In launching a full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, Vladimir Putin has repeatedly invoked the memory of World War II to justify his actions and to rally support from the Russian people. In fact, WWII casts a long shadow all across the globe and over the next several months Origins will publish essays that explore the memory of the war in different parts of the world. This month historian Maria Bucur looks at the meaning of the war in Eastern Europe.

In the aftermath of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the countries formerly designated as the “East European communist bloc” displayed a remarkable solidarity in support of Ukraine. Officials from Estonia echoed those from Romania, Slovakia and other states in condemning the invasion.

While Putin has justified his brutal war as “liberating” Ukraine from neo-Nazis, government officials in many East European countries see the analogy in exactly the opposite way. For them, Putin’s actions recall the German invasion of Eastern Europe before and after the Hitler-Stalin Pact of 1939.

More poignantly for many non-Russians who lived in or next to the Soviet Union for half a century or more, this war looked like the “liberation” suffered by Estonians, Lithuanians, Latvians, Poles, Czechs, Slovaks, Hungarians, Romanians, Bulgarians, Serbs, Croats, Slovenes, Montenegrins, Bosniaks, and Albanians starting in 1944 when Soviet troops moved into those areas and stayed until the USSR itself collapsed.

Nevertheless, experiences of World War II as well as the memories of those who survived its brutality and chaos are diverse and even divergent across this region. These differences presently shape how East European governments and citizens understand their relationship to Europe, their citizenship rights, and their claims to specific cultural symbols.

Creating Eastern Europe After World War I

To begin with, most of these states acquired territories and populations after World War I, some because of the dissolution of the Russian Empire and therefore at the expense of the newly established Bolshevik regime in Moscow.

A few states (especially Hungary and Bulgaria) lost territories and population, rendering them proponents of revisiting the postwar treaties. There was little trust between Hungarians and Slovaks or between Bulgarians and Romanians during this period.

Small groups across Eastern Europe cheered the Bolshevik Revolution and fought for similar transformations, most prominently in Hungary and Germany. Yet communist parties in most East European countries were banned during the 1920s.

The resurgent nationalism of that era also played out differently in different countries after the war.

Some regimes, most prominently Czechoslovakia, went out of their way to acculturate ethnic minorities to new forms of citizenship in ways that honored diversity. Others, like Romania, strove to homogenize the diversity of their peoples. They imposed a national unitary state, fantasizing that such a lived reality did not discriminate against minorities.

By the mid-1930s, when Hitler’s rule had been established in Germany, the consequences of racialization of nationalist politics had crystallized for everyone in Eastern Europe.

Responses varied greatly, though overall polarization between “us” (the population meant to receive all the benefits of full citizenship) and “them” (those whose rights would be chipped away on the basis of ethnicity, race, and/or religion) was a general trend in Eastern Europe.

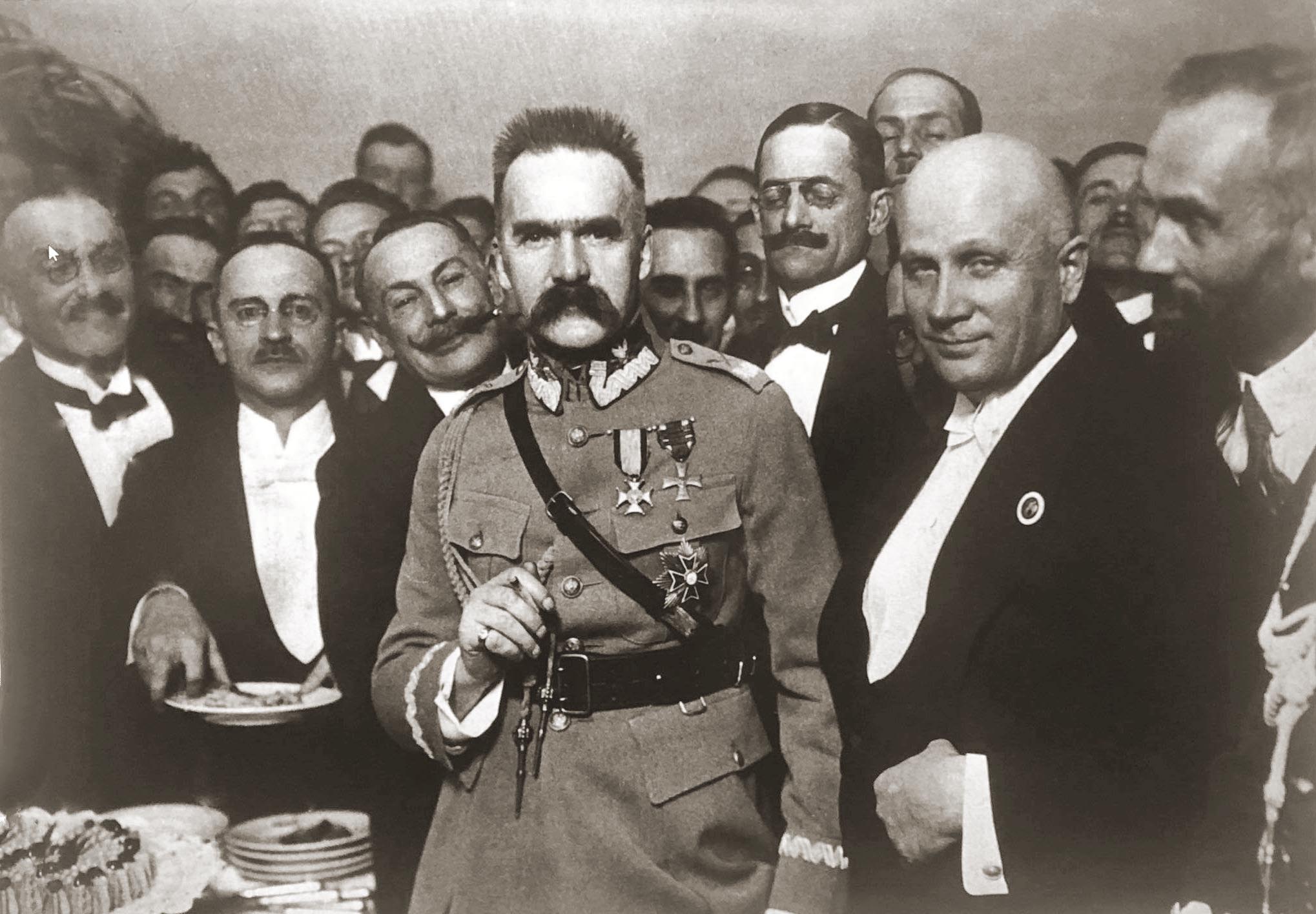

In Poland, for example, the death of Józef Piłsudski opened a space for expressing more aggressive forms of nationalism among the ethnic Polish, Catholic majority, the ethnic German minority, and the Ukrainian nationalist movement in the country’s eastern region. It also created the space for more anti-Semitism, an important development given the size of Poland’s Jewish population.

Zionism also flourished after World War I, polarizing yet other ethno-religious groups.

Similar dynamics among the Czech and Slovak ethnic groups and the German, Hungarian, and Roma groups emerged in Czechoslovakia, poisoned by the seeping toxicity of Nazi propaganda next door. This helped feed the fury of some ethnic Germans in the Sudetenland Western region of Czechoslovakia.

In Yugoslavia, the dream of brotherhood among Serbs, Croats, Bosniaks, and Slovenes dissipated into a constant political crisis while the government acted as a loyal supporter of Serbian interests alone.

After the Anschluss and Hitler’s invasion of Czechoslovakia, the quest for revisiting the postwar borders became a reality that placed all countries of Eastern Europe on notice. In the end, making alliances with Hitler to avoid further harm to their territorial interests worked very differently for Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria.

Hungary managed to retrieve territory lost to Romania, while Romania got the raw end of the deal—losses to both purported allies and to the Soviet Union.

Bulgaria struggled to regain some of its lost territories in Dobrogea. Poland and Yugoslavia were occupied and dismembered like Czechoslovakia, and Greece ended up semi-occupied, though with fewer Nazi boots on the ground.

The level of collaboration with and resistance to Nazi occupiers among civilians under wartime occupation also varied a great deal. Historians are still uncovering the extent of “violence as generative force,” to quote a recent analysis of interethnic slaughter in wartime Yugoslavia.

Even as many declared themselves victims of occupation, some ethnic groups participated in genocidal violence. In areas formally controlled by the Nazis, neighbors slaughtered and burned alive neighbors, especially Jewish and Roma co-citizens.

Poles, Ukrainians, Romanians, Hungarians, Croats, Bosniaks, and Serbs engaged in such attacks repeatedly, often using the Nazi occupation as cover for their own brutality and inhumanity.

Amnesia, Soviet Style

The official memory of World War II in the Eastern bloc was dominated for 45 years by a basic requirement of bowing before the USSR, even as parades and accompanying events grew increasingly nationalist, especially after the death of Stalin.

The heroes being celebrated were always those who had wrested the country—Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Romania, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria—from Hitler’s control.

Heroism (against the Nazis) and victimization (by the Nazis) were entwined. At the victory celebrations, the Soviets were always present at the tribune and on huge placards, portrayed as the protectors and liberators who paved the way for the heroism of the national leaders.

However, Yugoslavia broke away from this script early on, after 1948, and asserted its independence from Stalin’s tight embrace. Joseph Broz Tito became and remained, until his death in 1980, the symbol of a newly revamped nation of “brotherhood and unity” among Yugoslavia’s ethnic communities and the Yugoslav memory of World War II was recast in this way.

Needless to say, the Soviet version of the war erased a great deal. Most obviously, atrocities, especially rape, committed by the Red Army and their local allies in East European countries, were not discussed. Such violence was, and remains, cloaked in shame and grotesque normalization.

The memories of some forms of resistance became submerged, as they had focused on anti-communist activities, and some were outright fascistic in their values. In Romania, small bands of resistors in the Făgăraș Mountains became the subject of myth making and adulation, even as some spoke in openly anti-Semitic and xenophobic terms about their “crusade.”

In Poland, the underground activities of the Home Army, which had worked with the government in exile against both the Nazis and the Soviets, had to be recast in tones that would not offend the Soviets.

Ironically, paying fealty to the USSR sometimes did the work of the right-wing xenophobic underground. At Auschwitz, the site of some of the greatest racist atrocities of the war, the memorialization of the victims erased the racial aspect of these horrors.

Until 1990, the official memorial plaque was titled the “International Monument to Victims of Fascism,” both misstating the number of victims and also identifying Poles, rather than Jews, as the first among the victimized. While Jews came to pray for their lost families and communities, others could be lulled into thinking that everyone was a victim of the Nazis, and nobody thus a perpetrator except the German occupiers.

Memorials to pogroms against Jewish communities were often placed in Jewish cemeteries that became out of reach for most people. Thus, even as communist leaders would gather annually with small groups among the survivors of the local Jewish communities to commemorate the Holocaust, the role of the local ethnic majorities—both civilians and the law enforcement apparatus—in decimating the Jewish population was never made evident.

There was no accountability for the local perpetrators. History textbooks often omitted the total number of Jewish citizens killed during World War II and the participation of the country’s own military or civilians in atrocities.

Roma communities who had suffered similar forms of genocidal violence by their neighbors found even less openness on the part of communist regimes. I am not aware of any memorials that acknowledged their plight.

On the contrary, in places like Czechoslovakia and Romania, communist authorities undertook their own form of racist violence against these minorities, denying them recognition for any beneficial purposes and marginalizing them from access to full citizenship rights.

But even in the post-Soviet period, full accountability for what happened in many parts of Eastern Europe during the war remains elusive. In 2018 the Polish government enacted a law making it a crime to accuse Poles of contributing in any way to the Holocaust, though historians have amply documented Polish complicity.

Overall, Potemkin-like celebratory parades and ceremonies that commemorate the heroism and sacrifice of each country’s army continue to paint over these painful realities. Amnesia and self-pity anchor the memories of many of these East Europeans.

Remembering the Anti-Soviet Resistance

Starting in the late 1960s, veterans who had fought on the side of the Nazis against the Soviets began to organize informally and to commemorate their participation in the war in their own ways. We still have a very spotty idea of what such commemorations looked like and what sort of discourse about heroism and victimhood presided at such events.

These informal communities sustained themselves underground until 1990, when they became a presence everywhere, with unabashed pride in their actions on the front.

They had waited for 45 years to speak freely, and finally could proclaim openly their heroism in fighting against the Soviets and defending their country, even when that meant killing soldiers and civilians beyond the boundaries of one’s own country. Or decimating Jewish and Roma citizens of their own countries under the guise of “cleansing” the fatherland.

The voices of the Jews who survived the Holocaust were silenced until the late 1960s, and even then were carefully curated to not offend the communist leadership’s own narrative about their heroic deeds during the war.

Those who remained in Eastern Europe developed commemorations and memorials—in stone, word, and storytelling—that remained largely limited to their own cultural spaces. Rarely, if ever, did their neighbors ask or listen to these stories of brutality. The surviving Roma, living on the edge of state socialism and barely tolerated by the new regimes, rarely articulated their memories and pain, even in their own communities.

I grew up in Romania in the 1970s and went to school with both Roma and Jewish kids. We played together. We shared treats. We sang and created music together. I never knew about the way my people (ethnic Romanians and Russians—both of my grandfathers fought in the war) had treated their people. I never felt the shame I later experienced as an adult, when I started to educate myself about these issues, after leaving communist Romania in 1985.

The ignorance of my generation became a strong force against laying bare the violence of World War II and the entitlement with which local ethnic majorities saw fit to treat marginalized groups.

After 1989 it was the anti-communist groups that became lionized regardless (or sometimes because) of their words and deeds against marginalized groups. That phenomenon encompassed both cooptation by local and national government institutions—the military, schools, museums—and grassroots efforts.

Thousands of monuments went up through private subscription to men with openly racist positions and who committed atrocities during the war. It wasn’t until post-communist countries joined the European Union (EU) that legislation was passed to render Holocaust denial illegal as well as honoring war criminals. But some monuments were simply moved from public to private property and thus sheltered under new neoliberal understandings of common good and “rights.”

At the same time, civic engagement by members of minoritized groups that survived the atrocities of World War II became more visible.

Jewish and Roma communities began to demand accountability and compensation for the personal and material losses they suffered during the war. While Jewish communities have proven somewhat successful, especially with the support of the Israeli and U.S. governments, the Roma still await their moment of justice.

Still Forgotten

Submerged overall have remained the experiences of East European women during the war. Some women participated in partisan activities (against both the Nazis and the communists), but they have remained secondary in the memorialization of those groups. When they are acknowledged, their participation is either cast as helping in traditional gendered terms, or as extraordinary.

Feminine heroism in battle is still not fully accepted. Not all female partisan veterans, for instance, have received full recognition and benefits for taking the same risks and doing the same work as their male counterparts. As caretakers of their families and homes, women have been depicted as simply doing their job.

The wartime generation understand themselves to a great extent exactly in that way—nothing exceptional, just doing what needed to be done every day to survive. But the structural precarities and vulnerabilities they experienced deserved further visibility to render legible the constant personal risks these women took.

Finally, the experience of sexual violence during the war remains woefully understudied and under-represented in the memory of World War II.

The shame victims experienced at that time and afterwards, the sense many experienced of not fighting enough, or not being strong enough to resist (without guns or other forceful means) their armed perpetrators, or not thinking more about the danger their husbands experienced on the front, have stifled the voices of these survivors.

Until very recently, few scholars had encouraged these women to speak openly about this type of violence as an important aspect of the war. And for many of these women, opening up about events from a long time ago, towards the end of their lives, doesn’t seem a priority.

Svetlana Alexeievich’s rise to global fame has helped draw attention to The Unwomanly Face of War (1985), but her deep exploration into women’s memories of World War II in the Soviet Union has not been followed by a flood of other such projects in Eastern Europe. We may never fully appreciate what their own memories of the war actually are.

The Future of the Memory of World War II

As the last of the people who lived through World War II pass on, so do their personal memories of trauma, shame, fear, dispossession, or anger.

Those who live on have learned from their parents about these intense and mixed sentiments. Their post-memory is shaped just as much by the shifting political, cultural, and even international contexts. Anti-Russian sentiment has remained a strong bonding element in shaping collective memory in Eastern Europe of World War II, but not everywhere.

If Romanians and Poles continue to express staunchly critical perspectives about the role played by the Soviet Union during and especially at the end of the war, many Serbian politicians and a large part of the public harbor much more positive views of the Russians.

Their remembrance of World War II is no longer shaped by a desire to distance themselves from the Soviet Union, even though it was in Yugoslavia that the communist regime first sought to put emphasis exclusively on the Yugoslavs’ own heroism during the war, obscuring the role of the USSR.

The current geopolitical moment of Russian aggression in Ukraine and European dependency on Russian energy to heat homes over the next winter are further reshaping how younger generations see Russia and how they understand the memory of World War II. For many countries in the region, there is no escape from the economic ties that bind them to Russia, given the heavy investment by Russian oligarchs in these countries.

Even as they toe the EU party line of economic sanctions against Russia, these countries are seeing unemployment rise and costs of energy and other services grow precipitously, while Ukrainian refugees continue to crowd many local welfare services that everyone needs more now.

Though resentful of these problems generated by the Russians, people are starting to settle into the realization that Russia cannot be excised from its prominent role in the region. Poking the Russian bear via vilification of the Soviet role in World War II might be popular for populist nationalist parties on the rise in parts of Eastern Europe. But venting these resentments will not help lower the inflation and keep the heat on in January.

Into the future, I suspect that the anti-communist and anti-Russian interpretations of World War II will become more muted. And that the relevance of public commemorations of World War II will itself diminish in a panoply of more diverse commemorative dates along the year.

Even though ethno-nationalism is on the rise in the region and World War II commemorations serve as a focal point for performing patriotism and victimization at the same time, these themes are losing their resonance with younger generations, for whom even the Cold War is prehistory.

Max Bergholz, Violence as a Generative Force: Identity, Nationalism, and Memory in a Balkan Community (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2016)

Maria Bucur, Heroes and Victims: Remembering War in Twentieth-Century Romania (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009)

Heike Winkel, Matthias Schwartz, and Nina Weller, eds., After Memory: World War II in Contemporary Eastern European Literatures (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2021)

Jonathan Huener, Auschwitz, Poland, and the Politics of Commemoration, 1945–1979 (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2002)

Anton Weiss-Wendt, ed., The Nazi Genocide of the Roma: Reassessment and Commemoration (New York: Berghan: 2015)