For over 40 years, the Cold War dominated the world's headlines and provided the backdrop for almost everything. Then, in 1991, the Soviet Union dissolved. It was replaced by a much smaller Russian Federation and the former Soviet Socialist Republics became independent nations. The West celebrated its seeming triumph and some even declared "the end of history." This month historian David Hoffmann looks back on those events and finds the seeds of the hostility between Russia and the West that has replaced the Cold War.

In 1985, it seemed the Soviet Union would last forever.

Its Communist Party rulers held a monopoly on political power. They controlled all the country’s economic resources through an enormous state bureaucracy. They wielded an extensive security apparatus backed by pervasive surveillance and forced labor camps. And they commanded the largest military in the world.

The Exhibition of Achievements of National Economy (VDHKh), Moscow, 1980.

But just six years later, in December 1991, the Soviet system came crashing to the ground—its Marxist-Leninist ideology rejected, its socialist economy scrapped in favor of capitalism, and its empire broken apart into fifteen independent countries.

How did such a powerful empire come to such a rapid demise?

Making the Soviet collapse even more perplexing is the fact that Western specialists failed to predict it. Sovietologists in the mid-1980s saw no possibility that the Soviet Union would change, let alone disappear. Conservative commentators postulated that the Soviet system was incapable of reform, and that it could only be altered through overthrow by an external force—an implausible prospect given the Soviet military’s vast nuclear arsenal.

On the contrary, change to the Soviet system deep enough to destroy it came from within the Communist Party itself.

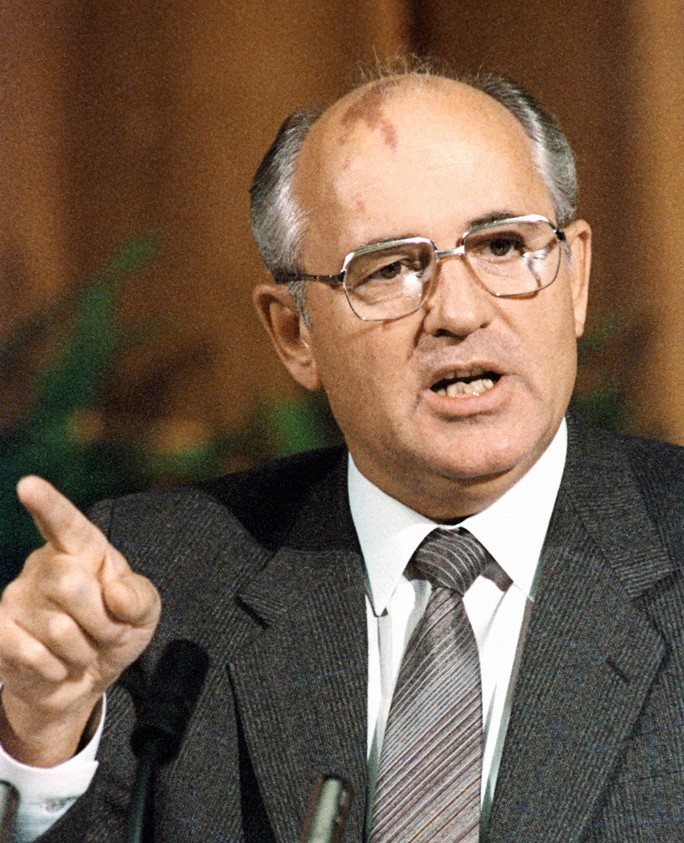

Mikhail Gorbachev became the new leader of the Soviet Communist Party in March 1985. Within three years, he launched sweeping political and economic reforms, relaxing censorship, decentralizing the economy, and democratizing the political system. In the spring of 1989, he even permitted contested elections for seats in the Soviet parliament.

Gorbachev proved willing to risk fundamental reforms to the Soviet system, even though these reforms weakened and ultimately destroyed his own power.

Gorbachev’s Reforms

To understand why Gorbachev undertook these reforms, it is important to recognize that he represented a new, more idealistic generation of leadership. The country’s previous leaders, first and foremost Leonid Brezhnev, had come of age as young Party officials during World War II. Accordingly, they took a hardline approach to governance, emphasizing hierarchy, coercion, and centralization.

Gorbachev, by contrast, had only been a boy during the war, and had instead come of age during the “Thaw” (1956-1964)—Nikita Khrushchev’s reform effort in which he denounced Stalinist repressions and sought a more humane form of socialism. Many rising Party officials of Gorbachev’s generation had been disappointed when Brezhnev ousted Khrushchev and replaced nascent reforms with rigid controls that resulted in political and economic stagnation.

A postage stamp from the Soviet Union promoting perestroika, 1988.

Gorbachev once recounted a 1984 conversation he had with his future foreign minister, Eduard Shevardnadze. Discussing the population’s disillusionment, they agreed that communist dreams of abundance and equality had become nothing more than empty slogans. Only fundamental reforms could reawaken people’s belief in communist ideals. According to Gorbachev, they settled on a very simple formula—perestroika (restructuring), glasnost’ (openness), and democratization.

The restructuring of the state-run economy would encourage initiative and raise productivity. Openness, through a lifting of censorship, would eliminate bureaucratic corruption. And democratization would give people a voice in government and overcome their apathy and cynicism. The idealism of Gorbachev and his fellow reformers prompted these changes that unintentionally shattered the Soviet system.

Not all Soviet elites were so idealistic. Elements within the Soviet bureaucracy, military, and KGB were primarily concerned with maintaining power. But initially they went along with Gorbachev’s reforms due to the dismal state of the Soviet economy.

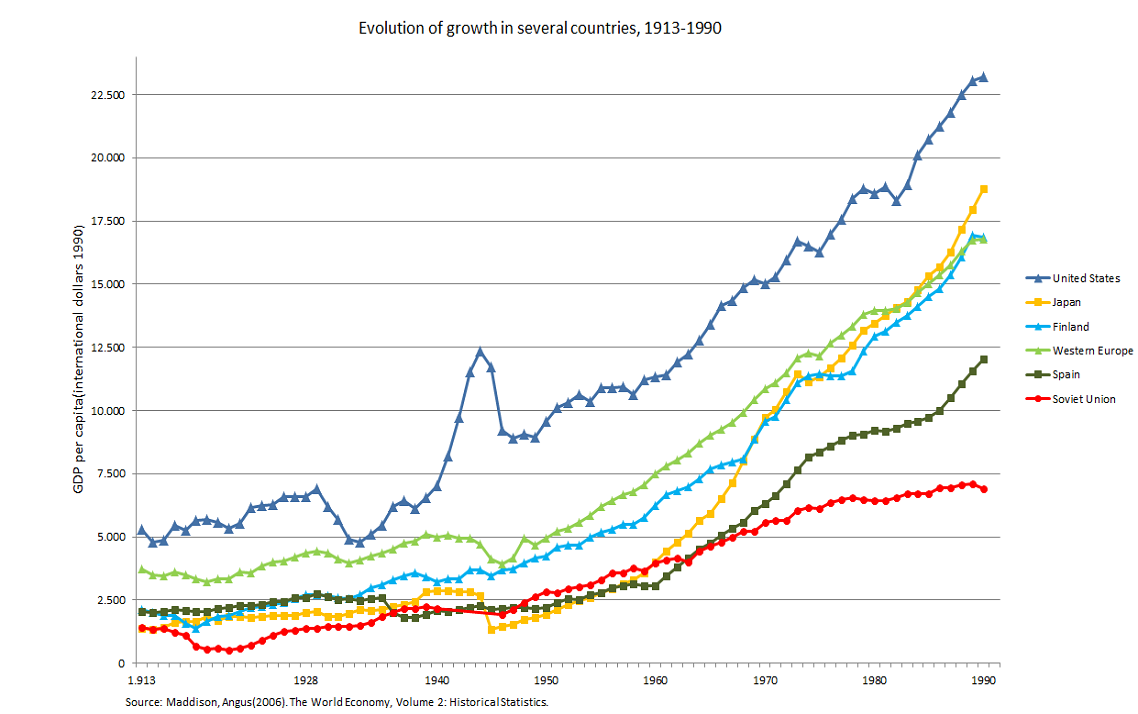

During the 1930s, the Soviet planned economy had effectively mobilized labor and raw materials for large industrial projects. But this state-run economy had never been efficient, and beginning in the 1960s, Soviet economic growth slowed as the world economy moved into the post-industrial era. Electronics, computers, and telecommunications now became key areas of development. These new sectors relied on innovation and the free flow of information—precisely what the Soviet system lacked, given its emphasis on centralization and secrecy.

For a time, oil reserves in Siberia propped up the Soviet economy, but with the sharp drop in world oil prices during the1980s, Soviet economic growth ground to a halt. By 1983, Soviet GDP had fallen far behind that of the U.S., and it was also surpassed by the GDP of Japan, a country with far fewer human and natural resources. Faced with such dire economic prospects, even conservative Soviet officials followed Gorbachev’s reforms in hopes of reviving their country’s economic and technological development.

Gorbachev’s reforms included a new approach to foreign policy. In the early 1980s, Ronald Reagan’s anti-Soviet rhetoric and arms buildup exacerbated Cold War tensions. Quite predictably, Brezhnev and his fellow leaders responded with their own arms buildup, perpetuating the nuclear arms race that had gone on for decades.

But in 1986, Gorbachev tried a new approach at a summit meeting with Reagan in Reykjavik, Iceland where he proposed radical cuts to nuclear stockpiles. While the two sides reached no accord in Reykjavik, Gorbachev’s proposals paved the way for subsequent arms control agreements and the end of the Cold War.

Negotiations at the 1986 Reykjavik Summit between Reagan and Gorbachev.

Gorbachev also adopted a new approach to Eastern Europe, stating that countries there were entitled to self-determination without fear of Soviet interference. In 1989, a series of revolutions in Eastern Europe swept Communist governments out of power and the Berlin Wall was torn down.

Conservative Backlash

Gorbachev’s reforms had gone too far for Soviet conservatives. They saw the relinquishing of Eastern Europe—land won by the blood of Soviet soldiers in World War II—as tantamount to treason. They pressured Gorbachev to slow domestic reforms and in 1990 forced him to accept hardliners into his cabinet.

At the same time, reformers criticized Gorbachev for not going far enough. Chief among these critics was Boris Yeltsin, himself a former Communist Party boss now turned radical reformer. Yeltsin garnered enormous popularity by denouncing Party privileges and Gorbachev’s “half-measures” during this period of worsening economic shortages. Far from renewing the population’s faith in the Soviet system, openness and democratization unleashed a torrent of criticism and calls for the end of Soviet rule.

Particularly fervent was unrest among national minorities that threatened to break apart the Soviet Union. Leaders in Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania (PDF File) demanded independence, while nascent political parties in some other republics also used new freedoms to demand greater autonomy from Moscow.

Caught off guard by nationalist separatism, Gorbachev belatedly negotiated a new union treaty that offered republics limited autonomy in return for their willingness to remain part of the Soviet state. Hardliners realized that once autonomy was granted, it would be far harder to reassert central control.

The August Coup

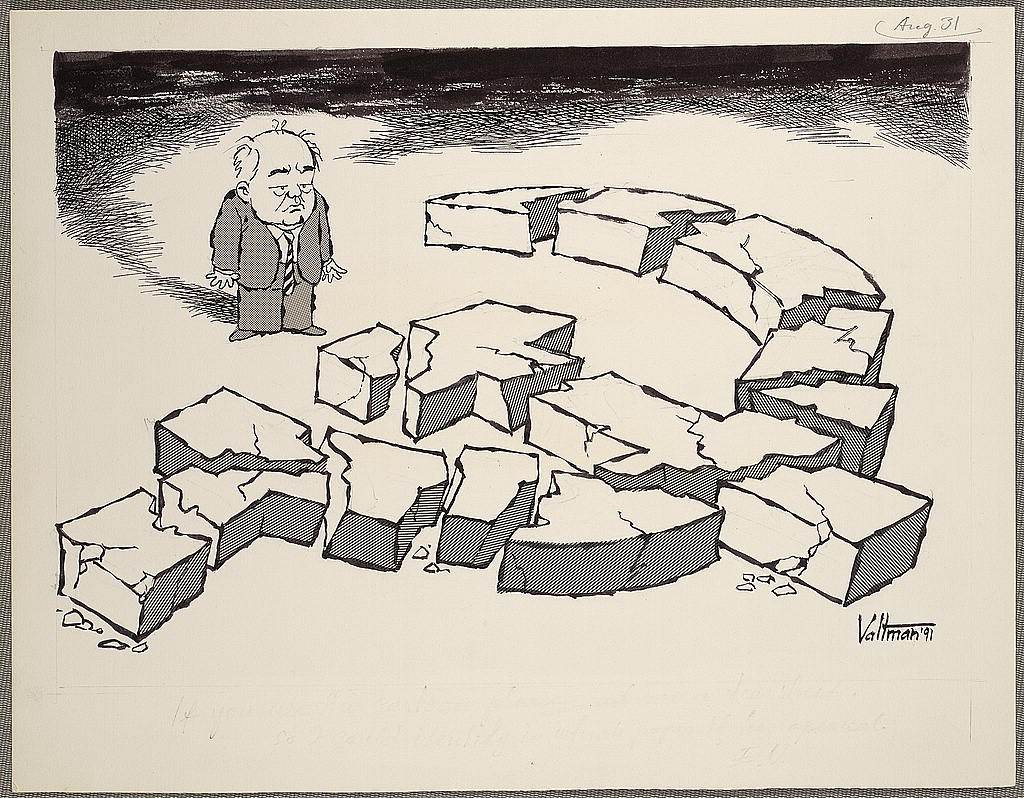

On August 19, 1991, one day before the new union treaty was to be signed, Communist hardliners launched a coup attempt to abolish Gorbachev’s reforms. They declared a state of emergency, placed Gorbachev under house arrest in Crimea, and sent tanks onto the streets of Moscow.

But the hardliners quickly encountered resistance.

Yeltsin strode out of the Russian parliament building, clambered atop one of the tanks surrounding it, and denounced the state of emergency as “a right-wing, reactionary, unconstitutional coup.” Several thousand citizens gathered in front of the building to build barricades and defend democratic reforms. While these protesters made up only a small fraction of the country’s population, their resistance had enormous symbolic importance.

The coup attempt was based not on the use of force but rather on a show of force—hardliners mistakenly assumed that tanks on the streets would cow the population into submission. Encountering popular resistance, the coup leaders soon discovered that they could not impose their will. They issued dozens of orders that bureaucrats and military officers refused to carry out. Central authority had disintegrated to such a degree that the old Soviet order could not be restored.

Within three days the coup attempt failed, and its leaders were arrested. Gorbachev returned to Moscow, but there he found a profoundly changed political landscape. Yeltsin, not Gorbachev, was the hero who had defeated the coup; Russians saw Yeltsin as their new leader. Gorbachev, meanwhile, further lost support by continuing to defend the Communist Party, whose hardline leaders (members of his own cabinet) had perpetrated the coup.

Boris Yeltsin with the Russian flag during the August Coup, 1991.

The failed coup erased what had remained of the Communist Party’s credibility, and people now sought not to reform the Soviet system but to terminate it. In the ensuing months, the fifteen national republics that made up the Soviet Union declared their independence and became separate countries.

On December 25, 1991, Gorbachev resigned as the leader of a Soviet Union that no longer existed. The Soviet flag with its hammer and sickle came down. The Russian tricolor was raised above the Kremlin in its place.

The breakup of the Soviet Union clearly reflected a lack of ideological commitment among the population. But popular disillusionment with Communism does not entirely explain the downfall of the Soviet system. Party officials, government functionaries, and industrial managers all enjoyed considerable power and privileges under Soviet rule.

Why didn’t these elites fight to defend the system?

The answer to this question helps explain not only the fall of Communism but also what happened next. Many elites realized that they could benefit from a cashiering of the old system.

This map of the former Soviet Union shows when countries broke away to form their own republics.

Previously, leaders of the Soviet republics had to take orders from the Kremlin, but now they became heads of state. Yeltsin, formerly leader of the Russian republic, became President of the Russian Federation. Leonid Kravchuk, no longer chair of the Ukrainian republic’s parliament, became Ukrainian President. Representatives in the largely symbolic parliaments of each Soviet republic now gained real legislative power.

A similar shift occurred in the economic sphere. With the transition to capitalism and private ownership, managers who had run Soviet factories became the owners of those factories. Government officials who had overseen Soviet petroleum production acquired oil fields as their own personal property.

Shock Therapy

Eager to sweep aside Soviet structures, Yeltsin eliminated much of the state-run economy and introduced market reforms. This rapid transition to capitalism in Russia (mirrored to varying degrees in other former Soviet republics) caused tremendous economic upheaval. Those able to privatize old state assets into their own hands became rich, while average Russians suffered a sharp drop in living standards.

Facilitating the plunder of state properties was a group of American economic advisors led by Harvard economist Jeffrey Sachs. Yeltsin implemented Sachs’s program of shock therapy—freeing prices and selling off state enterprises—with no regard to the social consequences.

A flea market in the streets of Rostov-on-Don, 1992.

Shock therapy reflected a facile belief that privatization and the free market would produce the best outcome for all. Concerns about legal safeguards and the equitable distribution of resources were shunted aside. A few Russians became fantastically wealthy, while most people lost their life savings in the hyperinflation of 1992.

Russia paid a political as well as an economic price for shock therapy.

In people’s minds, liberal democracy and market reforms became synonymous with hardship, corruption, and economic chaos. Unemployment spiked and crime proliferated. Coupled with Yeltsin’s poor health and erratic (often drunken) behavior, shock therapy discredited liberal reforms. People began to look for a strongman who would restore order and reestablish a dominant central state.

That strongman emerged in the person of Vladimir Putin when Yeltsin resigned his presidency at the end of 1999.

Vladimir Putin with Boris Yeltsin on December 31st, 1999, when Yeltsin announced his resignation.

As the new Russian president, Putin reversed the decentralization of power that had occurred under Yeltsin. He reacquired state control over major economic assets, including Russia’s vast oil and natural gas reserves. He clamped down on crime but also on political dissent. He curtailed freedom of the press, not by prohibiting private media outlets but by gaining state control of all national television networks.

Favorable television coverage has guaranteed Putin and his political party, United Russia, repeated victories in presidential and parliamentary elections. While Russia still holds contested elections, then, its political system is not truly democratic. Political scientists have categorized Russia as an authoritarian government or illiberal democracy, where the results of elections are predetermined and where freedom of the press and of assembly do not exist.

The United States also paid a price for pushing Russia’s rapid transition to neo-liberal capitalism with no regard for legal safeguards or the population’s wellbeing.

Immediately following the Soviet collapse, Russian public opinion viewed the United States highly favorably, seeing it as a friend and ally. Thirty years later, most Russians regard the United States as an antagonist—a foe that deliberately weakened their country through the introduction of foreign economic models.

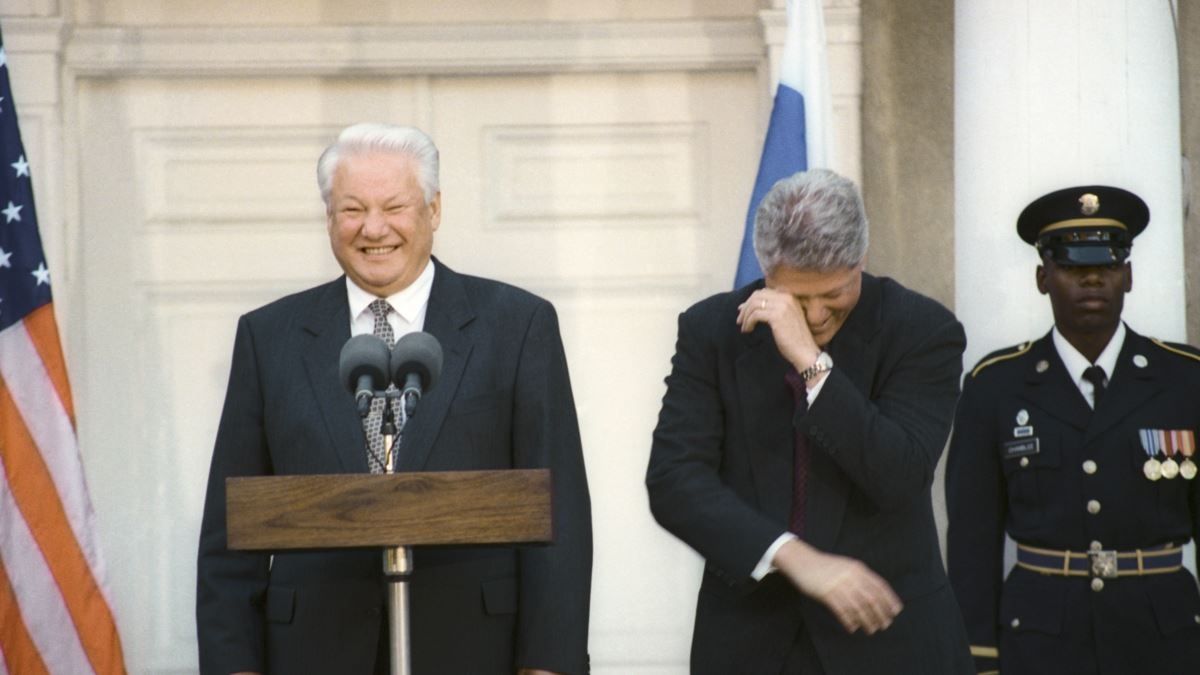

U.S. President Bill Clinton and Russian President Boris Yeltsin at the White House, 1995.

They also resent the fact that the United States took advantage of Russian weakness in foreign policy. In 1999 and again in 2004, the United States approved the expansion of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) to incorporate East European countries and even the former Soviet republics of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania.

Russians saw NATO expansion as the enlargement of a hostile military alliance right up to their border. And it was the prospect of Ukraine joining NATO that prompted Putin to intervene in eastern Ukraine and seize Crimea in 2014. While the American media often demonizes Putin as the cause of Russian-American discord, most Russians applaud him for standing up to the United States and defending Russia’s international interests.

The End of History?

The collapse of the Soviet Union was the world’s most momentous event of the late twentieth century.

Soviet and American tanks face each other at Checkpoint Charlie during the Berlin Crisis, 1961.

The Cold War—the rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union that had dominated international politics for forty years—came to an end. Even more unexpectedly, one of the world’s two superpowers also came to an end. Since the October Revolution of 1917, Soviet Communism had posed an enormous ideological challenge to liberal democracy and industrial capitalism. In 1991, that challenge dissolved.

In a wave of post-Cold War triumphalism, one American commentator labelled the Soviet collapse the “end of history,” seeing the liberal democratic order as victorious and predicting that it would face no ideological challenges in the future. The collapse of the Soviet Union was indeed a momentous event in world history.

Three decades later, however, it is clear that history did not come to an end. On the contrary, ideological conflicts still rage across the globe. The liberal democratic order today faces challenges from both within and without—the Russian authoritarian model of illiberal democracy being just one of those challenges.

If there is a conclusion to be drawn from the Soviet collapse, it is one connected to the meaning of the Soviet project itself. Commentators today sometimes dismiss the entire Soviet period as a heinous misadventure—a 74-year historical wrong turn inflicted upon the country by Communist thugs.

Lenin, Trotsky, and Kamenev celebrating the second anniversary of the October Revolution, 1919.

This view ignores the fact that Communist revolutionaries held genuine ideals. They sought to create a better world—a society free of exploitation and class antagonism.

For them, the October Revolution represented the dawn of a new epoch, where workers of the world would unite rather than killing one another, as had happened in the senseless slaughter of World War I. Soviet leaders in fact established a non-capitalist system and modernized their country remarkably quickly. But to do so they used massive coercion and state violence, incarcerating and executing millions of people.

Looking back, it is clear that the means they employed were in contradiction with their ends—state violence did not produce social harmony, and the utopia they promised was never attained. Eventually this state violence also contributed to the downfall of the Soviet Union.

When Gorbachev lifted censorship in the late 1980s, discussion of the system’s violent past quickly undercut its legitimacy. Along with economic discontents and nationalist separatism, this legacy of state violence eroded support for the Soviet system and hastened its demise.

More broadly the Soviet experiment raised doubts among social thinkers about the role of the state in reshaping society. In the post-Soviet world, people are far less likely to embrace grand plans for state-directed social transformation. Thirty years after the Soviet collapse, we can see that it did not signal the end of history, but it did mark the end of an era.

Archie Brown, The Gorbachev Factor

Timothy Colton, Yeltsin: A Life

Robert V. Daniels, ed., Soviet Communism from Reform to Collapse

Karen Dawisha, Putin’s Kleptocracy: Who Owns Russia?

Stephen Kotkin, Armageddon Averted: The Soviet Collapse, 1970-2000

David Remnick, Lenin’s Tomb: The Last Days of the Soviet Empire

Steven Solnick, Stealing the State: Control and Collapse in Soviet Institutions