Underlying the 2022 war in Ukraine is another conflict, this one over the past.

In 2021, Russian President Vladimir Putin wrote a long essay entitled, “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians.” It laid out historical claims to the territory of Ukraine, walking through a specious reading of history beginning with the medieval period and moving through the Soviet Union’s dissolution in 1991.

The rest of the world was uninterested in Putin’s article and his view of history. However, while it may not be a scintillating read, it lays out his underlying rationale for the war, and thus we need to understand the history he is talking about in order to correct Putin’s false claims that Ukraine “belongs” to the modern Russian state.

Medieval history is popular when it is turned into shows such as “Game of Thrones” and “Vikings,” but that of eastern Europe rarely registers on the radars of most Americans. Ukrainians and Russians, (and Belarusians), trace their ancestry back to a medieval kingdom known as Rus. This kingdom was the largest territorially in medieval Europe, stretching from the Baltic in the north to near the Black Sea in the south.

It was centered on the Dnipro River and had its capital at the city of Kyiv. The ruling family, popularly, though anachronistically, known as the Rurikids were originally from Scandinavia but by the time of the Christianization of Rus in 988/989 CE they were firmly Slavic.

They retained contacts across the breadth of medieval Europe. Members of the Rusian (of or relating to Rus) royal family married into the royal families of England, France, the German Empire, Hungary, Poland, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) Empire, as well as concluding marriages with the nomadic peoples of the steppe north of the Black Sea. If one were to map this, it would be easy to see that the web of relations stretches across the entirety of the continent.

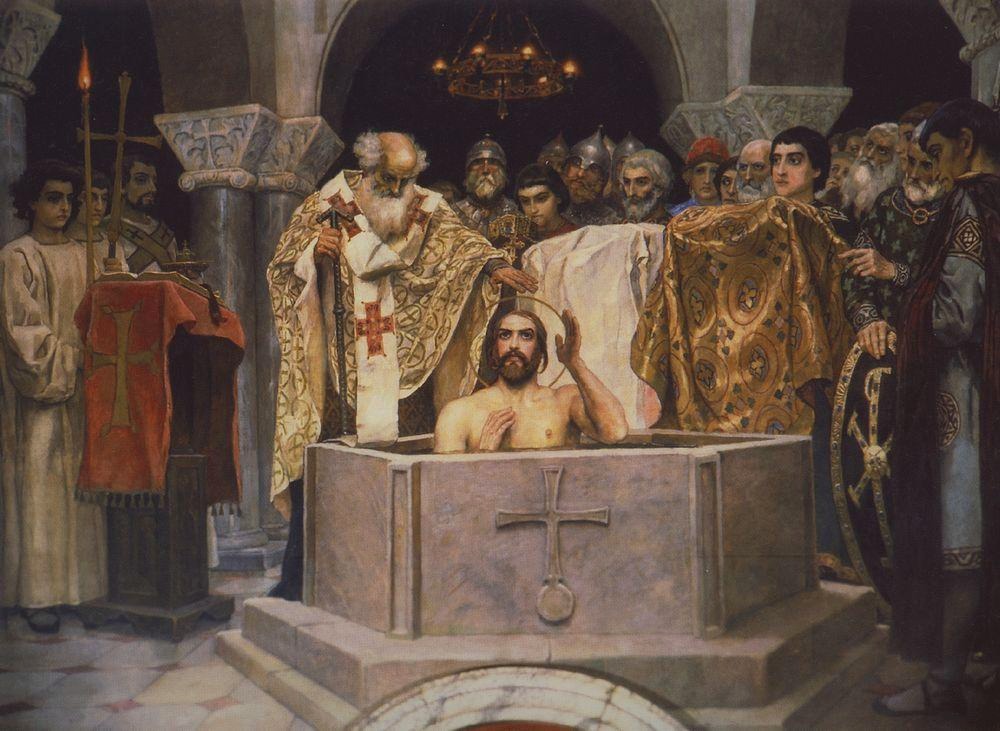

The kingdom of Rus converted to Christianity under the rule of Volodymyr Sviatoslavich as part of his marriage to the Byzantine princess in the late tenth century. This marriage has often been connected to the late fifteenth century marriage of the Muscovite ruler Ivan III to the Byzantine princess Sofia Paleologina to demonstrate a solid Byzantine connection for Rus, thus propping up the myth that the cultures and practices of Rus migrated solely to what became Russia.

However, when examined more closely the reality is a bit murkier. The connection to Byzantium did exist, but it was not exclusive, and it certainly did not place Rus into a world apart from the rest of Europe. The peoples of Rus got around, connecting the polity to the rest of Europe and to European cultures in ways Muscovite and later Russian chroniclers did not acknowledge.

Rusian pilgrims travelled to Santiago de Compostela in northern Iberia, as we see from the traditional seashell pilgrim badges found in Novgorod. A Rusian prince, Iaropolk Iziaslavich, met with Pope Gregory VII in the 1070s, who granted the kingdom of Rus to him in exchange for an oath of fealty. And a Rusian princess became the wife of the German Emperor Henry IV but left him to side with the papacy during the Investiture Controversy in the late eleventh century.

Given the ongoing war in Ukraine it is urgent to understand the history of Rus to place this conflict in its proper historical context. Two takeaways are worth noting.

The first is that Rus was part and parcel of medieval Europe. The idea that Ukraine is European is not new, and the idea that eastern Europe is not part of Europe is not correct.

The second is the simple fact that the kingdom of Rus was not Russia, neither was it Ukraine even though the core territories of the medieval kingdom are coterminous with modern Ukrainian territory. Instead, it was a medieval kingdom that could be seen as the root of all three East Slavic countries, not just one. Its history belongs to all of them collectively, at least in part, since they have all also made their own history over the nearly 800 years since the kingdom of Rus lost its functional unity.

The Russian government’s rationale for the war in Ukraine is not about oil, coal, or natural resources. It is about asserting specious historical claims. Those claims are broadcast widely in Russia and have been widely accepted.

For instance, a Russian soldier, in the fourth week of the war, evicting Ukrainians from an apartment in Irpin, a suburb of Kyiv, told them that he was repossessing the territory of Rus for Russia. This ordinary soldier tells us so much about what Putin wants and why.

Understanding the context of the situation, and caring about history ourselves, may help us better deal with Putin’s war and his ideas about what happens next.

![]()

Learn more:

Christian Raffensperger, Reimagining Europe: Kievan Rus' in the Medieval World (Harvard UP, 2012)

Christian Raffensperger, Ties of Kinship: Genealogy and Dynastic Marriage in Kyivan Rus' (Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute, 2016)

Serhii Plokhy, The Origins of the Slavic Nations: Premodern Identities in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006)

Yulia Mikhailova, Property, Power, and Authority in Rus and Latin Europe, ca. 1000-1236 (Leeds: ARC Humanities Press, 2018)