterrevolutionary rebellion.”

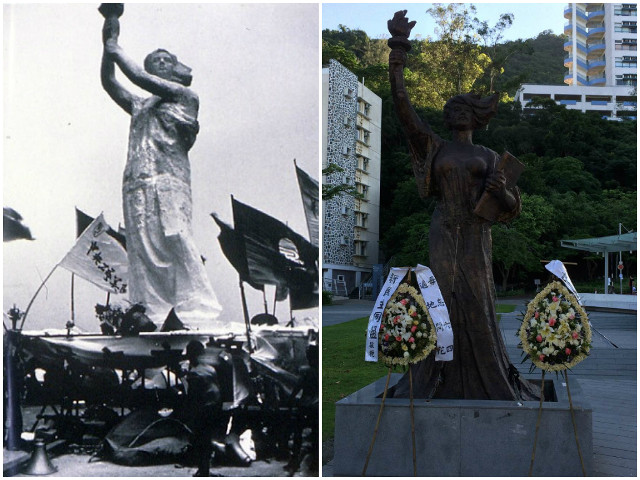

One way of remembering Tiananmen outside of China is to call the students the martyrs. In this year’s Tiananmen vigil in Hong Kong’s Victoria Park—where Tiananmen can be commemorated—the participants rally to rehabilitate (pingfan) June 4th. Almost 180,000 people attended the vigil, and in one of its most dramatic moments its organizers—the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China—marched towards the stage to a somber drumbeat and a reading of names, bearing a wreath for the fallen.

In between state and society, there is the individual. One of the most iconic images from 1989 is that of the “Tankman” (below right), a nameless Beijing citizen who was caught on camera in a face-off with one of the PLA’s tanks. A photograph that came to stand for the individual against autocracy, it has had a mixed legacy.

In the West, the image has alternately been used as a symbol for activists or, stripped of its original context, as a poster for the counterculture dorm room. In China, the photograph is not recognizable to young college students, and thus stands for Tiananmen amnesia.

We now know that the “Tankman,”  standing in the path of power with a plastic shopping bag, was someone called Wang Weilin, and his name was invoked by the most moving speaker at Hong Kong’s Tiananmen vigil. This individual was the rights lawyer Teng Biao, best known in the West for his defense of the blind human rights activist Chen Guangcheng. To six football fields of flickering lights, Teng argued that since Tiananmen 25 years ago, political suppression has continued, enumerating petitioners and prisoners, Tibetans and Uighurs, homeowners facing demolition, and lawyers and their own defenders.

standing in the path of power with a plastic shopping bag, was someone called Wang Weilin, and his name was invoked by the most moving speaker at Hong Kong’s Tiananmen vigil. This individual was the rights lawyer Teng Biao, best known in the West for his defense of the blind human rights activist Chen Guangcheng. To six football fields of flickering lights, Teng argued that since Tiananmen 25 years ago, political suppression has continued, enumerating petitioners and prisoners, Tibetans and Uighurs, homeowners facing demolition, and lawyers and their own defenders.

Teng’s speech, calling for another 1989 but not another June 4th, was inspiring less for his words and more for the drama of his presence. Of all the participants holding candles, he took the greatest risk in speaking out. Having known arrest, “disappearance,” and torture, he gave his voice to the crowd and to the commemoration, while his own family—unlike those of thousands of Chinese officials—is still resident in the People’s Republic.

In between China’s past and China’s present, there is the exile. If Teng Biao has come to live in a marginal space in China—instructed to vanish and forbidden to speak around Tiananmen’s commemoration— a generation of students who were nearly his contemporaries went into exile.

Most prominent among them was the Peking University history student and leader Wang Dan (pictured left), who earned a doctorate at Harvard and continues to be politically active outside of China. A video of several of the student leaders, including Wang Dan, was included in the Hong Kong vigil, offering their support of Tiananmen remembrance. Though the student-leaders have led checkered lives since exile, it is poignant to remember that none truly had the choice to reform the system from within. And poignant too is it to see their faces on the giant screens that flanked Victoria Park. In textbooks and documentaries, these men are fresh-faced, sporting long hair and blue jeans and looking not unlike our own students.

Most prominent among them was the Peking University history student and leader Wang Dan (pictured left), who earned a doctorate at Harvard and continues to be politically active outside of China. A video of several of the student leaders, including Wang Dan, was included in the Hong Kong vigil, offering their support of Tiananmen remembrance. Though the student-leaders have led checkered lives since exile, it is poignant to remember that none truly had the choice to reform the system from within. And poignant too is it to see their faces on the giant screens that flanked Victoria Park. In textbooks and documentaries, these men are fresh-faced, sporting long hair and blue jeans and looking not unlike our own students.

As the video flashes from historic photograph to contemporary video message, one is shocked by the faces of men middle-aged and heavyset. A young and intense Wu’erkaixi leads the 1989 crowd, perhaps to sing the Internationale. A man without a country, nearly fifty, broadcasts his greeting from Taiwan.

A second kind of exile is that of the Westerner’s reverse exile from China. In the days before this year’s June 4th anniversary, the American academic Perry Link came to speak at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, in a panel moderated by Teng Biao. Link was instrumental in the refuge in the American Embassy of astrophysicist and liberal intellectual Fang Lizhi. Thus, though Link devotes his life to the study and teaching of China, he can never return.

During the panel he joked that he had recently been invited to participate in a conference on Chinese literature, but when he asked organizers to check on the viability of his visa, the invitation was rescinded. Link continues to speak on behalf of the Chinese people; he published a book of Tiananmen documents, he testifies before Congress around Tiananmen anniversaries, and he translates petitions like the pro-democracy Charter ’08.

While Perry Link’s is one of the most prominent kinds of exile, the threat of self-inflicted banishment is one faced by journalists and other Sinologists every day. Though they are quick to point out that no risk is as great as that faced by their Chinese colleagues, it remains: studying China is dangerous.

In between the living and the dead, there is mourning. The commemoration in Hong Kong’s Victoria Park was meant to be a vigil for martyrs. Many of the attendees were dressed in black, they lit candles from one to another, and as the organizers lay a traditional wreath before a makeshift monument they led the audience in the ritual bowing initiated in Republican times: “First bow. Bow again. The third bow.”

China’s Communist state is finely tuned to the political significance of public mourning. Mourning can be orchestrated by the state, as it was for the funeral of Sun Yat-sen or for the death of Mao in 1976. But public mourning remains a flashpoint for political sentiment, as it was for the death of Zhou Enlai or the mourning of Hu Yaobang that sparked Tiananmen, and for the children who died when shoddy school buildings collapsed during the recent Sichuan earthquake.

Once the master of its own political spectacle, the Communist Party can no longer afford to allow Tiananmen Square to be open for mourning (literally and metaphorically). One must be searched to enter the Square.

And neither are people allowed to mourn in private. An activist group known as the Tiananmen Mothers has long sought redress in the deaths of their children, but especially in the lead-up to this anniversary their members have been put under surveillance and forbidden to travel. Hong Kong’s South China Morning Post reported that only a few family members were allowed to visit the graves, and Zhang Xianling of the Tiananmen Mothers reports being watched by twenty policemen. Unable to invite any of the Tiananmen Mothers to attend the Hong Kong vigil, organizers instead showed grainy footage of previously recorded videos.

The Communist Party’s unease with mourning reflects the tenuous state of history in China. Deaths from the Great Leap Forward famine are taboo, the one officially recognized Cultural Revolution cemetery in Chongqing is chained and locked, and gravesites are carefully watched. One recalls from the Maoist era that a counterrevolutionary could not be mourned by his own parents, even as Mao-era propaganda critiqued the pre-1949 “old society” for rending the home asunder and even as the family was required to pay for the executioner’s bullet.

In between China and the world, there is Hong Kong. Many of those who commemorated Tiananmen in Hong Kong this month see the former British colony as the last redoubt, the canary in the coal mine. The Hong Kong Alliance, the vigil’s organizer, was founded before the handover and it is doubtful whether such a group could be established today. Teng Biao, the rights lawyer speaking from the Victoria Park stage, thanked Hong Kongers for “keeping the memory of the Tiananmen movement alive,” and underlined that “Hong Kong has no place to back down either.”

To be clear, Hong Kong’s relationship with the mainland is deeply fraught. Many are frustrated with the lack of universal suffrage and constricted press freedom, and tensions rise with the perception that mainland Chinese are taking jobs and other resources. Observers have argued that this year’s Tiananmen vigil was a proxy for protesting against China. The cynical view is that Hong Kong feels Chinese on two occasions: during the Olympics, and when commemorating June 4th.

After the immediate post-June 4th-whirlwind of media coverage, life in Hong Kong seems to have returned to normal. At Chinese University, where a permanent statue pays tribute to the Goddess of Democracy erected by Beijing students in 1989, the wreaths laid by the students’ association had vanished. In the high-end shopping districts, one’s Chinese compatriots (tongbao) are back to queuing up to get into Louis Vuitton.

But Hong Kong remains the place where journalists can write and where academics can publish, where an activist like Teng Biao can defy his marching orders and tell 180,000 people to carry the torch. Nonetheless, his refuge is a temporary one. Not everyone was allowed into Hong Kong to commemorate June 4th, and no one yet knows what will await Teng when he returns. Between the voice and the mouthpiece, between the pen and the sword, there is courage.