We are living through the Fourth Industrial Revolution, characterized by artificial intelligence, automation, interconnectivity, and genetic manipulation. These new technologies open all sorts of opportunities for humans, but also are changing the lives of workers and consumers in profound and often disturbing ways. Of course, this is not the first time that humans have experienced economic disruption through industrial change. This month, historian Matthew Smith introduces us to Ned Ludd, and the so-called Luddites, from the First Industrial Revolution. He explores how Ludd spoke to issues of work, community, and technology in ways that have remained relevant through each successive stage of technological change down to today.

Today we are living through the Fourth Industrial Revolution, as Klaus Schwab argues, thanks to such innovations as 5G wireless, 3D printing, genetic editing, smart sensors, self-driving vehicles, and the Internet of Things. Yet these new technologies and the workplace automation they bring threaten to cause large-scale unemployment and deeper economic inequality.

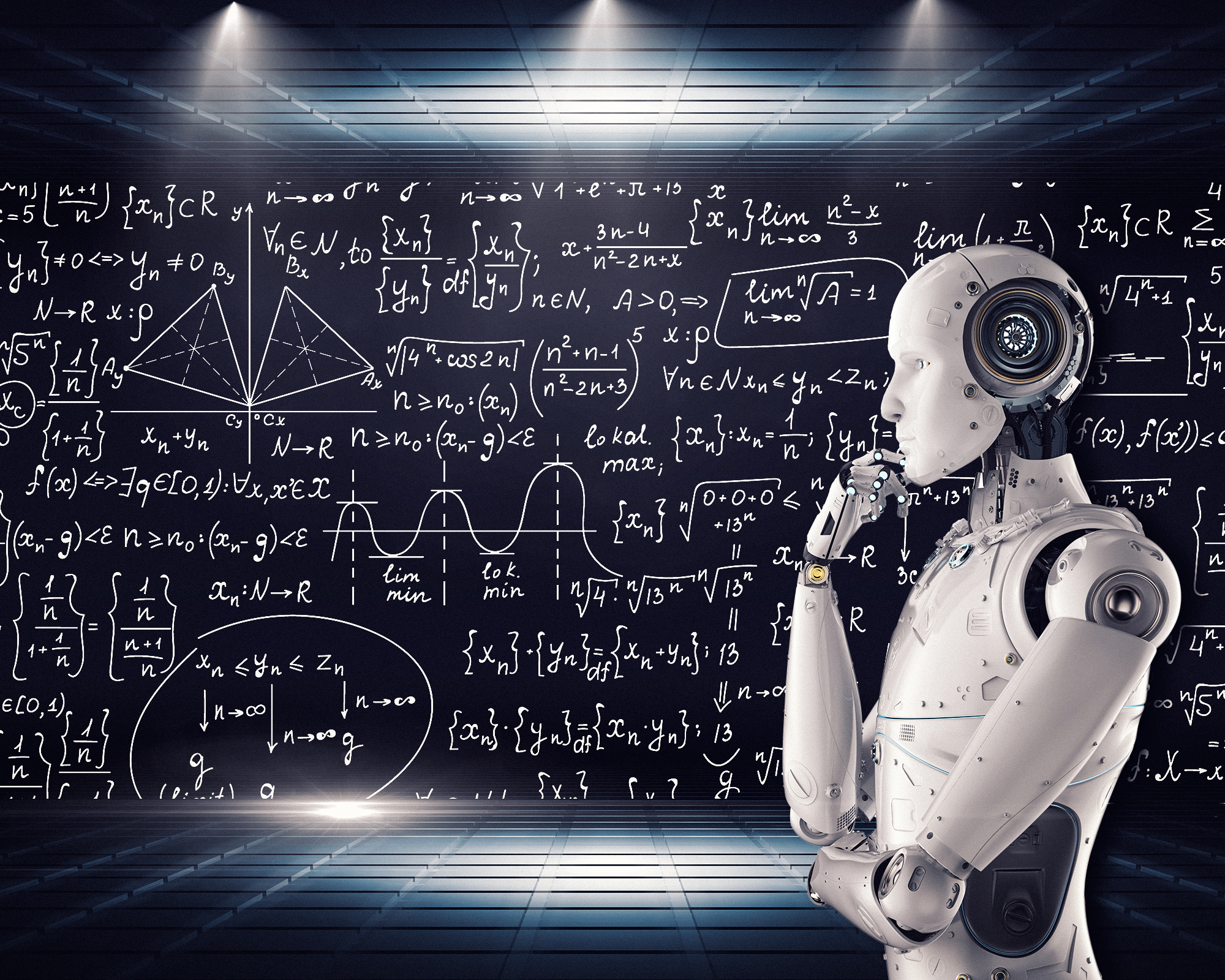

An artist's depiction of artificial intelligence featuring a humanoid robot learning.

The merger of biology and technology, of human consciousness and artificial intelligence, entailed by these innovations recalls the axiom attributed to Arthur C. Clarke: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” Whether the magical technology of the Fourth Industrial Revolution turns out to be a boon or bane to humanity remains to be seen.

But one thing is certain: now is not the first time that humans have experienced economic disruption during periods of rapid technological change, altering the lives of workers and consumers of the world and causing backlash.

In a 2015 Foreign Affairs article, Schwab outlines the previous three industrial revolutions: mechanized production by steam power in the first, mass production by electricity in the second, and automated production by digital information in the third. The current revolution is “characterized by a fusion of technologies that is blurring the lines between the physical, digital, and biological spheres.”

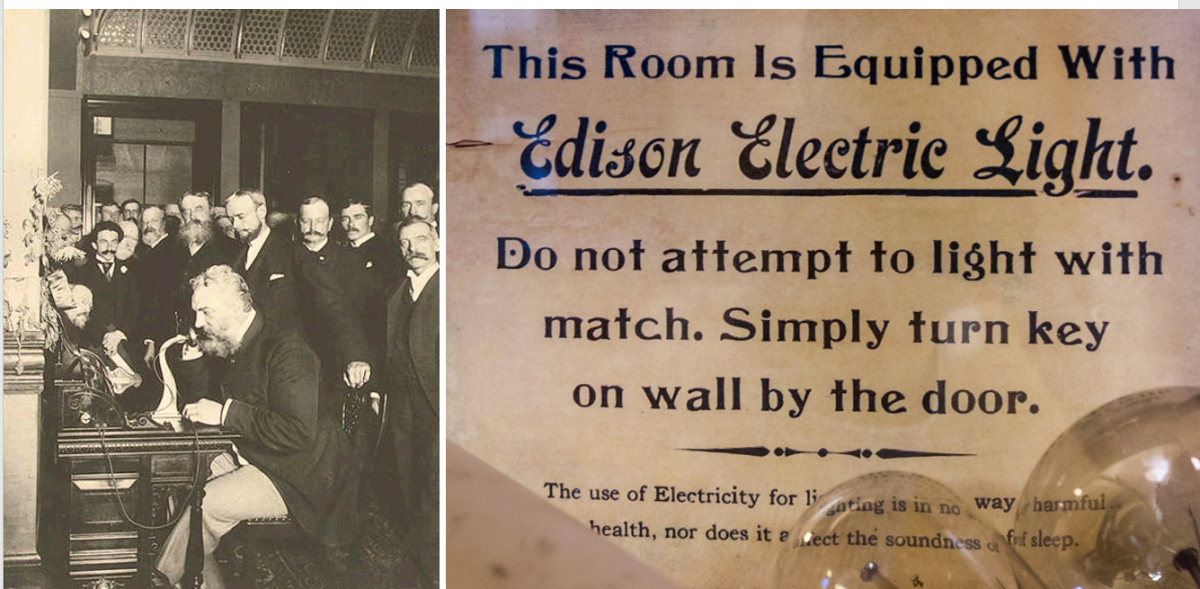

More specifically, the harnessing of fossil fuels, the growth of the factory system, and mechanization characterized the First Industrial Revolution in eighteenth-century Britain. Electrification and telecommunications, led by nineteenth-century American innovators such as Morse, Bell, Tesla, and Edison, shaped the Second.

Alexander Graham Bell at the opening of the long-distance line from New York City to Chicago, 1892 (left). A sign with instructions on the use of Edison Electric Light from the late nineteenth or early twentieth century (right).

The global rise of microcomputing brought about the Third Industrial Revolution after World War Two. Next-generation smart technology, Big Data, and automation herald the latest revolutionary cycle, defining the transnational twenty-first century.

Although the heralds of the Fourth Industrial Revolution promise efficiency, economic growth, and global connectivity, these changes also hold sinister potential for the workers whose lives are changed by new technologies.

One commercial advertisement for Lumen, “The Platform for Amazing Things,” for example, promises “adaptive networking, edge cloud, connected security, and collaboration,” among other wonders of its business technology suite. Such products might appeal to corporate CEOs. But rational innovation from one perspective often demands disruptive innovation from another.

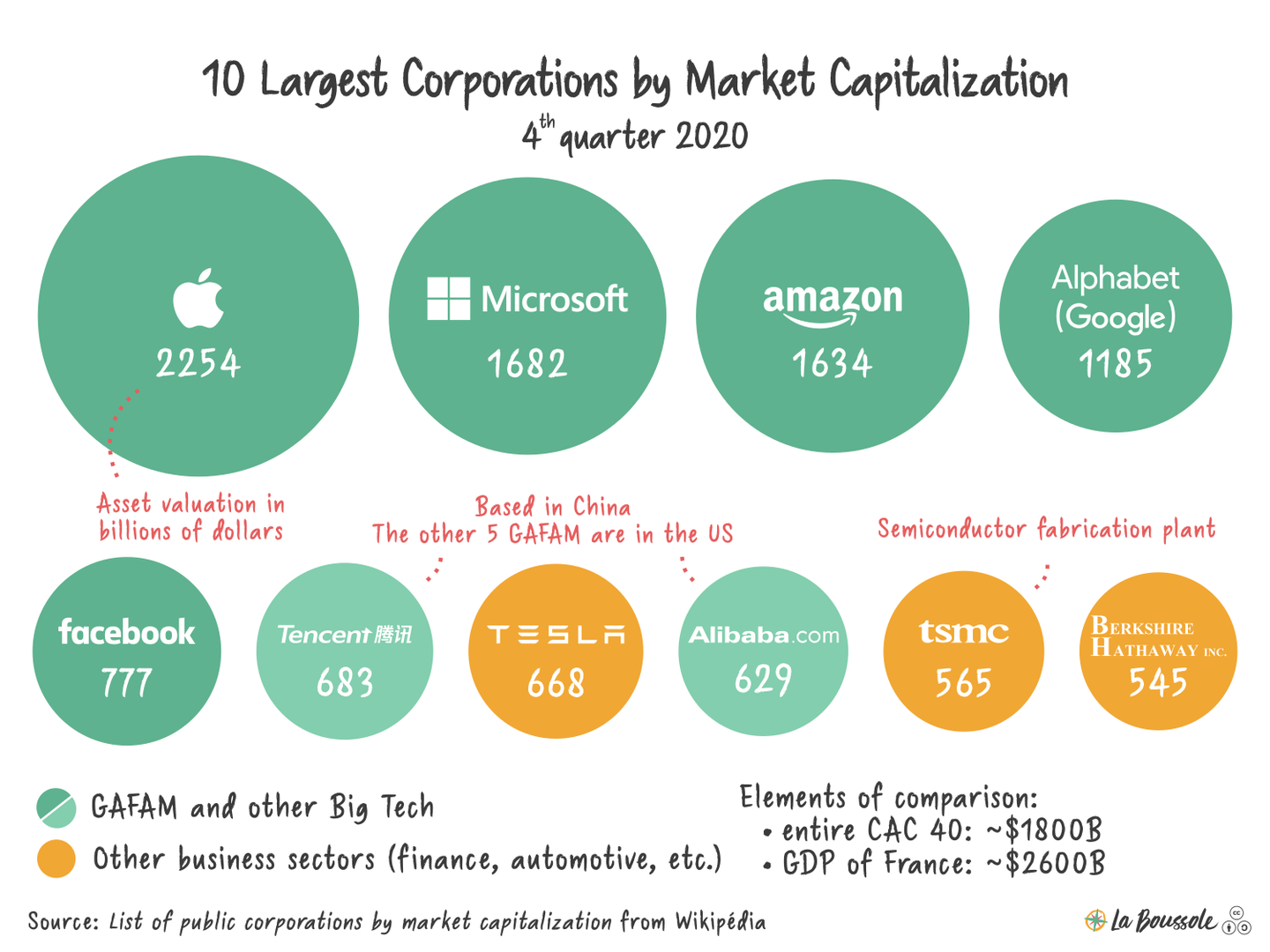

What do the sort of labor-saving (or labor-eliminating) innovations peddled by Lumen and other Big Tech companies mean for ordinary consumers and workers? Who, or what, drives technological change in the twenty-first century? How can technology’s deleterious effects on work and labor be resisted, or at least mitigated?

To help answer these pressing contemporary questions, let’s travel back to late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth-century Britain and meet a man named Ned Ludd.

You might remember him as the legendary machine-breaking saboteur who was once the scourge of industrial capitalism. He has since been reduced in our imaginations to a hammer-swinging emblem of kneejerk reaction against any technological change (to the point that techno-skeptics jokingly adopt the term “Luddite” to describe themselves).

To be a Luddite is to be hopelessly out of step with the modern world. At best it implies a laughable ineptitude with technology—“You’re still on mute!” At worst, it points to stubborn, unthinking opposition to change and innovation in every shape.

Engraving of Ned Ludd from 1812.

Even historians—who should know better—often use the term Luddite to refer to machine-breakers in general, divesting Luddism of its particular historical meaning. Without context, the striking parallels and continuities between the original Industrial Revolution and our own times are obscured.

The Luddites challenged the emerging capitalist system—which centered on efficiency, maximal productivity, and ultimately human redundancy—and instead championed other human values of finely-honed craft skill, community, worker solidarity, and a living wage. If we eschew the violence of Luddism, it is still possible for today’s skeptics of innovation to reclaim the values of the Luddites and the lessons they offer us.

Who Were the Luddites?

A brotherhood of oath-taking saboteurs, the Luddites coalesced under “General” Ned Ludd, in whose name they menaced the mill owners and factory builders of nineteenth-century England.

They were skilled technologists who cared deeply about the toll that mechanization placed on humanity. Contrary to stereotype, they were neither mindless, machine-breaking antagonists of technological progress, nor were they its hapless victims.

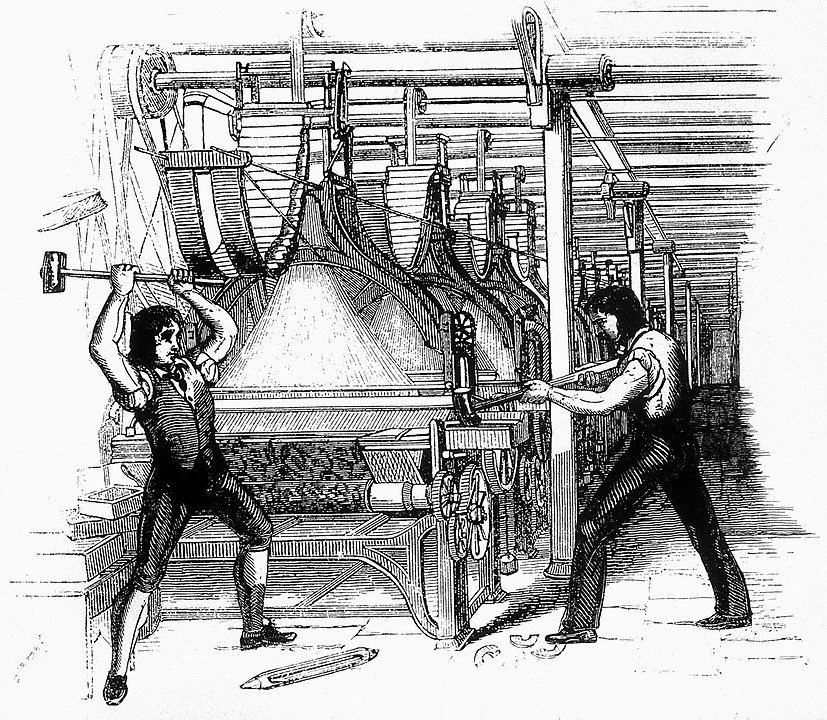

An 1844 depiction of Luddites, or frame-breakers, smashing a loom in 1812.

In addition to demanding higher wages, they opposed disruptive new technologies such as shearing frames and mechanical looms, which threatened their traditional craftways and reduced their skilled labor to servile dependence on machines.

They opposed the policies that paved the way for the Corn Laws of 1815. This hated legislation fixed the domestic agricultural market against cheap imported grain and inspired further radical agitation, including outbreaks of agrarian machine-wrecking.

Luddism amounted to far more than indiscriminate vandalism and rage, but any discussion of Ludd and his associates must confront its violent tendencies—which went beyond destruction of property.

One May 1812 letter sent to an English mill owner from “E. Lud,” for example, warned the recipient to raise his workers’ wages or “thee shalt Rue for it the same as Pearcevel” (referring to Prime Minister Spencer Perceval, assassinated in an unrelated incident that same month).

The combination of this violence and fears of sedition during Britain’s war with Napoleon (1803-1815) prompted Parliament to divert thousands of soldiers in a heavy-handed crackdown on Luddite rebellion.

While the Luddites today would be branded domestic terrorists, political violence was then commonplace, sanctioned by swaths of the disenfranchised. The farm laborers who attacked threshing and other agricultural machines of the 1830s rallied under the banner of “Captain Swing,” in what have come to be known as the peasant “Swing Riots” of rural England.

Unlike Captain Swing, however, Ned Ludd was likely a real person. A sort of working-class Robin Hood, Ludd’s biography remains cloudy, but his notoriety was irresistible.

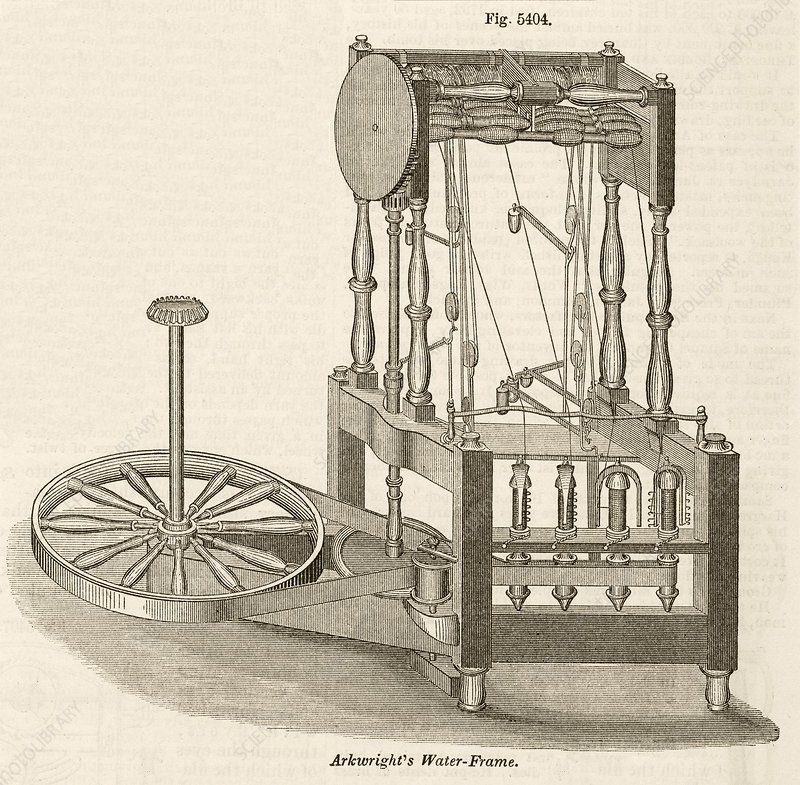

An 1811 article in the Nottingham Review, “The Origin of Ned Ludd,” asserted that he was “not, as many people suppose, an ideal personage,” but an apprentice from Leicestershire who destroyed a mechanical stocking frame with “a great hammer.” Ludd’s alter ego soon rose to its zenith: “Hence the persons who have lately repeated Ned’s operation, on a very extended scale, in this and neighbouring counties, have thought proper to assume his name, and conceal their own.”

Between 1811 and 1817, this insurrection of artisans slowed the tide of mechanization, as Luddites smashed looms, stocking machines, and spinning frames across the country. A song of this period jauntily implored:

Chant no more your old rhymes about bold Robin Hood,

His feats I but little admire

I will sing the Achievements of General Ludd

Now the Hero of Nottinghamshire.

“Collective Bargaining by Riot”

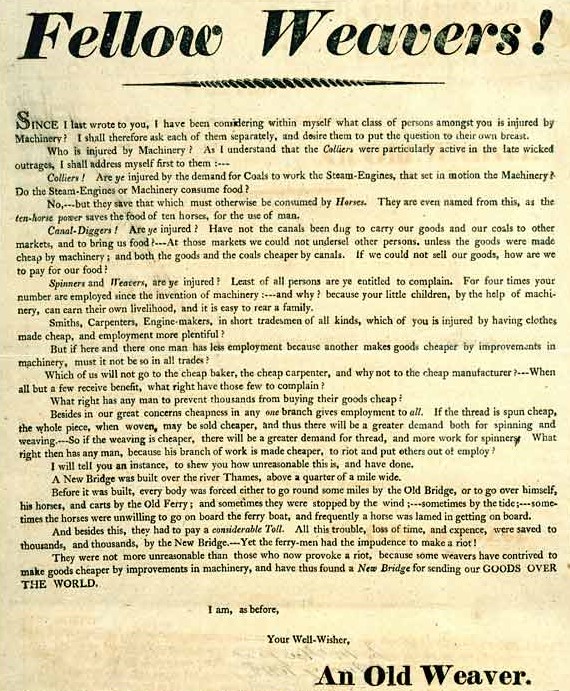

Admittedly, resistance to technological innovation was not unique to the Luddites, nor even to England. Karl Marx, for instance, was among the first modern writers to connect the plight of Luddite craftsmen with the suffering of Indian cotton weavers, whose homespun industry perished under the bootheel of empire.

In Das Kapital, Marx quoted India’s Governor General, who reported in 1835: “The misery hardly finds a parallel in the history of commerce. The bones of the cotton-weavers are bleaching the plains of India.”

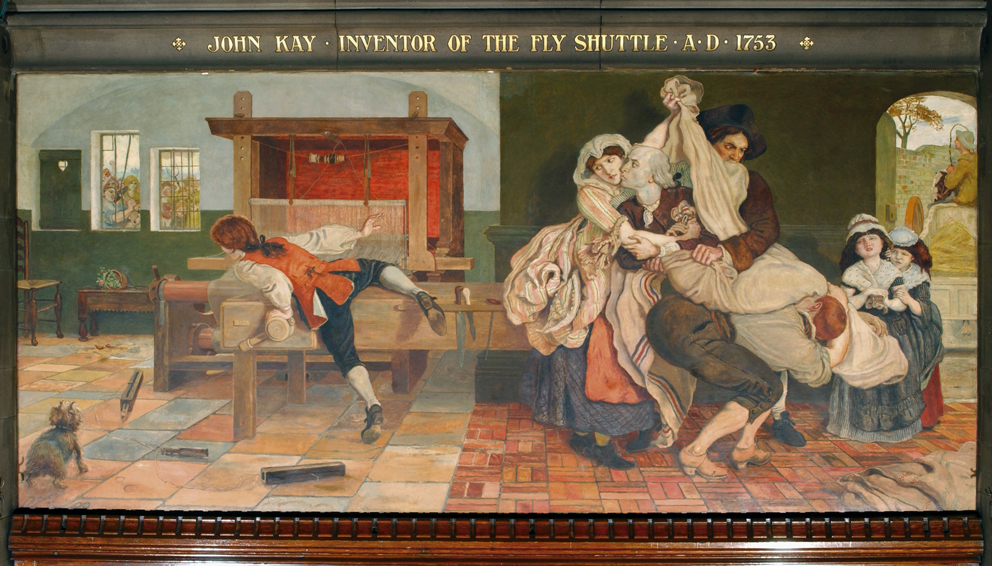

The mural John Kay inventor of the Fly Shuttle AD 1753, by Ford Madox Brown, shows the inventor John Kay kissing his wife good-bye as men carry him away from his home to escape a mob that is angry about his labor-saving mechanical loom.

The dismantling of India’s flourishing artisan textile industry contributed to anti-British resistance, but in Britain itself the problem of mechanization was perennial. As one historian noted, machine-breaking in general became a “serious phenomenon” sometime in the 17th century.

This “collective bargaining by riot” encompassed everything from earlier sabotage by craft workers in the cotton, wool, and silk industries to organized machine-wrecking and arson by Northumbrian coal miners in the 1740s.

In eighteenth-century Britain, it has been claimed, “the typical and ever recurring form of social protest was the riot.” Riots were hardly encouraged by local magistrates, but nor was crowd action equated with revolution.

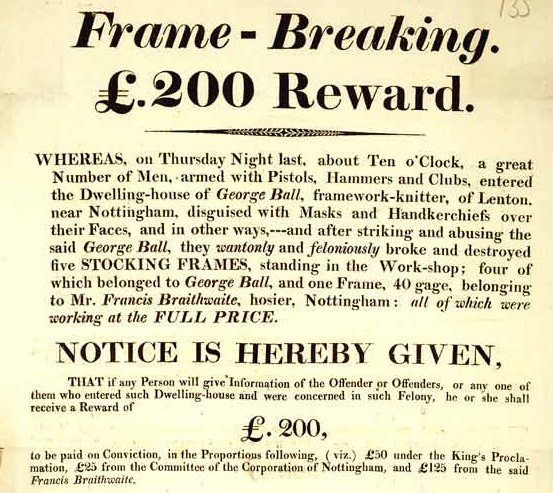

The crackdown of the Luddite era underlined a shift from toleration for “redressing” grievances to more modern, coercive forms of regulation. First, the Combination Acts (1799 and 1800) outlawed unionization, branding organized labor as sedition. The 1812 Frame-Breaking Act made machine-wrecking punishable by death.

Reward poster for frame breakers in Nottingham, 1812. From the National Archives.

Among the few parliamentary voices of dissent, Lord Byron warned: “You may call the people a mob; but do not forget, that a mob too often speaks the sentiments of the people … How will you carry the bill into effect? Can you commit a whole country to their own prisons? Will you erect a gibbet in every field, and hang men up like scarecrows?”

But the Frame-Breaking Act passed with little opposition. In January 1813, less than a year after Byron imagined men hanging like scarecrows, the horror of his vision was realized. Seventeen Luddites were hastily tried and hanged at York Castle in one week (fourteen in a single day), convicted of an assault on a local mill and the murder of a detested woolen manufacturer.

“A Comparative State of Luxury”

Ned Ludd’s “army of redressers” fought on, but in the end, economic humiliation ground them into submission. We might nostalgically recall these artisans for their egalitarian humanity, as much as we lament their subsequent immiseration.

Inequalities existed among the working communities of textile artisans—notably among the master clothiers—but these “small makers” and their journeymen enjoyed much freedom, working their own hours and earning good wages.

One English magistrate called them “so extravagantly paid that by working three or four days a week they could maintain themselves in a comparative state of luxury.” By 1818, when these words were written, such supposed extravagance was a thing of the past, a working-class heyday condemned to obsolescence.

From the perspective of organized labor, Luddism bore fruit. A “habit of solidarity” was planted early, leading to the Anti-Corn Law League and Chartist reform, while encouraging the foundation of trade unionism. Of course, we can easily overstate the ideology of individual Luddites, who ranged from cultivated freethinkers to the plainly illiterate. While Luddism represented “the making of the English working class,” to use the great historian E. P. Thompson’s phrase, its roots were pre-modern, grounded in place, limits, and tradition.

Working-Class Radicalism and Technological Ambivalence

Ned Ludd’s ironic virtue was to have flourished before Karl Marx first drew breath in his home city of Trier, Germany (Marx was born in 1818, the year after the last Luddite uprising). Moreover, Marx raged against capitalism, rather than the machine, calling machinery: “a victory of man over the forces of Nature, but in the hands of capital, [it] makes man the slave of those forces.”

An image of Karl Marx in an edition of Das Kapital.

As Marx’s ambivalence about technology suggests, the Luddite legacy is complex. In the United Kingdom, Luddism presaged popular agitation, but the technological focus of such unrest diminished as industrialization tightened its grip.

Insurrection persisted in rural England, where the impact of mechanization was most keenly felt, and attempts at unionization were ruthlessly suppressed. The Tolpuddle Martyrs, a group of agrarian organizers banished to Australia in 1834, symbolized the draconian policies of the era.

At the same time, working-class radicalism parlayed enthusiasm into political reform, encouraging the Parliamentary Reform Acts of 1832 and 1867, which broadened the vote.

In Britain and elsewhere in the industrialized world, inclusion of working-class voters in the political system eased the agonies of industrialization while forestalling actual political revolution, such as befell Russia in 1917. Invariably, political reform was coupled with the growth of public education, which provided some social mobility while acculturating children to the demands of technological society.

The Second Industrial Revolution

In the United States, where the Second Industrial Revolution took hold, circumstances differed radically from those in nineteenth century England, even if the challenges of mechanization were comparable.

The transformation of American society by immigration, the relative absence of entrenched craftways, the intensity of racial and ethnic animosities, and unprecedented geographic mobility conspired against the formation of the same sort of class consciousness that England had seen.

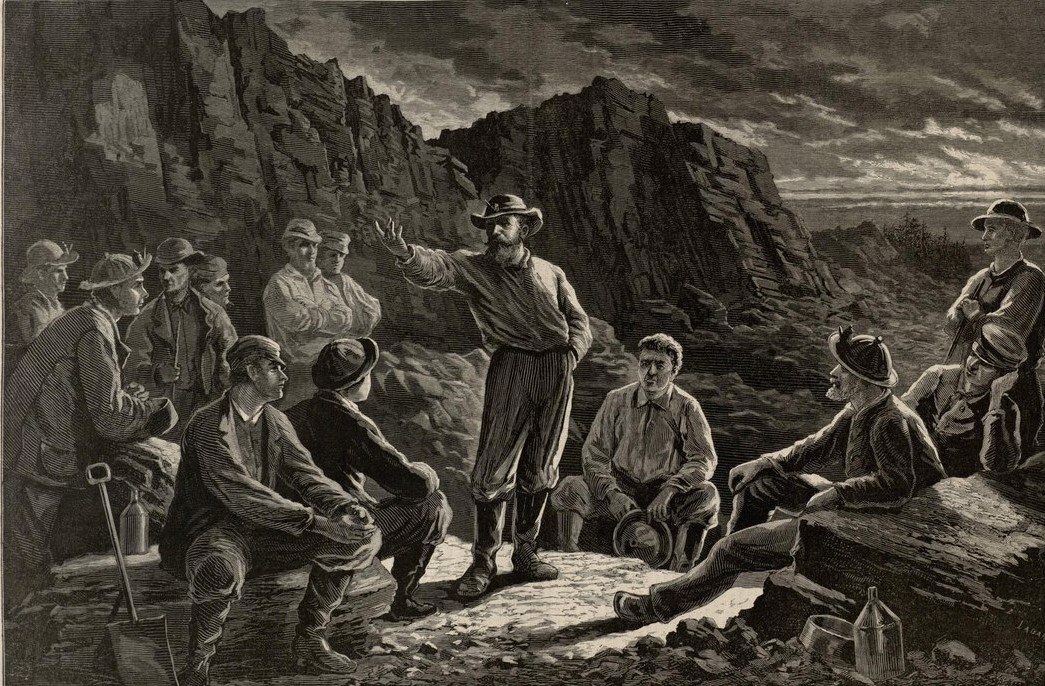

An illustration of the Molly Maguires from Harper's Weekly, January 31, 1874.

Numerous superficial analogies to Luddism can, admittedly, be found within the history of American labor. Perhaps the most striking comparison is the Molly Maguires, the shadowy band of Irish Americans who fomented insurrection in the anthracite coal fields of Pennsylvania in the 1870s.

But the parallels wear thin. True, the Molly Maguires engaged in acts of violence and sabotage, but these actions lacked the critique of technology and concern for craftways that defined Luddism.

The Molly Maguires sprang from nationalist societies such as the Ribbonmen formed during the Great Famine of 1840s Ireland, bearing their militancy with them to the New World. Such ethnocentric radicalism explains the limited scope of the Molly Maguires and similar militant groups in subsequent American history.

From the Memex System to Ted Kaczynski

A few short generations after the heyday of steam power, the era of the computer heralded the Third Industrial Revolution in the shadow of Hiroshima.

Boeing B-29 Superfortress bombers under construction on an assembly line, 1944.

The Cold War military-industrial complex fostered a growing interdependence between the knowledge economy and labor, not to mention technological progress and scientific education. During the First Industrial Revolution in England, gifted amateurs like Thomas Newcomen and Matthew Boulton—ingenious tinkerers rather than professional technologists—frequently drove innovation.

During the Third Industrial Revolution, by contrast, private capital and government funding created the modern American research university, which inculcated research and development as both a means to an end and a worldview in itself.

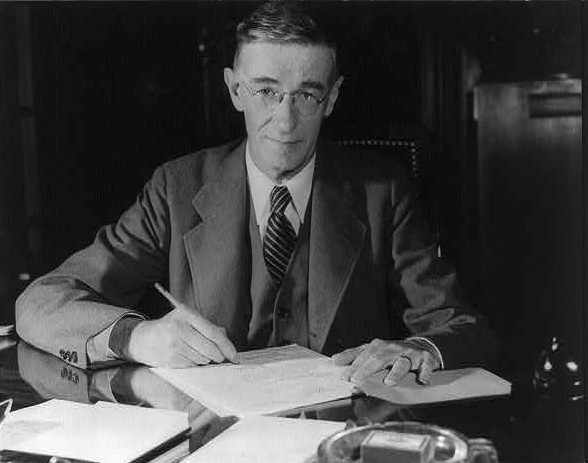

As early as 1945, MIT professor Vannevar Bush heralded the limitless potential of electromechanical technology to extend human capacity, forging a knowledge revolution from the exponential growth of information.

Vannevar Bush in the early 1940s.

His hypothetical Memex system was “a device in which an individual stores all his books, records, and communications, and which is mechanized so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility. It is an enlarged supplement to his memory.”

Though Bush’s Memex quaintly anticipated the World Wide Web, the information superhighway has blazed a troubling legacy. Not only has it extended the reach of our minds, but it has increasingly reconstituted the nature of intellectual labor itself.

Unfortunately, the solitary individual most representative of technological resistance during this period, at least in American popular memory, is Ted Kaczynski. A Math PhD trained in complex data analysis, Kaczynski—also known as the Unabomber—revolted against the technological-scientific worldview into which he was educated.

Ted Kaczynski during his time as an assistant professor at UC Berkeley, 1968.

His one-man reign of terror against technology and technologists invites comparison with the violent excesses of Luddism, but unlike the Luddites who found solidarity in resistance to mechanization, Kaczynski’s murderous rage derived from his peculiarly misanthropic paranoia.

His personal manifesto Industrial Society and its Future (1995) contained no mention of the Luddites or their legacy, instead critiquing the alleged “feelings of inferiority” and “oversocialization” that underwrote contemporary social decline. Such animosity may have stemmed from a series of brutalizing psychological experiments to which Kaczynski subjected himself as a Harvard undergraduate, purportedly as part of CIA-backed mind control research.

Ironically, the French theologian, sociologist, and historian Jacques Ellul, who most shaped Kaczynski’s philosophical worldview, was a committed Christian pacifist.

Ellul’s influential work, The Technological Society (1954), critiqued the rampant development of “technique” (the French term including forms of knowledge and social organization broader than the English word “technology”). Ellul’s concern for maintaining technology within human purpose and control is something, at least, Kaczynski and Ned Ludd would have agreed upon.

Technology and its Discontents Today

Following the Third Industrial Revolution, we at last return to the present and Fourth industrial Revolution. Today’s technological innovations and their application to the workplace—analogous to mechanization in the First Industrial Revolution—threaten to push many people out of jobs and to shift the locations and opportunities for work.

Projections of economic disruption vary widely, but scholars agree that most occupations will change, as automation transforms not only physical but also cognitive labor. Even if mass unemployment is averted, automation promises various forms of misery as workers are uprooted.

As one think tank noted, the burden will fall on policymakers to “evolve and innovate policies that help workers and institutions adapt to the impact of employment.” Policy demands “will likely include rethinking education and training, income support and safety nets, as well as transition support for those dislocated.”

And it is probably too late to turn around the ship, where such disruption is concerned.

Industrial robots are used at a bakery for automated food production.

Since 2000, U.S. labor wages and benefits fell over 3.5 percent as a share of national wealth. The IMF attributes 47-57 percent of this unprecedented, continuing decline to automation. Another recent study predicted that fully half of all American jobs may be fully automated within the next generation.

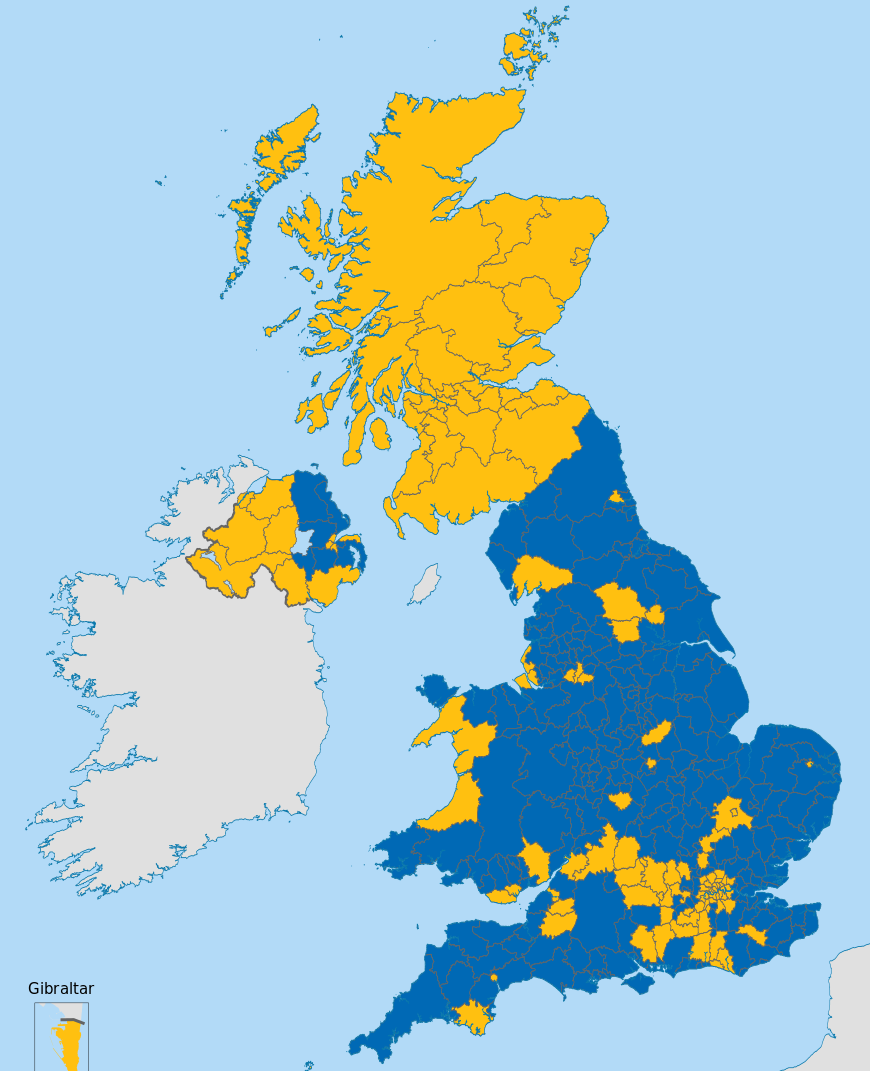

On the verge of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, the economic costs of technological progress remain painfully apparent, often ironically so. Surely it is no coincidence that English counties such as Yorkshire, Lancashire, and Nottinghamshire that comprised the Luddite heartlands overwhelmingly voted to leave the technocratic European Union in 2016.

A consumer survey that year, by the polling organization YouGov, revealed the top ten favored brands of pro-Brexit Leave voters versus pro-European Remainers. Brexiteers preferred “traditional, straightforward, simple, down-to-earth, good value and friendly” brands such as HP Sauce, PG Tips tea, and Richmond Sausages. Remainers preferred “progressive, up-to-date, visionary, innovative, socially responsible, intelligent” goods and services, such as Spotify, Airbnb, and Instagram.

Though Brexiteers are stereotypically dismissed as provincial, reactionary, and xenophobic, the YouGov poll powerfully suggests how the Brexit vote divided along lines of class as much as ideology, embodied in the materiality (or immateriality) of everyday life.

Traditionally Labour-voting, the Euro-skeptic regions of the English North were also those most neglected economically, from the time of the Luddites to the era of Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s.

In this context, it is no surprise that Arthur Scargill, the militant Yorkshire-born leader of the National Union of Mineworkers was dismissed as a “pithead Luddite” during the Miners’ Strike of the Thatcher years. Scargill was no techno-critic, but the pejorative association stuck easily in the minds of his opponents.

The Ghosts, and Lessons, of Ned Ludd

Though Luddite efforts to stanch the tide of mechanization became the stuff of ridicule, in their failure lessons abound. The Luddites challenged an emerging capitalist system centered on efficiency—a word now synonymous with human redundancy—in favor of craft, labor, and solidarity.

The front pages of Der Spiegel, a German news magazine, reveal fears of automation tracing back to the 1960s. (Image by Petra Wessman)

Fetishization of technological progress obscures the violent, uneven path of its development. It is a dangerous form of historical amnesia rendered more perilous by its convenience. As one technology critic recently wrote: “Automation severs ends from means. It makes getting what we want easier, but it distances us from the work of knowing.” But this work of knowing is always worthwhile, and often necessary.

History provides no easy answers to the challenges of automation, but we might yet derive a flicker of determination from Ned Ludd and his aspirations for a different form of production and more humane relationship to technology and machines.

Nicholas Carr, The Glass Cage: Automation and Us (New York: W.W. Norton, 2014).

Arthur C. Clarke, “Hazards of Prophecy: The Failure of Imagination,” Profiles of the Future: An Inquiry into the Limits of the Possible (London: Pan Books, 1973).

Jacques Ellul, The Technological Society (London: Vintage Books, 1966).

E.J. Hobsbawm, “The Machine Breakers,” Past & Present, no. 1 (February 1952).

Kevin Kenny, Making Sense of the Molly Maguires (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Thomas Malthus, Observations on the Effects of the Corn Laws, and of a Rise or Fall in the Price of Corn, on the Agriculture and General Wealth of the Country (London: John Murray, 1815).

Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, trans. Samuel Moore and Edward Aveling (New York: International Publishers, 1967).

Mega Mohan and Ed Main, “Do Your Favorite Brands Show How Divided Brexit Britain Is?” BBC News Online (August 2016):https://www.bbc.com/news/blogs-trending-36970535

George Rudé, The Crowd in History: A Study of Popular Disturbances in France and England, 1730-1848 (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1966).

Klaus Schwab, “The Fourth Industrial Revolution: What it Means and How to Respond,” Foreign Affairs (December 2015).

Malcolm Thomis, The Luddites: Machine-Breaking in Regency England (Hamden, Connecticut: Archon Books, 1970).

E.P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class (New York: Vintage Books, 1966).