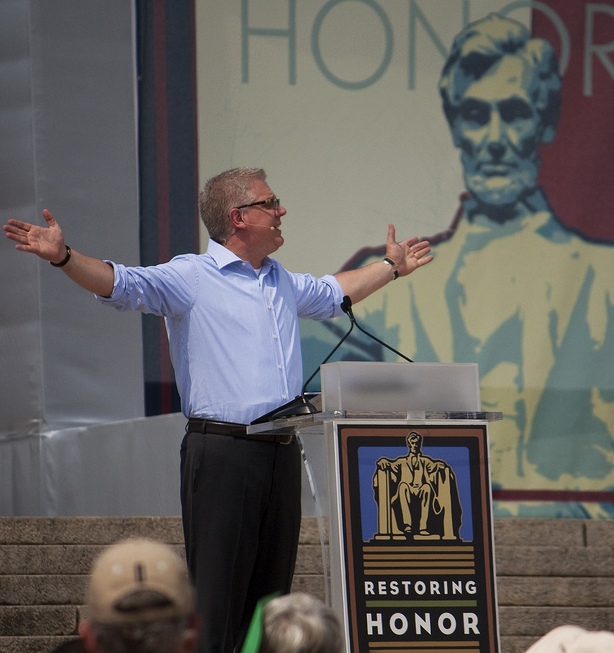

Fox News commentator and Tea Party favorite Glenn Beck addresses supporters at his "Restoring Honor" rally in Washington, D.C. on August 28, 2010. Although American "populism" has changed in its specific political views over time, the term has often been used to describe popular movements of anger against elites who are regarded as stoking the struggles of ordinary Americans. (Photo by Luke X. Martin)

The Populists are back! Since the late 19th century, 'populist' is the name we've given to any American political movement that challenged either of the two major parties. But who are they, exactly? And what does the label actually mean? And how has the meaning changed over the centuries? This month historian Marc Horger looks at the history of the term to put the current crop of populists in historical perspective.

Readers may also be interested in these recent Origins articles about current events in the United States: Why We Aren't 'Alienated' Anymore, Presidential Elections in Times of Crisis, The Debate Over Illegal Immigration, Detroit and America's Urban Woes, the Mortgage and Housing Market Crisis, the 2nd Amendment Debate, and In The Scope, a WNYUNews podcast about the history of political parties, featuring Marc Horger.

On February 11, 2010, the late Washington Post political columnist David Broder puzzled and amused left-leaning portions of the political blogosphere with a column praising the strategic savvy and tactical competence of abdicated Alaska governor Sarah Palin.

Broder had been impressed by her recent address to the National Tea Party Convention, one of the sundry right-wing "tea party" groups to spring up in the wake of Barack Obama's inauguration, during which she displayed what he called "her pitch-perfect populism." (Watch the speech here. During the question-and-answer session, she checks the notes written on the palm of her hand.)

"Her invocation of 'conservative principles and common-sense solutions' was perfectly conventional," Broder admitted. But that was beside his point; Broder was more interested in "the skill with which she drew a self-portrait that fit not just the wishes of the immediate audience but the mood of a significant slice of the broader electorate…. she has locked herself firmly in the populist embrace that every skillful outsider candidate from George Wallace to Jimmy Carter to Ronald Reagan to Bill Clinton has utilized when running against 'the political establishment.'"

What kind of magic lasso is "populist," that David Broder can throw it over those five immensely different politicians simultaneously?

Can it possibly be the same term used to describe Tom Watson, William Lamb, and William Jennings Bryan in the 1890s? Can it be reconciled with the "prairie populism" sometimes attributed to Lyndon Johnson and Hubert Humphrey, and/or the old-school conservative isolationism of Pat Buchanan, and/or Albert Gore, Jr., Harvard Class of 1969, and/or the entire 1972 Democratic Presidential field, give or take Scoop Jackson? Is it a useful description of the political reality represented by any of these figures?

Does the label "populist" help us understand Sarah Palin, or the group of people she addressed that night in Nashville? Does it matter that she had notes written on the palm of her hand?

The Original Populists

From its first appearance in the political vernacular, "populist" has been an adjective expressing an attitude—a popular anger against elites perceived as distant from and antagonistic to the struggles of ordinary Americans—more than delineating a coherent set of political beliefs.

The usage of "populist" began in 1892, as a secondary means of referring to the southern and western political insurgency that actually called itself the "People's Party," and which fielded third-party challengers to Republicans and Democrats in many states in 1892, 1894, and 1896.

These original Populists were largely farmers from the cotton, wheat, and corn belts. And they were responding to recent economic changes which simultaneously depressed the value of their commodities and plunged them into ruinous debt at the hands of banks, mortgage companies, and furnishing merchants.

Their policy demands were statist. They demanded 1) inflationary monetary policy, 2) state-run, state-subsidized systems of commodity credit and storage, and 3) state regulation of the transportation network through which their commodities flowed to market. They wanted the government to print paper money, monetize silver, store their crops, and aggressively regulate—some Populists went so far as to say nationalize—the railroad and telegraph networks. They also sought direct election of Senators and a national income tax.

In other words, these original Populists saw large-scale government intervention as the solution to their economic problems.

They were regarded at the time as dangerous radicals, particularly by the traditional machine politicians they sought to upend, and by the laissez-faire bankers and businessmen they identified as their economic enemies. Nevertheless, many of their "radical" demands had come to pass by 1916 or so.

But the original Populists were also making an argument about their own centrality to American life, and they were doing so at more or less the exact historical moment it was no longer true. The insurgents had a reasonable grasp of what was happening to them economically, but for complex cultural reasons they believed that it could only be happening to them as the result of conspiratorial action taken at great physical and moral distance from themselves.

They were farmers; they were producers; they were the People; they lived in a democracy; they ruled. They could only be losing as a result of subterfuge and blackguardism perpetrated by villains from the East Coast.

One of the most popular and compelling works of Populist political persuasion—an anti-gold standard monetary treatise called Coin's Financial School—offers a glimpse of this worldview.

It described the 1873 demonetization of silver—largely unnoticed and uncontroversial at the time—as the "Crime of 1873," and argued that only the full and unlimited re-monetization of silver at traditional fixed ratios could reverse the conspiracy against producers. Its titular hero made the case by tutoring a classroom of economists, bankers, newspaper editors, and other gold-bug city slickers in the unassailable logic of bimetallism. All are convinced. [Read here for more on the history of currency and today's currency wars]

It also featured a cartoon depicting a Bunyonian cow, the size of the nation, being fed corn and wheat by suffering farmers in the south and west and milked by top-hatted, stripey –panted elites in New York and Boston. The milk buckets had dollar signs on the side.

Surely the answer to such a problem was something called the People's Party.

This self-image was deeply shaped by the Jeffersonian agrarian romanticism which permeated their politics, and indeed their lives. James "Cyclone" Davis, one of the most colorful and effective Populist stump speakers, carried with him an edition of Jefferson's works from which to select thunderbolts suitable for hurling at the farmers' foes.

Jefferson told them that, as farmers, landowners, and producers, they were the backbone of the nation. So did Cyclone Davis, and most of their other political leaders, and their newspaper editors, and their school primers. Everything in their experience told them they were the People, and were the "real" America.

They were nevertheless living through the historical moment at which industrialization, urbanization, and immigration began to knock rural producers out of the center of American culture.

America, as historian Arthur Meier Schlesinger famously wrote, was born in the country and moved to the city. He was referring to the 1880s and 1890s. The United States may not have been moving as the result of a conspiracy, but small farmers in the south and west were not wrong to perceive the country was moving away from them economically and politically.

Though "populists" and "populism" have subsequently come in many flavors, a few generalizations characteristic of the original Populists have usually remained true.

First and foremost, contemporary use of the term assumes there is anger somewhere in the room. This anger may be justified or irrational; organic or ginned-up; economic, racial, cultural, or regional; but without palpable anger and resentment, most observers would probably choose different terminology. This anger and resentment is usually directed at "elites," and these elites are usually economically, socially, and/or geographically distant.

Second of all, populism is generally construed as a strategy or technique of political persuasion rather than a matrix of beliefs. It is a method of identifying a villain and shaking a fist. This is so even if it also reflects real policy choices. "Raise marginal tax rates on high earners" is a policy choice. "Tax the rich" is populism.

Finally, populist political labeling usually implies someone is deliberately creating or highlighting a perception of status differential. This is a partial consequence of defining an in-group not just against an out-group, but against an "elite."

Virtually all effective political communication involves defining an in-group versus an out-group, an us versus a them. But a populist politics stipulates a people against a plutocracy, or defends "real Americans" from condescension, or condemns a haughty elite looking down its collective nose in contempt at ordinary folks.

Populism and the Great Depression

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, a number of public figures revived the combination of anti-elite animus, visceral distaste for banking and corporate finance, and bold demands for government action on behalf of ordinary people which had been characteristic of the original Populists.

One of them, of course, was Franklin Roosevelt, whose New Deal programs intervened aggressively in wide swaths of American economic life and rearranged national political coalitions for a generation or more. Roosevelt defended the New Deal with increasingly anti-elitist political language, particularly after 1935 or so, when he began to welcome the hatred of "government by organized money" and sharpen his rhetorical attacks on "economic royalists."

This combination of policy and rhetoric is widely credited by historians and political scientists as having created the modern definition of "liberalism" within the Democratic Party, disconnecting the term from 19th century concepts of laissez-faire and aligning it with robust use of government power in the perceived public interest.

Several contemporary critics of Roosevelt, however, threatened to build new mass movements of their own by combining anti-elite rhetorical tropes and demands for economic relief with conspiratorial hyperbole, appeals to status anxiety, and attacks on Roosevelt and the New Deal.

One was the colorful and charismatic Huey Long, who built a powerful political machine around himself as governor and then Senator from Louisiana. A Democrat, he supported Roosevelt in 1932, but turned on the Administration almost immediately upon reaching Washington in 1933.

He began building a national following for himself by declaring "Every Man a King" and founding a series of "Share Our Wealth" societies around the country in support of his aggressively redistributionist economic schemes—and, most contemporary observers believed, his own Presidential aspirations. He was assassinated in 1935 before these ambitions could be tested, but he was nevertheless regarded by Time magazine (and others) as a potential dictator and demagogue.

So was Father Charles Coughlin, a Catholic priest from a working-class suburb of Detroit who used a radio network to build a national following. Coughlin's radio sermons combined fervent anticommunism with demands for social justice, a spirited defense of the economic aspirations of ordinary people, and scathing attacks on the illegitimacy of international banking and monetary policy.

Like Huey Long, he had initially supported Roosevelt and then changed his mind; like Long, he spoke to many of the same people Roosevelt was trying to bundle into the New Deal coalition; like Long, he struck some observers as a potentially dangerous force.

His attacks on communism and international banking grew more conspiratorial, and more anti-Semitic, as the 1930s progressed. By the end of the decade, he was republishing portions of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion in his national newsletter. He was finally pulled off the air by the Archbishop of Detroit in 1941. He has subsequently become synonymous with political demagoguery via mass media.

From an economic and demographic standpoint, Long and Coughlin spoke to many of the same political constituencies Roosevelt did, and about many of the same things: the universality of economic aspiration, the redistribution of economic privilege, the Depression as a set of structural, rather than personal, failings.

The original Populists had spoken this way. And like the original Populists—but unlike the largely upbeat and optimistic Roosevelt—Long and Coughlin spoke in discontented and conspiratorial tones.

Richard Hofstadter and the Paranoid Critique of Populism

Liberal intellectuals, who have rather well-rationalized systems of political beliefs, tend to expect that the masses of people, whose actions at certain moments in history coincide with some of these beliefs, will share their other convictions as a matter of logic and principle. Intellectuals, moreover, suffer from a sense of isolation which they usually seek to surmount by finding ways of getting in rapport with the people, and they readily succumb to a tendency to sentimentalize the folk.

-- Richard Hofstadter, The Age of Reform, 1955

That the practice of politics might have psychological dimensions held greater significance for observers after 1945. The Great Depression, World War II, and Cold War generated a completely new set of intellectual contexts within which mass movements built from anger and resentment were compared to one another.

The basic irrationality at the root of the inter-war European political regimes that triggered World War II, and the near moral insanity of the war itself, caused many postwar historians and political scientists to consider the possibility that politics was best understood psychologically rather than economically.

The most prominent historian among these postwar intellectuals was Columbia's Richard Hofstadter, who began the process of re-interpreting American political history away from a story of economic conflict—as most other historians of his generation had been trained to do in the 1920s and 1930s—and toward a story of status conflict, sublimated anxiety, and social psychology contained within a framework of relative economic and ideological consensus.

The original Populists emerged from this re-interpretation severely bloodied. His 1948 book, The American Political Tradition and the Men Who Made It, contained a savage deconstruction of the career of William Jennings Bryan, champion of free silver and the 1896 People's Party and Democratic Party joint Presidential nominee.

(A sample, from the concluding paragraph, reads: "So spoke the aging Bryan, the knight-errant of the oppressed. He closed his career in much the same role he had begun it in 1896: a provincial politician following a provincial populace in provincial prejudices.")

In 1955's The Age of Reform, he focused on the self-delusional consequences of the Populists' commitment to a Jeffersonian "agrarian myth," pointed out the anti-Semitic overtones of their anti-banker, anti-gold standard monetary harangues, and described their conspiratorial political worldview as an irrational "folklore of Populism."

In 1963's Anti-Intellectualism in American Life, he extended small-p populist political tendencies backward and forward to explain a wide variety of political and cultural tendencies inherent in his title. These books received wide general readership, and the last two won Pulitzer Prizes.

Meanwhile, Hofstadter was throwing many of the same punches at what he and many other postwar liberal intellectuals began to call "The New American Right": Joe McCarthy and his supporters, the John Birch Society, and, after 1964, the Goldwater wing of the Republican Party.

His essays "The Pseudo-Conservative Revolt" (1954), "Pseudo-Conservatism Revisited" (1964), and "The Paranoid Style in American Politics" (1964) examined what Hofstadter called the "status politics," rather than "interest politics," of a set of conspiratorially-minded political movements which, he assumed, his readers would naturally regard as right-wing fringe groups self-evidently detached from reality.

These essays were eventually anthologized as The Paranoid Style in American Politics, which also contained Hofstadter's "Free Silver and the Mind of 'Coin' Harvey," about the Populist pamphleteer from 1894 who brought you the giant cow.

If psychological motivations trump economic motivation in your philosophy of history, the Populists represent a problem. While admitting they had legitimate economic complaints and contributed meaningfully to a salutary tradition of political reform, Hofstadter nevertheless saw them in the same psychological terms he saw McCarthyites and John Birchers.

He viewed Huey Long and Father Coughlin in much the same way. They were at factual and psychological odds with modernity, and they had more in common with a right-wing, anti-intellectual American political tradition than they did New Dealers or postwar liberals.

To Richard Hofstadter—and to many other intellectuals in the postwar period for whom World War II had been about the moral fate of the Atlantic world—the folly of building political coalitions out of anger, particularly a conspiratorial anger at odds with objective reality, was the self-evident historical lesson of the twentieth century. This way led to future fascisms.

For many Americans, however, the war had been about American nationalism in the Pacific, and the self-evident historical lesson of the twentieth century was the existential threat "Godless Communism" posed to the American Way of Life. To these Americans, Joe McCarthy and Chiang-Kai-Shek seemed plausible freedom fighters; Alger Hiss and Dalton Trumbo seemed the worst kind of subversives; the New Deal seemed in retrospect like twenty years of treason.

Hofstadter, and other liberal anti-McCarthy intellectuals of his generation, were not wrong to perceive that such people lived in a different moral universe from themselves, especially if they also lived in homes financed by G.I. Bill mortgages.

Hofstadter devoted much of his career as a public intellectual to making this case about the American right wing, and this shaped not only his interpretation of Populism, but also the way liberally-inclined intellectuals who subsequently deployed "populist" as an adjective to describe contemporary political behavior.

Liberal critics looking to score points against post-2008 tea partiers and "movement" conservatives—for whom "socialism" is both a swear word and an omnipresent, misunderstood specter—will find much to nod at in agreement in The Paranoid Style in American Politics.

George Wallace: Populism in the Civil Rights Era

When the Civil Rights and Warren Court revolutions of the 1960s began to unravel the New Deal coalition and reshuffle the national political deck, potentially "populist" political appeals and strategies began to appear in all corners of American life.

Working-class and/or southern white voters previously taken for granted as Democrats were now viewed as potentially up for grabs. Many of the persuasive methods used to target them sought to play on the status anxieties unleashed by the destruction of the racial caste system and the emergence of Baby Boomer youth culture. The Thomas Edison of thinly coded white resentment is George Wallace – or, more specifically, the George Wallace who ran for President in 1968 and 1972.

The George Wallace who, as governor of Alabama in 1963, proclaimed "segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever" and stood in the doorway of the University of Alabama in an attempt to prevent its integration did not require much national contemplation. He was a segregationist, and his white resentment was not veiled.

The one who ran disturbingly well among working-class white northerners as a third party candidate in 1968, and disturbingly well in Democratic primaries outside the south in 1972—second in Pennsylvania, second in Wisconsin—before his near-assassination was another story.

That Wallace pioneered much of the coded anti-elitist rhetoric subsequently used by many politicians to talk to conservative white voters about civil rights and/or racial issues while leaving some plausible deniability against accusations of racism.

"Why are more and more millions of Americans turning to Governor Wallace? Follow as your children are bused across town," declared one TV political advertisement, in reference to school desegregation. "As President, I shall, within the law, turn back the absolute control of the public school systems to the people of the respective states."

He was deeply skilled at heightening, and directing, what we referred to earlier as "the anger in the room." He sensed that many of his potential supporters felt that they were being looked down on as rubes and bigots by people like, well, like Richard Hofstadter. They were not wrong.

Effective exploitation of this dynamic of presumed contempt attributed to your enemies in the "cultural elite" has become a basic building block of the rhetoric of "populist" conservatism. One consequence of Wallace's influence is the long-standing tendency of conservatives to use code and proxy when talking about race, and the long-standing tendency of liberals to scour conservative political rhetoric for signs they are really talking about race.

This tendency has diminished over time, but never really gone away. Anytime a white conservative uses the word "elite" as an epithet, or attacks the federal government as a distant, tyrannical force, the George Wallace Buzzer still goes off in the heads of many nearby liberals.

An additional consequence of Wallace's influence is the degree to which "populist" appeals and strategies are almost always conceived as appeals to working- and middle-class whites, even when articulated by liberal Democrats for liberal purposes. Virginia Senator Jim Webb's efforts to convince Democrats to speak more directly to upland, Scotch-Irish southerners on an economic basis suggests one example. Former Ohio governor Ted Strickland's 2010 re-election campaign suggests another.

Reconsidering Populism: Lawrence Goodwyn

Nevertheless, a post-Hofstadter, post-Wallace, post-1968 vision of the original Populists as potential political role models for the left does exist. It has its roots in historian Lawrence Goodwyn's Democratic Promise: The Populist Moment in America, from 1976.

Goodwyn re-interpreted Populism as a lost opportunity of potentially transformative democratic potential. Goodwyn was moved not by Populist monetary policy or political rhetoric, but by what he considered its organically grassroots "movement culture" of economic cooperation and collective uplift.

Writing in a post-civil rights intellectual environment—in which historians were both more interested in race and class and less afraid of economic or cultural radicalism than the previous generation had been—Goodwyn placed the core of Populist culture in the south, rather than the west, and saw in it the possibility of transformative change unrealized.

The fact that bankers and machine politicians considered them dangerous radicals was a feature, not a bug. Some Populists had made sincere efforts to unite black and white southern farmers on an economic basis against the culture of white supremacy, and at the very height of the 1890s. Some Populists had made sincere efforts to unite farmers and wage workingmen as fellow producers with shared enemies.

The aspects of Populism Hofstadter had criticized most severely, especially the movement for free silver, were, to Goodwyn, barely even Populism at all. They were elements of a "shadow movement," a narrow co-option of what had once been a much broader movement with greater transformative potential.

For Goodwyn, in fact, the most important and inspiring Populist contribution to American society had occurred before they had even become Populists. It was the cooperative "movement culture" of the Farmers' Alliance purchasing and marketing cooperatives of the 1880s—from which the political apparatus of the People's Party eventually sprung—that represented the real opportunity to deflect American culture down a path not taken.

Culture, in fact, rather than psychology or politics, was Goodwyn's real subject, and he believed the real power in the 1890s lay in the ability of Populism's foes to narrow the horizon of the possible. "It is essential to recognize," Goodwyn wrote, "that Populism appeared at almost the very last moment before the values implicit in the corporate state captured the cultural high ground in American society itself." Its failure represented to Goodwyn a permanent constriction of what kinds of social organization were imaginable.

Of course, many intellectuals of Hofstadter's generation had specifically argued that the spectrum of permissible American social and economic thought was relatively narrow, and they meant it as a compliment. Intellectuals who experienced 1968 firsthand, but not 1945, were less likely to see it that way.

These, then, are the farthest poles of Populist as adjective, and Populism as political style. Populism as a grassroots culture; Populism as an ideology. Populism as an expression of optimism and potential; Populism as an expression of status anxiety.

Populism as the opportunity to build new, more wholesome coalitions and challenge the imaginative constraints of the old politics; Populism as George Wallace's brother-in-law and Joe McCarthy's cousin once removed.

When liberal strategists and commentators argue for more and more effective populism from the Democratic party, they have something like the former in mind. When the left-leaning, satirical online magazine Wonkette.com breaks out the "Get a Brain! Morans" jpeg, they mean the latter.

The Tea Party and Populism

Wonkette has been living in a target-rich environment lately. Two real-world developments, combined with two media events, appear to be responsible for the current batch of disparate "tea party" conservative groups which have caused so many observers to re-thumb their old paperback copies of The Paranoid Style.

The real-world events are the election, by a comfortable margin, of Barack Obama to the Presidency and the severe economic crisis he inherited upon reaching the White House.

The media events are this apparently spontaneous outburst by CNBC reporter Rick Santelli on the floor of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange in February of 2009, in which Santelli blames overextended borrowers, and not banks or bond markets, for the subprime mortgage crisis while pit traders cheer him on; and the shift of Glenn Beck's television program from CNN Headline News to Fox, where it premiered the week of Obama's inauguration.

The resulting tea party groups are widely credited with both reinvigorating the Republican Party and threatening its internal cohesion.

Does "populism" describe these tea party groups in a meaningful way? Not everyone thinks so. Certainly, they are hard to conceptualize as populists if your frame of reference is economic.

Examine, for example, the platform of the Maine Republican Party, which was shanghaied by state tea party groups this summer and then ridden to victory by new Republican governor Paul LePage. Does it bear any relationship to the practical economic concerns of the recession, except to the extent it demands the government stop doing anything about it?

The most consistent policy preference articulated by these various groups, in fact, appears to be opposition to robust government action of any kind. Government response to the recession has been quite robust, and this is a primary source of tea party anger.

The major works of Richard Hofstadter are The American Political Tradition and the Men Who Made It (1948), The Age of Reform (1955), Anti-Intellectualism in American Life (1963), and The Paranoid Style in American Politics and Other Essays (1965).

David Brown's Richard Hofstadter: An Intellectual Biography (2006) offers a recent interpretation of his impact. Alan Brinkley's "Richard Hofstadter's The Age of Reform: A Reconsideration," Reviews In American History, Vol. 13, No. 3 (September 1985), pp. 462-480, offers a slightly older one. The anthology The New American Right (1955), edited by Daniel Bell, presents Hofstadter's work in the context of other post-WWII critics of American "status" politics.

Michael Kazin's The Populist Persuasion (1995) traces the impact of Populism on American politics since the late 19th century. See also his A Godly Hero: The Life of William Jennings Bryan (2006) for a more positive take on Bryan than Hofstadter had to offer.

Worthwhile histories of the original Populists include Lawrence Goodwyn's Democratic Promise (1976), Charles Postel's The Populist Vision (2007), and, provided you take their age into consideration, John Hicks' The Populist Revolt (1931) and C. Vann Woodward's classic Tom Watson: Agrarian Rebel (1938). See also Edward Ayers' The Promise of the New South (1992) for Populism in the Southern cultural and political context.

Alan Brinkley's Voices of Protest: Huey Long, Father Coughlin, and the Great Depression (1982) covers anti-Roosevelt populism in the 1930s. Warren Donald, Radio Priest: Charles Coughlin, The Father of Hate Radio (1996) and William Ivy Hair, The Kingfish and His Realm: The Life and Times of Huey P. Long (1991) are more recent biographies.

On George Wallace, see Jody Carlson's George C. Wallace and the Politics of Powerlessness : The Wallace Campaigns for the Presidency, 1964-1976 (1981) and Dan Carter's The Politics of Rage: George Wallace, the Origins of the New Conservatism, and the Transformation of American Politics (second edition, 2000).