We are living in a new Viking Age. They are everywhere in media culture—from TV shows and literature to museum exhibits. But what do we really know about the Vikings? This month author Genevieve Gornichec examines the history of the Vikings and the way they have been mythologized to disentangle popular images from historical reality.

There’s no denying that the Vikings and Norse mythology are having a moment.

From History Channel’s Vikings to Marvel’s Thor films, to Robert Eggers’ The Northman, to shows like Netflix’s Ragnarok and Norsemen, to screen adaptations of Neil Gaiman’s American Gods and Bernard Cornwell’s The Last Kingdom novels, to other novels like Rick Riordan’s Magnus Chase and the Gods of Asgard and Joanne Harris’s The Gospel of Loki, to video games like Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla, and God of War: Ragnarok—the list simply goes on and on.

This is certainly not the first time these fearsome raiders and their gods have enjoyed the spotlight, despite their uptick in popularity over the past decade or so. They’ve been capturing our imagination for centuries.

Today, we tend to categorize the so-called Viking Age as lasting from approximately 700 CE to 1100 CE. More specific years are often used, but just because the Vikings entered the written historical record at the sacking of Lindisfarne monastery in 793 CE doesn’t mean they didn’t exist beforehand.

Likewise, although Norwegian king Harald Hardrada lost the battle of Stamford Bridge in 1066 CE, this doesn’t mean Vikings everywhere simply vanished. There were many “ends” to the Viking Age, but one most often cited is the correlation between the spread of Christianity across Scandinavia and the declension of the Viking raids.

But who really were these famous figures? What happened between then and now? Why do the stories and imagery of the Vikings still have such a firm hold on our collective consciousness a millennium later? And does it matter how they are portrayed in modern media?

What We Know

The origin of the word “Viking” has been hotly debated, but most scholars agree that it refers to a job title or an activity—the act of going raiding—rather than a race of people.

A very small portion of Scandinavians at the time were Vikings; most, in fact, were farmers. They were also pagans, though much of what their worship and ritual truly entailed is lost to us, and the surviving descriptions of such things are questionable.

Homeland Viking-Age Scandinavians also had a detailed legal system and honor code that expected certain behaviors from free men and women. They convened at regional assemblies called “things” where free men would gather to voice grievances and settle disputes, especially those regarding theft or slayings.

Kinship ties were also immensely important, for one often needed community support at the assembly to win a legal case. Thus, in contrast with the Vikings’ misbehavior abroad, the surviving law codes indicate that, at home, they were bound by strict legal and societal expectations that, when broken, could have dire consequences, from fines to generations-long blood feuds.

And despite women having little direct political authority under the law, we also know that in the North Atlantic, the production of textiles gave free women considerable power in their society, and, according to the sagas, many women were proactive when it came to deciding their own fates.

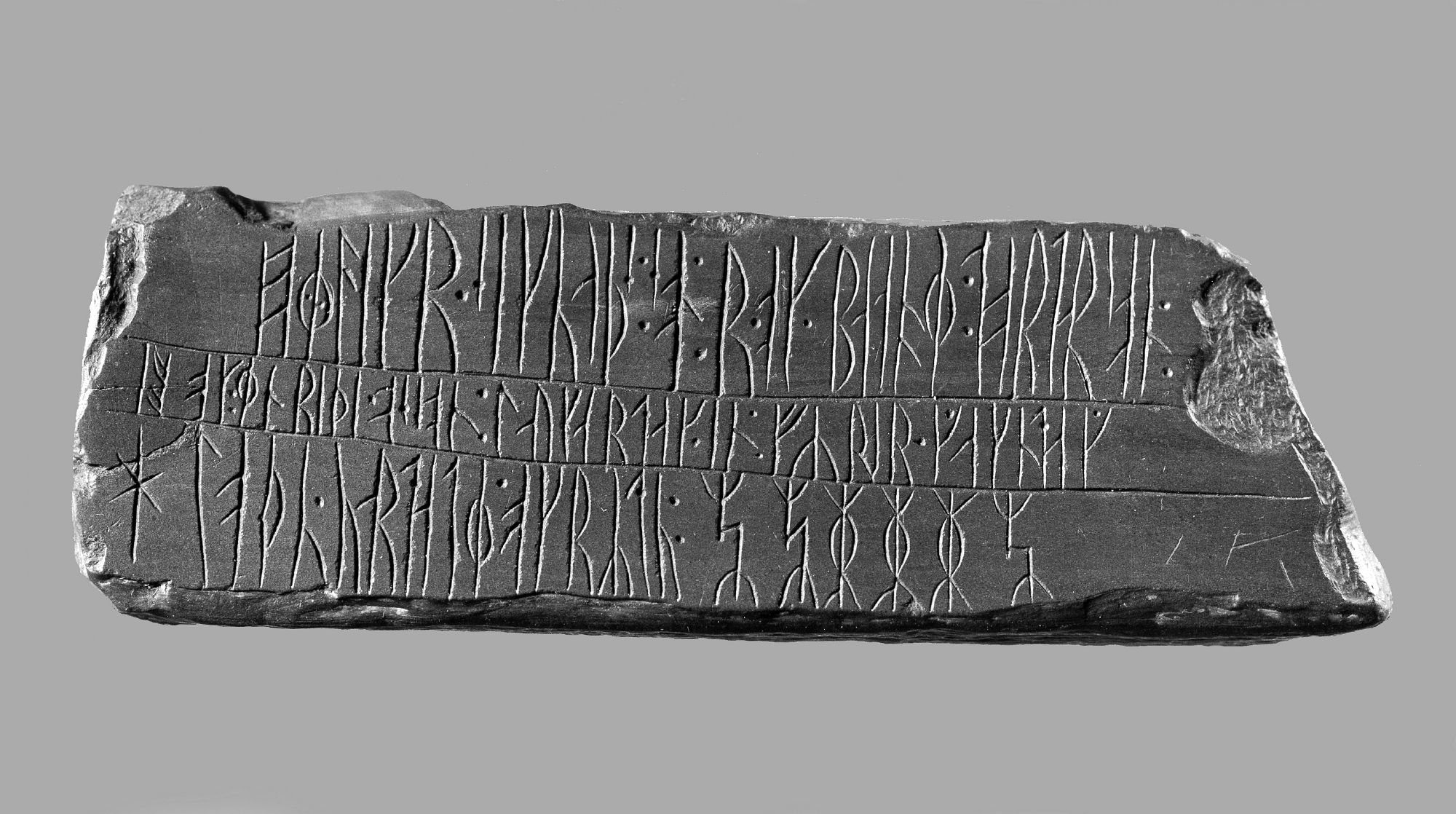

However, how we know what we know about the Vikings requires further examination. Viking Age Scandinavia was an oral society, and writing was limited to runic inscriptions and carvings on bark or stone. This means that contemporary accounts of the Viking Age largely come from the people being raided.

There are many later accounts of Viking exploits and Nordic mythology from within Scandinavia and Iceland, but they were written by the Christian descendants of the people who lived these stories and revered these gods hundreds of years later. Even their law codes come to us from a later time, though they were thought to have been employed during the Viking Age as well.

The Emergence of Viking Age Stories

Nevertheless, the existence of these tales alone suggests they were relevant enough to remember. Icelanders in particular had a keen interest in history, as evidenced by works such as The Sagas of Icelanders, a corpus of stories set in the Viking Age, along with Snorri Sturluson’s Prose Edda and the poems compiled in the Poetic Edda. These two thirteenth-century works are where most of our knowledge of Norse mythology comes from.

Many of the myths and sagas are thought to have been passed on orally for generations before the Icelanders began to pen their histories around 1100 CE, but the extent to which they are accurate depictions of life and worship in the Viking Age will never truly be known.

It wasn’t until the seventeenth century that these stories began making their way out of Iceland. Translated into Latin, the myths and sagas soon became of major interest to the rest of Europe and beyond. In England and what would later become Germany, there was an increasing interest in an idealized version of the “Old North” depicted in the sagas.

In the nineteenth century, Englishman William Morris, collaborating with Icelander Eiríkr Magnússon, translated more than thirty sagas into English. Though Morris was not the first one to do so, his work found a captive audience: the Victorians loved Vikings.

In previous centuries, the English had considered the Vikings to be barbaric and unrefined, but over time this image was overwritten, transformed into that of a noble ancestor that embodied freedom and self-reliance. It’s easy to see why the Sagas of Icelanders in particular appealed to Gothic sensibilities, with their tales of tragic heroes, violence, vengeance, and doomed love amid bleak, windswept landscapes.

The English weren’t alone in romanticizing the Viking Age. The nineteenth century was a period in which many countries in Europe were looking backward to form their national identities.

While the English saw the Nordics as sort of a distant cousin due to the Vikings’ influence on the isles, the Germans saw the Nordics as sharing a common cultural heritage, not only through some of their folklore but by a linguistic common ancestor, Proto-Germanic, from which Old Norse, Old English, and Old German evolved. This developed into an argument that, if one went far enough back in time, English, Germans, and Scandinavians were at one time a single Germanic people.

In a newly unified Germany, this idea took root and held fast. This was aided in no small part by the cultural phenomenon that was Richard Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of the Nibelungs), an operatic cycle composed in the latter half of the nineteenth century. The operas were based largely on Der Nibelungenlied (The Song of the Nibelungs), an epic poem written in Middle High German circa 1200.

Der Nibelungenlied shares undeniable parallels with the legendary Old Norse Volsunga saga (The Saga of the Volsungs), indicating that these tales stemmed from a common source that had been known in the Germanic-speaking world for centuries prior to their being finally written down in the Middle Ages. Volsunga saga features such memorable characters of the dragonslayer Sigurðr and the Valkyrie Brynhildr; in Wagner’s opera, these two became Siegfried and Brünnhilde.

The Old Norse myths and sagas in particular were of special interest to North Americans as well, who were also not exempt from the uptick in interest in the “Old North” in the nineteenth century.

Two medieval Icelandic sagas, The Saga of Eirik the Red and The Saga of the Greenlanders, collectively known as the Vinland Sagas, made the claim that the first European to arrive in the Americas was not Christopher Columbus but Leifr Eiríksson (commonly Anglicized as Leif Ericson), who sailed from Greenland to the east coast of Canada around the year 1000.

Although evidence of a Norse presence in North America was not discovered until the 1960s at L’anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland, white Americans in the Victorian era joined the British and Germans in rehabilitating their previous image of the Vikings from violent, bloodthirsty marauders to independent, freedom-loving, civilized people—just like themselves.

A great deal of our public perception of the Viking Age today can be traced back to the Victorian era. Wagner’s work in particular has been significant in later cultural images of the Vikings; for example, he was the one who popularized the idea of the Vikings wearing horned helmets, an iconic symbol that continues to pervade modern imagery of the Vikings despite having long since been disproven.

The idea, too, that Vikings drank from the skulls of their enemies was due to an earlier mistranslation, but Victorians accepted it because it fit with the image of the Vikings they had already created.

The trend of reimagining the Vikings as the pinnacle of Western civilization set the stage for an even darker turn of events when the Nazis began appropriating Old Norse text and imagery to further their ideologies in the early twentieth century.

Adolf Hitler himself was a big fan of Wagner’s operas. To him, the Nordics exemplified his idea of a “master race”—not least because Scandinavia had converted to Christianity much later than the rest of Europe and had therefore managed to preserve more of the “old ways”—whose shared heritage Germans could also claim.

Hitler and several higher-ups in the Nazi party even tried to revive Old Norse paganism (as “Wotanism,” or modern-day Odinism, an inherently racist sect of the Norse pagan revival). The result of this was that, for a long time afterward, the Viking Age and Norse myths were unfortunately (and to some degree, still are) heavily associated with white supremacy.

Vikings on Screen and in Song

In the decades following World War II, the more immediate association of the Old Norse myths and sagas with Nazism began to fade, prompting another resurgence of interest in the Viking Age.

Films like The Vikings (1958) starring Kirk Douglas is an example of how postwar creators attempted to distance themselves from the Victorian image of the Vikings as an honorable, civilized forebear, instead hearkening back to the violence and aggression that characterized how Europeans saw the raiders prior to the Enlightenment.

Films such as Terry Jones’s Eric the Viking (1989), along with The 13th Warrior (1999), continued this trend of reexamining, corroborating, and challenging previous perceptions of the Vikings.

To use one example, The 13th Warrior was based on the novel originally titled Eaters of the Dead by Michael Crichton, itself loosely based on the accounts of Muslim travel writer Ahmad ibn Fadlān, which details his encounters with Vikings on the Volga River in the early tenth century.

In the film, the character of ibn Fadlān, played by Antonio Banderas, is unwillingly thrust into a quest with a dozen Vikings. While at first his relationship with his new companions seems incompatible due to extreme linguistic and cultural differences, throughout the course of their journey, he and the Vikings learn from each other and are fundamentally changed by the time they part ways.

This narrative reflects the historical reality of Scandinavians in the Viking Age: although they were known for their violence and Otherness to those writing about them at the time, many Vikings who traveled abroad tended to assimilate into the cultures where they settled or bring bits of that culture home—evidenced not just by literary works but archaeological sources such as the ring found in a ninth century woman’s grave at Birka, Sweden, inscribed with “to/for Allah.”

When it comes to Norse mythology, one of the most widely recognizable cultural touchstones to appear following World War II was undoubtedly Marvel’s The Mighty Thor. Created in the 1960s by Stan Lee, Jack Kirby, and Larry Lieber, the bright, campy Thor comics reimagine the god as an alien hero banished to Midgard (Earth) with no memories in order to learn humility.

The rest of the pantheon make appearances as well, most notably a particularly villainous Loki, who in this version of events is Thor’s adopted brother instead of Odin’s blood brother as he is in the original myths. Thor also eventually becomes part of Marvel’s superhero team, the Avengers.

More recently, the big-screen adaptations of the Thor comics as part of the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) have also resulted in a renewed interest in Norse mythology, both in terms of fandom and spirituality.

While the first Thor film premiered in May 2011 to considerable fanfare, the figure of Loki in particular experienced an explosion in popularity as the main villain of both Thor and The Avengers (2012), a film which grossed over $1.5 billion worldwide.

While there’s little evidence that this famously complicated trickster figure was worshipped during the Viking Age (at least to the same degree as, say, Thor, Odin, and Freyr), it’s clear that modern audiences have found something in Loki to connect with, both as a character and as a deity.

The year after The Avengers debuted came another cultural phenomenon: History Channel’s Vikings. It’s impossible to overstate the effect this television show has had on the public perception of the Viking Age.

The story begins in 793 CE with the main character—the quasi-historical Viking Ragnar Lothbrok—“discovering” England and sacking Lindisfarne monastery and follows him through the rest of his life, then moves on to follow his sons.

The brutality and hardship of this time period is not glossed over and includes depictions of not just bloody battles and the infamous (and questionably historical) “blood eagle”, but also sexual violence and slavery, alongside broader themes of religion, romance, and loyalty.

Although the show conflates and rearranges certain significant historical events and its portrayal of certain cultures leaves much to be desired, it’s important to consider that Vikings is primarily meant as entertainment, not as a documentary.

History, as it is passed down to us, does not always make a good story—at least not to modern Western consumers, who expect narratives to have a beginning, a middle, and a definitive, satisfying end. But the story the showrunners crafted was clearly compelling enough to make Vikings into the wildly successful show it became.

The writers were able to make audiences become invested in the lives of people who lived over a millennium ago, whose world and mindset is completely alien to us in the 21st century.

In a world where no one batted an eye at enslaved people and even the “good guys” could be violent and cruel, how are we supposed to overlook these things enough to feel that we have anything to relate to? Vikings manages to establish that connection.

One might even argue that the success of Vikings paved the way for many of the shows and books mentioned in the first paragraph of this article, with some leaning more toward authenticity than others.

In particular, The Northman (2022), a film by Robert Eggers, borrows heavily from the Sagas of Icelanders in terms of tropes and character archetypes. Eggers also employed historians as advisers, alongside artisans who specialize in reproducing artifacts for Viking Age living history. Filmed largely in Ireland and Iceland, the film is truly a feast for the eyes, especially for those who know what to look for.

Music is another area that is hotly debated among those interested in the Viking Age, as no written music and very few instruments survive from this time.

In keeping with the strong link between magic, music, and poetry that we see in the Old Norse literary sources, many modern Norse pagans feel a strong spiritual connection to music, specifically that of bands like Wardruna and Heilung, who heralded the rise of a genre that has since been dubbed “dark Nordic folk.”

Using reconstructed historical instruments to perform songs in ancient languages like Proto-Germanic and Old Norse, chanting, throat-singing, and incorporating elements of nature like rushing water and animal sounds into their tracks, these bands, and the many others that have followed them, seek to resonate with something deep and timeless within the listener.

Though this genre has a significant appeal to those interested in Viking Age history and spirituality, Einar Selvik, the frontman of Wardruna, does not use the world “Viking” to describe what he does; rather, he says, his music is about “taking something old and making something new with it,” giving the distant past meaning to us in the modern day.

As far as modern interpretations of the Vikings are concerned, while misinformation and misrepresentation are perennial issues—not to mention the appropriation of the past to further hateful agendas—one cannot discount the influence of pop culture when it comes to garnering interest in history.

And even though historical advisors can consult on creative projects, the final decisions often reside with the creators, and it’s up to them to be diligent, responsible, and transparent in their portrayal of the stories and figures they are working with. In the same vein, it’s up to the audience to do their own research as well. Fiction does not exist in a vacuum; neither does the past.

Making Use of the Viking Past

When most people think of the word “history,” they think of long lists of names and dates and battles. But presenting it in a way that speaks to an audience on an emotional level—be it film, music, television, video games, or books—makes the past a real, tangible, relatable thing that has a life of its own. And connecting with history can contribute to an individual’s sense of self in the world today.

This was the case long before these mediums became more widespread in the twentieth century. “How often does historical enquiry have less to do with establishing past facts, and more to do with the establishing of present identity?” asks historian Eleanor Rosamund Barraclough in a recent article. The answer, as has hopefully been demonstrated throughout the course of this article, is resoundingly: often, if not always.

Taking all this into account, it seems the Vikings have enjoyed continued popularity due not only to their widespread influence during their own time period, but also their malleability after the fact.

That there are so many unknowns, both in the literary and archaeological sources, opens the door for all sorts of interpretations, for better or worse. The Vikings have kept both academics and armchair historians debating who they “really” were for hundreds of years and will likely continue to do so for a long time to come.

For people who did not write down their own stories, it’s clear that the Vikings are still speaking to us, even if it’s difficult—often impossible—to separate their voices from our own.

In a recent interview on the Nordic Mythology Podcast, Marianne Moen, an archaeologist at the Museum of Cultural History at the University of Oslo, states, “I don’t believe in a past—I think we always create the past in the present, and that the stories we tell of the past are the stories that we choose, because they flatter our present or they tell us who we want to be. I just don’t believe there is a Viking Age that isn’t created by us in the here and now, and it reflects us more than it reflects the Vikings.”

One thing is certain: one of the reasons we keep revisiting and reimagining the Viking Age is because we are searching for our own meaning within it, something to resonate with us in our current time and place, something to connect to. And although we have carried them with us through the centuries, where we will take the Vikings next still remains to be seen.

Barraclough, Eleanor Rosamund. “The Great Viking Fake-Off: The Cultural Legacy of Norse Voyages to North America.” In The Vikings Reimagined: Reception, Recovery, Engagement, edited by Tom Birkett and Roderick Dale. Boston, Berlin: De Gruyter/Medieval Institute Publications, 2019.

Bernstein, Mary. “That’s MY Deity: An Examination of Online Lokean Cultures through Log-Linear Modeling.” Senior Theses, 2023. https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/senior_theses/594

Driscoll, M.J. “Vikings!” In The Vikings Reimagined: Reception, Recovery, Engagement, edited by Tom Birkett and Roderick Dale. Boston, Berlin: De Gruyter/Medieval Institute Publications, 2019.

Fitzgerald, Padraic and Nordvig, Mathias. “Spellbinding Skalds: Music as Ritual in Nordic Neopaganism.” In Living Folk Religions, edited by Sravana Borkataky-Varma and Aaron Michael Ullrey. London: Routledge, 2023.

Kramer, Miles. “Forever Conquered: The Changing Role of Vikings in Modern and Contemporary Anglo-American Culture.” Iowa Historical Review vol. 10 issue 1, 2022. https://doi.org/10.17077/2373-1842.31872

Larrington, Carolyne. Norse Myths that Shape the Way We Think. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd, 2023.

Price, Neil. “My Vikings and Real Vikings: Drama, Documentary, and Historical Consultancy.” In The Vikings Reimagined: Reception, Recovery, Engagement, edited by Tom Birkett and Roderick Dale. Boston, Berlin: De Gruyter/Medieval Institute Publications, 2019.

Russo, Francine. “Viking Textiles Show Women Had Tremendous Power.” Scientific American, October 1st, 2022. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/viking-textiles-show-women-had-tremendous-power/