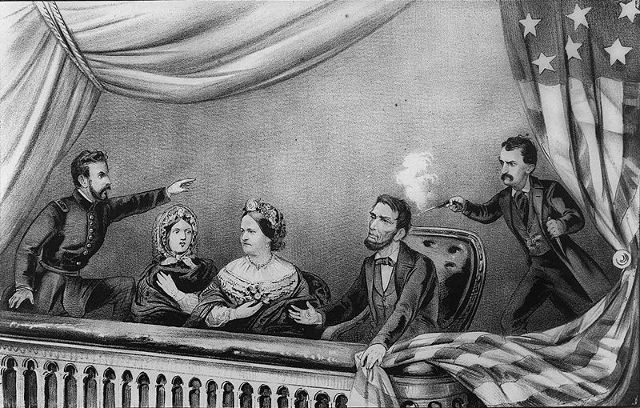

On April 14, 2015, we observed the 150th anniversary of President Abraham Lincoln’s death. Leader of the North in the Civil War, orator of the Gettysburg Address, described by some as the liberator of the slaves, Lincoln continues to have a strong hold on the imagination of the American public. To commemorate “Honest Abe,” Origins offers ten of the most important things to know about his presidency, his assassination, and his legacy.

1. Presidents Killed in Office

|

| President John F. Kennedy addresses nation on civil rights. June 11, 1963. |

Lincoln was the first American President to be killed in office. His death was a public trauma, obvious in the intense, widespread outbursts of grief, vividly described in the diary of Gideon Welles, Lincoln’s Secretary of the Navy, among other sources. Subsequently, assassins also felled James Garfield (1881), William McKinley (1901), and John F. Kennedy(1963). JFK’s murder was a touchstone for anyone who was alive at that moment. Lincoln’s passing made a similar imprint on his generation.

2. The Scholarship on Lincoln

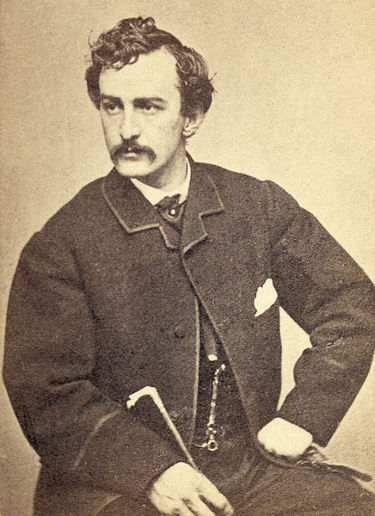

|

| John Wilkes Booth, 1865 |

While there are hundreds of biographies of Abraham Lincoln, professional historians have published surprisingly little on the assassination. The subject appeared to offer nothing of interest, since the murderer proclaimed his identity to a stunned audience in Ford’s Theatre. Non-academic writers have uncovered new details about Booth’s circle, such as the number of people who knew he was planning to kidnap or kill Lincoln (about twenty-five). The first biography of John Wilkes Booth by a professional historian, Terry Alford, will appear this year.

3. The Setting

|

| Ford's Theatre |

The American public has remained fascinated with Lincoln’s death, beginning with where it happened. Attending the theatre was one of the President’s only forms of recreation, and John Wilkes Booth, an actor from a prominent family of actors, was a rising star. In 1864, Booth evidently began to believe he was a character in one of Shakespeare’s plays and concluded that he would slay the man he called a tyrant. A murder in a theater is literally dramatic, and the timing was Biblical, since Lincoln was shot on Good Friday.

4. The People Connected to the Assassination

|

| Mary Todd Lincoln was never to recover from the murder at Ford's Theatre. |

A riveting group of people, all of them interesting in their own right, are forever associated with the events at Ford’s Theatre: his troubled wife Mary, who never recovered from witnessing his murder; the young couple in the Presidential box, Clara Harris and Henry Rathbone, who were last-minute replacements for Ulysses S. Grant and his wife; the Booth brothers of Maryland, divided politically like so many Border State families; Edwin Booth, the family’s most famous actor, an ardent unionist and friend of the man his brother assassinated.

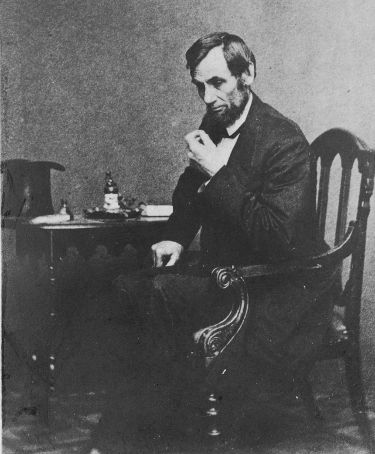

5. Lincoln as a Human Being

|

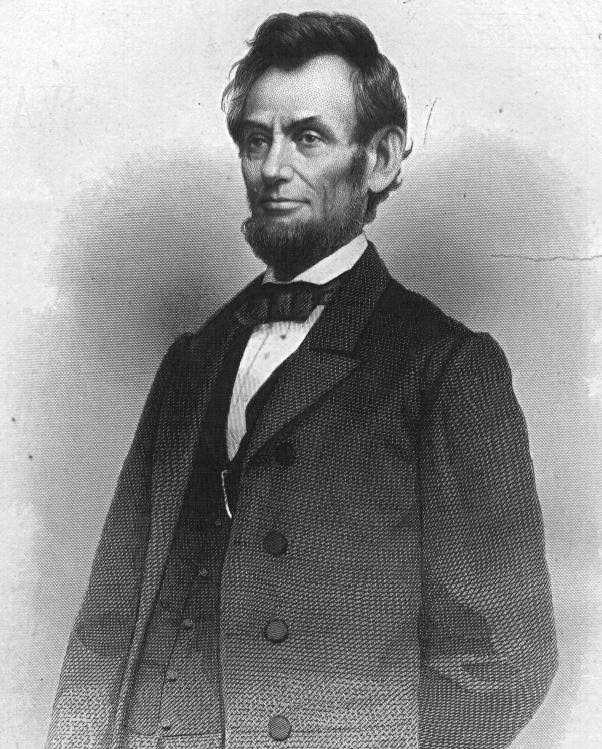

| Abraham Lincoln, 1861 |

Abraham Lincoln remains an enigma. He left few documents on his inner life, and he confided in few people before or after 1861. Other Presidents who achieved ground-breaking legislation, such as Franklin D. Roosevelt and Lyndon B. Johnson, created much more documentation about their decision-making. Lincoln wrestled with the biggest questions himself, leaving a few glancing comments about such landmarks as the Emancipation Proclamation. There are the other, related paradoxes of his personality: likable yet hard to get to know; a self-educated man who was one of the most gifted writers to serve in the White House; and a native of the Upper South who ended slavery.

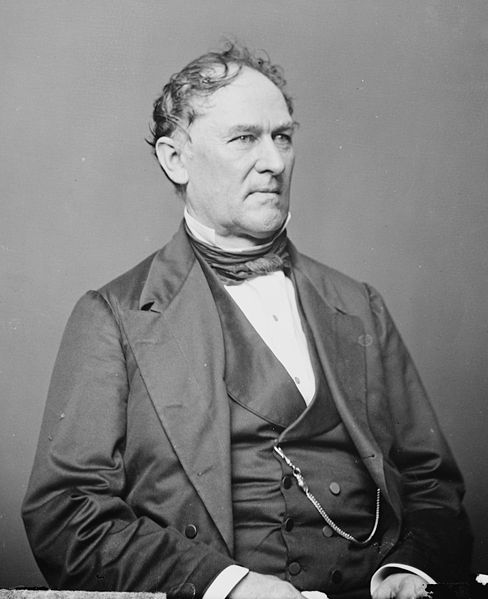

6. Lincoln as a Politician

|

| Orville Browning of Illinois |

The President demonstrated an extraordinary set of political skills. Uniting the North was a challenge in itself, since he received less than half of the popular vote in 1860. Yet he developed the ability to persuade the Northern public that he was on the right course, and he was re-elected in 1864. He did not allow dissent within the Union to undermine the war effort, and he learned to deal with difficult personalities in his Cabinet (William Seward), the Senate (Orville Browning), and the press (Horace Greeley).

7. Lincoln as Emancipator

|

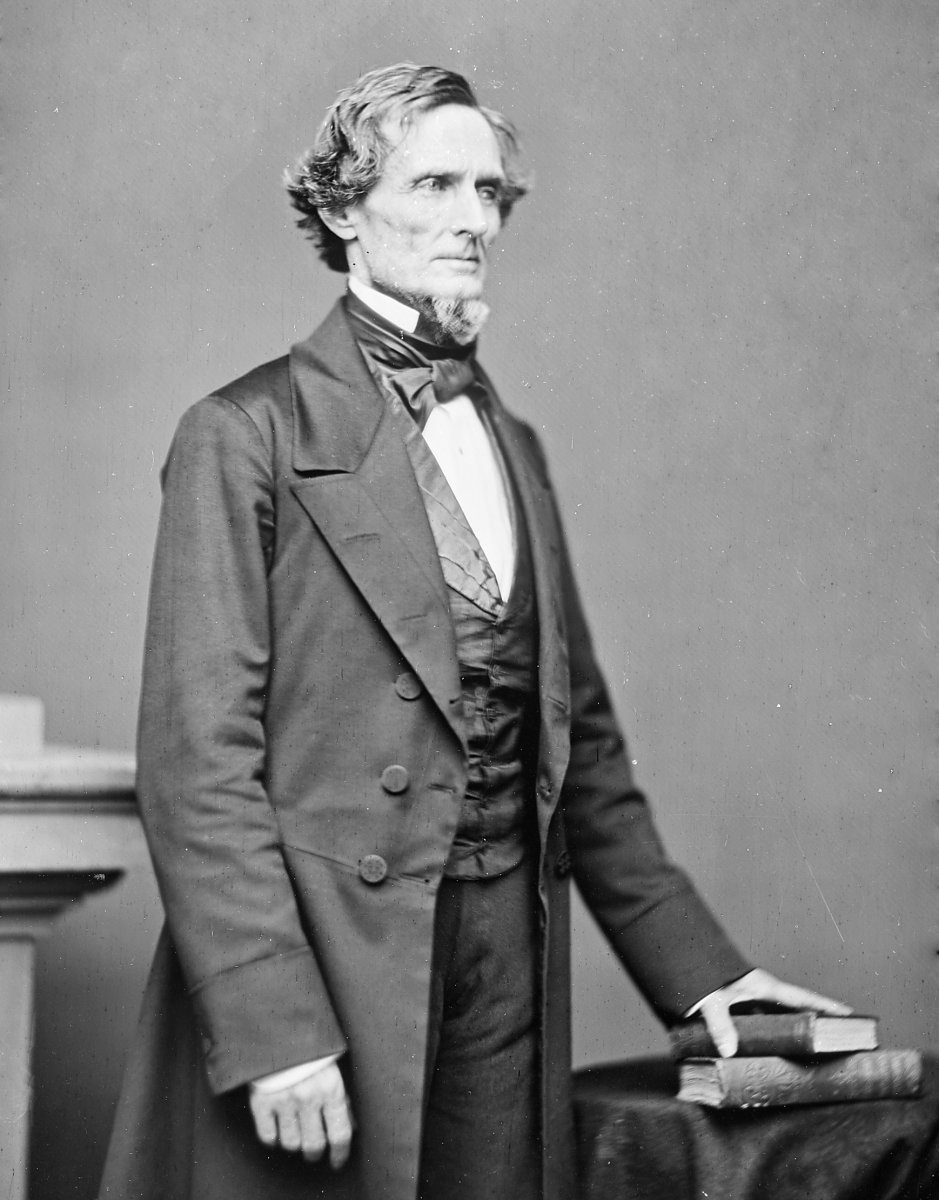

| Jefferson Davis as photographed by Mathew Brady, 1861 |

All the while, he had to wage war against a determined foe who would not yield even when Lincoln offered the Confederacy gradual, compensated emancipation in 1862 and again in 1865.

Abolishing slavery was more difficult in the United States than in any other slave society of the New World, because only in the U.S. did slave owners go to war to preserve slavery. Historians still debate whether he was the indispensable agent of emancipation, with some scholars emphasizing the role of the federal army or the slaves themselves, but most historians think he was a central player, if not the central player in the process.

8. Lincoln’s Successors

|

| Lyndon B. Johnson signs the Voting Rights Act of 1965 |

Lincoln was followed by a generation of mediocre, corrupt Presidents who did not come close to him in terms of ability. Two full generations passed before another highly-skilled politician, FDR, began to take up issues of racial equality. An entire century passed before Lyndon Johnson completed Lincoln’s work of dismantling the legal barriers to racial equality at the national level. That meant a hundred years of discrimination against African-Americans and the most blatant violations of American ideals of equality.

9. Lincoln and Partisanship

|

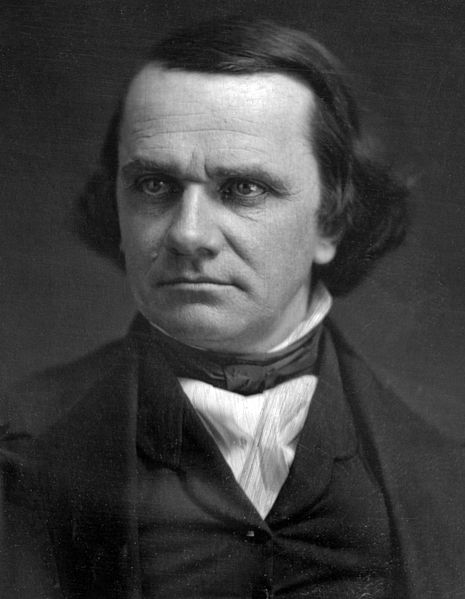

| Stephen A. Douglas photographed by Mathew Brady |

The President was openly partisan without demonizing the opposition. He supported the philosophy of the Whig Party and later the Republican Party—that a dynamic federal government should take action to benefit the public, at the expense of the states if necessary. (In his lifetime, the Democratic Party advocated states’ rights.) Yet he welcomed the support of Democrat Stephen Douglas in 1861 and other Democrats who supported some of his measures. He accepted the legitimacy of the two-party system, even as he vigorously pressed his case within the system.

10. The Renaissance in Lincoln Studies

|

| Abraham Lincoln, 1864 |

Over the last twenty years, we have witnessed a dramatic resurgence in scholarship on Lincoln. Is it an accident that this resurgence began in the 1990s, when national politics became poisoned with a crude partisanship coming largely from members of Lincoln’s own party? Topics rise and fall for a host of reasons, as historians know, and it is hard to draw a straight line from contemporary issues to renewed scholarly interest in the President’s life. Maybe it is just a coincidence that this burst of scholarship began in an age of bitter political hatred. Lincoln nevertheless showed a rare combination of executive ability and human wisdom that the public still longs for a hundred and fifty years after his death.