Belarus has been called Europe’s last dictatorship, but ongoing protests in the wake of the disputed August 2020 Presidential elections have posed the most serious threat yet to the regime of Alexander Lukashenko. This month, historian Stephen Norris sketches the history of Belarus and examines how demonstrators, online activists, and artists are seeking to redefine Belarusian politics, nationalism, and identity.

Protests continue to sweep across Belarus. By the end of 2020, more than 30,000 people had been arrested, a staggering figure that one human rights organization rightly referred to as unprecedented repression in the country’s history. More than five months after President Alexander Lukashenko claimed victory in a fraudulent election, his opponents have not given up.

The Belarusian opposition leader Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, 2020 (left). A banner in Minsk stating the date of the 2020 presidential election (middle). Alexander Lukashenko has been the president of Belarus since 1994 and recently claimed victory in a fraudulent election (right).

“I cannot understand how we could stop when people have suffered and continue to suffer,” one woman participating in December’s protests said. “We cannot close our eyes to this.” Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, the opposition leader who claimed victory in the August elections, declared, “Each march is a reminder that Belarusians will not surrender.”

While the size and duration of the protests might be surprising, they stem from frustrations that have built up over the years and that have been exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In August, after sham elections, Alexander Lukashenko, the authoritarian president of the country since 1994, declared victory and the start of his sixth term in office. After a quarter century in power and previous electoral frauds, many in Belarus had had enough.

Lukashenko again barred international election monitors from observing the election. But grassroots organizations were more prepared than ever to cover widespread fraud, publishing evidence of it across social media. This flow of information also reflects important shifts within Belarus, especially the massive growth in internet access. In 2010, only a third of the population had it, while a decade later that proportion had reached nearly four-fifths.

A greater number of people want more from the government, and the Lukashenko system has proven unable to respond to these demands.

Throw in a stunningly poor response to the coronavirus pandemic—Lukashenko had dismissed the virus as a form of “psychosis” and suggested a good shot of vodka would ward it off before contracting it himself—and you have the recipe for resistance.

The immediate protests in August were the largest in the history of Belarus. Since then, the protestors’ tactics have evolved, with marchers now participating in smaller demonstrations across the country, but their aims have not wavered.

Initially, the protestors carried two different flags that symbolized Belarus’s history, but after the first week of taking to the streets, one of these flags became more central to the anti-Lukashenko opposition: a white flag with a red horizontal stripe.

Since August, protestors and artists have enlisted historical symbols and revised historical memories in their attempt to change their system.

The flag’s history and the evolution of how it functions as a national symbol help us understand the sustained protests. So too do Tikhanovskaya’s words, which reference a fundamental notion of what it means to be Belarusian.

A Bit about Belarus

The protests in Belarus have brought the country into the international limelight, but Belarus remains largely unknown to Americans. And yet, as one of its leading historians, Per Anders Rudling, has written, Belarus has a population larger than his native Sweden, larger than the three Baltic republics (PDF File) combined, and larger than Austria. It would be the 11th largest U.S. state.

A map of the administrative divisions of Belarus.

Modern Belarusian nationalism was one of the most recent to appear in Europe.

The first Belarusian language newspaper appeared only in 1906. Branislaŭ Taraškievič, a crucial figure in the development of a Belarusian national consciousness, popularized the Belarusian language in 1918 by writing a grammar book, which was published in several editions. Arkadź Smolič’s map of Belarusian dialects, which charted the regional scope of Belarusian identity, appeared in 1919.

Political mobilization for Belarusian independence, dominated by agrarian socialists, developed along similar chronological parameters, kickstarting after the 1905 Revolution swept through the Russian Empire.

Because modern Belarusian nationhood followed this path, the imagined community of Belarus, more than any other European country, has been shaped by the 20th century and the era of the world wars.

Like its neighbor Ukraine, Belarus started the 20th century with a largely rural population, albeit one not split across the Habsburg and Romanov empires. Like in Ukraine, the first stirrings of modern nationhood were shaped by the Russian imperial view that Belarusians were not a separate nation, but a less evolved group of fellow Russians (White Russians or West Russians).

Like in Ukraine, Belarusian lands had once formed part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, providing a relatively recent history separate from Russia that Belarusian nationalists could embrace.

The Great War that began in 1914 brought German occupation of Belarusian lands, which in turn jumpstarted an independence movement. When German forces arrived in the region, they were surprised to discover a people they had never heard of, and soon figured out by a process of elimination that they were not Lithuanian, Polish, or Russian.

The German occupation regime lifted imperial Russian censorship and the ban on using Belarusian language; the grammar book and dialect map appeared in these circumstances.

The passport of the Belarusian People's Republic featuring the Pahonia, 1918 (left). A stamp from the Belarusian People’s Republic, 1918 (right).

As the Eastern Front of the war grew more chaotic after the Bolshevik seizure of power in October 1917, Belarusian independence movements seized on their chance.

On March 25, 1918, just 22 days after the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk took the new Bolshevik state out of the war, a coalition of political movements announced the creation of the Belarusian People’s Republic [BNR]. It was intended to be independent, oriented politically toward the dominant agrarian socialists, but decidedly not Bolshevik.

The Republic lasted one year before being caught in the midst of the Soviet-Polish War and then swallowed up with the establishment of the USSR in 1922 (the Bolsheviks had first created a Belorussian SSR in 1920).

Belarus is thus one of many former Soviet republics that tend to get defined by their historical relationship to their much larger neighbor, Russia. It is also often seen as the closest to and most assimilated within Russia.

This situation has led some Belarusian academics, including the philosopher Valiancin Akudovic, to argue that the primary predicament for articulating modern Belarusian nationhood is its domination by silences, absences, and empty signs.

Much more could be said about this history. It matters most in 2020 because the protests ended these silences and filled in the meaning of old symbols. Protestors wielded the flag of the BNR, one with a white background and a horizontal red stripe in the middle. The official BNR state emblem, the Pahonia—a knight on horseback—was originally a symbol of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

The BNR as a political entity might not have lasted very long, but these symbols proved durable, often serving as emblems of independence during the Soviet era.

When Belarus declared its independence from the USSR in 1991, the new Belarusian state initially restored the BNR flag and state emblem. In 2020, protestors turned to them again as a means to challenge Lukashenko’s embrace of Soviet-era symbols, thus infusing them with new meaning once more.

The War and the Weight of Traumatic History

When Tikhanovskaya declared that Belarusians would never surrender, she evoked the central component of modern Belarusian nationhood: resistance in the Second World War.

Much can be (and has been) written on this subject, but the most striking fact remains the death toll: 2.29 million Belarusians, or just over one-quarter of the population perished (by way of comparison, approximately 1.3 million Americans have died in all wars since 1776).

Belarus, the historian Timothy Snyder writes in his book, Bloodlands, was the “center of the confrontation between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, with the capital city of Minsk its epicenter.” Between 1941 and 1944, Snyder concludes, Belarus was “the deadliest place on earth.”

The Kholm Gate at the Brest Fortress (left). A wide view of the Courage Monument, constructed in 1971, at the “hero fortress” in Brest, Belarus (right).

After the war ended, the Soviet state enshrined the Belarusian wartime experience in a series of monumental complexes. The Brest Fortress, where Red Army forces held out even while the Wehrmacht advanced deep into Soviet territory, was named a “hero fortress”; in 1965.

Six years later, a massive memorial complex opened, complete with a 100-foot stone sculpture of a soldier entitled “Courage.” In the destroyed village of Khatyn, just over 30 miles from Minsk, the Soviet state unveiled a national memorial in 1969 to the victims of the 1943 massacre there perpetrated by a Nazi police battalion.

The complex contains a “cemetery of villages” with 185 tombs and a statue called “Unbowed Man,” of Yuzif Kaminsky, Khatyn’s only adult survivor, holding the body of his dead son.

The “Unbowed Man” statue shows Yuzif Kaminsky, Khatyn’s only adult survivor, holding the body of his dead son (left). Cemetery of Villages in Khatyn with 185 tombs. Each tomb symbolizes a particular village in Belarus that the Nazis burned. (right).

Just outside Minsk, which was named a “Hero City” in 1974, a “Mound of Glory” consecrated in 1969 commemorates the liberation of the city by Red Army forces in 1944.

Collectively, these and other Belarusian memorials to the war continue to speak to the courage, resistance, sacrifices, and suffering associated with the war, all essential components of the larger Soviet narratives about victory.

Lukashenko has rebuilt a cult of the war, though a specifically Belarusian version of it. The Belarusian dictator has revitalized the memorial sites and has dedicated other memory sites, including a new one at the former extermination camp at Maly Trostenets.

Like his Russian counterpart, Vladimir Putin, Lukashenko relishes the annual Victory Day parade festivities held every year on May 9. This year Lukashenko went ahead with a large one to mark the 75th anniversary of the war’s end despite the coronavirus pandemic. In his speech, he acknowledged it was a “difficult time,” but thundered, “Our current difficulties are obscured by the hardships and losses that befell the heroic generation that saved the world from the Brown Plague.”

In promoting the Victory so thoroughly, the Lukashenko regime has highlighted actions that its political opponents have found useful. Belarusian protestors have adopted the language of “fascists,” “resistance,” and “heroism.”

“We were brought up on endless films and books about fighting the fascists, and then, when you look at the uniforms, the style, the methods used by the authorities, it’s not hard to see why these memories resonated,” said Yulia Chernyavskaya, a Belarusian cultural anthropologist.

A lone protestor holds the BNR flag in front of a police line in Minsk, 2020.

The myth of the “partisan republic,” as the scholar Simon Lewis has written, has persisted, but has increasingly been challenged, particularly as Lukashenko revived the war’s mythology.

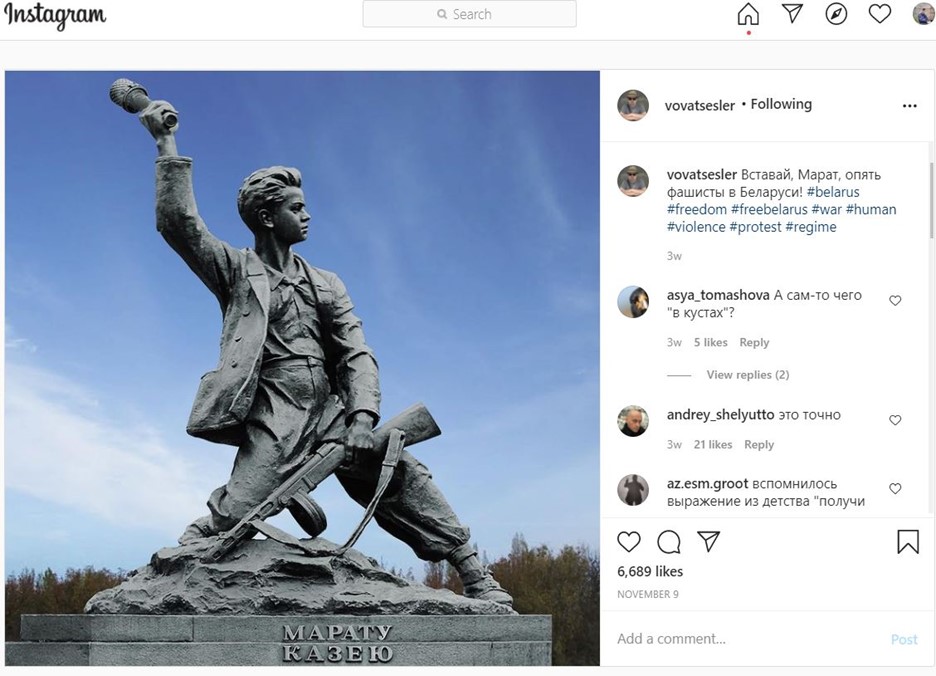

The artist Vladimir Tsesler also challenges these notions in his Instagram works. A prominent Belarusian designer and graphic artist, Tsesler has gained a massive social media following in the wake of the August protests.

One recent post consists of a picture of the Marat Kazei monument in Minsk. Kazei joined the partisan movement in World War II and died after sustaining multiple injuries in a skirmish with Nazi forces. As he lay wounded, with enemy troops moving toward him, Kazei pulled the pin on a grenade, killing himself and his enemies. He was 14 years old.

Tsesler’s invocation of Kazei’s actions comes with the words: “Rise up, Marat, there are fascists in Belarus again!”

The protestors and the art of protesting have collectively stripped the meanings of the war away from Lukashenko’s version of it and made it more democratic: the idea of patriotic resistance, captured in the notion of a “partisan gene,” has returned to the streets.

More and more Belarusians have adopted the language the Lukashenko regime has used about the war and added their own voice to it, turning against the state.

Svetlana Alexievich, the Nobel Prize winning author who has long documented the voices of people silenced in official histories, fears that her fellow Belarusians have not yet developed a way to combat Lukashenko’s Stalinist-style methods. Victory in World War II, she has noted, meant Belarusians “developed an ingrained vaccine” against fascism, “but we don’t have any medicine to protect us from the Gulag and Stalin.”

Certainly, the protestors and the artists who have helped define the protests are trying to inoculate themselves.

Both Tsesler and Alexievich joined Tikhanovskaya’s Opposition Coordinating Council. Tsesler even paid tribute to Alexievich’s moral authority after her August arrest, creating a virtual memorial plaque stating that “in this building Nobel laureate Svetlana Alexievich was interrogated on August 26, 2020.”

Another Tsesler image connects the Lukashenko regime with the Stalinist: in it, the state coat of arms, the one Lukashenko took from the Soviet era, comes emblazoned with the dates 1994-1937. In Tsesler’s vision, the Lukashenko era, which began in 1994, has gone backward, not forward, taking the country back into the climate of Stalin’s great purges.

Vladimir Tsesler. Reboot. From the artist's Instagram page. Used with permission.

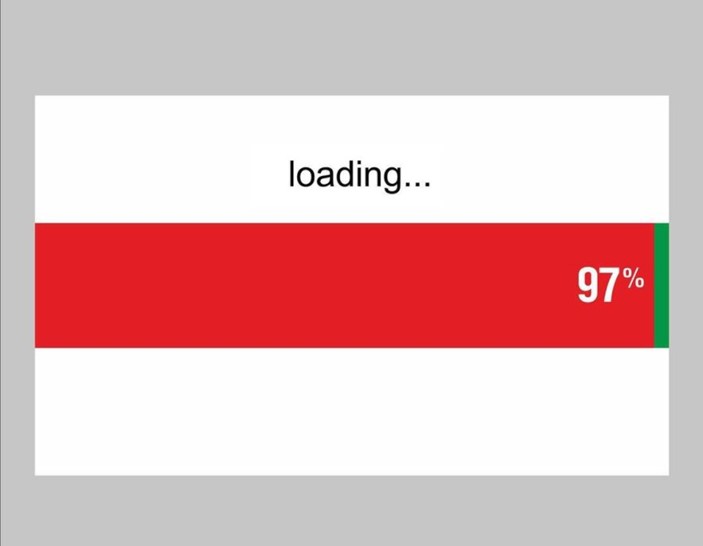

Tsesler’s art of protest contains seeds of hope too. One image has the historic red-and-white flag “loading” over the current green and red flag, a process that is 97% complete. The number is not without symbolism too: it refers to Charter 97, a declaration for democracy in Belarus (which itself was a reference to the famous Charter 77 in Czechoslovakia).

A Color(ful) Revolution: Symbols and History

Lukashenko has managed to win previous elections by “disappearing” opponents, having them arrested and beaten, and/or forcing them into exile. When elections were held and Lukashenko was declared the winner, protests broke out; but police would then break up the protests.

The 2020 election followed this established narrative. Three main opposition candidates announced their intentions to run against Lukashenko: two were arrested, another excluded.

What followed next marked an important difference.

Svetlana Tikhanovskaya registered and became the consensus protest vote. She is a former English teacher and the wife of one potential candidate who is currently under arrest, a popular blogger and YouTuber named Sergei Tikhanovsky. Veranika Tsapkala, the wife of an exiled opposition leader, and Maria Kalesnikava, the campaign manager of another presidential candidate, joined Tikhanovskaya.

Lukashenko did not take the women seriously, repeatedly saying they had no place in politics. In an interview shortly before the election, after dismissing his opponent as someone who had just cooked and put the children to bed, Lukashenko concluded: “And now there’s supposed to be a debate about some issues.”

Clearly, he underestimated the women in his country. Before the elections, Lukashenko declared that the constitution was “not meant for a woman” and then “clarified” this statement by stating he did not think a woman could handle the responsibilities of the presidency.

One of the first symbols of anti-Lukashenko opposition in 2020 came in the form of a painting of a woman, Chaim Soutine’s Eva. Soutine was born in 1893 in Smilavichy, near Minsk, but emigrated to France in 1913. The wealthy banker and philanthropist Viktar Babaryka purchased Eva in 2013 as part of his ongoing efforts to “repatriate” Belarusian artworks. In May 2020, Babaryka announced he would run against Lukashenko and quickly gained popularity.

True to form, the Lukashenko government arrested Babaryka and charged him with financial crimes, including an alleged attempt to smuggle his paintings out of the country. When news broke, Belarusians turned Eva into a meme, depicting her in jail and dressed in prison garb, among other uses of her image.

Belarusian women thus acted as important political and symbolic leaders in the protests.

Lukashenko has also proven retrograde in his use of history. A former Red Army soldier, collective farm head, and Communist Party member, he swept to power in 1994 after widespread disillusionment with the first wave of post-Soviet reforms. A year later, Lukashenko oversaw a referendum to restore the Soviet-era flag and emblem of Belarus, one officially established in 1951, a bicolor flag with two-thirds green and one-third red.

Over time, what was once a Soviet-era symbol became associated with Lukashenko. The red-and-white symbol came to symbolize opposition to the dictator. As the former BNR flag became more visible in anti-Lukashenko protests, the Belarusian leader played up its use during World War II by Belarusian collaborators, thus ignoring its earlier use.

Belarusian artists also engaged with the clash over these historical symbols during the protests. The artist Vladimir Tsesler has posted numerous representations of Belarusian flag symbolism on his Instagram page, turning Lukashenko’s version of the two flags’ meanings on their head. Tsesler’s reimaginings of the red and white flag invoke positive emotions: a red heart appears in the middle of one flag while in another, the red line consists of a line of protesters.

By contrast, the green and red Soviet-era emblem is cast in entirely negative tones. The colors peek out from under a balaclava worn by a policeman in one of his images; in another, a policeman’s baton consists of a red handle and green end. The starkest version of all has the Lukashenko green and red flag hanging on a clothesline, drenched in blood.

Vladimir Tsesler. Do not wash. From the artist's Instagram page. Used with permission.

Tsesler has taken the historical associations connected to these symbols and placed them within the context of the ongoing protests. The black and white, good versus evil conflict is red and white versus red and green.

One of the most striking examples of how internet art has flourished and how it has reappropriated the red-and-white flag into the symbol of opposition to Lukashenko can be found in the online “Museum of Flags.” Every region, every city, every region within a city, every diasporic region, and much, much more (even Pierce Brosnan): all have their own version of the red-and-white flag, many of them created by Tsesler.

Rufina Bazlova’s striking work, also on Instagram, makes powerful use of traditional Belarusian folk colors in the form of vyshyvanka, traditional embroidery, weaving in scenes of protest, violence, and historical allusions. Bazlova’s entire cycle is called “The History of Belarusian Vyzhyvanka,” a pun on the words “embroider [the vyshyvanka]” and “survive [vyzhyvat’].”

Rufina Bazlova, Svetlana is My President. From the artist’s Instagram page (left). Rufina Bazlova, Demonstration. From the artist’s Instagram page (right). Both used with permission.

As she has stated, “Belarusian vyshyvanky are a specific code for recording information about the lives of people, the nation, and whoever wears the embroidery. It is a sort of coded history of the people.” As to the project that involves the pun, Rufina puts it best: “This is what my people are doing, they are surviving.”

The author thanks Sasha Razor for reading a draft version of this article.

On the initial protests:

Bekus, Nelly. “The Crackdown in Belarus” Tribune 13 August 2020.

Gessen, Masha. “After a Rigged Election, Belarus Crushes Protests Amid an Information Blackout.” New Yorker 12 August 2020.

Razor, Sasha. “The Lesson of Belarus.” Los Angeles Review of Books 18 August 2020.

On the history of Belarus:

Beorn, Waitman Wade. Marching into Darkness: The Wehrmacht and the Holocaust in Belarus. Harvard University Press, 2014.

Gapova, Elena. “The Woman Question and National Projects in Soviet Byelorussia and Western Belarus (1921–1939)” in J. Gehmacher, E. Harvey, S. Kemlein eds., Zwischen Kriegen. Nationen, Nationalismen und Geschlechterverhältnisse in Mittel- und Osteuropa, 1918-1939

(Osnabrück: fibre-Verlag, 2004): 105-128.

Rudling, Per Anders. "The Beginnings of Modern Belarus: Identity, Nation, and Politics in a European Borderland: 2015 Annual London Lecture on Belarusian Studies." Journal of Belarusian Studies 7, no. 3 (2015): 115-127.

________. The Rise and Fall of Belarusian Nationalism, 1906–1931. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2015.

Walke, Anika. Pioneers and Partisans: An Oral History of Nazi Genocide in Belorussia. Oxford University Press, 2015.

On historical memory:

Lewis, Simon. "The “Partisan Republic”: Colonial Myths and Memory Wars in Belarus." In War and Memory in Russia, Ukraine and Belarus. Palgrave Macmillan (2017): 371-396.

Marples, David R. "History, Memory, and the Second World War in Belarus." Australian Journal of Politics & History 58, no. 3 (2012): 437-448.

________. 'Our Glorious Past': Lukashenka's Belarus and the Great Patriotic War.Ibidem, 2014.

Mort, Valzhyna. Music for the Dead and Resurrected: Poems. FSG, 2020.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. "Postcolonial Estrangements: Claiming a Space between Stalin and Hitler." In Rites of Place: Public Commemoration in Russia and Eastern Europe. (2013): 285-315.

Rudling, Per Anders. "The Khatyn Massacre in Belorussia: A historical controversy revisited." Holocaust and Genocide Studies 26, no. 1 (2012): 29-58.

________. "“Unhappy Is the Person Who Has No Motherland”: National Ideology and History Writing in Lukashenka’s Belarus." In War and Memory in Russia, Ukraine and Belarus, Palgrave Macmillan, 2017: 71-105.

On gender and nationhood in Belarus:

Gapova, Elena. "On nation, gender, and class formation in Belarus… and elsewhere in the post-Soviet world." Nationalities Papers 30, no. 4 (2002): 639-662.

________. "Things to Have for a Belarusian: Rebranding the Nation via Online Participation." Digital Icons 17 (2017): 47-71.