Most of us would have a hard time locating Transnistria on a map. But as historian William Zadeskey writes, this tiny piece of land located between Ukraine and Moldova may prove a critical piece of the struggle between Russia and the rest of Europe. This month we offer an introduction to the recent history of this multi-ethnic region.

Nestled between the Dniester River to the west and the Ukrainian border to the east lies the self-proclaimed breakaway state of Transnistria. The Pridnestrovian Moldovan Republic (PMR)—to use the official name—is internationally recognized as a part of Moldova but has maintained de facto independence since 1992.

Transnistrians were once the masters of their own destiny. But now Russia exploits this region and its people to further Moscow’s geopolitical goals in its imperishable conflict with the West. A recent series of bombings has threatened a 30-year peace in this oft-forgotten corner of Europe.

Since April 25, 2022, eight attacks have occurred across the left bank of the Dniester, raising concerns that the Russian war in Ukraine could spill over into Transnistria and Moldova. Transnistrian authorities have released little about who is responsible for the attacks. So far there have been no casualties and damage has been relatively minor. These attacks range from crude Molotov cocktails thrown at government buildings to more sophisticated attacks by grenade-armed drones.

The most destructive bombing occurred near the village of Maiak on the morning of April 26, when five to ten individuals planted 12 anti-tank mines at a telecommunications complex, destroying two large radio antennas. More recently, a drone dropped two grenades on a parking lot used by Russian peacekeeping troops on June 5.

While the culprits of what the Transnistrian government has called “terrorist acts” remain unknown, the Moldovans, Ukrainians, and Transnistrians— along with their Russian allies —have all labeled the bombings as provocations meant to destabilize the region.

Regardless of who is culpable, Transnistria has been caught up in Russia’s geopolitical game with Ukraine and the West. Today, Transnistria exists as a Russian pawn and a vessel for Russian nationalism and neo-imperialism. Yet since the 1990s, the multi-ethnic Transnistrian population has asserted its commitment to linguistic equality and multiculturalism. Exploring the self-proclaimed state’s history illustrates the region’s post-Soviet shift from multiculturalism to Russian domination.

A Multi-Ethnic Borderland

As the frontier between eastern Latinity and Slavdom, this 127-mile strip of land has long been a multi-ethnic borderland populated by Moldovans, Russians, and Ukrainians. Over the past 2,000 years, the land that is today the PMR changed hands among various Eurasian nomads, Kyivan Rus, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and the Ottoman Empire.

By the late 1700s, the territory had been absorbed into the Russian Empire by the famed General Alexander Suvorov. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, a rural, Romanian-speaking population began to migrate to the left bank of the Dniester, which had mostly been ethnically Ukrainian, from Bessarabia (the historic name for the modern Republic of Moldova).

During Soviet rule, Transnistria—its population still largely Ukrainian—was united with Bessarabia to form the Moldovan Soviet Socialist Republic (MSSR) in 1940. Yet crucial demographic and social changes in Bessarabia and Transnistria drove a wedge between the two regions.

Historically, the people of Moldova were considered to be of Romanian origin and spoke a dialect of standard Romanian. A century of Russian rule, however, caused the Romanian speakers of Bessarabia to miss the important events of Romanian nation building experienced by their neighbors on the western side of the Prut River, which sits today as the border between Romania and Moldova. Thus, Bessarabians lacked a strong affiliation with the Romanian nation-state.

Beginning in the 1920s, the Soviet state fostered the development of a unique Moldovan nation through the creation of a Moldovan language in the Cyrillic script and a singular proletarian Moldovan identity. By the late 1980s, these efforts, combined with the elevation of nationalistic native Moldovan elites, had engendered Moldovan nationalism. State-sponsored nation building caused Bessarabia to become more ethnically Moldovan as well.

Conversely, Transnistria became more ethnically diverse, the result of an influx of tens of thousands of Russian-speaking immigrants who came to labor in the left bank’s vast heavy industry. This ethnic migration resulted in its current ethnic diversity: 158,000 Russians (33.8%), 153,500 Moldovans (33.2%), and 124,200 Ukrainians (26.7%).

Throughout the Soviet period, these ethnic populations lived in harmony, freely speaking their respective languages and intermarrying. Thus, nationalism was traditionally an unappealing ideology to the multi-ethnic communities of Transnistria.

The Rise of Moldovan Nationalism and the Transnistrian Response

Tensions between the two regions of the MSSR emerged as early as 1988 as a portion of the population in Bessarabia started to advocate for nationalist policies and eventual independence from the Soviet Union.

The Popular Front of Moldova (Frontul Popular din Moldova, FPM) spearheaded the cause of Moldovan nationalism beginning in May 1989. They had three main grievances: the of use the Cyrillic alphabet for the Moldovan language, the sidelining of Romanian in favor of Russian, and the undefined relationship between the Romanian and Moldovan languages.

These concerns were well founded. Moldovans lamented that Cyrillic was incompatible with their native language. One man explained that the last names of all six of his children were spelled differently because of inconsistencies in Moldovan Cyrillic. The Moldovan nationalists pushed to have Romanian in the Latin script—as opposed to Moldovan in the Cyrillic script—be recognized as the state language. Three laws promoting this change were adopted on August 31, 1989.

Further, Moldovans felt that their language was marginalized, arguing that most media was available only in Russian. Finally, the question of the historic unity of Moldovans and Romanians prompted the nationalist forces to demand the state recognize these two groups as a single ethno-linguistic unit. Similar pushes for nationalism occurred across the USSR in the late 1980s, making the events in Moldova part of a larger late-Soviet trend.

The Popular Front of Moldova, once the largest nationalist and pro-democracy organization in the republic, began to advocate pan-Romanianism in late 1989 and especially in 1990. Pan-Romanian rhetoric, the adoption of the Romanian tricolor flag on April 26, 1990, and widespread talk about a union with Romania sparked fears of so-called “Romanianization” among the multicultural population of Transnistria.

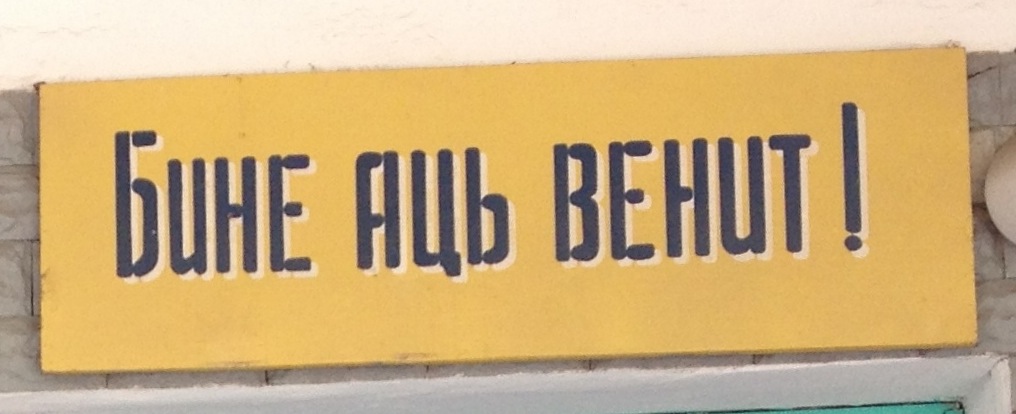

Prior to the passage of laws promoting Romanian as the state language, Transnistrians organized politically in the form of the Joint Council of Labor Collectives (Ob”edinennyi soviet trudovykh kollektivov, OSTK). From its inception, the OSTK was a political organization centered on stopping the pro-Romanian language laws.

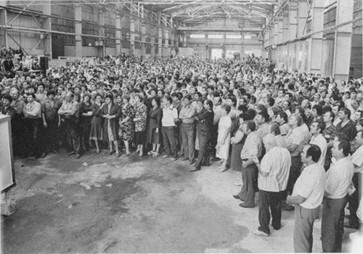

Founded on August 11, 1989, the OSTK politically united all of Transnistria for the first time in its history. These labor collectives were based in the numerous factories and plants across the left bank. Widespread, OSTK-organized strikes drew thousands of participants.

To the OSTK, the perceived imposition of Romanian language represented excessive Romanian influence and a threat to their cherished linguistic equality and multiculturalism. Thus, in the vein of Soviet nationality policy, they advocated for official equality between Moldavan and Russian. Russians as well as Ukrainians and other minorities relied on Russian as the language of inter-ethnic communication.

Although the OSTK was largely populated by Slavs, ethnic Moldovans in Transnistria supported its mission of granting both Moldovan and Russian official status. The support of ethnic Moldovans in Transnistria illustrates that at the very beginning of the Moldovan-Transnistrian dispute in 1989 and 1990, the OSTK advocated for linguistic equality and multiculturalism rather than pure Russian nationalism.

These Moldovans lived as members of multicultural communities and families, causing them to oppose the promotion of Romanian above Russian on the grounds that it would disadvantage the non-Moldovans around them.

Take for instance the statement of Anatolii Kharlampievich Tabak, as reported by Sovetskaia Moldavia in early August 1989: “I am a Moldovan, my wife is Russian, my kids study in Ukraine. I have understood Russian my whole life. I believe that Russian and Moldovan should have the same rights.” Multinational families like Tabak’s were very common in late Soviet Transnistria.

Another Moldovan explained that he favored equal rights over nationalism because, “it can’t be good for me if it hurts someone.” These Moldovans chose to eschew nationalism because doing so would mean turning their backs on their non-Moldovan family members and neighbors.

These multinational families and individuals simply could not be placed into the nation-state model that Moldovan nationalists in the capital Chișinău hoped to foster. Transnistrian support for both Russian and Moldovan language use in the early 1990s was not a way to push Russian chauvinism but was done to promote ethno-linguistic equality in the region.

Toward War and Separation

When the OSTK strikes had no effect on Chișinău’s nationalist and pan-Romanian policies, Transnistrians sought political separation from the rest of Moldova.

Since the 1920s, the Soviet Union had used regional autonomy to foster and protect linguistic and cultural autonomy. The Transnistrian push for autonomy, then, was a continuation of this old Soviet idea.

After a series of referendums, the multicultural populace unilaterally established the Pridnestrovian Moldovan Soviet Socialist Republic within the USSR on September 2, 1990. Once it had become clear that the Soviet Union was careening toward collapse after the failed August coup against Mikhail Gorbachev, the government in Tiraspol declared the creation of the modern PMR on August 25, 1991.

By March 1992, the political dispute between Tiraspol and Chișinău escalated into open warfare. In June the Russian 14th Army, which had been stationed in Transnistria since the 1950s, intervened on the Transistrian side.

Why the Russian army—commanded by the bold, headstrong General Alexander Ivanovich Lebed—joined the conflict is unclear. At the time, the Russian defense minister revealed that Lebed was not acting on orders from Moscow. In all likelihood, the Russian soldiers themselves decided to intervene because they had become deeply ingrained in Transnistrian society, marrying locals and considering the region their home.

With this support, the Transnistrians fought to a stalemate with the Moldovans. A ceasefire in July 1992 secured Transnistria’s de facto independence, and created the peaceful, yet unending, “frozen conflict” between Tiraspol and Chișinău. In the three decades since, Russia has worked to keep the conflict going while Russian chauvinism and nationalism have come to dominate Transnistria.

The Rise of Russian Nationalism

As the conflict wore on, the multicultural Transnistrian agenda was usurped by a wave of Russian nationalism. During the war, some Transnistrians feared losing their Russian identity to “Romanianization.” This was not a new concept to the Slavs on the Dniester.

Since the late 1880s, Russian-language publications had detailed stories of Slavs “succumbing” to Romanian influence, all designed to shock the reader. According to these accounts, individuals lost not only their knowledge of the Russian or Ukrainian language, but their identity as a Slav and Slavic way of life as well. The 1992 war and Moldovan nationalist policies resurrected these old fears among Transnistria’s Slavs.

Further, Transnistria’s attempt at linguistic equality has instead resulted in Russian becoming the de facto state language. The PMR’s constitution clearly established that Moldovan, Russian, and Ukrainian all held equal status within the self-declared state, yet Russian has taken a dominant position. The largest newspaper in Romania even claimed that use of Moldovan and Ukrainian was discouraged in Transnistria, calling the situation “Russification.”

As far back as April 1989, Moldovan nationalists argued that Russian could not be granted status as a state language of Moldova, because—as the lingua franca—it would usurp Moldovan and become the de facto state language; Transnistria has proven this concern prophetic.

Statistics on the language of education from the 2019 census provide a light into Russian’s elevated status in the PMR. Despite Russians making up just 33.8% of the Transnistrian population, 93% of preschoolers were taught in Russian. Of the region’s 150 schools, 112 of them taught solely in Russian. Further, slightly more than 10% of pupils were educated in the Moldovan language and only 400 students received education in Ukrainian. At higher levels of education, Russian’s dominance is even more pronounced.

Yet despite these figures, Moldovans in Transnistria appear content with Russian’s dominance in the region. The Transnistrian government has taken an active role in preserving the Moldovan language by funding textbooks, literature, and Moldovan language newspapers and television programs. For these efforts, the Union of Moldovans lauded the state for protecting the unique Moldovan script and language.

The acceptance of the predominance of Russian by the ethnic Moldovans is not surprising given than in the 1990s these left bank inhabitants advocated for the official status of Russian in addition to the freedom to utilize their own language. Moreover, these Moldovans were not and are still not concerned with Russian holding a de facto place of privilege.

On the other hand, those ethnic Moldovans who felt threatened by the excessive prominence of the Russian language likely have been among the 70,000 Moldovans who have left Transnistria since 2001.

Russia’s Heavy Hand

Russian nationalism has recently emerged in Transnistrian politics and society, the most prominent example of which is the Transnistrian government’s goal to join the Russian Federation.

The Transnistrian president, Vadim Krasnoselsky, has called joining Russia Transnistria’s “fate.” Romanian media reported that Transnistrian officials traveled to Moscow in February 2022 in hopes of being recognized as an independent state like the self-proclaimed Donetsk and Luhansk republics in Ukraine had been.

In March, Belarusian president Alexander Lukashenka carelessly revealed Russian battle plans to send troops into Transnistria. The Belarusian ambassador to Moldova tried to walk back the battle plans, claiming they were a mistake.

Like Putin, Transnistria has revived the grand Soviet-esque Victory Day parades in an effort to highlight the state’s historic ties to Russia. Additionally, Krasnoselsky has advanced Moscow’s victim complex by attacking the West for its supposed “Russophobia.”

In recent years, Russia has exploited the Moldovan-Transnistrian frozen conflict and hindered the efforts to reach a peaceful settlement. Russian state media has broadcast anti-Moldovan propaganda to Transnistrian TVs and radios. Since the end of the war, Russia has maintained a military presence in the Transnistria, despite promising to remove its so-called “peacekeepers” in 2002. The continued presence of the Russian military in Transnistria allows Moscow to exert influence over Moldova and threaten Ukraine’s western border.

The 2003 Kozak memorandum—which was designed to settle the Transnistrian conflict—illustrates Russia’s status as a biased mediator in favor of the Transnistrian side. Moscow’s proposal would have 1) given Transnistria a de facto veto over any legislation in the Moldovan parliament and 2) allowed Russian troops to stay in Transnistria for at least 20 years. The Moldovan president, Vladimir Voronin, would have signed the memorandum if not for large-scale protests in Chișinău against the Russian plan.

The 30-year prolonging of the Transnistrian conflict by Russia has hindered Moldova’s ability to integrate militarily and politically with the West. Because of the unresolved conflict, Moldova is essentially blocked from joining NATO. This leaves little Moldova extremely vulnerable to Russian aggression.

Likewise, the lack of a full peace has made it very difficult for Moldova, Europe’s poorest nation, to join the European Union (EU). However, the European Commission recommended that Chișinău receive candidate status on June 17, 2022, marking a significant step in the country’s EU ambitions.

Transnistria’s Frozen Conflict and Russian Strategic Goals

The Transnistrian people are exploited by Russia to further Moscow’s geopolitical goals. The multi-ethnic Transnistrian population took matters into their own hands in the late 1980s and early 1990s to preserve their vision of linguistic equality and multiculturalism.

In the ensuing years, however, Transnistria has become little more than a Russian puppet state, used as a proxy to hinder the growth of Western political and economic hegemony in the former USSR. Sadly, the Transnistrian and Moldovan people are bearing the brunt of this modern iteration of the “Great Game.”

pavel karafiát)

The Ukrainian war offers new opportunities and obstacles for Transnistria, Russia, Moldova, and Ukraine. And questions remain regarding who carried out the recent string of bombings and shootings in Transnistria.

There is discussion that the events were Russia’s attempt to further exploit the Moldovan-Transnistrian split; that Russia is pushing for Transnistria to enter the Ukrainian war to take pressure off its costly, slow-moving campaign in the Donbas. But Russia isn’t the only possible culprit.

For its part, although it is possible that Moldova is hoping to exploit Russia’s preoccupation with Ukraine, it is unlikely that President Maia Sandu, who is focused on boosting the nation’s EU credentials, would choose to reignite a military dispute with Transnistria.

Ukraine too has little reason to open up a new front in the Russian war. While Russian media have blamed Ukraine for the Transnistrian bombings, the ineffectiveness of the attacks and the strange choice of targets makes it unlikely that Kyiv ordered the strikes.

For example, Transnistrian authorities claimed that a drone from “the Ukrainian side” dropped two grenades on a parking lot used by the Russian peacekeeping forces. The crude bombing only managed to shatter the windshield of a Russian transport truck. Surely a Ukrainian sabotage operation would be more effective and against a more important target.

With Moldova and Ukraine ruled out as suspects, that leaves open the possibility that the Transnistrians or Russians have staged false-flag attacks.

While the Russian puppet republics in the Donbas were quick to blame Kyiv for fabricated provocations immediately preceding Russia’s February 24 invasion, Tiraspol has remained more cautious. The Transnistrians have insinuated that Moldova and Ukraine are to blame for several of these incidents but have not accused them outright.

President Krasnoselsky has repeatedly reaffirmed the separatist region’s desire for peace and to “preserve the Transnistrian people.” Krasnoselsky was tight-lipped in a recent interview with Russian state media, stating only that the unnamed saboteurs failed to raise tensions and destabilize the self-declared state. It makes little sense why Krasnoselsky would risk the nation’s fragile independence by provoking both Moldova and Ukraine.

The Transnistrians of 1989 and 1990 were not part of a grand Russian strategy to destabilize Moldova. Rather, the protests and independence referendums in these years were grassroots efforts by a multi-ethnic population, which felt threatened by Moldovan nationalism and pan-Romanianism. Only in the years after these actions did Moscow begin to exploit the conflict. As ties with Russia increased, Russian chauvinism usurped true linguistic equality and multiculturalism in Transnistria.

Looking forward, it appears unlikely that Transnistria will become a new front in Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. Nonetheless, the bombings are a frightening reminder that Moldova is Putin’s most likely future target. It will be up to the Transnistrians to decide if they will remain fully subservient to the Kremlin or assert agency over their own future.

King, Charles. The Moldovans: Romania, Russia, and the Politics of Culture. Stanford, California: Hoover Institution Press, 1999.

Harrington, Keith. "Moldova's Rebel Region Stays Neutral in Russia's War on Ukraine." Balkan Insight. 11 March, 2022. https://balkaninsight.com/2022/03/11/moldovas-rebel-region-stays-neutral-in-russias-war-on-ukraine/

Peter, Laurence. "Transnistria and Ukraine Conflict: Is war spreading?" BBC News. 27 April, 2022. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-61233095.

King, Charles. “Moldovan Identity and the Politics of Pan-Romanianism,” Slavic Review, 53, no. 2 (1994): 345-368. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2501297.

Coyle, James J. Russia’s Border Wars and Frozen Conflicts. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-52204-3.