When historians construct narratives about the past they exclude as well as include—and nowhere is that more apparent than in the way Native people have been erased from most histories of the United States. This month, Geographer Deondre Smiles (Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe) invites us to reexamine the conventional stories Americans tell themselves from a Native point of view. At stake is not only a fuller understanding of our history but, as Smiles notes, a people erased from the past are easily erased from the present also.

“We birthed a nation from nothing. I mean, there was nothing here...I mean, yes we have Native Americans but candidly there isn't much Native American culture in American culture.”

—Rick Santorum, April 2021

Former Pennsylvania senator (and CNN commentator) Rick Santorum made those comments at a conservative student organization-hosted conference. They were given as part of a speech about the beginnings of what we now call the United States, and they have garnered criticism and controversy from a wide spectrum of American society. He is now an ex-CNN commentator.

Rick Santorum giving a speech at the Young American Foundation event, 2021.

Santorum’s comments were rightfully criticized as being dismissive of a long history of genocide in the United States against Native peoples and cultures, as well as being historically ignorant. We must call this sort of behavior out when we see it.

However, Santorum’s comments point to a much deeper structural myth of the treatment of Native peoples in the United States that Americans have constructed over time. What I mean by this, is that American history has been constructed in a way that completely ignores Indigenous histories and Indigenous presence upon the lands that we now call the “United States.”

In constructing such a history, we conveniently ignore that land theft and Indigenous erasure have quite literally shaped the development of this country. We’ve been conditioned to accept this “whitewashed,” Indigenous-free accounting of the past as a “given” in American history and the construction of this country. And the implications of this historical erasure have been profound for how we view the very presence and role of Indigenous peoples in contemporary American society.

Let’s take this structural myth that Santorum presented, break it apart into its constituent pieces, and explore the histories that have given rise to it. Engaging with these histories head-on will open our eyes to facts that run counter to Santorum’s claims.

The United States was not built out of nothing, and the fact that Indigenous cultures are not part of the dominant American “culture” is a calculated action. And this erasure does not mean that Native cultures do not exist, or that our relationships with the lands on which this settler colony is built are any less valid.

“Birthing a Nation from Nothing”

Many Americans believe the lands that comprise the United States have a fairly recent history of human habitation. If one was to ask a group of Americans to name a few of the formative events in American history, they would be likely to hear Christopher Columbus “discovering the New World” (not exactly related to the United States nor historically accurate but never mind); Pilgrims arriving at Plymouth; the Declaration of Independence and Revolutionary War; the Civil War; and the opening/settling of the West.

American Progress (1872) by John Gast

I want to focus on the last example, the “opening” of the American West. But before I do that, let me outline a key term: settler colonialism.

This was a distinct form of colonialism built upon the settlement of a geographic space by non-native people and the displacement of the Indigenous communities who lived in that space. Rather than more extractive forms of “resource colonialism,” where the goal was to exploit natural resources until those resources ran out, the settler colony was meant to be permanent.

Of course, the settler colony could also center around resource extraction, but the larger goal of settler colonies is to control the space. Scholars consider the United States a settler colony along with Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Israel, and others.

Let’s return to the “opening” of the American West where, in the standard telling, settlers and “pioneers” pushed forward and westward from the original 13 states across the Appalachians towards the Mississippi and eventually the Pacific Ocean, forming new settlements in new territories.

Daniel Boone Escorting Settlers through the Cumberland Gap (1851–52) by George Caleb Bingham.

Rugged frontier explorers such as Daniel Boone, Lewis and Clark, and others loom large in these histories and supposedly testify to the individual spirit and drive of American settlers as they worked to a build a new country out of the “wilderness.” It’s a story designed to inspire pride and confidence in any American about the heritage and spirit of our country.

Except, there’s a lot more to this history than that. Beneath the feel-good, pride-inspiring stories about hardworking Americans building a country out of “nothing,” there is also the story of dispossession and genocide.

Indigenous nations dwelled in those territories and landscapes that American settlers coveted. Overt military force was usually deployed to dispossess these nations of their land.

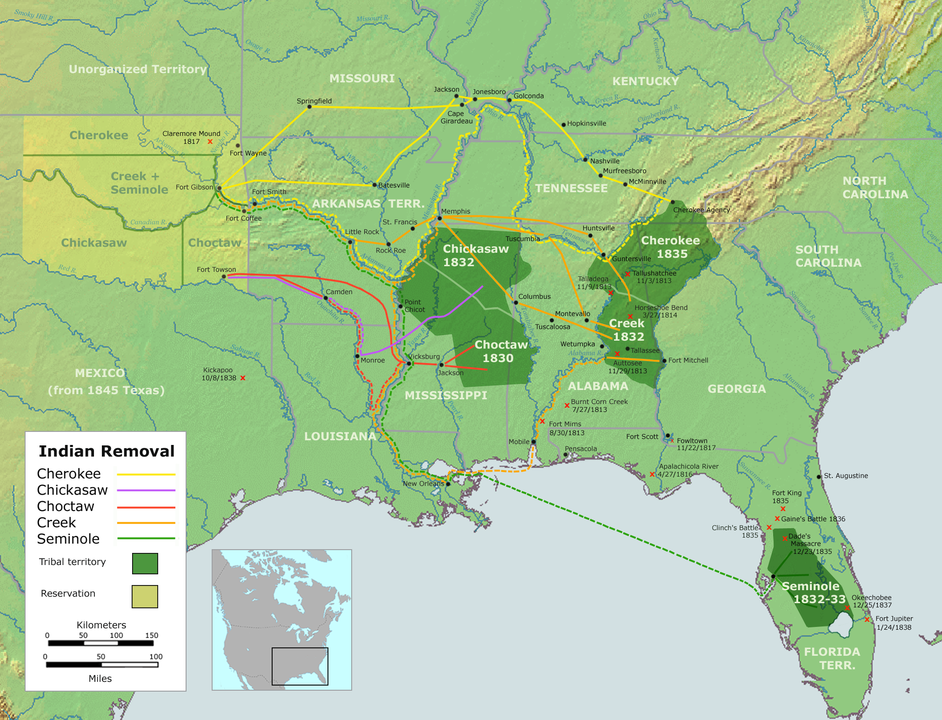

The “Trail of Tears,” which is probably one of the better-known examples of dispossession, was a relocation of tribes in the Southeastern United States westward towards the Mississippi River and eventually into what was known as the “Indian Territory,” now the state of Oklahoma. The land that was stolen became a central part of the plantation economy of the South, worked by slave labor to create wealth for white settler landowners.

These relocations were, of course, just a chapter in a long history of violent dispossessions and seizures of Indigenous land in the United States. The prevailing opinion was that since Indigenous peoples were not using the land in ways that settlers considered “productive,” the land was in far better hands being owned and used by settlers.

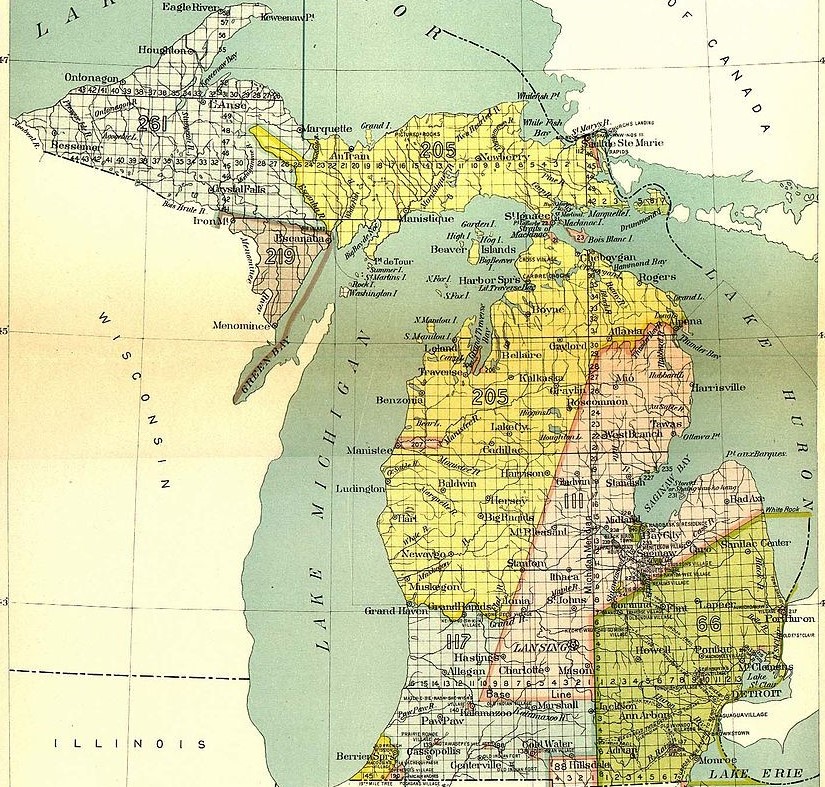

In other cases, land passed into the hands of the United States and settlers through ostensibly “legal” means, via land cession treaties. Under the terms of these treaties, Indigenous tribes agreed to give up lands and relocate to other spaces, or as time went on, to reservations, parcels set aside for them by the U.S. government.

In return for giving up lands, tribes were often guaranteed to retain certain rights in the ceded land, such as hunting, fishing, and gathering rights. The government often promised financial compensation as well in the form of annuity payments to tribes. In theory, this meant that tribes were being well compensated for their land cessions, and the United States gained access to more land for settlement—a win-win scenario.

Except, of course, things very frequently did not work out that way, to the detriment of tribal nations. Treaty rights were infrequently honored or respected, annuity payments were often late or nonexistent, and settler pressures on reservation land led to conflicts.

One notable example of the latter is the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862, a clash overshadowed by the Civil War. In this fight, Dakota peoples in Minnesota had been pushed onto a small reservation in return for promised annuities and other treaty rights. Increased demands for land by Minnesota settlers whittled down the Dakota reservation, and due to the Civil War, annuity payments were usually late if they came at all.

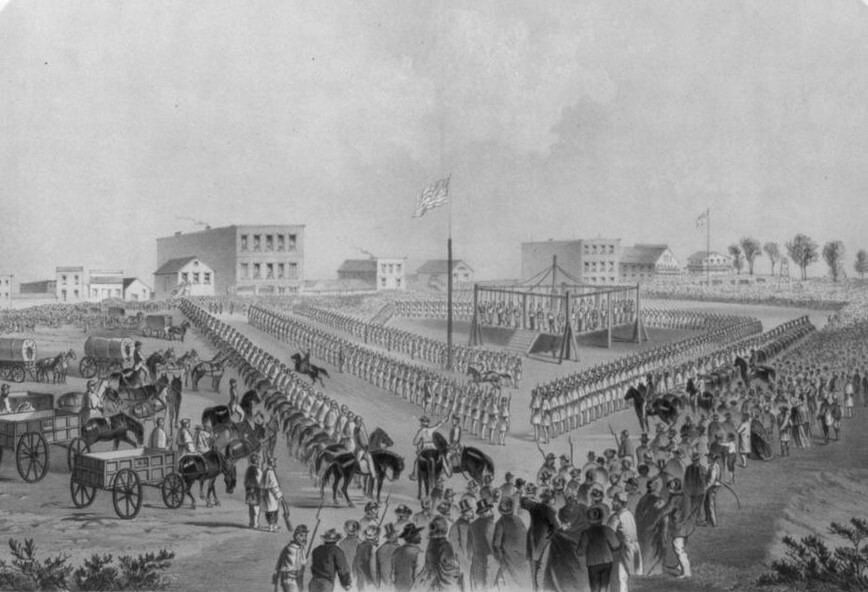

Drawing of the 1862 mass execution in Mankato, Minnesota following the U.S.-Dakota War.

Settler store owners at reservation trading posts were less than sympathetic to the Dakotas’ situation. In this tense atmosphere, a confrontation between some Dakota youth and a settler farmer touched off a bloody clash that ended with the defeat of the Dakota, the loss of their reservation, and the exile of many tribal members westwards out of Minnesota into what we now know as Nebraska and the Dakotas. Thirty-eight Dakota were hanged at Mankato, Minnesota in what is recognized as the largest mass execution in American history.

There are countless other examples of this, of course, including ones that have made their way into popular consciousness.

For example, many Americans are familiar at least with the California Gold Rush, which was far more than a rush of people seeking to make it rich. It also was a time of extreme violence to Indigenous peoples in California. Prospectors and other settlers attacked Indigenous settlements, killing many tribal members. Meanwhile, the process of prospecting itself did widespread ecological damage to waterways and rivers in California and undermined the health of Indigenous communities in the process.

Acts of dispossession often come down to us not as history but as sports nicknames, such as the Gold Rush and the San Francisco 49ers NFL team.

Another example, in 1889 the “Indian Territory,” which had been set aside for tribal nations that had been relocated from the east, was to be opened up for settlement by American settlers. Many settlers who had pushed for the opening of the Territory snuck in early and staked their claims before the land was fully opened to settlement. These people were known as “Boomers” and “Sooners,” names that have come to be associated with the University of Oklahoma, both through its nickname (the Sooners) and its well-known fight song, Boomer Sooner.

The General Allotment Act of 1887, known as the Dawes Act, formalized the reallocation of millions of acres from Indigenous to white control. The Dawes Act divvied up Native land into individual parcels given to Native nuclear families. Anything “left over” was sold off to white settlers and real estate investors. Roughly 100 million acres moved from Indigenous control to settler ownership in the subsequent 50 years.

This is how the West was won. And dispossession was an inherent aspect of many widely celebrated parts of the American past.

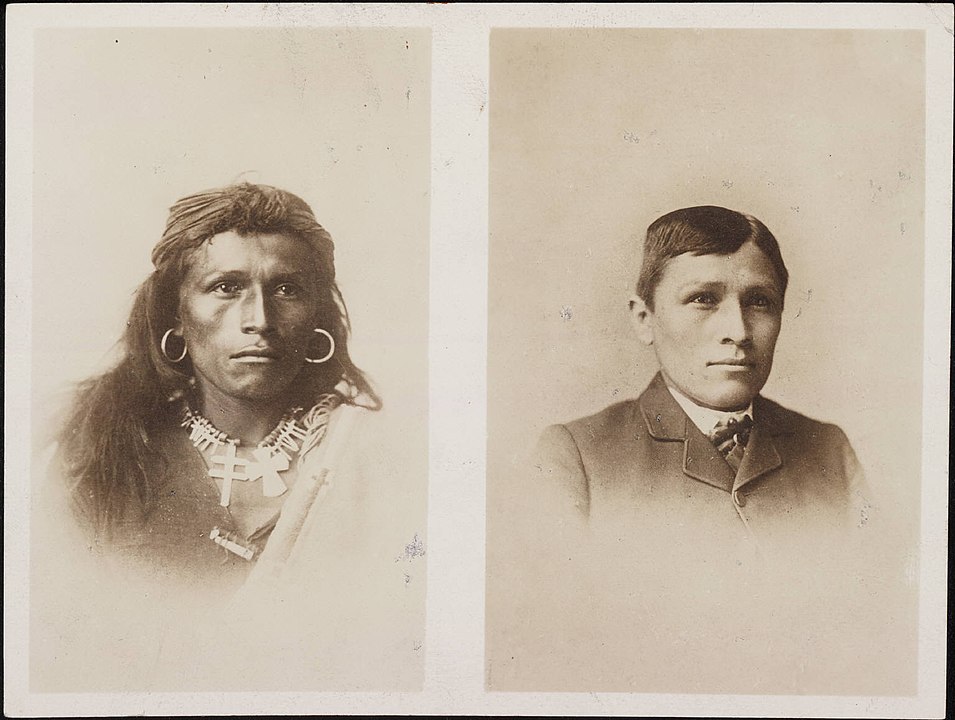

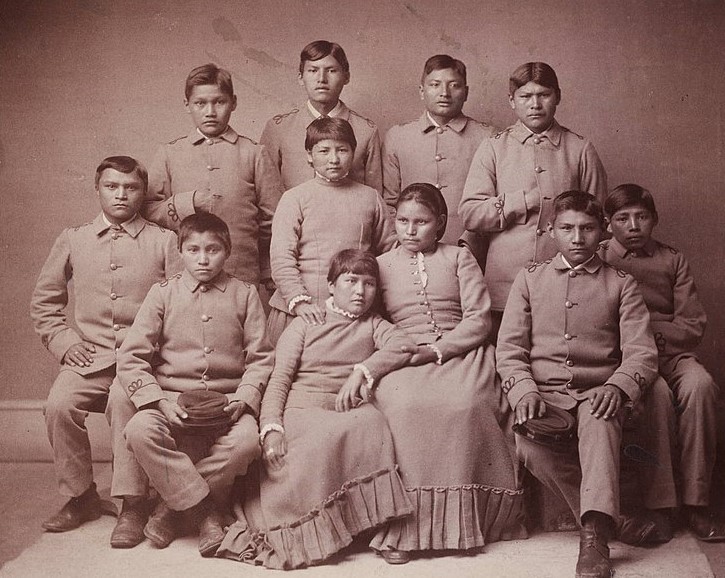

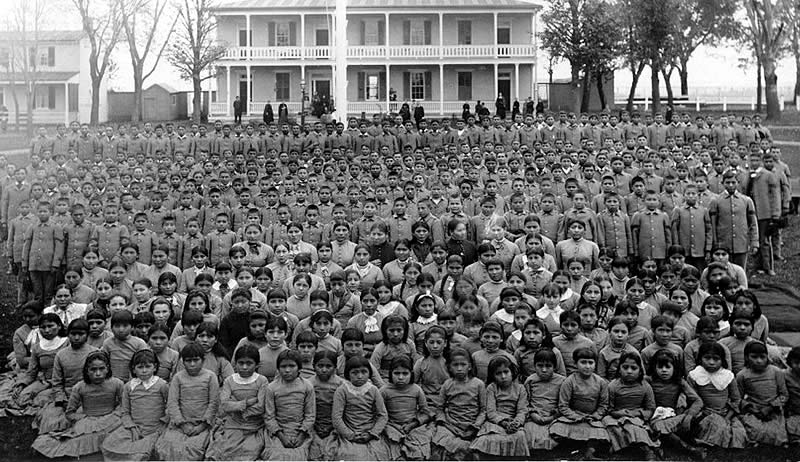

Once the land was taken, the American settler state systematically broke down Indigenous identities. Indigenous children were taken from their families and communities and sent to boarding schools far from their homes, where they were trained to adopt settler customs. They received industrial training designed to help them assimilate into American settler society and take up manual labor roles within the settler economy.

The blood quantum policy, or the idea that the amount of “Indian blood” in an Indigenous person could be determined mathematically, led to situations where individuals could lose their tribal citizenship (and accompanying rights and benefits) because of their parentage.

In the mid-20th century, federal policies of relocation and termination resulted in the removal of recognition and treaty rights from some tribal nations, and pushed tribal members to urban centers, which further eroded tribal communities and identities.

“I mean, yes we have Native Americans…”

As an Ojibwe scholar, teaching Indigenous topics is not new to me—I have been doing it for my entire career. I recently finished teaching a course on Indigenous Environmental Activism, and one of the things that I immediately thought to do was to teach a far more expanded version of the history that I just outlined above.

Some of the most common refrains that I heard from my students as I went through the early part of the semester were, “Wow, I didn’t know that these things happened,” and, “Why didn’t we learn more about Native Americans before this class?” Part of this, I argue, comes from the ways in which this history is taught, or is not taught, in schools, both K-12 and college.

I consider myself fortunate to have learned this history, but I am Indigenous myself, being a citizen of the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe, and I grew up in a state (Minnesota) that has dedicated more attention to Native history and cultures in its educational curricula than other states. (Wisconsin is another notable example of a state that has mandated Indigenous topics in educational curricula.)

The school district I attended had a robust Native educational program—something that I recognize that not every school district has. Even so, when I was able to get access to educational programming from our Native education specialist, Native history was something that we focused once or perhaps twice a year during our social studies classes.

Rather, we learned about the “defining moments” in American history, moments that centered settler perspectives and settler figures. It wasn’t until I got to college that I was able to take a class that focused solely on Indigenous histories and cultures.

Of course, Santorum’s remarks go far beyond just a simple lack of understanding of Native identity. A robust historical accounting quickly reveals that his remarks are just one in a long line of ignorant remarks made by American politicians about Native Americans.

They include George Washington’s statement that “Indians and wolves are both beasts of prey, tho' they differ in shape,” and Thomas Jefferson’s oath, “If ever we are constrained to lift the hatchet against any tribe, we will never lay it down till that tribe is exterminated, or driven beyond the Mississippi.”

And they range from Teddy Roosevelt’s “I don't go so far as to think that the only good Indians are dead Indians, but I believe nine out of ten are, and I shouldn't like to inquire too closely into the case of the tenth,” to Donald Trump’s calling Senator Elizabeth Warren “Pocahontas.”

Even in the cases where Indigenous peoples are mentioned in some of the most commonly known American historical stories, they are positioned as secondary and often are inaccurately described or portrayed.

No matter what has been said, or what has been taught (or not taught), it is clear: For much of this country’s history, Indigenous perspectives and histories have been steadily marginalized and covered up in favor of histories that center on settler colonialism and the ways in which the American settler colony has built itself up.

Individuals such as Squanto, Sacagawea, Pocahontas, and other historic Indigenous figures are portrayed as mere adjuncts to settlers (such as the Pilgrims, the Jamestown colonists, and Lewis & Clark), rather than individuals with agency and motivations of their own, or as part of a larger cultural and political world with its own agendas and struggles.

We often acknowledge that Indigenous peoples did exist, but that recognition is placed in the past tense—tribes are portrayed as having historically once lived in a given space, but then they disappeared. Or their histories trail off, as if they simply stopped existing after a certain point.

Protest against the name and mascot of the Washington Redskins in Minneapolis, 2014.

Not only are we misrepresented by histories, but there is often little attention paid to us in contemporary frameworks. Put bluntly: people forget that Native peoples are still here, and that we have cultural, geographical, and political frameworks that have existed and endured through the history of the United States as well.

The way we tell history and these current views are connected: the writing of Indigenous peoples out of history has led to writing them out of the present as well.

Even in places from which Native peoples were removed, such as Ohio and other places in the Eastern United States, there are thriving and robust communities of Native people in urban centers with their own histories and cultural frameworks.

Many conservative politicians and commentators, like Santorum, have pushed back against what they see as the teaching of “critical race theory” in American classrooms. This label seems to be a catch-all term for any sort of curriculum that brings into question structures of power, privilege, and white supremacy.

Of course, for Indigenous peoples, this is nothing new. Anytime Indigenous peoples in the United States have pushed for a more historically accurate telling of American history in respect to Indigenous nations and communities, they are often met with a variety of responses, none of which are good. The combinations and exact verbal permutations of these responses vary, of course, but these are the sort of “generic” responses that I’ve received in speaking on these topics:

“Why can’t we have pride in our country’s history without being made to feel bad or apologize for being Americans/settlers?”

“Native Americans lost, and histories are written by the victors, so get over it.”

“You already get special treatment/free money/casino money/special rights, so why are you complaining?” (a particularly annoying one to me).

These sorts of responses betray a lack of understanding of the role of Indigenous peoples in American history and show a resistance to learning about these histories.

I argue that if these folks were to learn a bit more about these histories, it not only would chip away at many of the myths that have been built up in the ways that we have constructed American history, but it also would have profound implications for how settler Americans view Indigenous peoples’ roles in contemporary American society.

Viewing Indigenous peoples as vibrant communities with long histories and possessing cultural and political sovereignty that extends to the present day makes it much tougher to view us as caricatures, as insulting sports team mascots or other stereotypical depictions.

It makes it tougher to justify extractive resource production and infrastructure such as mining and pipelines, especially those that run through reservations or even through land ceded by treaty. Just because a space isn’t located within a reservation boundary doesn’t mean that there aren’t ongoing relationships between the land and Indigenous communities.

It calls into question the very nature of how many of the cities, towns, and settlements that make up the United States came to be on the land that they’re on—were they truly created through the hard work and sacrifice of American forefathers and pioneers, as many people including Santorum claim?

Or are these places built upon stolen land, written into histories that erase Indigenous histories and whitewash the violence through which this country was created? And if this is truly the case, what obligations does the United States have to the tribal nations who call these lands home? Could it be that Indigenous political and cultural sovereignty could not only still exist, but do so in a vibrant and resurgent way?

Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne. 2014. An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States. Boston: Beacon Press.

Estes, Nick. 2019. Our History Is the Future: Standing Rock versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance. London: Verso.

Jentz, Paul. 2018. Seven Myths of Native American History. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company.

Rifkin, Mark. 2014. Settler Common Sense: Queerness and Everyday Colonialism in the American Renaissance. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Simpson, Leanne Betasamosake. 2017. As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom Through Radical Resistance. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Wolfe, Patrick. 2006. "Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native." Journal of Genocide Research 8 (4): 387-409.