Ask someone to describe the Soviet Union during the Second World War and they will conjure up images of beleaguered Red Army soldiers at Stalingrad, the mechanized carnage of the tank battle at Kursk, or Stalin alongside Roosevelt and Churchill at Tehran, Potsdam, and Yalta. The triumph of the Red Army on the Eastern Front, alongside the Soviet Union’s rapid industrialization and reorganization following early losses in the war, helped rescue the countries of Europe from the domination of Nazi Germany and its allies.

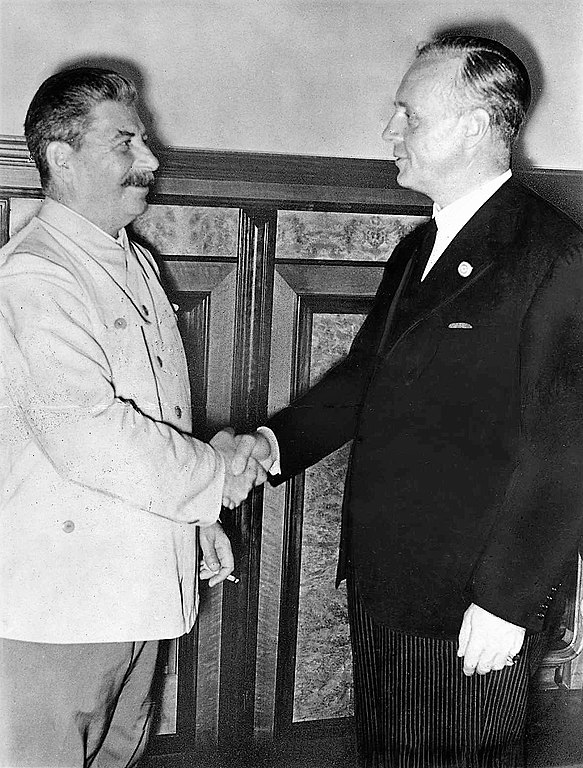

Yet it was the Soviet Union who emerged in the early days of the Second World War as Nazi Germany’s key ally. The signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union in August 1939 sealed the fate of the Polish nation and cast Europe further into darkness.

The invasion and partition of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union in September 1939 shocked the world and set the stage for the German invasion of France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands the next year.

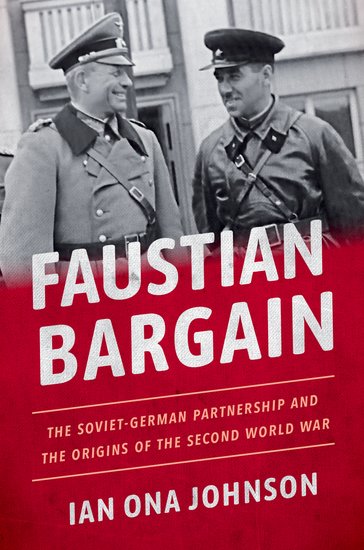

It is the relationship between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany that Ian Ona Johnson examines in his new book Faustian Bargain.

The book chronicles how the relationship between these two powers was not merely a short-term opportunistic alliance in 1939, but part of a longer pattern of Soviet-German cooperation during the interwar period. Johnson splits his monograph into two parts. The first part ranges from 1918 to Hitler’s rise to power in 1932, seeking to determine why the Soviet Union and Germany decided to work together and how their partnership took shape.

The second part of the book begins in 1933 and ends with the preparations for the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941. This part of the book focuses on the consequences of the German-Soviet relationship, detailing how the rise of Nazi Germany initially cast aside the vital partnership then rekindled it when Nazi Germany set its sights on Eastern Europe.

The most critical questions asked by Johnson concern how these two countries, frequently at odds with each other ideologically and militarily, were able to convince each other that an exchange, and eventually alliance, was feasible. Johnson examines the major events and themes that dominated the relationship between these two powers between 1918 and 1941 in 35 short chapters.

These chapters, ranging from four to nine pages each, proceed in a chronological order and provide readers bite-sized analyses of complex political, social, and military affairs. For example, he details the military and technological exchanges between the two powers throughout the interwar period. Johnson argues that early interactions and exchanges between first Weimar Germany (later Nazi Germany) and the Soviet Union paved the way for both the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact and the ideological acrimony that led to the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941.

The difficult balancing of ideological animosity and political opportunity is a central theme of Johnson’s work. Each side believed their own system superior to the other, yet each saw opportunities too tempting to ignore. For the Soviet Union, Germany offered desperately needed expertise for its military and industrial sectors. For Germany, the Soviet Union became a means to undermine the Treaty of Versailles by engaging in a partnership that led to rearmament.

The technological component of Soviet-German cooperation stands out as its most significant element. Johnson’s work emphasizes this factor by examining the shared military facilities and military-industrial plants jointly staffed by the two countries, as well as the exchanges of training and expertise that undergirded the relationship. These exchanges proved invaluable in shaping the militaries of both nations prior to the Second World War.

Sprinkled throughout Johnson’s account are a wide cast of historical actors and organizations that came to prominence during this period. Familiar faces like Lenin, Stalin, Molotov, Hindenburg, Hitler, and Ribbentrop are all present. However, it is the presence of other, less familiar figures that gives Johnson’s book the feel of a novel.

Military leaders like Johannes von Seeckt, whose pro-Russian influence on the German military had a pronounced effect on the partnership between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, become essential characters in this narrative. Johnson’s focus on the technological exchanges between Germany and the Soviet Union allows the tanks, planes, guns, and tactics swapped between the two nations to emerge as a central component of his research as well.

Enthusiasts of German or Soviet tank tactics, airplane design, and the many other technologies of warfare will enjoy Johnson’s tracing of their origins from this period. Johnson attributes the designs of the Soviet Union’s famous T-series tanks as a partial result of the Soviet-German partnership. Similarly, Johnson demonstrates how the Luftwaffe’s wartime aviation tactics were in part the result of trials conducted in the Soviet Union. Through his tracing of these technologies, Johnson finds ample means of demonstrating the very real technological and operational outcomes of the difficult German-Soviet relationship.

Johnson concludes that it was rearmament that stood as the central obstacle to Germany’s interests in a new war. He demonstrates the essential role that the Soviet Union played in achieving Germany’s goals of breaking free of the shackles of Versailles by allowing it to skirt the provisions of the treaty.

Johnson worked in twenty-three archives and three languages to unveil the tumultuous relationship of these rival European powers. His work is sure to be of interest to readers who want to understand the relationship between the Soviet Union and Germany, a relationship Johnson argues is far more complex than a simple moment of political and military opportunism that emerged in 1939.

While some readers may find the short, somewhat choppy, chapters jarring at points, the episodic nature of Johnson’s account helps to underscore the ever-changing nature of the relationship between these two powers. Johnson’s analysis succeeds by reminding readers that there is no historical period, no matter how well-trodden, that cannot be served by another examination using fresh sources and a new perspective.