In the midst of a presidential election campaign that pits a wealthy Republican businessman against a self-proclaimed warrior for the middle class, Americans are talking a lot these days about class. Many credit the Occupy Wall Street movement with making “class warfare”—which, in its contemporary use, is really about tax policy—a driving issue in 2012. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels’ original idea of class struggle emerged with the creation of a class of factory wage earners during the Industrial Revolution. Now the term is a slander used by conservatives such as Karl Rove to imply its historic connection to socialism. This month, historian Sarah Brady Siff explores the history of the ideas and practices of “class warfare” in American history.

*Update: find an interview with Sarah Siff on our podcast.

Readers may also be interested in these recent Origins articles about current events in the United States: Populism and American Politics, Presidential Elections in Times of Crisis, Why We Aren't ‘Alienated’ Anymore, Detroit and America's Urban Woes, the Mortgage and Housing Crisis, and American Political Redistricting.

Class is back.

Whatever its other accomplishments, the Occupy Wall Street movement that sprouted in New York City in September 2011 focused public attention on the issue of wealth inequality. To the millions of Americans facing unemployment, losing their homes, and racking up student loan debt, the idea of a struggling "99 percent" struck a chord.

U.S. citizens have long fantasized that ours is a classless society with limitless upward mobility. But abruptly, people and politicians have started talking about a class divide. More and more of them detect a serious conflict between the rich and poor in society, as this Pew opinion poll indicates.

Lately, conservatives have invoked the term "class warfare" to talk about President Obama's plans to raise tax rates for wealthy Americans. They frequently use it as an adjective, as in "class-warfare rhetoric" and "class-warfare policy."

There are many ways to envision economic class in America. The term "99 percent" is technically nonsense, as the bottom 99 percent of households in America includes plenty of millionaires.

The Congressional Budget Office offered this analysis of household income shortly after Occupy Wall Street started, showing that "after-tax income for the highest-income households grew more than it did for any other group."

Economists Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez chart income inequality historically, showing the top 1 percent of earners have increased their share of wealth over the past 30 years, largely through increased compensation for the "working rich," such as CEOs.

Billionaire Warren Buffet raised some hackles when he suggested in a New York Times op-ed that taxes on the wealthy are far too low. Obama subsequently introduced the Buffett Rule, a tax plan requiring those with annual incomes over a million dollars to pay a minimum of 30 percent.

Obama responded to criticism of his longstanding plans to close corporate and investment tax loopholes by saying, "This isn't class warfare. It's math." But he has also taken the novel step of embracing the role of "warrior for the middle class." In his 2012 State of the Union address, he said income inequality is "the defining issue of our time."

When Obama makes this argument, he is building on a long tradition. The rhetoric of class tension and income inequality has been a defining discourse in American history for more than a century and a half.

Class Comes to America

The term class warfare is a long-lived popular twist on Marxist jargon.

In 1848, revolutionary socialists Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels famously wrote that "the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggle." When The Communist Manifesto was translated into English in the late 1800s, the original German word klassenkämpfen was interpreted in some editions as class warfare rather than class struggle.

Based on their observations of the effects of the Industrial Revolution on British workers, Marx and Engels theorized that capitalism inevitably created conflict between laborers and capitalists. They saw in England that industrialization increased workers' productivity by dividing and specializing jobs. No longer did a cobbler make a pair of shoes from start to finish; now as a wage worker, he cut one piece of leather to the same shape over and over.

As industrialization and specialization solidified in the early nineteenth century, capitalists and managers pushed down wages, demanded longer shifts, and allowed more dangerous working conditions.

The Industrial Revolution came to the U.S. in earnest after the Civil War with a vast system of railroads as its centerpiece. The federal government made enormous grants of land and money to a handful of businessmen to connect the West and the South to the heart of the Union by rail.

Oil and steel magnates John D. Rockefeller (who single-handedly amassed one percent of the nation's wealth for himself) and Andrew Carnegie capitalized on this development by expanding their reach and selling materials to the builders. Hundreds of thousands of laborers worked in their factories and on the railroads for subsistence wages.

In this period of industrial expansion, politicians talked regularly about the creation of economic classes and the implications such class divisions might have for American democracy and American society.

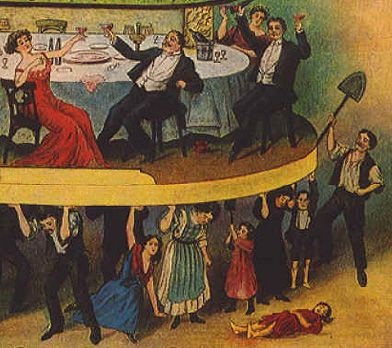

Amid intense railway construction efforts, a financial crisis in 1873 led the owners to cut wages. In 1877, railway workers went on strike. Violence spread rapidly from city to city as the railway workers' fellow wage earners joined in insurrection against the railroads. For 45 days, crowds burned and looted corporate property, stopped the trains in their tracks, and clashed with authorities.

Despite losing the popular vote in 1876, Rutherford B. Hayes was awarded the presidency through a process many regarded as corrupt (the press often referred to him as "Rutherfraud"). The winner of the popular vote, Samuel J. Tilden, campaigned by excoriating the government's ties to big business. Tilden accused the Republicans of "enriching favored classes by impoverishing the earnings of the people." Hayes campaigned for economic development of the South and currency stabilization, both of which he argued would benefit "all classes of society."

Once installed, Hayes sent federal troops to put down the labor violence and protect the railroads' property, ending the strike.

Democrat Grover Cleveland did the same thing during the Pullman strike in 1894. However, his use of federal troops to support employers sat ill with his party, and he lost re-nomination in 1896 to William Jennings Bryan, one of the most eloquent speakers to articulate the divide between the haves and the have-nots in American society.

Bryan won the Democratic party's nomination in 1896 after delivering his "Cross of Gold" speech to a thrilled convention crowd in Chicago.

He railed against the "few financial magnates who, in a back room, corner the money of the world." The definition of a "business man" should be enlarged to include workers of all stripes, he thundered, and together the people had every right to craft policies in their own favor. The question at hand was "upon which side shall the Democratic Party fight. Upon the side of the idle holders of idle capital, or upon the side of the struggling masses?"

Bryan spoke about "two ideas of government" that, in hindsight, sounds like the popular notion of trickle-down economics: "There are those who believe that, if you will only legislate to make the well-to-do prosperous, their prosperity will leak through on those below," he said. "The Democratic idea, however, has been that if you legislate to make the masses prosperous, their prosperity will find its way up through every class which rests upon them."

In the campaign of 1896, McKinley defeated Bryan with two tactics that will sound familiar. Republicans raised and spent an unprecedented $4 million—more than 10 times the amount Democrats spent and roughly $100 million today—primarily donated by wealthy industrialists such as Cornelius Vanderbilt and John Rockefeller. And McKinley's handlers played on popular fears about Bryan by connecting him to socialist and anarchist movements.

Once in office, McKinley upheld the gold standard, ignored labor, and ushered in a long era of Republican rule and prosperity. But that prosperity did not trickle down; the wealth gap grew into the next century.

Roosevelts: "Traitors" to their Class

The ensuing age of Republican dominance was not exactly corporation-friendly. When McKinley was assassinated in 1901, his vice president, Theodore Roosevelt, assumed office. Roosevelt was a progressive reformer who wanted to curb corporate control over wealth. Although from an upper-crust family himself, he rallied the working class against the accumulated wealth and power of large trusts, groups of business interests cooperating to evade competition.

As president, Roosevelt won a legal suit against J.P. Morgan's Northern Securities Company, a behemoth railroad trust, and moved against trusts in oil, sugar, tobacco, and more. While in office, he espoused a "square deal" for workers and warned against the "evils" of concentrated capital, including the possibility of an actual class war.

While Roosevelt preferred federal regulation to rein in big business, his successor, William Howard Taft, pursued legal action against trusts even more vigorously. In 1911 he successfully broke up Rockefeller's Standard Oil Monopoly.

At Osawatomie, Kansas, in 1910, Roosevelt outlined the main ideas of his "New Nationalism," on which he would run again for president—this time as the Progressive party candidate—in 1912.

The speech is considered one of the most radical ever delivered by a former president. Roosevelt compared contemporary struggles between labor and capital to the Civil War, and "special privileges" accrued by big business to slaveholding. He acknowledged the tension between the wealthy few and the working many, framing it as a contest between property rights and human rights.

But he exhorted the crowd to use democratic means to curb the power of the trusts, warning that "ruin in its worst form is inevitable if our national life brings us nothing better than swollen fortunes for the few and the triumph in both politics and business of a sordid and selfish materialism."

He heaped scorn upon the ability of magnates to purchase political power and called for tax reform: "I believe in a graduated income tax on big fortunes, and in another tax which is far more easily collected and far more effective—a graduated inheritance tax on big fortunes, properly safeguarded against evasion and increasing rapidly in amount with the size of the estate."

Roosevelt continued as a popular speaker but would never again occupy the White House. However, a federal income tax soon became constitutional law with the ratification of the Sixteenth Amendment in 1913.

During his first term (1933-1936), Franklin D. Roosevelt cut income taxes for 99 percent of American families (those earning less than $26,000 per year), but raised them for the wealthiest 1 percent. He talked about this policy while stumping for reelection in 1936, saying that "less than one percent of the heads of American families pay more than they did [in 1932]; and more than 99 percent pay less than they did, for more than 99 percent earn less than $26,000 per year … . Taxes are higher for those who can afford to pay high taxes. They are lower for those who can afford to pay less. That is getting back again to the American principle—taxation according to ability to pay."

Also born to great wealth and privilege, Teddy Roosevelt's genteel fifth cousin faced the Great Depression by experimenting frenetically with economic programs and federal spending. His "alphabet soup" of agencies (AAA, CCC, WPA, FHA, NRA, etc.) created jobs and offered outright relief to struggling Americans. FDR increased federal spending to unprecedented levels and helmed an astonishing expansion of presidential authority.

FDR displayed an exceptional sympathy for struggling Americans, crafting a populist message that pitted the "economic royalists" of an "industrial dynasty" against the mass of citizen laborers.

The Industrial Revolution, he said, had unleashed new forces in society that had been used to deprive most people of economic freedom even while leaving their political freedom intact. "A small group had concentrated into their own hands an almost complete control over other people's property, other people's money, other people's labor—other people's lives." He saw the task of democracy as wresting back the ill-gotten power of the ultra-wealthy few, and pledged to be "enlisted for the duration of the war."

Shortly after FDR's re-election in 1936, a New York Times editorial read, "No cry was more often heard in the Presidential campaign, or was more bitter, than the warning that this country stood face to face with a war between classes" by people who "charged that the New Deal had developed, whether it intended to or not, class hatred in the United States to a degree and intensity never before dreamed of here." It concluded that given the election results, such rhetoric was "quite needless and a little ridiculous."

It was indeed during the 1930s that conservatives began attaching the term "class warfare" to liberal social and economic policies.

Senator Robert Taft, an early leader of the modern conservative movement, believed the constitutional property rights of the wealthy should be protected against federal regulation, taxation, and labor unions. He saw it as more important to preserve the economic freedom of business owners than to secure equality of opportunity for everyone.

Taft put together a coalition of wealthy conservatives called the Liberty League, which aimed to paint New Deal initiatives as communistic. "The dragon teeth of class warfare are being sown with a vengeance," they said of FDR's anti-big-business stance.

It was a warning that the bloody class warfare reported from Europe—manifested most ominously in the Soviet Union but found throughout the European continent—could easily spill over into the United States. The use of the term "class warfare" would shift after World War II, when the two world powers clashed over their ideologies, capitalism and communism.

Class in the Cold War Era

The splendid economic position of the U.S. at the end of the war increased both plutocrats' profits and workers' wages. The rising tide really did lift all boats.

Harry S Truman, who became president when FDR died in office in 1945 and narrowly won a second term in 1948, mostly supported the equalizing tenets of the New Deal. But a Republican Congress overrode Truman's veto of the (Robert) Taft-Hartley Act of 1947, which repealed many of the New Deal victories labor unions had won.

"The New Deal, and now the Fair Deal, is patterned line for line from the Marxist Manifesto of shameful class warfare, out-and-out exploitation of one group in favor of another in return for votes," said Republican congressman Ralph Gwinn in 1949.

Campaigning for the White House in 1951, Dwight Eisenhower preached government cooperation with labor unions as a way to avoid class warfare. "Class warfare has too many times brought about the enslavement of labor in once free lands," he said. The American brand of trade unionism, he said, was about "competition" rather than "class warfare," a distinction that had ensured the success of both workers and industry in the United States.

Although an ever-hardening bloc of conservatives deplored Eisenhower's moderation on issues such as labor, the president was known for hobnobbing with the elite. He appointed a number of business executives to his cabinet and cut government spending by about 10 percent, formulating in 1954 tax cuts that mainly benefited corporations and wealthy individuals.

In 1955 Democrats called the Republican party "the aggressor" in a campaign of class warfare that favored corporations and the very wealthy at the expense of wage earners.

Party national chairman Paul Butler said, "there is no more harmful way of fomenting class warfare than for a political party—or a government operated by that party—to favor one group of its citizens at the expense of others, and that is what the Republican party is doing today and has done for a good many years." The report cited Eisenhower as saying that if all that Americans wanted was security, they could go to prison.

On a television interview in 1963, conservative commentator William F. Buckley said, "I think the graduated income tax is an institutional form of continuing class warfare." He said lawmakers wanted to "penalize people for making a lot of money."

In 1963, Barry Goldwater said the mood of the country was turning conservative. Americans had seen "the grand design of an all-powerful central government turn into a red-tape jungle … socialist and collectivist theories turn into open war against business and industry … radicalism turn into class warfare."

Goldwater was wrong, and suffered a stinging electoral defeat. But his and other conservatives' framing of Democrats and class war simmered through the 1960s.

Discussing class warfare in the Cold-War era could lead to accusations of Marxist, socialist, and communist leanings.

For a long time, Democrats junked the talk about corporate fat cats and taxing the wealthy that had rallied workers and farmers in the first half of the century. After pushing through John F. Kennedy's civil rights reforms, Lyndon Johnson declared a War on Poverty that aided the very lowest socioeconomic classes. He focused on the bottom one-fifth, appealing to the prosperous working, middle, and upper percentile earners to support the struggling Americans at the very bottom.

Johnson's focus on poverty—think "bottom fifth" rather than "99 percent"—was one way of pursuing New Deal-era social goals without invoking the rhetoric of big-business distrust.

Enthusiasm for expensive social programs soured along with the economy through the 1970s, and many historians have claimed that opponents of Johnson's "Great Society" linked them to racial divisions as well. Tropes such as Ronald Reagan's "welfare queen," which he first mentioned in 1976, fostered a vision of hardworking whites shouldering the burden of lazy, untrustworthy minorities.

Class warfare broke into headlines in 1978 when labor leaders, frustrated with Congress blocking labor law reform and angry at President Jimmy Carter's inability help, gave up on passing legislation in a flurry of angry protest. AFL-CIO president George Meany said business interests had "joined with the right-wing anti-labor forces, which are opposed to anything for labor, opposed to anything that would help minorities, opposed to anything that would make life a little better for the people in the inner cities. And I think it is part of a class warfare."

Frustrated UAW president Douglas Fraser resigned his post with the Labor Management Group, set up under Nixon to work out labor-management solutions and advise the White House. He told the press business leaders had waged a "one-sided class war" against society's less privileged members. "I would rather sit with the rural poor, the desperate children of urban blight, the victims of racism, and working people seeking a better life than with those whose religion is the status quo, whose goal is profit and whose hearts are cold," he said.

Reagan and "Big Government"

It would be nearly impossible to overstate the importance of Reagan's presidency in changing American attitudes about the relationships among big business, voting citizens, and the federal government. Instead of a democratically empowered majority of working masses setting policies to keep concentrated wealth in check, Reagan pitted the masses against "big government."

Reagan recast the enemy in the populist argument against entrenched power: not monopolies, trusts, or capital, but the federal government. "Farmers have to fight insects, weather, and the marketplace; they shouldn't have to fight their own government," he said in 1984.

He blamed economic hardship on Democratic programs, stating that "confiscatory taxes, costly social experiments, and economic tinkering" had cost the country dearly.

"We are going to put an end to the money merry-go-round where our money becomes Washington's money, to be spent by the states and cities exactly the way the federal bureaucrats tell them to," he said in 1980. But he did pour money into national defense, which he reportedly said "doesn't count" when trying to balance the budget.

Reagan gutted social programs and implemented a 25 percent reduction in income tax, including a reduction in the top tax rate from 70 to 50 percent. As part of his budget-slashing, Reagan dismantled Great Society programs and caught flack for waging "war on the poor," a phrase used in an open letter from religious leaders protesting the cuts in 1984.

During a presidential debate in 1984, Walter Mondale challenged Reagan on income tax fairness using George Bush as an example. "He's one of the wealthiest Americans, and he's our vice president," Mondale said. "In 1981 I think he paid about 40 percent in taxes. In 1983, as a result of [Reagan's] tax preferences, he paid a little over 12 percent, 12.8 percent in taxes. That meant that he paid a lower percent in taxes than the janitor who cleaned up his office or the chauffeur who drives him to work."

Reagan's optimism and charisma helped ensure his immense popularity. The 1980s hosted a cultural shift toward conspicuous consumption and the "greed is good" credo immortalized in the 1987 film "Wall Street." Forbes magazine first published its Forbes 400 list in 1982.

The Arguments Now

As conservative control lingered into the current century, liberals continued to invert the charge of "class warfare" by criticizing the ability of corporations to purchase favors through expensive lobbying and to push through even more favorable tax terms for the super-rich.

On the campaign trail in 2000, Al Gore called George W. Bush's tax plan "class warfare on behalf of billionaires." In 2003, journalist Bill Moyers said, "The corporate right and the political right declared class warfare on working people a quarter of a century ago, and they won." Economist Paul Krugman said Bush-era policies comprise warfare "for the rich against the middle class."

In October 2011, Mitt Romney told a group of retirees in Florida that the Occupy Wall Street protests were dangerous "class warfare," while his competitors for the Republican nomination leveled the same charge at Obama. Newt Gingrich said the president was "so committed to class warfare and so committed to bureaucratic socialism that he can't possibly be effective in [creating] jobs," while Rick Santorum refuted Obama's "class-warfare arguments" by saying, "There are no classes in America."

Karl Rove has been accusing Obama of waging "class warfare" at least since 2009. A former top advisor to George W. Bush and now political commentator for Fox News and the Wall Street Journal, Rove is renowned for his influence over public discourse. An engineer and bristly defender of the Bush tax cuts, Rove warned against Obama's fomentations in a number of recent editorials.

But Rove's efforts to turn public opinion against the principles of the Occupy Wall Street movement through painting it as "socialist" and "kooky" fell flat. It has become apparent to both candidates that voters are interested in policies that would narrow rather than further widen the wealth gap.

Rove is widely reported to have modeled himself on Mark Hanna, the crafty industrialist who managed McKinley's campaign and was widely maligned as a big-money puppeteer. (A Raleigh, N.C. newspaper editor called Hanna "an industrial cannibal … a vindictive foe of organized labor. He has crushed union after union among the thousands of his own employees.") In 2003, Moyers talked about this relationship, in which George W. Bush played the modern-day part of capital-friendly McKinley.

Contemporary commentators are fond of comparing Obama to Bryan (see recent articles in the American Spectator and the New Republic), whether to speculate that Obama can't win by appealing to the masses or to ask, as Bryan did, about the fundamental aims of the Democratic party.

Pundits recently revived the New Nationalism speech because Obama chose the same spot in December 2011 to deliver his first considered reply to Occupy Wall Street. Substituting Roosevelt's "square deal" with his "fair shot," he pointed to the shrinking middle class. Increasing inequality, he said, "distorts our democracy. It gives an outsized voice to the few who can afford high-priced lobbyists and campaign contributions, and runs the risk of selling out our democracy to the highest bidder." Roosevelt's sentiments, almost exactly.

If, as in Marx's original formulation, conflict between workers and capital is inevitable, what should be the role of government? Conservatives would recast the workers' enemy, big business, as "big government." Liberals are more apt to see the function of government as making sure the economically disadvantaged are cared for in spite of massive power imbalances in a capitalist society.

As fears of communism and socialism fade into the past, and as more Americans identify with class issues, the meanings of the term "class warfare" have become even more muddled. The barb has been especially confounding because it sticks in both directions. If we are genuinely interested in finding ways to address economic inequality, we should search for better ways as a national community to talk about the relations between our socioeconomic classes.

Brands, H.W. Traitor to His Class: The Privileged Life and Radical Presidency of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. 2008.

Brands, H.W. American Colossus: The Triumph of Capitalism, 1865-1900. 2010.

Cohen, Lizabeth. Making a New Deal: Industrial Workers in Chicago, 1919-1939. 1990.

Critchlow, Donald T. The Conservative Ascendancy: How the Republican Right Rose to Power in Modern America. 2011.

Friedman, Thomas. The World Is Flat. 2005.

Kloppenberg, James T. Reading Obama: Dreams, Hope, and the American Political Tradition. 2012.

Nunberg, Geoffrey. "Class Dismissed," in Going Nucular: Language, Politics and Culture in Confrontational Times, pp. 144-47. 2004.

Phillips-Fein, Kim. Invisible Hands: The Making of the Conservative Movement from the New Deal to Reagan. 2009.

Weisman, Steven. The Great Tax Wars. 2002.